COVID-19 pandemic in Japan

| COVID-19 pandemic in Japan | |

|---|---|

Confirmed cases per 100,000 residents by prefecture[a] | |

| Disease | COVID-19 |

| Virus strain | SARS-CoV-2 |

| Location | Japan |

| First outbreak | Wuhan, Hubei, China |

| Date | 16 January 2020 - 21 April 2023 (3 years, 3 months and 5 days) |

| Confirmed cases | 33,803,572[1] |

| Recovered | 33,728,878 (updated 23 July 2023) [2] |

Deaths | 74,694[1] |

| Fatality rate | 0.22% |

| Vaccinations | |

| Government website | |

| Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (in Japanese) | |

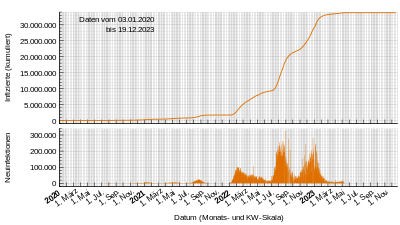

The COVID-19 pandemic in Japan has resulted in 33,803,572[1] confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 74,694[1] deaths, along with 33,728,878 recoveries.

The Japanese government confirmed the country's first case of the disease on 16 January 2020 in a resident of Kanagawa Prefecture who had returned from Wuhan, China.[3] The first known death from COVID-19 was recorded in Japan on 14 February 2020. Both were followed by a second outbreak introduced by travelers and returnees from Europe and the United States between 11 March 2020 and 23 March 2020.[4][5] According to the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, the majority of viruses spreading in the country derive from the European type, while those of the Wuhan type began disappearing in March 2020.[6][7][8]

According to the official press release of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, at the end of 2020, the cumulative number of cases was 230,304 and the number of deaths was 3,414.[9]

The COVID-19 vaccination in Japan began on 17 February 2021, more than a month after the first anniversary of the beginning of the pandemic in the country was commemorated. As of 22 October 2021, about 96.4 million people in Japan received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, while about 86.9 million were fully vaccinated.

The Japanese government adopted various measures to limit or prevent the outbreak.[10] Some observers describe this approach as constituting a unique "Japan Model" of COVID-19 response.[11] On 30 January 2020, former prime minister Shinzo Abe established the Japan Anti-Coronavirus National Task Force to oversee the government's response to the pandemic.[12][13] On 27 February 2020, he requested the temporary closure of all Japanese elementary, junior high, and high schools until early April 2020.[14] On 7 April 2020, Abe proclaimed a one-month state of emergency for Tokyo and the prefectures of Kanagawa, Saitama, Chiba, Osaka, Hyogo, and Fukuoka.[15] On 16 April 2020, the declaration was extended to the rest of the country for an indefinite period.[16] The state of emergency was lifted in an increasing number of prefectures during May 2020, extending to the whole country by 25 May 2020.[17]

On 7 January 2021, Suga declared a state of emergency for Tokyo and the prefectures of Chiba, Saitama and Kanagawa, effective from 8 January until 7 February.[18] Japan's death rate per capita from coronavirus is one of the lowest in the developed world, despite its aging population. Factors speculated to explain this include the government response, a milder strain of the virus, cultural habits such as bowing etiquette and wearing face masks, handwashing with sanitizing equipment, a protective genetic trait, and a relative immunity conferred by the mandatory BCG tuberculosis vaccine.[19] In December 2021, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare reported the number of excess deaths through July. The excess death toll was 12000 in COVID-19 and 11000 from natural causes due to the aging of the population, but the death toll from pneumonia fell by 5000 as a result of infection control measures taken by people.[20]

The pandemic continued to be a concern for the 2020 Summer Olympics. Although the Japanese government and the International Olympic Committee negotiated its postponement until 2021, reports[which?] concluded that a cancellation of the games was still an option – although prime minister Yoshihide Suga dismissed the idea of it happening.[21] In the end, the Olympics went ahead, with sports events running between 23 July and 8 August 2021 and multiple restrictions in place to avoid the breakouts of the virus.[22]

At the end of 2021, the cumulative number of cases was 1,733,725 and the number of deaths was 18,393.[23]

At the end of 2022, the cumulative number of cases was 29,212,535 and the number of deaths was 57,262.[24]

