8th Division (Australia)

| 8th Division | |

|---|---|

Members of 'C' Company, 2/30th Battalion disembark at Singapore, from Johan Van Oldenbarnevelt (HMT FF), part of Convoy US11B, 15 August 1941. | |

| Active | 1940–1942 |

| Disbanded | Ceased to exist in 1942 after majority of division were captured as prisoners of war. |

| Country | Commonwealth of Australia |

| Branch | Australian Army |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | ~ 20,000 all ranks |

| Part of | Second Australian Imperial Force |

| Engagements | World War II |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Gordon Bennett |

| Insignia | |

| Unit colour patch |  |

The 8th Division was an infantry division of the Australian Army, formed during World War II as part of the all-volunteer Second Australian Imperial Force. The 8th Division was raised from volunteers for overseas service from July 1940 onwards. Consisting of three infantry brigades, the intention had been to deploy the division to the Middle East to join the other Australian divisions, but as war with Japan loomed in 1941, the division was divided into four separate forces, which were deployed in different parts of the Asia-Pacific region. All of these formations were destroyed as fighting forces by the end of February 1942 during the fighting for Singapore, and in Rabaul, Ambon, and Timor. Most members of the division became prisoners of war, waiting until the war ended in late 1945 to be liberated. One in three died in captivity.

History

Formation

The 8th Division began forming in July 1940, with its headquarters being established at Victoria Barracks, in Sydney. The division's first commander was Major General Vernon Sturdee. The third division raised as part of the all-volunteer Second Australian Imperial Force, the formation was raised amidst an influx of fresh volunteers for overseas service following Allied reverses in Europe.[1] Consisting of around 20,000 personnel, its principal elements were three infantry brigades, with various supporting elements including a machine gun battalion, an anti-tank regiment, a divisional cavalry regiment, and engineer, signals and other logistic support units. Each infantry brigade also had an artillery regiment assigned.[2]

The three infantry brigades assigned to the division were the 22nd, 23rd and 24th. These were raised in separate locations: the 22nd (Brigadier Harold Taylor) in New South Wales, the 23rd (Brigader Edmund Lind) in Victoria and Tasmania and the 24th (Brigader Eric Plant) in the less populous states of Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia.[1] In September 1940, a reorganisation of the 2nd AIF resulted in the 24th Brigade being sent to North Africa, where it became part of the 9th Division. It was replaced in the 8th Division by the 27th Brigade (Brigadier Duncan Maxwell), which was the last 2nd AIF brigade to be formed.[3] The division's cavalry regiment was also transferred to the 9th Division.[4]

While it had initially been planned for the 8th Division to deploy to the Middle East, as the possibility of war with Japan loomed, the 22nd Brigade was sent instead to Malaya on 2 February 1941 to undertake garrison duties there following a British request for more troops. This was initially a temporary move, with plans for the brigade to rejoin the division, which would then be transferred to the Middle East.[5] Meanwhile, the 23rd Brigade moved to Darwin in April 1941. The 2/22nd Battalion was detached from it and deployed to Rabaul, New Britain that month, as part of plans to deploy to the islands to Australia's north in the event of war with Japan; ill-prepared, poorly equipped and hastily deployed, they would ultimately be destroyed. The 27th Brigade joined the 22nd Brigade in Malaya, in August. The remainder of the 23rd Brigade was split into another two detachments: the 2/40th Battalion to Timor, while the 2/21st Battalion went to Ambon in the Dutch East Indies.[6][7] In October 1941, the 23rd Brigade officially taken off the division's order of battle, to simplify command arrangements, which had been strained by the splitting of the division's brigades.[8]

Malaya

As war broke out in the Pacific Japanese forces based in Vichy French-controlled Indochina quickly overran Thailand and invaded Malaya. The loss of two British capital ships, HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales, off Malaya on 10 December 1941, neutralised Allied naval superiority,[9] allowing the Japanese to perform amphibious assaults on the Malayan coast with much less resistance. Japanese forces met stiff resistance from III Corps of the Indian Army and British units in northern Malaya, but Japan's superiority in air power,[10] tanks and infantry tactics forced the British and Indian units, who had very few tanks and remained vulnerable to isolation and encirclement,[11][12] back along the west coast towards Gemas and on the east coast towards Endau.[13]

