22nd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment

| 22nd Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry | |

|---|---|

The regimental monument of the 22nd Massachusetts on Sickles Road, near the Wheatfield, on the Gettysburg Battlefield | |

| Active | September 28, 1861 – October 17, 1864 |

| Country | United States of America |

| Allegiance | Union |

| Branch | Union Army |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | 1,393 |

| Part of | In 1863: 2nd Brigade (Tilton's), 1st Division (Barnes's), V Corps, Army of the Potomac |

| Nickname(s) | "Henry Wilson's Regiment" |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Col. Henry Wilson, Sep 1861 – Oct 1861 Col. Jesse Gove, Oct 1861 – Jun 1862 Col. William S. Tilton, Sep 1862 – May 1863 and May 1864 – Oct 1864 |

| Insignia | |

| V Corps (1st Division) badge |  |

| Massachusetts U.S. Volunteer Infantry Regiments 1861-1865 | ||||

|

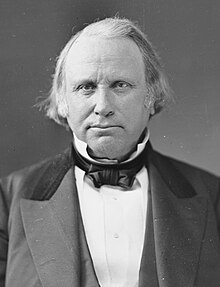

The 22nd Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry was an infantry regiment in the Union army during the American Civil War. The 22nd Massachusetts was organized by Senator Henry Wilson (future Vice-president during the Ulysses Grant administration) and was therefore known as "Henry Wilson's Regiment." It was formed in Boston, Massachusetts, and established on September 28, 1861, for a term of three years.[1]

Arriving in Washington in October 1861, the regiment spent the following winter in camp at Hall's Hill, near Arlington in Virginia. It became part of the Army of the Potomac, with which it would be associated for its entire term of service. The regiment saw its first action during the siege of Yorktown in April 1862. It was involved in the Peninsular campaign, particularly the Battle of Gaines' Mill during which it suffered its worst casualties (numerically) of the war.[2] Their worst casualties in terms of percentages took place during the Battle of Gettysburg (60 percent).[3] The 22nd Massachusetts was present for virtually all of the major battles in which the Army of the Potomac fought, including the Second Battle of Bull Run, the Battle of Antietam, the Battle of Fredericksburg, the Battle of Chancellorsville, the Battle of Gettysburg and Lieutenant General Ulysses Grant's Overland campaign. The 22nd was especially proficient in skirmish drill and was frequently deployed in that capacity throughout the war.[4]

During the siege of Petersburg in October 1864, the 22nd Massachusetts was removed from the lines and sent home to Massachusetts. Of the 1,100 who initially belonged to the unit, only 125 returned at the end of their three years of service.[5] Of these losses, roughly 300 were killed in action or died from wounds received in action, approximately 500 were discharged due to wounds or disease, and approximately 175 were lost or discharged due to capture, resignation, or desertion.[6]

Organization and early duty

Henry Wilson, a Senator from Massachusetts and chairman of the Senate's Committee on Military Affairs, witnessed the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861.[7] The disastrous defeat of the Union army convinced Wilson, and the federal government in general, of the urgent need for more troops.[8] Immediately after the battle, Wilson promised both President Abraham Lincoln and Massachusetts Governor John Andrew that he would raise a full brigade including units of infantry, artillery, cavalry and sharpshooters.[7]

Wilson's prestige encouraged the almost immediate formation of more than a dozen companies of infantry in and around Boston.[9] The pressing need to send troops to the front required Wilson to abandon his original intention of raising multiple regiments of infantry and he instead selected the 10 companies closest to readiness, thus creating the 22nd Massachusetts Regiment.[9] To this regiment were attached the 3rd Massachusetts Light Artillery and the 2nd Company Massachusetts Sharpshooters. Thus, the 22nd Massachusetts became one of the few infantry units in the Civil War with attached artillery and sharpshooters.[10]

Many of the officers of the 22nd, and some of the enlisted men, had just completed an enlistment with early war regiments (the so-called "ninety day regiments"), including the 5th Massachusetts and the 6th Massachusetts.[11] Five of the 10 companies were recruited in Boston. The remaining five came from Taunton, Roxbury, Woburn, Cambridge and Haverhill.