On May 8, 2023, the Japanese government changed the classification of COVID-19 from category 2 to category 5 under the Infectious Disease Control Law. Under Category 2, the government was able to take strict measures against COVID-19, such as urging the public to stay indoors and recommending hospitalization for those infected, but under Category 5, infection control measures are now left to the discretion of the individual.[25] According to records as of the end of May 7, 2023, the last day of the official press release issued by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare based on daily statistics of the number of cases and deaths, the cumulative number of cases was 33,802,739 and the number of deaths was 74,669.[26]

Timeline

Japan is one of the countries with at least a million COVID-19 cases, as well as the only country in East Asia with at least a million COVID-19 cases. At the beginning of the 2020 Summer Olympics, there were nearly 860,000 cases in the country.

The COVID-19 pandemic in Japan can be divided into five waves based on the genome sequence of the country's COVID-19 virus.[6][7][27][28] The National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID) of Japan has determined from its genetic research that the COVID-19 variant of the first wave is derived from the Wuhan type that is prevalent in patients from China and other countries in East Asia. After entering Japan in January 2020 through travelers and returnees from China, the virus caused numerous infection clusters across the country before beginning to subside in March. Japanese medical surveillance confirmed its first case of the virus on 16 January 2020 in a resident of Kanagawa Prefecture who had returned from Wuhan.[3][29][30] On 14 February 2020, the country confirmed the first COVID-19 death.

The first wave was followed by a second one that originated from a COVID-19 variant of the European type that is traced back to early patients from France, Italy, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.[6][28] Japanese medical surveillance detected the second wave on 26 March 2020 when the government's expert panel concluded the likelihood of a new outbreak caused by travelers and returnees from Europe and the United States between 11 March 2020 and 23 March 2020.[4][5] The NIID has established that the majority of viruses spreading in Japan since March is the European type. This has led it to conclude that the data "strongly suggests" that the Japanese government has succeeded in containing the Wuhan variant and that it is the European variant that is spreading across the country.[31]

According to the official press release of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, at the end of 2020, the cumulative number of cases was 230,304 and the number of deaths was 3,414.[9]

At the end of 2021, the cumulative number of cases was 1,733,725 and the number of deaths was 18,393.[23]

At the end of 2022, the cumulative number of cases was 29,212,535 and the number of deaths was 57,262.[24]

On May 8, 2023, the Japanese government changed the classification of COVID-19 from category 2 to category 5 under the Infectious Disease Control Law. Under Category 2, the government was able to take strict measures against COVID-19, such as urging the public to stay indoors and recommending hospitalization for those infected, but under Category 5, infection control measures are now left to the discretion of the individual.[25] According to records as of the end of May 7, 2023, the last day of the official press release issued by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare based on daily statistics of the number of cases and deaths, the cumulative number of cases was 33,802,739 and the number of deaths was 74,669.[26]

Statistics

Case fatality rate

The trend of case fatality rate for COVID-19 from 16 January, the day first case in the country was recorded.[32]

Government response

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

Phase 1: Containment

The initial response of the Japanese government to the COVID-19 outbreak was a policy of containment that focused on the repatriation of Japanese citizens from Wuhan, the point of origin of the pandemic, and the introduction of new border control regulations.[33]

On 24 January 2020, Abe convened the Ministerial Meeting on Countermeasures Related to the Novel Coronavirus at the Prime Minister's Office with members of his Cabinet in response to a statement by the World Health Organization (WHO) confirming human-to-human transmission of the coronavirus. Abe announced that he would introduce appropriate countermeasures to the disease in coordination with the NIID.[34]

On 27 January 2020, Abe designated the new coronavirus as an "infectious disease" under the Infectious Diseases Control Law, which allows the government to order patients with COVID-19 to undergo hospitalization. He also designated the disease as a "quarantinable infectious disease" under the Quarantine Act, which allows the government to quarantine people suspected of infection and order them to undergo diagnosis and treatment.[35] On 30 January 2020, Shinzo Abe,[36] Abe announced the establishment of the "Novel Coronavirus Response Headquarters" (新型コロナウイルス感染症対策本部), which meets at the Prime Minister's Official Residence and is run by a task force led by Deputy Chief Cabinet Secretary for Crisis Management [37] The initial roster of the task force includes 36 high-ranking bureaucrats from several of the Ministries of Japan. The headquarters acts as the site of Abe's decision-making process on the country's virus countermeasures.