On 14 January 1942, parts of the division went into action for the first time south of Kuala Lumpur, at Gemas and Muar. The 2/30th Battalion had some early success at the Gemencheh River Bridge, carrying out a large-scale ambush which destroyed a Japanese battalion.[14] Following this, the Japanese attempted a flanking towards Muar. The 2/29th and the 2/19th Battalions were detached as reinforcements for the 45th Indian Infantry Brigade, which was in danger of being overrun near the Muar River. By 22 January, a mixed force from the two battalions, with some Indian troops, had been isolated and forced to fight their way south to Yong Peng. Members of the Imperial Japanese Guards Division massacred about 135 Allied prisoners at Parit Sulong, following the fighting. Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Anderson, acting commander of the 2/19th, was later awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions in leading the break out.[15]

On the east coast, the 22nd Brigade fought a series of delaying actions around Mersing, as the Japanese advanced. On 26 January, the 2/18th Battalion launched an ambush around the Nithsdale and Joo Lye rubber plantations, which resulted in heavy Japanese casualties and briefly held up their advance allowing the 22nd Brigade time to withdraw south.[16] Meanwhile, the remainder of the 27th Brigade waged a rearguard action around the Ayer Hitam trunk road,[17] while the 22nd Brigade was sent back to guard the north end of the Johore–Singapore Causeway which linked the Malayan Peninisula to Singapore, as Allied forces retreated.[18]

Singapore

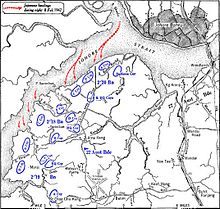

As Allied forces in Malaya retreated towards Singapore, a 2,000-strong detachment of 8th Division reinforcements arrived in Singapore, including the 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion. These reinforcements were largely provided to the 2/19th and 2/29th Battalions which had suffered heavy casualties in Malaya, although most had not completed basic training and they were ill-prepared for the fighting to come. By 31 January, the last British Commonwealth forces had left Malaya, and engineers blew a hole 70 feet (21 m) wide in the causeway.[19] The Allied commander, Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival, gave Major General Gordon Bennett's 8th Division the task of defending the prime invasion points on the north side of the island, in a terrain dominated by mangrove swamps and forest.[20] The 22nd Brigade was assigned a daunting 10-mile (16 km) wide sector in the west of the island amidst a tangle of islets and mangrove swamps, and the 27th Brigade a 4,000-yard (3,700 m) zone in the north-west, near the causeway.[21] From vantage points across the straits, including the Sultan of Johore's palace, as well as aerial reconnaissance and infiltrators, the Japanese commander, General Tomoyuki Yamashita and his staff gained an excellent knowledge of the Allied positions. From 3 February, the Australian positions were shelled by Japanese artillery.[22] Shelling and air attacks intensified over the next five days, destroying communications between Allied units and their commanders.[23]

At 8.30 pm on 8 February, Australian machine gunners opened fire on vessels carrying a first wave of 16 infantry battalions, totalling around 4,000 Japanese troops, towards Singapore Island, concentrating on the positions occupied by the 3,000-strong 22nd Brigade.[24] While the artillery fired thousands of rounds in response to support calls, confused and desperate fighting raged throughout the evening. Eventually the increasing Japanese numbers, poor siting of defensive positions, and lack of effective communications, allowed Japanese forces to exploit gaps in the Australian lines. By midnight the two 8th Division infantry brigades, the 22nd and 27th, were separated and isolated, and the 22nd had begun withdrawing towards Tengah.[25] By 1:00 am, further Japanese troops – bringing the total to 13,000[26] – had begun landing and as the main Australian force was pushed back towards Tengah airfield, small groups of troops that had been bypassed by the Japanese fought to rejoin their units as they had withdrawn toward Tengah airfield.[27] Around dawn on 9 February a further 10,000 Japanese troops landed,[26] and as it became clear that the 22nd Brigade was being overrun and it was decided to form a secondary defensive line to the east of Tengah airfield and north of Jurong.[28]

The 27th Brigade had not yet faced an attack. However, the next day, the Japanese Imperial Guard made a botched landing in the northwest, suffering severe casualties from drowning and burning oil in the water, as well as Australian mortars and machine guns.[29] In spite of the 27th Brigade's success, as a result of a misunderstanding between Brigadier Duncan Maxwell and Bennett, they began to withdraw from Kranji in the north.[30] That same day, communication problems and misunderstandings, led to the withdrawal of two Indian brigades, and loss of the crucial Kranji–Jurong ridge through the western side of the island.[31]

