Acaenasuchus

| Acaenasuchus Temporal range: Late Triassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Life reconstruction by Andrey Atuchin[1] | |

| |

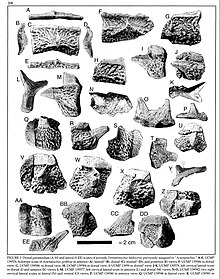

| Holotype scute as seen from five different angles | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Archosauria |

| Clade: | Pseudosuchia |

| Clade: | †Aetosauriformes |

| Genus: | †Acaenasuchus Long & Murry, 1995 |

| Species: | †A. geoffreyi |

| Binomial name | |

| †Acaenasuchus geoffreyi Long & Murry, 1995 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Acaenasuchus (from the Greek akaina, meaning "thorn" and suchus, meaning "crocodile")[2] is an extinct genus of pseudosuchian, endemic to what would be presently be known as Arizona during the Late Triassic, specifically during the Carnian and Norian stages of the Triassic.[3] Acaenasuchus had a stratigraphic range of approximately 11.5 million years.[4] Acaenasuchus is further categorized as one of the type fauna that belong to the Adamanian LVF, based on the fauna of the Blue Mesa Member of the Chinle Petrified Forest Formation of Arizona, where Acaenasuchus was initially discovered.[3]

Discovery and naming

The holotype, UCMP 139576 (a left dorsal paramedian scute), was first discovered by Charles Lewis Camp in 1930.[5] Camp initially named the species "Machaeroprosopus zuni".[3] By 1985, "Machaeroprosopus zuni" was considered a synonym of Desmatosuchus, and was reclassified as a juvenile Desmatosuchus by Robert A. Long and Karen Ballew in 1985.[6] UCMP 139576 was eventually moved into its own taxon and classified under the name Acaenasuchus, upon reclassification by Robert A. Long and Philip A. Murry in 1995.[2] Fun Fact! The species epithet Acaenasuchus geoffreyi was named after Geoffrey Long, Robert A. Long's son, for his "considerable patience while his father was away in the field".[2] Long and Murry are credited for providing the most stable evidence that Acaenasuchus was an independent taxon. Long and Murry identified small dorsal plates along the carapace of Acaenasuchus, and identified what they described to be"ornithischian-like" teeth, in addition to a multitude of other proposed synapomorphies.[2] Some of which are the subjects of active studies regarding Acaenasuchus characterization.[3]

The holotype UCMP 139576 was discovered in the Petrified Forest Member of the Chinle Formation and belongs to a fully grown individual,[2] as opposed to a juvenile as initially believed. The Upper Triassic Chinle Formation of Arizona is abundant with fossils belonging to over 18 different taxa groups.[7] Collections from the 1890s onwards document various holotypes of these ranging taxa, including that of Acaenasuchus.[3]

In addition to the holotype UCMP 139576, 95 other scutes under 90 catalogue numbers likely also belong to Acaenasuchus.[2][6] Another specimen, known as SMU 75403, was described by Marsh et al. (2020), and consists of representative cranial, vertebral, and appendicular elements as well as previously unknown variations in the dorsal carapace and ventral shield.[8]

Validity of the taxon

The classification of Acaenasuchus as an independent taxon has been the topic of controversy due to its similarities to Desmatosuchus. Upon review by Andrew B. Heckert and Spencer G. Lucas, the characters that Long and Murry claim to distinguish between the two species may not represent novel scute features but rather ontogenetic variation.[6] These characters include pitting over the dorsal scutes of Acaenasuchus and division between the raised boss into two flanges of Acaenasuchus, neither of which are present in Desmatosuchus.[3] Heckert and Lucas argue that the visible pits and grooves over the dorsal scutes of Acaenasuchus indicate a juvenile stage of Desmatosuchus development. They elaborate that this pitting is a developmental ontogenetic feature that has been observed in the maturation process of other Aetosaurs, specifically in the taxa Aetosaurus.[3]

In addition to the ontogenetic variation hypothesis, Heckert and Lucas have determined that of the four locations within the Adamanian LVF where Acaenasuchus holotypes have been excavated, two localities are a site of great abundance of adult Desmatosuchus fossils.[6]

While studies are ongoing, the majority of working paleontologists agree that Acaenasuchus should retain its status as a valid taxon, independent of Desmatosuchus. The "pitting" as an example of ontogenetic developments is not supported strongly... due to the fact that the concept of ontogenetic maturation is a poorly understood phenomena within Aetosauria.[3] To address the geographical proximity of Acaenasuchus fossils to those of adult Desmatosuchus, evidence has not been studied to an extent sufficient to claim synonymy at this time. There are too many variables to consider, such as the possibility that both species lived in close proximity to each other during the Late Triassic period. It is also notable that the Chinle Formation is a region rich in Aetosaur specimens, not solely Desmatosuchus.