The regiment was signed into existence by Gov. Andrew on September 28, 1861. Wilson was appointed its first colonel. The recruits of the 22nd Massachusetts trained at a camp in Lynnfield, Massachusetts, during September and left for the front, numbering 1,117, on October 8, 1861.[12] Traveling by railroad, the regiment paused in New York City, marching down Fifth Avenue, and was received with a formal ceremony and the presentation of a national battle flag made by a committee of the ladies of New York.[13]

The 22nd arrived in Washington on October 11, and on October 13, marched across the Potomac to go into winter camp at Halls Hill, just outside Arlington, Virginia. Here the Army of the Potomac was organized during the winter of 1861–1862. The 22nd became part of Brig. Gen. John H. Martindale's brigade and was initially attached to the III Corps.[14]

On October 28, 1861, Col. Wilson resigned his command, turning the regiment over to Col. Jesse Gove. Gove, a Regular Army officer, had seen service in the Mexican–American War. He was a strict disciplinarian and, according to John Parker (the regimental historian) Gove soon became the "idol of the regiment".[15] During its first winter of service, the 22nd remained at Hall's Hill and became proficient in military drill.[16]

Peninsular campaign

Major General George B. McClellan, commanding the Army of the Potomac, determined to take the Confederate capital of Richmond via the Virginia Peninsula. This unexpected move would, in theory, allow McClellan's army to move quickly up the peninsula rather than fighting through Northern Virginia.[17] During March 1862, the Army of the Potomac was gradually transferred by water to Fortress Monroe at the end of the Virginia Peninsula. On March 10, 1862, the 22nd left their winter camp and were shipped to Fortress Monroe. By April 4, the regiment began to advance, along with many other elements of the Army of the Potomac, up the peninsula. [18]

Siege of Yorktown

As Union forces approached Yorktown, Virginia they encountered defensive lines established by Confederate Major General John B. Magruder. Initially, Magruder's forces numbered only 11,000 with McClellan's numbering 53,000.[19] McClellan also had the rest of the Army of the Potomac en route and Union troops outside of Yorktown would soon number more than 100,000.[20] Despite this, McClellan believed he faced a much larger force and settled in for a month-long siege of Yorktown.[19]

The 22nd Massachusetts saw their first action of the war near Yorktown on April 5, 1862, as the regiment was ordered to probe the Confederate lines. During the action, a portion of the regiment deployed as skirmishers under fire with great precision. The 22nd's reputation for expertise at skirmish drill would continue throughout the war and the regiment would frequently be used in this capacity.[4] Over the course of the month-long siege, the 22nd was encamped near Wormley Creek approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) southeast of Yorktown, frequently forming up at a moment's notice in expectation of an attack. On May 4, the Confederates evacuated their lines, retreating towards Richmond. The 22nd was on picket duty when rumors of the evacuation began to circulate. Colonel Gove determined to investigate and advanced the 22nd towards the Confederate trenches. According to the regimental historian, Gove was the first Union soldier to mount the Confederate works and the 22nd's flag was the first planted on the ramparts outside of Yorktown.[21]

Over the next three weeks, McClellan pushed his army northwest up the Peninsula towards Richmond. The 22nd traveled by steamship and by foot, eventually reaching Gaines' Mill, Virginia where they set up camp on May 26, 1862, about 8 miles (13 km) northeast of Richmond. During this movement, the V Corps of the Union army was formed and the 22nd became part of the 1st Brigade, 1st Division, V Corps. The regiment would remain a part of the V Corps for the duration of their service.[22]

Battle of Gaines' Mill

After seeing minor action in the Battle of Hanover Court House on May 27, the 22nd remained in camp at Gaines' Mill for nearly a month as McClellan positioned his army for an assault on Richmond.[22] The men of the 22nd could see the steeples of Richmond from their camp.[23] By this time, the regiment had been reduced to roughly 750 men due to sickness over the course of the campaign and minor casualties in action.[24]