The Australian battalions attempted several local counterattacks as they attempted to shore up their lines. One such attack, saw the Bren carriers of the 2/18th Battalion conduct a mobile ambush.[32][33] Nevertheless, the British Commonwealth forces steadily lost more ground, with Japanese penetrating to within five miles of Singapore urban centre, by 10 February capturing Bukit Timah. On 11 February, knowing that his own supplies were running low, Yamashita called on Percival to "give up this meaningless and desperate resistance".[34] The next day the Allied lines attempted to stabilise along the Krangi–Jurong line on west side of the island, with an ad hoc battalion of Australian reinforcements being committed to hasty counterattack. This was eventually cancelled, but the battalion was not recalled, and it was later set upon by the Japanese 18th Division as the Japanese recommenced offensive actions.[35] Meanwhile, the 27th Brigade attempted to retake Bukit Timah, but the attack was repulsed by stubborn defence from Japanese Imperial Guards troops.[36]

On 13 February, Bennett and other senior Australian officers advised Percival to surrender, in the interests of minimising civilian casualties. Percival refused but unsuccessfully sought authority to surrender from his superiors.[37] The following day the remaining British Commonwealth units battled on. The Australians established a defensive perimeter to the north-west of the city centre around Tanglin Barracks, while preparations were made to mount a final stand.[38] Meanwhile, civilian casualties mounted as civilians crowded into the area now held by the Allies and bombing and artillery attacks intensified. Civilian authorities began to fear that the water supply would soon give out.[39] Japanese troops killed 200 staff and patients after they captured Alexandra Barracks Hospital.[40]

By the morning of 15 February, the Japanese had broken through the last line of defence in the north and food and some kinds of ammunition had begun to run out. After meeting his unit commanders, Percival contacted the Japanese and formally surrendered the Allied forces to Yamashita, shortly after 5:15–pm. Bennett created an enduring controversy when he handed over the 8th Division to the divisional artillery commander, Brigadier Cecil Callaghan, commandeered a boat and managed to escape captivity.[41] According to Frank Owen, his lack of inspired leadership was exemplified by one of his last orders: because of lack of ammunition he issued orders that Australian gunners were only to offer artillery support in their own sector. He did not inform Percival of this order.[42]

In the aftermath, almost 15,000 Australians became prisoners of war at Singapore, an absolute majority of all Australian prisoners of the Japanese in World War II. Due to Japanese mistreatment and neglect, many died in the prisoner of war camps, and around 2,400 Australian prisoners died in the Sandakan Death Marches.[43] A small number were able to escape POW camps and continue fighting either by making their way back to Australia,[44] or as members of guerrilla units (for example Jock McLaren).[45]

Analysis of the 8th Division's performance in Malaya and Singapore has been mixed. According to Lindsay Murdoch, a classified wartime report blamed the Australians for the loss of Singapore, with reports that in the closing stages of the battle groups of Australian troops were seen heading away from battle leaderless, impossible to control and engaging in various crimes.[46] The division's role in the defence of Singapore has also been criticised by some authors, such as Colin Smith and several others, as being defeatist and ill-disciplined.[47][48][49] Although, others such as Peter Thompson and John Costello have argued that the 22nd Brigade was "so heavily outnumbered that defeat was inevitable",[50] while both authors argue that tactical and strategic decisions made by Bennett and Percival, were more significant.[51][52]

According to Smith, Bennett described his own troops as "wobbly" and Brigadier Harold Taylor, commander of the 22nd Brigade, told his men they were a "disgrace to Australia and the AIF."[53] Colonel Kappe, Bennett's Chief Signals Officer, related that "one party of 50 under an officer, after being steadied and persuaded to occupy a locality, soon afterwards vacated it without order."[47] According to Smith, Bennett himself is reported to have told another Australian commander, shortly before leaving his command, "I don't think the men want to fight."[54] In contrast, historian Christopher Coulthard-Clark argues that the division was one of the only British Commonwealth forces to have any tactical success in Malaya,[55] while Thompson points out that the division bore the brunt of the fighting on Singapore, arguing that despite making up only 14 percent of the Singapore garrison, the division suffered 73 percent of its casualties.[9] Equally, the British commander of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders singled out the Australian 2/29th as fighting with "great coolness" and worthy of entering battle with them,[56] while Masanobu Tsuji wrote that in Malaya the Australians "fought with a bravery…not previously seen".[57]

Rabaul

The 2/22nd Battalion—composed of 716 men—made up the majority of the combat personnel in the Lark Force, the name given to the 1,400-strong garrison concentrated in Rabaul, New Britain, from March 1941. Lark Force also included personnel from the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles, a coastal defence battery, an anti-aircraft battery, an anti-tank battery and a detachment of the 2/10th Field Ambulance.[58] The island, part of the Australian territory of New Guinea was important because of its proximity to the Japanese territory of the Caroline Islands, including a major Japanese Navy base on Truk Island. The main tasks of Lark Force were protection of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) airfield and flying boat anchorage, which were important in the surveillance of Japanese movements in the region.[59] A 130-strong detachment from the 2/1st Independent Company was detached to the nearby island of New Ireland.[60]