Description

Acaenasuchus was very small and narrow-bodied.[8] It is hypothesized to be less than 0.6 m (2 ft 0 in) in length. Long and Murry provided the characterization of multiple Acaenasuchus features upon its discovery in 1995.[2] Acaenasuchus possess paramedian scutes with anterior laminae, similar to Desmatosuchus. However, Acaenasuchus is characterized specifically by scutes highly developed through the pre-sacral series.[2] These scutes further include the presence of thornlike processes parallel along the side of the posterior region of the paramedian scutes.[2] Additionally the scutes are described as highly ornamented with ridges and hollows not present in Desmatosuchus.[8] It was known only by its dermal armor until 2016. The 2016 excavations revealed cranial, mandibular, vertebral, pelvic, etc... bones.[9][2]

Paramedian scutes

Acaenasuchus paramedian scutes are relatively small in size, similar to the putative size of the taxa itself.[4] They have decreased transverse angulation and include a transverse furrow on the dorsal face. Acaenasuchus paramedian scutes do not include the "tongue in groove" articulation with adjacent plates as seen on Desmatosuchus.[2] Medial and lateral "wing" structures emanate from the ridges of the pre-sacral scutes.[2] Deeply incised pitting is visualized posterior to the pre-sacral scutes.[2] A division of the raised boss is also noted. [3]The raised boss is absent on cervical paramedian scutes only.[6]

Lateral scutes

In addition to paramedian scute identification, lateral scutes have been similarly described on Acaenasuchus. Lateral scutes are features unique to Aetosaurids.[10] The lateral scutes are longer than they are wide in Acaenasuchus. They have increased angulation when compared to the paramedian scutes, suggesting heavy armor on the dorsal surface when compared to the lateral surface.[2] There are two types of "horn" structures observed on the lateral scutes. Conical horns curved dorsally, laterally, and posteriorly… and were wider than the scutes themselves.[2] Conical horns typically displayed ornamentation such as furrows. Blunt horns showed less curvature and did not include ornamentation. Acaenasucus lateral scutes' lack anterior bars but possess anterior laminae.[6]

Cranium/mandible

There is ornamentation on the lateral side of the maxilla in the form of grooves below the ant-orbital foramen, and ridges and pits above.[9] There is a short anterior process of the maxilla which projects ventrally.[9] The teeth are described as having a rounded tip similar to R. callenderi, and contain broad denticles.[9]

There is ornamentation on the lateral surface of the jugal bone in the form of ridges and pits.[9] The bone is thin and tapers in the posterior direction.[9] An early suchian feature, there is a sharp longitudinal ridge present on the lateral side of the jugal.[7] In Acaenasuchus, the longitudinal ridge lies above a shallow groove.[9]

The frontal bone of Acaenasuchus is relatively narrower in the anterior direction. There is ornamentation on the dorsal surface of the frontal bone in the form of sharp circular ridges and oblong pits.[9] There is a large boss that forms the dorsal surface of the orbit, perhaps representing a palpebral co-ossification to the frontal.[9] There are two foramina present on the ventral surface of the bone beneath the large boss.[9]

The parietal bone is ornamented with sharp ridges and deep pits on the dorsal surface.[9] The dorsal surface of the parietal bone lacks a midline crest.[9]

The squamosal bone of Acaenasuchus is longer anteriorly than it is wide posteriorly. The dorsal surface of the squamosal is ornamented in the form of small ridges and pits.[9] The articular facet is broad.