On June 25, 1862, McClellan ordered an ineffective offensive triggering the Seven Days Battles.[25] On June 26, General Robert E. Lee, who had recently taken command of the Army of Northern Virginia, launched a daring counter-offensive intended to drive McClellan's army away from Richmond. For the 22nd, the third day of the Seven Days Battles, the Battle of Gaines' Mill, proved to be devastating as they suffered their worst casualties of the war.[26]

On June 27, 1862, the V Corps, including the 22nd, pulled back to Gaines' Mill after successfully repulsing the Confederate counter-offensive at Mechanicsville. Although McClellan regarded Mechanicsville as a victory, he had lost the initiative to Lee and was already pulling his army away from Richmond despite holding the advantage of numbers.[25] During the Battle of Gaines' Mill, the 22nd was held in reserve, behind the other regiments of their brigade. Over the course of the day, the Union regiments in their front successfully repulsed several Confederate charges. But at 6 p.m., the Union lines broke and the 22nd was suddenly exposed to the brunt of the Confederate attack. With the 22nd flanked on both sides, Colonel Gove soon gave the order to retire. Then, reluctant to yield the ground, he ordered the 22nd to about face and stand fast. Colonel Gove was killed almost immediately after delivering this order. His body was never recovered. Captain John Dunning, commanding Company D, was also killed. In the subsequent fighting the 22nd lost 71 killed, 86 wounded and 177 captured.[27] Maj. William S. Tilton was captured and later paroled. With Lieutenant Colonel Charles Griswold on sick leave, command fell to Captain Walter S. Sampson. The 22nd eventually fell back to a ridge where they were able to make a stand with the 3rd Massachusetts Battery.[26]

The regimental historian wrote, "It was a sad night for the Twenty-second. Not a man but had lost a comrade, for one-half of those who marched in the morning were no longer in the ranks. Colonel Gove was killed and that was, without a doubt, one of the greatest disasters of the day."[26] The 22nd Massachusetts and the 83rd Pennsylvania suffered roughly the same casualty rate and the two regiments lost more men killed in action than any other units on the field that day.[28] Both regiments lost their colonels.

Battle of Malvern Hill

The 22nd played little role in the next three days of fighting, with the exception of brief action during the Battle of Glendale during which the regiment supported the 3rd Massachusetts Battery and was credited with saving the battery from capture.[24] By June 30, the regiment was encamped near Malvern Hill with the rest of the V Corps. The Army of the Potomac had retreated roughly 15 miles (24 km) during a running fight over the past six days and was suffering low morale.[29] However, by July 1, the Union army was in a strong position and, that day, during the Battle of Malvern Hill, the Army of the Potomac finally stopped Lee's offensive. The 22nd, during this action, was ordered to support the 5th United States Battery. While firing in line with the battery, the men of the 22nd sang "John Brown's Body" and exhausted their 60 rounds of ammunition.[30] After they were pulled off the line, the 22nd marched through the night to Harrison's Landing. The regiment lost nine killed, 41 wounded and eight prisoners during the Battle of Malvern Hill, roughly 20 percent.[31]

Northern Virginia campaign

On July 15, 1862, while the 22nd was still in camp at Harrison's Landing, Lieutenant Colonel Griswold returned from sick leave, was promoted to colonel and took command of the regiment. On August 14, the regiment broke camp and marched with the V Corps to Newport News, Virginia.[32] McClellan had abandoned his Peninsular campaign and had been ordered to move the Army of the Potomac back to Northern Virginia to support the advance of a newly organized Union army, the Army of Virginia, under the command of Major General John Pope. The 22nd was transported by steamship to Aquia Creek, Virginia, by railroad to Fredericksburg, and by August 28 they had marched with the V Corps to Gainesville, Virginia.[32] In the course of this march, the 22nd was detached from their brigade and assigned to picket duty. As a result, the regiment played no role in the subsequent Second Battle of Bull Run on August 30, 1862, in which the rest of their brigade was heavily engaged.[32]