In January 1942, Lark Force came under heavy attack by Japanese aircraft, which neutralised coastal artillery. In the early hours of 23 January 1942, 5,000 Japanese marines began to land.[61] Some faced fierce resistance, but because of the balance of forces, many landed unopposed. Amidst the onslaught, fighting took place around Simpson Harbour, Keravia Bay and Raluana Point,[62] while a company of troops from the 2/22nd and NGVR fought to hold the Japanese around Vulcan Beach. Nevertheless, the Japanese were able to bypass most of the resistance and move inland,[63] and after a short fight, Lakunai airfield had been captured by the Japanese force.[64] Following this, the Lark Force commander, Lieutenant Colonel John Scanlan, ordered the Australian soldiers and civilians to split into small groups and retreat through the jungle.[65] Only the RAAF had made evacuation plans and its personnel were removed by flying boats and a single Hudson bomber.[66]

The Australian Army had made no preparations for guerrilla warfare, and most soldiers surrendered during the following weeks. At least 130 Australians, taken prisoner at the Tol Plantation, were massacred on 4 February 1942.[64] From mainland New Guinea, some civilians and individual officers organised unofficial rescue missions and—between March and May—about 450 troops and civilians who had managed to evade the Japanese, were evacuated by sea.[63] At least 800 soldiers and civilian prisoners of war lost their lives on 1 July 1942, when the ship on which they were sent from Rabaul to Japan, the Montevideo Maru, was sunk off the north coast of Luzon by the US submarine USS Sturgeon.[67]

A handful of Lark Force members remained at large on New Britain and—often in conjunction with indigenous people—conducted guerrilla operations against the Japanese.[60] Rabaul became the biggest Japanese base in New Guinea.[63] Allied forces landed in December 1943, although substantial Japanese forces continued to operate on New Britain until Japan surrendered in August 1945.[68][69] By the end of the Pacific War, more than 600 members of the 2/22nd Battalion had died.[70]

Ambon

The island of Ambon, in the Dutch East Indies, was perceived to be under threat from Japan because of its potential as a major air base. However, by mid-December 1941, only two flights of RAAF light bombers were deployed there, along with assorted obsolete US Navy and Royal Netherlands Navy aircraft. The 8th Division's 1,100-strong Gull Force, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Leonard Roach, commanding officer of the 2/21st Battalion,[71] arrived on 17 December. In addition to the 2/21st Battalion, it included 8th Division artillery and support units.[72] The existing Royal Netherlands East Indies Army garrison, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Kapitz, consisted of 2,800 Indonesian colonial troops,[73] with Dutch officers. Kapitz was appointed Allied commander on Ambon. Roach had visited the island before Gull Force's deployment and requested that more artillery and machine gun units be sent from Australia. Roach complained about the lack of response to his suggestions,[74] and he was replaced by Lieutenant Colonel John Scott on 13 January 1942.[71][75]

Ambon first came under attack from Japanese aircraft on 6 January. Against the Japanese seaplane bombers, the limited Allied air defences held out, but on 24 January Japanese carrier-based Zeroes began appearing and eventually the remaining aircraft were withdrawn, having been completely out-classed. On 30 January, a Japanese fleet including two aircraft carriers and about 5,000 Japanese marines and soldiers reached Ambon.[73] Although the Japanese ground forces were numerically not much bigger than the Allies, they had overwhelming superiority in air support, naval and field artillery, and tanks. In the belief that the terrain of the southern side of the island was too inhospitable for landings, the Allied troops were concentrated in the north. However, the initial Japanese landings were in the south, while other landings found the more lightly defended southern beaches.[73] The Australians had been tasked with defending the Bay of Ambon, and the Laha and Liang airfields.[76]

Following the initial landing, the Allied troops had to move quickly to re-orientate towards the advancing Japanese troops, and in the process large gaps formed in the defensive perimeter. Within a day of the Japanese landing, the Dutch forces had been surrounded and were forced to surrender. The Australians of Gull Force withdrew westwards, and held out until 3 February, when Scott surrendered. While small parties were able to escape to Australia, the majority – almost 800 men – were taken prisoner.[77]

According to Australian War Memorial principal historian, Dr. Peter Stanley, several hundred Australians surrendered at Laha Airstrip. At intervals for a fortnight after the surrender, more than 300 prisoners taken at Laha were executed. The government of Australia states that, "the Laha massacre was the largest of the atrocities committed against captured Allied troops in 1942."[78] Of Australian prisoners of war on Ambon, Stanley provides the following description of their captivity: "they suffered an ordeal and a death rate second only to the horrors of Sandakan, first on Ambon and then after many were sent to the island of Hainan late in 1942. Three-quarters of the Australians captured on Ambon died before the war's end. Of the 582 who remained on Ambon 405 died. They died of overwork, malnutrition, disease and one of the most brutal regimes among camps in which bashings were routine."[78] A total of 52 members of Gull Force managed to escape from Ambon. Of those captured from Gull Force, only 300 survived the war.[72]