On 31 January 2020, Abe announced that the government was prioritizing the repatriation of Japanese citizens from Hubei Province. Officials negotiated with Chinese authorities to dispatch five chartered flights to Wuhan from 29 January 2020 to 17 February 2020.[33]

On 1 February 2020, the Japanese government enacted restrictions to deny entry to foreign citizens who had visited Hubei Province within 14 days and to those with a Chinese passport issued from there.[38] On 12 February 2020, it expanded those restrictions to anyone who had a recent travel history to and from Zhejiang Province or had a Chinese passport issued from there.[39]

On 5 February 2020, Abe invoked the Quarantine Act to place the cruise ship Diamond Princess under quarantine in Yokohama. Quarantine officers were dispatched to the ship to prevent the disembarkation of crew and passengers, and to escort infected patients to medical facilities.[40]

On 6 February 2020, Abe invoked the Immigration Control and Refugee Act to deny entry to the cruise ship MS Westerdam from Hong Kong after one of its passengers tested positive for COVID-19.[41]

Reinforcement of medical service system

After the COVID-19 outbreak on the cruise ship Diamond Princess, the Japanese government shifted its focus from a policy of containment to one of prevention and treatment because it anticipated increasing community spread within Japan. This policy prioritized the creation of a COVID-19 testing and consultation system based on the NIID and the government's 83 existing municipal and prefectural public health institutions that are separate from the civilian hospital system. The new system handles the transfer of COVID-19 patients to mainstream medical facilities to facilitate patient flow, triage, and the management of limited testing kits on their behalf to prevent a rush of infected and uninfected patients from overwhelming healthcare providers and transmitting diseases to them. By regulating COVID-19 testing at the national level, the Abe Administration integrated the activities of the national government, local governments, medical professionals, business operators, and the public in treating the disease.[35]

On 1 February 2020, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare instructed municipal and prefectural governments to establish specialized COVID-19 consultation centers and outpatient wards at their local public health facilities within the first half of the month.[42] Such wards would provide medical examinations and testing for suspected carriers of the disease to protect general hospitals from infection.[42]

On 5 February 2020, Abe announced that the government would begin preparations to strengthen COVID-19 testing capabilities at the NIID and 83 municipal and prefectural public health institutions that are designated by the government as official testing sites. Without a uniform diagnosis kit for the disease, the government has relied on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests to check for infections. As few mainstream medical facilities in Japan can conduct PCR tests, Abe also promised to increase the number of institutions with such kits, including universities and private companies.[40]

On 12 February 2020, Abe announced that the government would expand the scope of COVID-19 testing to include patients with symptoms based on the discretion of local governments. Previously, testing was restricted to those with a history of traveling to Hubei Province.[43][44] On the same day, the Ministry of Health and NIID contracted SRL Inc to handle PCR clinical laboratory testing.[45] Since then, the government has partnered with additional private companies to expand laboratory testing capabilities and to work towards the development of a rapid testing kit.[46]

On 14 February 2020, Abe introduced the government's coronavirus consultation system to coordinate medical testing and responses with the public. The Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare worked with local governments to establish 536 consultation centers that covered every prefecture within the country to provide citizens with instructions on how to receive COVID-19 testing and treatment. The general public needs to contact a consultation center by phone to get tested at one of the government's specialized outpatient wards (帰国者・接触者外来).[47][48]

On 16 February 2020, Abe convened the government's first Novel Coronavirus Expert Meeting (新型コロナウイルス感染症対策専門家会議) at the Prime Minister's Office to draft national guidelines for COVID-19 testing and treatment.[49] The meeting was chaired by Wakita Takaji, Director of the NIID, who brought together ten public health experts and medical professionals from across Japan to coordinate a response to the virus with Abe and the government's coronavirus task force in a roundtable format. The main concern of the Japanese medical establishment was overcrowding of hospitals by uninfected patients with light cold symptoms who believed that they had COVID-19. Medical representatives claimed that such a panic would strain medical resources and risk exposing those uninfected patients to the disease.[50][51]