Following the disastrous defeat of Pope's army at the Second Battle of Bull Run, the Army of the Potomac, with McClellan still in command, was quickly reorganized outside of Washington during the first week of September 1862. The 22nd returned to their old camp at Halls Hill, Virginia, which they had occupied the previous winter. Sen. Wilson visited the 22nd at Halls Hill. Finding just 200 war-torn men in contrast to the 1,100 he had recruited, Wilson, with tears in his eyes, asked, "Is this my old regiment?"[33]

Maryland campaign

The 22nd did not stay long at Halls Hill. With the Army of the Potomac in disarray and the Confederates on the offensive, an attack on Washington was expected at any moment. The 22nd was shifted to several different defensive entrenchments outside of Arlington, Virginia during the first week of September.[34] Lee, however, set out to invade Western Maryland, the lead elements of his army crossing the Potomac on September 4, 1862. McClellan was slow to react to this development, but began moving elements of the Army of the Potomac northwest from Washington on September 6. On September 10, Lieutenant Colonel Tilton, having been released from Libby Prison through an officer exchange, returned to the 22nd and took command. The 22nd left Arlington on September 12. The march through Maryland was remembered by the 22nd as wearisome and profoundly dusty.[35]

Battle of Antietam

As the Union army approached, Lee chose to make a stand at Sharpsburg, Maryland along Antietam Creek. On September 17, 1862, the armies engaged in the Battle of Antietam. The V Corps was held in reserve in the center of Union lines during the battle. The 22nd had a clear view of both flanks of the Union army and watched the assaults that took place over the course of the day. The V Corps, however, took no part in these assaults. Historians have criticized McClellan for his uncoordinated attacks at Antietam and for not committing the V Corps which might have broken Lee's army.[36]

Battle of Shepherdstown

Lee evacuated Sharpsburg on September 18, retreating towards Virginia. The 22nd, with other regiments of its corps, moved through the town the next day. As the Confederate army crossed over the Potomac, two divisions of the V Corps, including the 22nd Massachusetts, were ordered to cross into Virginia via Blackford's Ford at Shepherdstown, Virginia (now West Virginia).[37] The movement was an ineffective attempt on McClellan's part to prevent the escape of Lee's army.[38] The pursuing Union forces were hit with a decisive Confederate counterattack at the Battle of Shepherdstown on September 20, 1862, causing the Union divisions to quickly retreat in disorder back across the Potomac. The 22nd struggled across the river and reached the Maryland shore "half drowned".[39] The engagement ended any efforts by McClellan to pursue Lee's army.[38]

Fredericksburg campaign

The 22nd Massachusetts remained in camp on the Maryland side of the Potomac for more than a month. On October 30, 1862, the 22nd broke camp and began marching south into Virginia. On November 5, Lincoln removed McClellan from command of the Army of the Potomac and replaced him with Major General Ambrose Burnside.[40] The army moved to Falmouth, Virginia, where Burnside spent weeks orchestrating his attack on Fredericksburg just across the Rappahannock River.[41]

Battle of Fredericksburg

The Army of the Potomac, having constructed pontoon bridges across the Rappahannock, commenced the Battle of Fredericksburg on the morning of December 13, 1862. The Confederate army occupied the city of Fredericksburg and a high ridge behind the city known as Marye's Heights. By late morning, Union forces had taken the city and began the assault on Marye's Heights. At approximately 3:30 in the afternoon the 22nd Massachusetts, with the rest of Colonel James Barnes's brigade, crossed one of the pontoon bridges and moved through a railroad cut to the outskirts of the city.[42] The regiment numbered about 200 men.[43] Barnes's brigade was ordered to relieve a brigade of the IX Corps which had made a charge on the stone wall along Marye's Heights and become pinned down by Confederate fire.[44] By the time they formed up battle lines on the open slope in front of Marye's Heights, the 22nd was under intense artillery fire from the Confederates. According to the regimental historian, "the men instinctively turned their sides to the storm" of bullets, shot and shell as they advanced and casualties were heavy.[42] Their brigade reached Nagle's brigade and the 22nd relieved the 12th Rhode Island, taking shelter on ground covered by that regiment's casualties.[42] Here the 22nd fired in prone position, exhausting their ammunition, yelling and cheering to keep up their courage.[45]