Timor

In 1941, the island of Timor was divided into two territories under different colonial powers: Portuguese Timor and West Timor part of the Dutch East Indies. The Australian and Dutch governments agreed that, in the event of Japan entering World War II, Australia would provide forces to reinforce West Timor. Consequently, a 1,400-strong detachment, known as the Sparrow Force, and centred on the 2/40th Battalion, arrived at Kupang on 12 December 1941.[79]

The force was initially commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William Leggatt. It also included the Australian commandos of the 2/2nd Independent Company. Sparrow Force joined about 650 Dutch East Indies and Portuguese troops and was supported by the 12 Lockheed Hudson light bombers of No. 2 Squadron, Royal Australian Air Force,[79] and a troop from the British Royal Artillery's 79th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery.[80] The Allied forces were concentrated around the strategic airfield of Penfui.[81] As the government of Portugal declined to cooperate with the Allies, a force composed of the 2/2nd Independent Company and Dutch forces occupied Portuguese Timor, without any resistance being offered by the Portuguese Army or officials. Additional Australian support staff arrived at Kupang on 12 February, including Brigadier William Veale, who was to be the senior Allied officer on Timor.[82] By this time many of the Australians, unused to tropical conditions, were suffering from malaria and other illnesses.[83]

Timor came under attack from Japanese aircraft on 26 January. The bombing, hampered by AA guns and a squadron of US Army Air Forces fighters based in Darwin, intensified during February. Air attacks forced an Allied convoy—escorted by the destroyers HMAS Swan and HMAS Warrego—to return to Australia. It had included valuable reinforcements, such as a US Army artillery battalion and the remainder of the British AA battery.[80][84]

During the night of 19/20 February, the Imperial Japanese Army's 228th Regimental Group, began landing in Portuguese Timor. The first contact was at Dili, the capital of Portuguese Timor, where the Allies were caught by surprise. Nevertheless, they were well-prepared and after inflicting heavy casualties on the troops attacking the airfield, the garrison destroyed the airfield and began an orderly retreat towards the mountainous interior and the south coast. On the same night, Allied forces in West Timor were under extremely intense air attacks, which had already caused the RAAF force to be withdrawn to Australia.[79] Sparrow Force HQ was immediately moved further east, to its supply base at Champlong, and soon lost contact with the 2/40th.[85]

The 2/40th's line of retreat towards Champlong had been cut off by the dropping of about 500 Japanese paratroopers,[86] who established a strong position near Usua.[87] Sparrow Force HQ moved further eastward and Leggatt's men launched a sustained and devastating assault on the paratroopers. By the morning of 23 February, the Allies had killed all but 78 of the Japanese forces in front of them, but had been engaged from the rear by the main Japanese force once again.[88] With his soldiers running low on ammunition, exhausted and carrying 132 men with serious wounds, and without communications to Sparrow Force HQ Leggatt eventually acceded to a Japanese invitation to surrender.[89] The 2/40th had suffered 84 killed in action. More than twice that number would die as prisoners of war during the next two-and-a-half years.[90]

Veale and the Sparrow Force HQ force—including some members of the 2/40th and about 200 Dutch East Indies troops—continued eastward across the border,[91] and eventually joined the 2/2 Independent Company.[84] The 2/40th effectively ceased to exist, its survivors being absorbed into the 2/2nd and subsequently took part in the guerrilla campaign that was waged on Timor in the following months, before being evacuated in December 1942.[87]

Postscript 1942–1945

After a journey lasting several weeks, traversing the Strait of Malacca, Sumatra and then Java, following his escape from Malaya, Bennett arrived in Melbourne on 2 March 1942.[93][94] The Australian Prime Minister, John Curtin, publicly exonerated him.[95] However, the Australian high command effectively sidelined Bennett by appointing him commander of III Corps, a formation responsible for the defence of Western Australia. With this, he was promoted to lieutenant general, but he never commanded troops in battle again. His actions in escaping would later also be subject to a royal commission.[96]