On 17 February 2020, the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare released national guidelines for COVID-19 testing to each of the municipal and prefectural governments and their public health centers.[52][53] It instructed doctors and public health nurses who staff the consultation centers to limit consultations to people with the following conditions: (1) cold symptoms and a fever of at least 37.5 °C (or need to take antipyretic medication) for over four days; and (2) extreme fatigue and breathing difficulties. The elderly, people with pre-existing conditions, and pregnant women with cold symptoms can receive consultation if they have had them for two days.[52]

On 22 February 2020, Health Minister Katsunobu Kato announced that the Japanese government was looking into the use of favipiravir, an anti-influenza medication developed by Fujifilm, to treat patients with COVID-19.[54][55]

Phase 2: Mitigation

On 23 February 2020, Abe instructed the government's coronavirus task force to quickly draft a comprehensive basic policy.[56] Health Minister Katsunobu Katō reconvened the medical experts from the first Novel Coronavirus Expert Meeting on 24 February 2020 to draft this policy.[57] During the meeting, the medical establishment presented its policy recommendations in the form of a views report (新型コロナウイルス感染症対策の基本方針の具体化に向けた見解), concluding that the most important objective must be the prevention of large-scale disease clusters and a decrease in outbreaks and deaths. They stated that it would not be possible for the government to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in Japan on a person-to-person basis, but that it might be possible to regulate the overall speed of infection.[58] They cited the next week or two as a "critical moment" determining whether the country would experience a large cluster that could result in the collapse of the medical system and socio-economic chaos. After reviewing and discussing the existing data on the disease, the committee stated that universal PCR testing was impossible due to a shortage of testing facilities and providers, and recommended that the government instead limit the application of available test kits to patients that are at a high risk of complications to stockpile for a large cluster. Participants also noted that Japan's medical facilities are vulnerable to "chaos," noting that many hospital beds and resources in the Tokyo area were already being used to care for the 700 infected patients from the Diamond Princess. They reiterated their warning that a rush of alarmed, uninfected outpatients with light symptoms of the disease could overwhelm hospitals and turn waiting rooms into "breeding grounds" for COVID-19.[59]

On 25 February 2020, the Abe Administration introduced the "Basic Policies for Novel Coronavirus Disease Control" (新型コロナウイルス感染症対策の基本方針) based on advice from the expert meeting.[60] After a spike of infections in Italy, Iran, and South Korea, Abe decided that the government's disease countermeasures would prioritize the prevention of large-scale clusters in Japan. This included controversial requests to suspend large-scale gatherings such as community events and school operations, as well as to limit patients with light cold symptoms from visiting medical facilities to prevent them from overwhelming hospital resources.[61]

First, the new policies advised local medical institutions that it is better for people with mild cold-like symptoms to rely on bed rest at home, rather than to seek medical help from clinics or hospitals. The policy also recommended that people at a higher risk of infection – including the elderly and patients with pre-existing conditions – avoid hospital visits for non-treatment purposes, such as by ordering prescriptions over the telephone instead of in person.[59]

Second, the new policies allowed general medical facilities in areas of a rapid COVID-19 outbreak to accept patients suspected of infection. Before this, patients could only get tested at specialized clinics after making an appointment with consultation centers to prevent the transmission of the disease. Government officials revised the previous policy after acknowledging that such specialized institutions would be overwhelmed during a large cluster.[59]

Third, the policy asked those with any cold symptoms to take time off from work and avoid leaving their homes. Government officials urged companies to let employees work from home and commute at off-peak hours. The Japanese government also made an official request to local governments and businesses to cancel large-scale events.[59]

On 27 February 2020, Abe requested the closure of all schools from 2 March 2020 to the end of spring vacations, which usually conclude in early April. The next day, the Japanese government announced plans to create a fund to help companies subsidize workers who need to take days off to look after their children while schools are closed.[62]

On 27 February 2020, the Japanese government also announced plans to expand the national health insurance system so that it covers COVID-19 tests.[63]

On 9 March 2020, the Ministry of Health reconvened the Expert Meeting after the two weeks "critical moment." The panel of medical experts concluded that Japan was currently not on track to experience a large-scale cluster, but stated that there was a two-week time lag in analyzing COVID-19 trends and that the country would continue to see more infections. Consequently, the participants asked the government to remain vigilant in quickly identifying and containing smaller clusters. With more COVID-19 outbreaks around the world, the panel also proposed that new infections from abroad could initiate a "second wave" of the disease in Japan.[64][65]