Around nightfall, the 22nd was relieved by the 20th Maine. Falling back to a sunken road on the outskirts of Fredericksburg, the 22nd was still exposed to Confederate artillery and took cover as best they could. Many of the regiment had thrown away their haversacks in an effort to lighten their burden before the charge and were subsequently without food. During the night, they resorted to searching the haversacks of fallen soldiers for rations.[46]

Just before dawn on December 14, ammunition was issued and the 22nd moved forward slightly, to about the position on the open slope that they had occupied the day before. Here they spent another day pinned to the ground, unable to advance or retire due to the constant fire of Confederate riflemen. Nightfall finally brought relief as another unit took their place on the field and the 22nd retired to the city of Fredericksburg.[47]

The 22nd spent the next day, December 15, in the city of Fredericksburg, hearing rumors that Burnside intended to personally lead another assault on the heights. But no attack materialized, night came, and the V Corps crossed the pontoon bridges back to Falmouth, with the 22nd acting as rear guard. During the battle of Fredericksburg, the 22nd lost 12 killed and 42 wounded, roughly 28 percent casualties.[48]

Camp Gove

The 22nd set up winter camp on the outskirts of Falmouth, Virginia on December 22, 1862. The camp was located about 1 mile (1.6 km) northeast of Stoneman's Station, now known as Leeland Station.[49] The men built crude log huts with improvised chimneys made of mud and sticks. Here the regiment would remain for approximately six months during the first half of 1863. The camp was named "Camp Gove" in honor of their fallen colonel.[41]

While at Camp Gove, the 22nd Massachusetts, with the rest of the V Corps, was frequently deployed on expeditions of varying importance. On January 20, 1863, the regiment took part in the infamous Mud March during which Burnside attempted to attack the flank of the Confederate army which was still encamped at Fredericksburg. The roads were so impassable that the Union army bogged down and the entire effort was aborted. The 22nd returned to Camp Gove five days after they left.[50]

The 22nd also participated, in a minor capacity, in the Battle of Chancellorsville. On April 27, Brig. Gen. Charles Griffin's division, including the 22nd, was ordered to secure the fords along the Rapidan River. It was a long, rapid, forced march for the division. The Confederate army launched a daring and successful flank attack against the Army of the Potomac at Chancellorsville on May 2, 1863, during which the 22nd saw little action. The Union army, badly defeated, retreated back across the Rappahannock and the 22nd returned to Camp Gove on May 8.[50]

In late May, Colonel Tilton of the 22nd was promoted to the command of the brigade and Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Sherwin assumed command of the 22nd.[50]

Gettysburg campaign

On May 28, 1863, the 22nd Massachusetts packed up and left Camp Gove. Their corps was deployed along the Rappahannock, upriver of Fredericksburg, as an observation force to determine what movements were being made by Lee's army.[50] In this, they were unsuccessful. Lee's army slipped away from Fredericksburg on June 3 and began a long march that would lead to an invasion of Pennsylvania. The 22nd learned of Lee's movements on June 13 when the V Corps was ordered to march northward. By this time, the entire Army of the Potomac was on the move.[51] The two armies would eventually meet, almost three weeks later, at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.[52]

Battle of Gettysburg

By June 30, 1863, the 22nd had reached Union Mills, Maryland after weeks of hard marching. On July 1, they marched 10 miles (16 km) to Hanover, Pennsylvania, completely unaware that elements of the Army of the Potomac had engaged the Confederates some 15 miles (24 km) away in the first day of fighting during the Battle of Gettysburg. Not long after they settled down for the evening, orders came for them to march. The 22nd, and the rest of the V Corps, marched through the night to Gettysburg, reaching the battle around dawn on July 2. The V Corps was stationed well behind the center of the Union lines, awaiting deployment to one flank or the other. The men of the 22nd fell to the ground and caught a few hours sleep even as the second morning of battle raged not far from their position.[53] At Gettysburg, the regiment had only 67 men.[3]