The surangular articulates the articular. The lateral side of the surangular is ornamented in the form of long ridges and oblong pits.[9] The medial articular foramen is present.[9] The retro-articular process of Acaenasuchus is short and curved.[9]

Vertebral column

Trunk vertebrae are the only non-sacral vertebrae identified on Acaenasuchus thus far. Each is similar in size and includes centrum, neural arches, zygapophyses, and transverse processes. The centrum is amphicoelous, and includes longitudinal depressions on the lateral surfaces just below the neural arch.[9] The neural arch is flat, similar to E. olseni, and dorsoventrally short.[9] The most distal end of the transverse process includes ornamentation in the form of small pits and grooves.[9] The zygapophyses are situated close to each other along the midline of each trunk vertebrae.[9] Sacral vertebrae identified in Acaenasuchus have been reconstructed from fragments of sacral ribs, sacral centra, and sacral vertebra.[9] The centrum is amphicoelous and short much like the trunk vertebrae. The sacral rib is found on the anterior side of the centrum. The neural arch is short. The zygapophyses are separated by a thin slot.[9]

Pectoral girdle

The scapula of Acaenasuchus has not been fully excavated, only the proximal portion of the scapula has been recovered. The articulation with the coracoid has been observed. There is a small tubercle present above the glenoid towards the posterior end of the scapula.[9]

The coracoid has only been partially excavated as well. The proximal end of the coracoid including articulation with the scapula has been described.[9]

The humerus has been recovered including all regions but the mid-diaphysis. Three bulb like structures can be observed on the humeral head.[9] The median humeral head is the largest of the three. A semicircular foramen is observed underneath the humeral head. A sub-circular "cuboid fossa" is described on the distal portion of the humerus.[9]

Pelvic girdle

The ilium is vertically oriented in Acaenasuchus. The lateral surface of the ilium does not have a second crest above the supra-acetabular crest but does have a tubercle between the supra-acetabular crest and the pre-acetabular process.[9] The pre-acetabular process is short and faces anteriorly. Two rib attachment scars are observed on the medial side of the ilium. These scars indicate articulations with two sacral vertebrae.[9] The iliac and ischiadic pedicles are not perforated in Acaenasuchus as they are in dinosauriformes.[9] The obturator foramen perforates the pubis.

The femur is relatively short and solid. The femoral head is "blocky" and includes a short groove on the proximal surface.[9] On the anterior surface, the distal region of the femur is smooth.[9]

Paleobiology

The carapace of Acaenasuchus is of normal proportions, with most armor including thin anterior laminae. Multiple plates of the carapace include extensive laminae suggesting that the carapace was highly flexible, allowing Acaenasuchus to move swiftly with agility.[2] Caudal armor and pectoral spikes are lost in Acaenasuchus when compared to Desmatosuchus, further suggesting an evolutionary tradeoff between defense and armor in exchange for speed and agility.[8]

Paleoecology

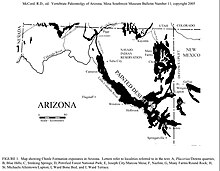

Most excavations of vertebrate fossils from the Chinle Formation occurred over floodplains, bogs, small ponds, and near other fluvial channels.[7] Sandstone deposits represent channel systems flowing throughout the area, gleyed mudstones represent floodplain paleosols, and organic mudstones represent bogs.[7] Acaenasuchus was known to be a terrestrial organism, there is little information available that would suggest the Acaenasuchus had semiaquatic potential.[11] Chinle climates in the Late Triassic, when Acaenasuchus lived, is hypothesized to have had significant precipitation seasonally. There may have been what we would categorize today as a dry and wet season. The Chinle Formation during the Late Triassic was a time and place of great faunal diversity. Archosaurs were evolving and diversifying rapidly, Acaenasuchus is hypothesized to occupy a similar niche to smaller archosaurs of the time.[7]

Taxonomy

Acaenasuchus has been organized under the clade Pseudosuchia, the crocodilian line archosaurs. Acaenasuchus is further organized within the order Aetosauria[6] which is recognized by the presence of a carapace indicated by paramedian and lateral scutes. The carapace is composed of two columns of each dorsal and lateral scutes which have the capacity to vary extensively between individual Aetosaurids.