On 9 March 2020, the Health Ministry published a disease forecast for each prefecture and instructed local governments to prepare their hospitals to accommodate their patient estimates. It predicted that the virus peak in each prefecture would occur three months after the first reported case of local transmission. The Ministry estimated that at the peak Tokyo would see 45,400 outpatients and 20,500 inpatients per day, of whom 700 would be in severe condition. For Hokkaido, the figure was 18,300 outpatients and 10,200 inpatients daily, of whom about 340 would be severe.[66]

State of Emergency

On 5 February 2020, the Abe administration's coronavirus task force initiated a political debate on the introduction of emergency measures to combat the COVID-19 outbreak a day after the British cruise ship Diamond Princess was asked to quarantine. The initial debate focused on constitutional reform due to the task force's apprehension that the Japanese Constitution may restrict the government's ability to enact such compulsory measures as quarantines on the grounds that it violated human rights. After lawmakers representing almost all of the major political parties – including the Jimintō, Rikken-minshutō, and Kokumin-minshutō – voiced their strong opposition towards this proposal and asserted that the Constitution allowed for emergency measures, the Abe administration moved forward with legislative reform instead.[67]

On 5 March 2020, Abe introduced a draft amendment to the Special Measures Act to Counter New Types of Influenza of 2012 to extend the law's emergency measures for an influenza outbreak to include COVID-19. He met separately with the heads of five opposition parties on 4 March 2020 to promote a "united front" in passing the reforms. The National Diet passed the amendment on 13 March 2020, making it effective for the next two years.[68][69] The amendment allows the Prime Minister to declare a "state of emergency" in specific areas where COVID-19 poses a grave threat to the lives and economic livelihood of residents. During such a period, governors of affected areas will receive the following powers: (1) to instruct residents to avoid unnecessary outings unless they are workers in such essential services like health care and public transportation; (2) to restrict the use or request the temporary closure of businesses and facilities, including schools, social welfare facilities, theatres, music venues, and sports stadiums; (3) to expropriate private land and buildings to erect new hospitals; and (4) to requisition medical supplies and food from companies that refuse to sell them, punish those that hoard or do not comply, and force firms to help transport emergency goods.[70]

Under the law, the Japanese government does not have the authority to enforce citywide lockdowns. Apart from individual quarantine measures, officials cannot restrict the movement of people to contain the virus. Consequently, compliance with government requests to restrict movements is based on "asking for public cooperation to 'protect people's lives' and minimize further damage to [the economy]".[71]

On 25 March 2020, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare announced that the daily number of confirmed cases in Tokyo increased from 17 to 41 cases compared to the day before.[72] Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike held an emergency press conference in the late afternoon, stating that "the current situation is a serious situation where the number of infected people may explode." She requested residents to refrain from nonessential outings during the upcoming weekend.[73]

On 26 March 2020, the Ministry of Health reconvened the Novel Coronavirus Expert Meeting to review the new data. The panel of medical experts concluded that there was a "high probability of an expansion of infections" within the country due to an increase in the number of infected patients returning from Europe and the United States between 11 March 2020 and 23 March 2020.[4] In response to the statement, Abe instructed Economic Policy Minister Yasutoshi Nishimura to establish a special government task force to combat the spread of the virus.[74]

On 30 March 2020, Koike requested residents to refrain from nonessential outings for the next two weeks due to a continued increase in infections in Tokyo.[75] During a press conference held by the Japan Medical Association that same day, Kamayachi Satoshi of the government's panel of medical experts stated that his fellow panelists were divided over whether Abe should declare a state of emergency.[76]

On 1 April 2020, the Ministry of Health reconvened the Novel Coronavirus Expert Meeting to assess the current COVID-19 situation in Japan.[4]

On 2 April 2020, the Ministry of Health issued a notice that urged non-critical COVID-19 patients to move out of hospitals and stay at home or facilities designated by local governments.[77] Prefectural governors across the country began arranging accommodation for such patients through hotel operators and dormitories and issued official requests to the Japan Self-Defense Force for transportation services.[78][79]