At about 4 p.m., the V Corps was ordered to advance in support of the III Corps. Barnes's division passed north of Little Round Top and deployed just south of the Wheatfield along a small, stony hill within sight of the Rose farmhouse which was directly in their front. Once deployed, the soldiers of the 22nd began to pile paper cartridges on the ground in front of them, sensing they would be holding that ground for some time.[54]

As the III Corps retreated, Tilton's brigade was directly exposed to the oncoming Confederates. The 22nd was soon engaged by Kershaw's brigade of South Carolinians. Apparently unnerved by the sudden Confederate advance and perceiving that his right flank was exposed, Brig. Gen. Barnes, the 22nd's division commander, ordered the withdrawal of his division.[55] The men of the 22nd picked up their cartridges and yielded the ground. This withdrawal back across the Wheatfield to Trostle's Farm left a gap in the Union line. Barnes and Tilton were both subject to much criticism from other officers on the field for this withdrawal, which Barnes apparently ordered without consulting his superiors.[56] The gap left by Barnes's division was eventually filled by brigades of the II Corps after hard fighting. The 22nd fought from their new position along a stone wall on Trostle's Farm and was eventually pulled back to the north side of Little Round Top by about 6 p.m.[57]

On the third and final day of the Battle of Gettysburg, the 22nd was posted in the ravine between Little Round Top and Big Round Top. The ground was heavily wooded and rocky. Here they piled up stones and took shelter from the Confederate sharpshooters in Devil's Den about 500 yards (460 m) to their front.[3] The regiment remained in this position while Pickett's Charge, Lee's unsuccessful attempt to break Union lines, took place well north of the 22nd's position.[58]

During the Battle of Gettysburg, the regiment suffered 15 killed and 25 wounded or 60 percent. In terms of percentages, this represented the regiment's highest number of casualties in an individual battle.[3]

Camp Barnes

On September 9, 1863, the 22nd was reinforced by 200 draftees, once again fielding respectable numbers. During the latter half of 1863, the 22nd was involved in some minor engagements along the Rappahannock River including the Second Battle of Rappahannock Station and the Battle of Mine Run. No significant progress was made by the Army of the Potomac that fall, and the 22nd settled into a camp near Brandy Station, Virginia which they named "Camp Barnes" after their division commander who had been wounded at Gettysburg. In March 1864, Col. Tilton was relieved of command of his brigade and returned to the command of the 22nd Massachusetts.[3]

Overland campaign and the siege of Petersburg

On April 30, 1864, the 22nd broke camp and marched southeast from Rappahannock Station. Lieutenant General Ulysses Grant had now assumed command of Union forces as general-in-chief and although Major General George Meade remained in command of the Army of the Potomac, Grant was determined to follow the army in the field, directing its movements. The resulting campaign during the spring of 1864 was known as the Overland campaign and saw relentless attacks on the part of the Union army under Grant. The reinforced 22nd began the campaign with about 300 men. By the close of the campaign, the regiment would be reduced to about 100.[59]

During the Battle of the Wilderness on May 5–6, 1864, the regiment lost 15 killed and 36 wounded.[59] The regiment was heavily engaged in the Battle of Spotsylvania on May 9–10. On May 10, the 22nd was ordered to take a line of rifle pits that had been abandoned by Union troops and taken by the Confederates. The 22nd deployed as skirmishers under the command of Major Mason Burt and advanced under heavy fire. The regiment was successful in taking the Confederate position, but at a heavy cost of 17 killed and 57 wounded, nearly 50 percent.[60] During the Battles of North Anna and Totopotomoy Creek, the 22nd acted again as skirmishers, winning praise for their maneuvers in advance of their division.[61]

By this time, Grant had pushed Lee's army south to within 10 miles (16 km) of Richmond. The final assault of the Overland campaign came with the Battle of Cold Harbor—a number of futile attempts by Grant over the course of June 1–3 to break the heavily entrenched Confederate lines. The 22nd was active during all three days of the battle, particularly on June 3 when they were again deployed as skirmishers in front of their brigade, now commanded by Col. Jacob B. Sweitzer, in the vicinity of Bethesda Church. Sweitzer's brigade, with the 22nd in the advance, made a charge across open ground, pushing back the Confederate forces in their front. During the Battle of Cold Harbor, the 22nd lost 11 killed and 11 wounded, now numbering less than 100.[61]