Following the loss of its original infantry battalions, the headquarters unit of the 23rd Brigade, which had not deployed with the infantry battalions, was used to re-form a new brigade. Three Militia battalions were assigned, the 7th, 8th and 27th Battalions.[97] Reassigned to the 12th Division,[98] after garrison duty in Darwin and training in northern Queensland, the 23rd Brigade saw action in 1944–1945 against the Japanese on Bougainville.[99][100] Ostensibly the 8th Division ceased to exist in 1942; however, one of its artillery regiments, the 2/14th, which had remained in Darwin when the 23rd Brigade deployed, continued to serve until 1946, albeit attached to the 9th and 5th Divisions during their campaigns in New Guinea.[101]

During the fighting in Malaya, Singapore, Ambon, Timor and Rabaul the 8th Division lost over 10,000 men, including 2,500 killed in action, with this figure representing two-thirds of all deaths sustained by the Australian Army in the Pacific.[44] One of the division's infantry battalions, the 2/19th, lost more men killed in action than any other 2nd AIF unit.[102] Additionally, of those captured, one in three died in captivity.[44]

Commanders

The following officers commanded the 8th Division:[2]

- Major General Vernon Sturdee (1940)

- Major General Gordon Bennett (1940–1942)

Structure

The following units were assigned to the 8th Division:[2][103]

Infantry units (with state of origin, where applicable)

- 22nd Brigade, New South Wales, (NSW)

- 23rd Brigade

- 2/21st Battalion, Victoria, (Vic.)

- 2/22nd Battalion, Vic.

- 2/40th Battalion, Tasmania, (Tas.)

- 24th Brigade – to 9th Division, 1940

- 27th Brigade – from 9th Division, 1941

- 2/26th Battalion, Queensland (Qld)

- 2/29th Battalion, Vic.

- 2/30th Battalion, NSW

- Artillery regiments

- 2/9th Field Regiment, Royal Australian Artillery (RAA) – to 7th Division, 1940–1941

- 2/10th Field Regiment, RAA

- 2/11th Field Regiment, RAA – to 7th Division, 1940[104]

- 2/14th Field Regiment, RAA

- 2/15th Field Regiment, RAA

- 2/3rd Anti-Tank Regiment, RAA – to 9th Division, 1940[105]

- 2/4th Anti-Tank Regiment, RAA

- Other units

- 2/4th Machine-Gun Battalion, Western Australia (WA)

- 2/4th Pioneer Battalion

- 8th Divisional Cavalry – to 9th Division, as 9th Divisional Cavalry, May 1941.

- Engineer companies

- 2/10th Field Company, Royal Australian Engineers (RAE), Vic.

- 2/11th Field Company, RAE, Qld

- 2/12th Field Company, RAE, NSW

- 2/6th Field Park Company, RAE

- 2/4th Field Park Company, RAE, WA – to 9th Division, 1940–1941[105]

- Medical[106]

- 2/10th Australian General Hospital

- 2/13th Australian General Hospital

- 2/9th Australian Field Ambulance

- 2/10th Australian Field Ambulance including Australian Army Service Corps transport elements

- 2/4th Australian Casualty Clearing Station

- 2/2nd Australian Mobile Bacteriological Laboratory

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Farrell & Pratten 2009, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Morgan 2013, p. 4.

- ^ Farrell & Pratten 2009, p. 77.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, pp. 28–29 & 86.

- ^ Morgan 2013, p. 6.

- ^ Morgan 2013, pp. 5–6 & 12.

- ^ Farrell & Pratten 2009, p. 83.

- ^ Farrell & Pratten 2009, pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b Thompson 2005, p. 424.

- ^ Farrell & Pratten 2009, p. 101.

- ^ Thompson 2008, pp. 196 & 233.

- ^ Brayley 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Morgan 2013, p. 7.

- ^ Morgan 2013, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Morgan 2013, p. 9.

- ^ Morgan 2013, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Farrell & Pratten 2009, p. 201.

- ^ Morgan 2013, p. 11.

- ^ Morgan 2013, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Morgan 2013, p. 12.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Thompson 2008, p. 239.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, pp. 308–310.

- ^ Thompson 2008, p. 240.

- ^ Smith 2006, pp. 162–172.

- ^ a b Thompson 2005, p. 297.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 299.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 324.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 333.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 309.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 310–311.

- ^ Burfitt 1991, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, pp. 335–336.

- ^ Hall 1983, p. 179.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 314.

- ^ Hall 1983, p. 180.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 329–330.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 369.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 375.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 333–334.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, pp. 381–382.

- ^ Owen 2001, p. 202.

- ^ "Sandakan memorial". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ a b c Morgan 2013, p. 13.

- ^ Powell 2000, p. 257.

- ^ Murdoch, Lindsay (15 February 2012). "The Day the Empire Died of Shame". The Sydney Morning Herald. ISSN 0312-6315.

- ^ a b Smith 2006, p. 470.