On 3 April 2020, Professor Nishiura Hiroshi of the Ministry of Health's Cluster Response Team presented the initial findings of his COVID-19 epidemiological models to the public.[80] He concluded that the government could prevent an explosive spread of the virus in Japan if it adopted strict restrictions on outings that reduced social interactions by 80 percent, while such a spread would occur if the government adopted no measures or reduced social interactions by only 20 percent. Nishiura added that Tokyo was about 10 days to two weeks away from a large-scale outbreak.[81]

On 3 April 2020, at 12:00 am the travel ban would come into effect. The travel ban added 49 New countries that Japanese citizens couldn't travel too. Some of the main countries that were added were. China, The United States, Britain, Canada, Australia, and more. This puts Japan's country ban list to 73 total countries.[82]

On 7 April 2020, Abe proclaimed a one-month state of emergency from 8 April to 6 May for Tokyo and the prefectures of Kanagawa, Saitama, Chiba, Osaka, Hyogo and Fukuoka. This decision to go into a state of emergency was made by Abe and the Novel Coronavirus Response and Infection Protection task force. Due to the law that was first established in 2012 called the Influenza and New Infectious Disease Preparedness and Response Act.[83] He stated that the number of patients would peak in two weeks if the number of person-to-person contacts was reduced by 70 to 80 percent, and urged the public to stay at home to achieve this goal.

On 10 April 2020, Koike announced closure requests for six categories of businesses in Tokyo.[84] They include amusement facilities, universities and cram schools, sports and recreation facilities, theatres, event and exhibition venues. and commercial facilities. She also asked restaurants to limit opening hours to between 5 a.m. and 8 p.m. and to stop serving alcohol at 7 p.m. The request was to take effect on 12 April 2020 and promised government subsidies for businesses that cooperated with it.[citation needed]

On 11 April 2020, Professor Nishiura presented the remaining findings of his COVID-19 epidemiological models.[85][86] He determined that reducing social interactions by 80 percent would decrease the COVID-19 infection rate to a manageable level in 15 days; by 70 percent in 34 days; by 65 percent in 70 days; and by 50 percent in three months. Any rate below 60 percent would increase the number of cases.

On 16 April 2020, Abe expanded the state of emergency declaration to include every prefecture within the country.[16] On 4 May, Abe said that the state of emergency would be extended until the end of the month.[87] On 14 May, the government lifted the state of emergency in all but eight high-risk prefectures including Tokyo and Kyoto.[88]

On 21 May 2020, the state of emergency was lifted in three prefectures in Kansai after they reported an infection rate below 0.5 per 100,000 people in the past week; only five of 47 prefectures remained under the state of emergency.[89][90]

Novel Coronavirus Expert Meeting

On 16 February 2020, Abe convened the Novel Coronavirus Expert Meeting to incorporate members of the Japanese medical community into his decision-making process.[49] The panel acts as the main medical advisory body of the Japanese government during the COVID-19 crisis.[91]

Chair

- Wakita Takaji (Director-General of the NIID)

Vice Chair

- Omi Shigeru (President of the Japan Community Health Care Organization)

Members

- Okabe Nobuhiko (Director of the Kawasaki Municipal Institute of Public Health)

- Hitoshi Oshitani (Former Infectious Disease Control Advisor at the WHO Western Pacific Regional Office)

- Kamayachi Satoshi (Executive Board Member of the Japan Medical Association)

- Kawaoka Yoshihiro (Professor of Virology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and University of Tokyo)

- Kawana Akihiko (Professor of Internal Medicine at the National Defense Medical College)

- Suzuki Motoi (Director of the NIID Center of Infectious Disease Epidemiology)

- Tateda Kazuhiro (Professor of Microbiology and Infectious Disease at Toho University)

- Nakayama Hitomi (Social Worker and Lawyer at the Kasumigaseki-Sogo Law Offices)

- Muto Kaori (Professor of Cultural and Human Information Studies at the University of Tokyo)

- Yoshida Masaki (Professor of Internal Medicine at Jikei University School of Medicine)

Support measures

On 12 February 2020, Abe announced that the government would secure 500 billion yen for emergency lending and loan guarantees to small and medium enterprises affected by the COVID-19 outbreak.[92] He also declared that his Cabinet would set aside 15.3 billion yen from contingency funds to facilitate the donation of isolated virus samples to relevant research institutions across the globe.[93]