Lee's army now dug in around Petersburg, Virginia and the long siege of Petersburg commenced with several frontal assaults on the Confederate position. The 22nd took part in the assault on June 18, 1864. Again the regiment was deployed as skirmishers in front of their brigade. They were ordered to take a ravine alongside the Norfolk Railroad. Advancing at a run in the face of heavy canister fire, the 22nd reached the ravine. However, in that position they were subjected to severe musket and artillery fire from the Confederates, and so they pushed forward to the Norfolk Railroad cut, forcing the Confederates back to their entrenchments. In the assault on Petersburg, the 22nd lost seven killed and 14 wounded.[62]

During the latter part of June 1864, the 22nd was marched to several different positions along the siege lines outside of Petersburg, expecting to participate in another assault. Finally, around June 30, 1864, the regiment was stationed in the trenches and remained there for six weeks.[62]

Mustering out

On August 8, 1864, the 22nd was pulled from the trenches and posted on guard duty at City Point, Virginia, the main supply depot of the Union army. Maj. Gen. Meade had specifically requested a depleted unit whose term of service was nearly up for this duty.[63] They remained there until October 3, their three years of service having expired. Those of the regiment who had chosen to re-enlist, along with the remaining draftees who had joined the unit in 1863, were consolidated with the 32nd Massachusetts. The remaining men of the 22nd who had served their three years and did not wish to re-enlist, 125 in number, returned to Boston by railroad, arriving on October 10.[62] After ceremonies in Boston, the regiment was officially mustered out on October 17, 1864.[64]

Legacy

Notable members

After the war, several former members of the 22nd Massachusetts went on to achieve notable accomplishments in various fields.

Senator Henry Wilson, founder of the unit, was well known during the war for his antislavery political stance. After the war, he became one of the leading Radical Republicans in Congress, pressing for civil rights for former slaves and harsh treatment of former Confederates.[65] In 1872, the same year he was elected vice-president under Ulysses Grant, Wilson published the first volume of his History of the Rise and Fall of the Slave Power, a severe criticism of slave owners and their primary role, according to Wilson, in bringing about the Civil War.[66]

Nelson A. Miles joined the 22nd Massachusetts as a first lieutenant but was soon transferred. In 1862, he became colonel of the 61st New York Infantry. After the war, Miles became a colonel in the Regular Army and steadily rose through the ranks, ultimately becoming the Commanding General of the United States Army in 1895.[67]

Arthur Soden served as a hospital steward with the 22nd Massachusetts. After the war, he went on to become an influential figure during the formative years of Major League Baseball as president of the Boston Red Stockings and, briefly, as the president of the National League.[68]

Marshall S. Pike was a well-known singer, poet and songwriter before the war. He served as drum major for the 22nd regimental band and was taken captive at the battle of Gaines' Mill. After his release in December 1862, he was discharged and resumed his career as an entertainer and songwriter.[69]

Regimental Association

As the remains of the regiment were en route back to Boston in October 1864, the officers met to form a regimental association to organize annual reunions of the officers. These reunions were eventually opened to enlisted men and the reunions became large events. In 1870, the regimental association was more formally organized with the election of officers and the establishment of by-laws. Its purpose was "to preserve the history and perpetuate [the 22nd's] deeds and their men". The reunions were typically held at the Parker House in Boston. The association organized a number of projects in honor of the 22nd's former members including placing a bust of Henry Wilson in the Massachusetts State House and the construction, in 1885, of the 22nd Massachusetts regimental monument near the Wheatfield on the Gettysburg battlefield.[70]

Reenactment group

The 22nd Massachusetts is memorialized by a group of Civil War re-enactors, the 22nd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, Inc., who portray Company D of the regiment at various civic events, educational programs, and Civil War re-enactments. The group is based on the South Shore of Massachusetts.[71]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 24.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 123.