- ^ Murfett et al 2011, p. 350.

- ^ Elphick 1995, p. 352.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 297–298.

- ^ Thompson 2008, p. 237.

- ^ Costello 2009, p. 198.

- ^ Smith 2006, p. 473.

- ^ Smith 2006, p. 497.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 204.

- ^ Smith 2006, p. 486.

- ^ Tsuji 1988, p. 193.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, pp. 394–395.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 394.

- ^ a b "1st Independent Company". Second World War, 1939–1945 units. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 199.

- ^ Gamble 2006, pp. 95–104.

- ^ a b c Moremon, John (2003). "Rabaul, 1942". Campaign history. Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 18 March 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2006.

- ^ a b Brooks 2013, p. 22.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 408.

- ^ Wilson 2005, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 674.

- ^ Keogh 1965, pp. 408–412.

- ^ Long 1963, p. 268.

- ^ "2/22nd Battalion". Second World War, 1939–1945 units. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ a b Pratten 2009, p. 326.

- ^ a b "Battalion History". Gull Force. 2/21st Battalion Association. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ a b c Yenne 2014, Chapter 15: Indies Stepping Stones.

- ^ "Fall of Ambon". Australia's War 1939–1945. Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 436.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 201.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, pp. 201–202.

- ^ a b Stanley, Peter. "Speech: "The Defence of the 'Malay barrier': Rabaul and Ambon, January 1942"". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 9 April 2009.

- ^ a b c Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 207.

- ^ a b Wigmore 1957, p. 474.

- ^ Dennis et al 1995, pp. 585–586.

- ^ Dennis et al 1995, p. 586.

- ^ "A Short History of East Timor". Department of Defence. 2002. Archived from the original on 3 January 2006. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- ^ a b "Fall of Timor". Australia's War 1939–1945. Commonwealth of Australia. Archived from the original on 27 July 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ Dennis et al 1995, p. 587.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 486.

- ^ a b "2/40th Battalion". Second World War, 1939–1945 units. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 489.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Manera, Brad. "Speech: "The Battles on Timor, 20–23 February 1942"". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 23 September 2007. Retrieved 9 April 2009.

- ^ Dennis et al 1995, p. 537.

- ^ "Ambon War Cemetery". Cemetery Details. Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ Lodge 1993, pp. 165–167.

- ^ Legg 1965, pp. 255–264.

- ^ Legg 1965, p. 264.

- ^ Legg 1965, pp. 271–277.

- ^ "Second World War, 1939–1945 Units". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "23 Australian Infantry Brigade". www.ordersofbattle.com. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ "7th Battalion (North West Murray Borderers)". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "8th Battalion (City of Ballarat Regiment)". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Kingswell 1986, pp. 112–128.

- ^ Uhr 1998, p. xii.

- ^ Brown 2012, Commonwealth Order of Battle.

- ^ "2/11th Field Regiment". Second World War, 1939–1945 units. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ a b Wilmot 1993, p. 320.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, pp. 60, 84, 362.

References

- Brayley, Martin (2002). The British Army 1939–45: The Far East. Men at Arms. Botley, Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-238-5.

- Brooks, Brenton (December 2013). "The Carnival of Blood in Australian Mandated Territory". Sabretache. LIV (4). Military Historical Society of Australia: 20–31. ISSN 0048-8933.

- Brown, Chris (2012). Battle Story Singapore 1942 (eBook ed.). Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-75248-132-6.

- Burfitt, James (1991). Against All Odds: The History of the 2/18th Battalion, AIF. Frenchs Forest, New South Wales: 2/18th Battalion, AIF Association. ISBN 978-0-646-06462-8.

- Costello, John (2009) [1982]. The Pacific War 1941–1945. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-68-801620-3.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1998). Where Australians Fought: The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles (1st ed.). St Leonards, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-611-2.

- Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey; Morris, Ewan; Prior, Robin (1995). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-553227-9.

- Elphick, Peter (1995). Singapore: The Pregnable Fortress. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-64990-9.

- Farrell, Brian; Pratten, Garth (2009). Malaya 1942. Australian Army Campaigns Series – 5. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Army History Unit. ISBN 978-0-9805674-4-1.

- Gamble, Bruce (2006). Darkest Hour: The True Story of Lark Force at Rabaul—Australia's Worst Military Disaster of World War II. St. Paul, Minnesota: Zenith Press. ISBN 0-7603-2349-6.

- Hall, Timothy (1983). The Fall of Singapore 1942. North Ryde, New South Wales: Methuen. ISBN 0-454-00433-8.

- Keogh, Eustace (1965). South West Pacific 1941–45. Melbourne: Grayflower Publications. OCLC 7185705.

