Abraham Hayyim Adadi

Abraham Hayyim Adadi | |

|---|---|

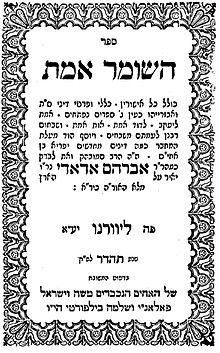

Title page of HaShomer Emet by Hakham Abraham Hayyim Adadi | |

| Personal life | |

| Born | Abraham Hayyim Adadi 1801 |

| Died | June 13, 1874 (aged 72–73) |

| Children | Saul Adadi |

| Parent | Mas'ud Hai Adadi |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Judaism |

Abraham Hayyim Adadi (Hebrew: אברהם חיים אדאדי, 1801 – June 13, 1874)[1] was a Sephardi Hakham, dayan (rabbinical court judge), av beit din (head of the rabbinical court), and senior rabbi of the 19th-century Jewish community of Tripoli, Libya. In his younger years, he lived in Safed, Palestine, and traveled to Jewish communities in the Middle East and North Africa as a shadar (rabbinical emissary) to raise funds for the Safed community. He returned to Safed a few years before his death and was buried there. He published several halakhic works and also recorded the local minhagim (customs) of Tripoli and Safed, providing a valuable resource for scholars and historians.[2]

Biography

Abraham Hayyim Adadi was born in Tripoli to Mas'ud Hai Adadi, the son of Hakham Nathan Adadi.[3] Nathan Adadi was originally from Palestine;[2] he came to Tripoli as a shadar (rabbinical emissary) and stayed to learn under Hakham Mas'ud Hai Rakkah, one of the leading rabbis of Libyan Jewry in the 18th century.[2][4] He married his teacher's daughter[5] and had one son, Mas'ud Hai Adadi. Abraham Hayyim was orphaned of both his parents at a young age and was raised by his grandfather.[1][3][6]

In 1818 Adadi accompanied his grandfather to Palestine, where they settled in Safed.[1] His grandfather died that same year.[1] The 18-year-old Abraham Hayyim enrolled in the yeshiva of Rabbi Yosef Karo, received rabbinic ordination, and studied to become a dayan (rabbinical court judge).[1]

In 1830 he was appointed as a shadar to raise funds on behalf of the Safed Jewish community. He traveled to Jewish communities in Syria, Iraq, Persia, Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, and Livorno, Italy.[1][6] He was in Livorno at the time of the devastating Safed earthquake of 1837, and decided to return to his native Tripoli.[6] He served the Tripoli Jewish community as a rav, dayan, av beit din, and rosh yeshiva over the next 30 years.[1][6][7] He was regarded as the senior rabbi in Tripoli.[2][6]

Adadi paid special attention to the education of children of Torah scholars and children of the poor. Together with other rabbis, he signed a takkanah calling for each member of the community to contribute 3/1,000th of their income toward youth education.[8] He also appointed a special overseer for the needs of the poor, and levied a 5 percent tax on local merchants to pay for teachers for poor children.[1][6]

In 1862 Adadi published the second volume of his great-grandfather Mas'ud Hai Rakkaḥ's halakhic work, Ma'aseh Rokeaḥ.[9] His cousin and contemporary, Hakham Jacob Rakkah, a great-great-grandson of Mas'ud Hai Rakkaḥ, published the third volume of Ma'aseh Rokeaḥ in 1863.[9]

In 1870, at the age of 70, Adadi returned to Safed with his wife, while his son, Saul, remained in Tripoli.[6] Adadi died in Safed on Shabbat, June 13, 1874 (28 Sivan 5634), and was buried in the rabbinical section of the Safed cemetery.[1]

Works

Adadi was recognized as an expert in Talmud study, displaying an understanding of both the text and the historical differences between the writings of the Tannaim and Amoraim.[8] He also recorded the history and minhagim (customs) of the Jewish communities of Tripoli and Safed in his books, providing a valuable resource for scholars and historians.[1][3][10][11][12] In his first work, HaShomer Emet (1849), he included a poem that he had written in praise of the city of Safed.[3][13]

His main works are:

- HaShomer Emet (The True Guardian), on the laws and customs of writing a Torah scroll. Published 1849 in Livorno,[3] reprinted together with Vayikra Avraham in 1992 in Brooklyn, New York.[8]

- Vayikra Avraham (And Abraham Called), responsa on the four sections of the Shulchan Aruch. Published 1865 in Livorno,[3] reprinted 1983 in Jerusalem.[14] Appendices in this work include Sdeh Migrash on divorce and Yosef Amar, a description of Libyan Jewish customs.[1]

His handwritten manuscripts containing Talmudic novellae and drashot (sermons) are preserved at the Yad Ben Zvi institute in Jerusalem.[3]

Rakkah-Adadi family tree

| Aharon Rakkah | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mas'ud Hai Rakkah | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yitzhak Rakkah | Nathan Adadi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Baruh Rakkah | Mas'ud Hai Adadi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shilomo Rakkah | Abraham Hayyim Adadi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jacob Rakkah | Zion Rakkah | Saul Adadi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Abraham Rakkah | Meir Rakkah | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "חכם אברהם חיים אדאדי" [Hakham Abraham Hayyim Adadi] (in Hebrew). HeHakham HaYomi. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d Hirschberg 1981, p. 179.

- ^ a b c d e f g Skolnik & Berenbaum 2007, p. 370.

- ^ Hallamish 2001, p. 78.

- ^ Nissim 1964, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g "ר' אברהם חיים אדאדי זצוק"ל" [Rabbi Abraham Hayyim Adadi]. Or-Shalom. 26 January 2004. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ Ghian, David; Ghian, Yosef (August 2009). "משפחת רבה: קורות המשפחה בלוב" [A Great Family: Chronicles of the family in Libya] (PDF). לבלוב 6 (in Hebrew). World Organization of Libyan Jews: 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-09-05.

- ^ a b c Berlin 2011, p. 16.

- ^ a b "Ma'aseh Rokeaḥ" (in Hebrew). hebrewbooks.org. 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ Farber, Zev (January 2008). "Women, Funerals, and Cemeteries". Jofa Journal. academia.edu. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ Zoartz, Freija (1967). "ממנהגי יהדות לוב" [Customs of Libyan Jewry] (in Hebrew). Hertzog College. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ Goldberg 1993, p. 17.

- ^ "HaShomer Emet. Leghorn, [1849]. First Edition". Live Auctioneers. 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ אדאדי, אברהם חיים (1983). שאלות ותשובות ויקרא אברהם [Vayikra Avraham Responsa].

Sources

- Berlin, Adele, ed. (2011). The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199730049.

- Goldberg, Harvey E., ed. (1993). The Book of Mordechai: A Study of the Jews of Libya. Darf Publishers. ISBN 9781850772309.

- Hallamish, Moshe (2001). הקבלה בצפון אפריקה למן המאה הט"ז : סקירה היסטורית ותרבותית [The Kabbalah in North Africa: A Historical and Cultural Survey] (in Hebrew). Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameyuchad.

- Hirschberg, H. Z. (1981). A History of the Jews in North Africa: From the Ottoman conquests to the present time. Vol. II. Brill. ISBN 9004062955.

- Nissim, Yitzhak (1964), "Introduction" (PDF), Ma'aseh Rokeaḥ (in Hebrew), vol. IV

- Skolnik, Fred; Berenbaum, Michael, eds. (2007). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 1. Granite Hill Publishers. ISBN 978-0028659299.

External links

- HaShomer Emet at Hebrewbooks.org

- Vayikra Avraham at Hebrewbooks.org