- ^ a b c d e Bowen (1889), p. 354.

- ^ a b Parker (1887), p. 84.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 488.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 490.

- ^ a b Parker (1887), p. 1.

- ^ Catton (2004), p. 51.

- ^ a b Bowen (1889), p. 346.

- ^ Katcher (2002), p. 8.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 5–12.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 3, 100.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 37.

- ^ Bowen (1889), p. 347.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 49.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 60.

- ^ Catton (2004), p. 64.

- ^ Bowen (1889), p. 348.

- ^ a b Wert (2005), p. 68.

- ^ Wert (2005), p. 66.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 94.

- ^ a b Bowen (1889), p. 349.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 114.

- ^ a b Parker (1887), p. 127.

- ^ a b Wert (2005), p. 103.

- ^ a b c Parker (1887), p. 122.

- ^ Bowen (1889), p. 350.

- ^ Wert (2005), p. 105.

- ^ Wert (2005), p. 108.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 128.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 130.

- ^ a b c Bowen (1889), p. 351.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 163.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 183.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 185.

- ^ McPherson (2002), p. 129.

- ^ Wert (2005), p. 171.

- ^ a b McPherson (2002), p. 131.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 200.

- ^ Wert (2005), p. 174.

- ^ a b Bowen (1889), p. 352.

- ^ a b c Parker (1887), p. 226.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 201.

- ^ Powell (1896), p. 388.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 227.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 228.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 232.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 236.

- ^ Rappahannock Valley Civil War Roundtable, October 2, 2009, The Army of the Potomac in Stafford County.

- ^ a b c d Bowen (1889), p. 353.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 323.

- ^ Wert (2005), p. 271.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 329–332.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 334.

- ^ Sears (2003), p. 286.

- ^ Pfanz (1987), p. 261.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 336.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 341.

- ^ a b Bowen (1889), p. 355.

- ^ Bowen (1889), p. 356.

- ^ a b Bowen (1889), p. 357.

- ^ a b c Bowen (1889), p. 358.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 484.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 493.

- ^ Foner (1990), p. 104.

- ^ Stampp (1991), p. 28.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 582.

- ^ Caruso (1995), p. 317.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 588.

- ^ Parker (1887), p. 538–548.

- ^ 22nd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Reenactors, 2017.

Sources

- Bowen, James L. (1889). Massachusetts in the War, 1861–1865. Springfield, Massachusetts: Clark W. Bryan & Co. OCLC 1986476.

- Caruso, Gary (1995). The Braves Encyclopedia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 317]. ISBN 1-56639-384-1.

The Braves Encyclopedia.

- Catton, Bruce (2004) [1960]. The Civil War. New York: American Heritage, Inc. ISBN 0-618-00187-5.

- Foner, Eric (1990). A Short History of Reconstruction, 1863–1877. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-055182-8.

- Katcher, Philip (2002). Sharpshooters of the American Civil War, 1861–1865. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-463-9.[permanent dead link]

- McPherson, James M. (2002). Crossroads of Freedom: Antietam, The Battle That Changed the Course of the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513521-0.

- Parker, John L. (1887). Henry Wilson's Regiment: History of the Twenty-Second Massachusetts Infantry. Boston: Rand Avery Co. OCLC 544347.

- Pfanz, Harry W. (1987). Gettysburg – The Second Day. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1749-X.

- Powell, William H. (1896). The Fifth Army Corps. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 476330578.

- Sears, Stephen W. (2003). Gettysburg. New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-86761-4.

- Stampp, Kenneth M. (1991) [1965]. The Causes of the Civil War. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-75155-7.

- Wert, Jeffrey D. (2005). The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-2506-6.

- The Rappahannock Valley Civil War Roundtable (October 2, 2009). "The Army of the Potomac in Stafford County, 1862–1863: A Driving Tour". Central Rappahannock Regional Library. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved February 12, 2010.

- "22nd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Reenactors". 22nd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, Inc. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

External links