- Kingswell, S.G (1986). "2/14th Australian Field Regiment AIF". In Brook, David (ed.). Roundshot to Rapier: Artillery in South Australia 1840–1984. Hawthorndene, South Australia: Investigator Press for the Royal Australian Artillery Association of South Australia. pp. 112–128. ISBN 9780858640986.

- Legg, Frank (1965). The Gordon Bennett Story: From Gallipoli to Singapore. Sydney, New South Wales: Angus & Robertson. OCLC 3193299.

- Lodge, A. B. (1993). "Bennett, Henry Gordon (1887–1962)". In Ritchie, John; Cunneen, Christopher (eds.). Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 13. Melbourne University Press. pp. 165–167. ISBN 9780522845129.

- Long, Gavin (1963). The Final Campaigns. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1 – Army. Vol. VII (1st ed.). Canberra: Australian War. pp. 241–270. OCLC 1297619.

- Morgan, Joseph (September 2013). "A Burning Legacy: The Broken 8th Division". Sabretache. LIV (3). Military Historical Society of Australia: 4–14. ISSN 0048-8933.

- Murfett, Malcolm H.; Miksic, John; Farell, Brian; Shun, Chiang Ming (2011). Between Two Oceans: A Military History of Singapore from 1275 to 1971 (2nd ed.). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish International Asia. OCLC 847617007.

- Owen, Frank (2001). The Fall of Singapore. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-139133-2.

- Powell, Alan (2000). "McLaren, Robert Kerr (1902–1956)". In Ritchie, John; Langmore, Diane (eds.). Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 15. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7.

- Pratten, Garth (2009). Australian Battalion Commanders in the Second World War. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76345-5.

- Smith, Colin (2006). Singapore Burning: Heroism and Surrender in World War II. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-101036-6.

- Thompson, Peter (2005). The Battle for Singapore: The True Story of the Greatest Catastrophe of World War II. London: Portrait Books. ISBN 0-7499-5099-4.

- Thompson, Peter (2008). Pacific Fury: How Australia and Her Allies Defeated the Japanese Scourge. North Sydney: William Heinemann. ISBN 9781741667080.

- Tsuji, Masanobu (1988). Singapore 1941–1942: The Japanese Version of the Malayan Campaign of World War II. Singapore: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19588-891-1.

- Uhr, Janet (1998). Against the Sun: The AIF in Malaya, 1941–42. St Leonards, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86448-540-0.

- Wigmore, Lionel (1957). The Japanese Thrust. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1 – Army. Vol. IV. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 3134219.

- Wilmot, Chester (1993) [1944]. Tobruk 1941. Ringwood, Victoria: Penguin Books Australia. ISBN 0-14-017584-9.

- Wilson, David (2005). The Brotherhood of Airmen. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-333-0.

- Yenne, Bill (2014). The Imperial Japanese Army: The Invincible Years 1941–42 (eBook ed.). Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-78200-982-5.

Further reading

- Aplin, Douglas Arthur (1980). Rabaul 1942. Melbourne, Victoria: 2/22nd Battalion A.I.F Lark Force Association. ISBN 978-1-875150-02-1.

- Beaumont, Joan (1988). Gull Force: Survival and Leadership in Captivity 1941–1945. Sydney, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04302-008-1.

- Christie, Robert W. (1983). A History of the 2/29 Battalion, 8th Australian Division AIF. Malvern, Victoria: 2/29 Battalion AIF Association. ISBN 978-0-9592465-0-6.

- Gaden, Caroline (2012). Pounding Along to Singapore: A Story of the 2/20 Battalion AIF and 'D" Force POW. Brisbane, Queensland: Copyright Publishing. ISBN 978-1-87634-484-9.

- Henning, Peter (1995). Doomed Battalion: Mateship and Leadership in War and Captivity. The Australian 2/40 Battalion, 1940–45. St Leonards, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86373-763-0.

- Newton, R.W. (1975). The Grim Glory of the 2/19 Battalion A.I.F. Sydney, New South Wales: 2/19 Battalion A.I.F. Association. ISBN 090913300X.

- Penfold, A.W.; Bayliss, W.C.; Crispin, K.E. (1979) [1949]. Galleghan's Greyhounds: The Story of the 2/30th Australian Infantry Battalion, 22nd November, 1940 – 10th October, 1945. Sydney, New South Wales: 2/30th Bn. A.I.F. Association. ISBN 978-090913-302-3.

- Silver, Lynette Ramsay (2004). The Bridge at Parit Sulong – An Investigation of Mass Murder. Sydney, New South Wales: The Watermark Press. ISBN 0-949284-65-3.