Acaenasuchus was assigned to the family Stagonolepididae by Irmis (2005).[12] Stagonolepididae is the subfamily of Aetosauria and is described by the following synapomorphies: the presence of a deep fontanelle at the base of the basisphenoid, and the absence of a raised boss, specifically over the cervical paramedian scutes.[13]

In 2020, a phylogenetic analysis found Acaenasuchus to be closely related to Revueltosaurus and Euscolosuchus.[8] Ongoing research classifies A. geoffreyi with other specimens' E. olseni and R. callendri as sister taxa to the group Aetosaurids, rather than a part of the group. This led to the study concluding that Acaenasuchus should be classified under the more broad clade of Aetosauroformes, due to the lateral osteoderms found on their carapace.[14]

References

- ^ New geosciences study shows Triassic fossils that reveal origins of living amphibians. Virginia Tech. Live reconstruction of Funcusvermis gilmorei and A. geoffreyi

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p R. A. Long and P. A. Murry. (1995). Late Triassic (Carnian and Norian) tetrapods from the southwestern United States. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 4:1-254

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Parker, W. G.; McCord, R. D. (2005). "Faunal review of the Upper Triassic Chinle Formation of Arizona. Mesa Southwest" (PDF). Mesa Southwest Museum Bulletin. 1 (11): 34–54.

- ^ a b Paleobiology Database: Acaenasuchus, basic info

- ^ Camp, C. L., (1930), A study of the phytosaurs with description of new material from western North America: Memoirs of the University of California, v. 19, 174 p.

- ^ a b c d e f g Heckert, A.B. and Lucas, S. G. (2002). Acaenasuchus geoffreyi (Archosauria: Aetosauria) from the Upper Triassic Chinle Group: Juvenile of Desmatosuchus haplocerus. Upper Triassic Stratigraphy and Paleontology. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin No. 21.

- ^ a b c d e Michael Parrish, J. (1989-01-01). "Vertebrate paleoecology of the Chinle formation (Late Triassic) of the Southwestern United States". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. XIIth INQUA Congress. 72: 227–247. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(89)90144-2. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ a b c d e Marsh, Adam D.; Smith, Matthew E.; Parker, William G.; Irmis, Randall B.; Kligman, Ben T. (2020-10-12). "Skeletal Anatomy of Acaenasuchus Geoffreyi Long and Murry, 1995 (Archosauria: Pseudosuchia) and its Implications for the Origin of the Aetosaurian Carapace". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 40 (4): e1794885. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1794885. hdl:10919/102375. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Marsh, Adam D.; Smith, Matthew E.; Parker, William G.; Irmis, Randall B.; Kligman, Ben T. (2020-07-03). "Skeletal Anatomy of Acaenasuchus Geoffreyi Long and Murry, 1995 (Archosauria: Pseudosuchia) and its Implications for the Origin of the Aetosaurian Carapace". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 40 (4): e1794885. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1794885. hdl:10919/102375. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Roberto De Silva, L.; Desojo, J.B.; Cabreira, S.F.; Aires, A.S; Mueller, R.T.; Pacheco, C.P.; Dias Da Silva, S. (2014). "A new aetosaur from the Upper Triassic of the Santa Maria Formation, southern Brazil". Zootaxa. 3764 (3): 240–278.

- ^ Parker, William G. (2010-03-09). "Reassessment of the Aetosaur 'Desmatosuchus' chamaensis with a reanalysis of the phylogeny of the Aetosauria (Archosauria: Pseudosuchia)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. doi:10.1017/S1477201906001994.

- ^ R. B. Irmis. (2005). The vertebrate fauna of the Upper Triassic Chinle Formation in northern Arizona. In S. J. Nesbitt, W. G. Parker, & R. B. Irmis (eds.), Guidebook to the Triassic Formations of the Colorado Plateau in Northern Arizona: Geology, Paleontology, and History. Mesa Southwest Museum Bulletin 9:63-88

- ^ Heckert, A. B.; Lucas, S. G. (2000). "Taxonomy, phylogeny, biostratigraphy" (PDF). Biochronology, Paleobiogeography. 1 (1): 5–10.

- ^ Parker, William G.; Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Irmis, Randall B.; Martz, Jeffrey W.; Marsh, Adam D.; Brown, Matthew A.; Stocker, Michelle R.; Werning, Sarah (October 2022). "Osteology and relationships of Revueltosaurus callenderi (Archosauria: Suchia) from the Upper Triassic (Norian) Chinle Formation of Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona, United States". The Anatomical Record. 305 (10): 2353–2414. doi:10.1002/ar.24757. ISSN 1932-8486. PMC 9544919. PMID 34585850.