On 1 March 2020, Abe evoked the Act on Emergency Measures for Stabilizing Living Conditions of the Public to regulate the sale and distribution of facial masks in Hokkaido. Under this policy, the Japanese government instructed manufacturers to sell facial masks directly to the government, which would then deliver them to residents.[38] On 5 March 2020, the Japanese government announced that it is organizing an emergency package by using a 270 billion yen ($2.5 billion) reserve fund for the current fiscal year through March to contain the virus and minimize its impact on the economy.[94]

Three Cs (3つの密, Mittsu no Mitsu, "Three 'Close's"), also written Three C's or 3密 (San Mitsu), is a slogan originated by the Japanese government in 2020 in combating the COVID-19 pandemic.[95] The Three Cs were announced by the office of the Prime Minister of Japan on Twitter on 17 March 2020.[96] This followed work by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare on how to prevent superspreader events and other clusters (クラスター), including the 25 February 2020 establishment of a Cluster Countermeasures Group within the ministry.[97] The slogan warns people to avoid three factors that contribute to clusters of infection:[98] Closed spaces (密閉) with poor ventilation; Crowded places (密集) with many people nearby; and Close-contact settings (密接) such as close-range conversations. On 16 July 2020, the WHO posted a recommendation to "Avoid the Three Cs", in terms very similar to those used in English by the Japanese government.[99]

Controversies and criticism

On 17 February 2020, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare asked that those who have experienced fever over 37.5 °C for more than four days, in addition to those who experience severe symptoms such as lethargy and difficulty breathing, consult with the Return and Contact Consultation Centres immediately to determine whether testing is required.[100][101] However, some media outlets asserted that restrictive standards for testing would delay public health response to the pandemic, resulting in further spread of the disease.[102][103]

In early February, Masahiro Kami, a hematologist, chairman of the Institute for Healthcare Governance, and outside director of SBI Pharma Co., Ltd. and SBI Biotech Co., Ltd., criticized Japan's response to outbreaks of the disease onboard isolated cruise ships compared to that of Italy.[104]

In late February, several Japanese media outlets reported that there were people with fever or other symptoms who could not be tested through the consultation centre system and had become "test refugees" (検査難民).[105][106][107][108] Some of these cases involved patients with severe pneumonia.[109] Hematologist Masahiro Kami claimed that many patients were denied testing due to their mild symptoms and criticized the Japanese government for setting testing standards that were too high and for lacking a response to patient anxiety.[110]

On 26 February 2020, Minister of Health Katsunobu Kato stated in the National Diet that 6,300 samples were tested between 18 and 24 February, averaging 900 samples per day. Some representatives questioned the discrepancy between the actual number of people tested and the claim in the prior week that 3,800 samples could be tested per day.[111]

On the same day, more doctors reported that public health centers had refused to test some patients. The Japan Medical Association announced that it would start a nationwide investigation and plan to cooperate with the government to improve the situation.[112] The Ministry of Health also stated that it would look into the situation with the local governments.[113]

The strict constraints on testing for the virus by Japanese health authorities drew accusations from critics such as Masahiro Kami that Abe wanted to "downplay the number of infections or patients because of the upcoming Olympics." It was reported that only a few public health facilities were authorized to test for the virus, after which the results could only be processed by five government-approved companies, which created a bottleneck forcing clinics to turn away even patients with high fevers. This has led some experts to question Japan's official case numbers. For example, Tobias Harris, of Teneo Intelligence in Washington, D.C., said: "You wonder, if they were testing nearly as much as South Korea is testing, what would the actual number be? How many cases are lurking and justare not being caught?"[102][114] Fact-checking in several media later proved that the news that the government had reduced the number of tests to curb the increase in the number of infected people for the Olympics was not accurate at all.[115][116]

Testing was still restricted to large hospitals in March 2020, with 52,000 tests, or 16% of the South Korean amount, performed that month. A decision to expand testing was made on 13 April 2020.[117] There were many articles in March that criticized the number of PCR tests in Japan as very small compared to South Korea.[118][119] According to data released by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japanese authorities conducted a total of 15,655 PCR tests as of 17 March 2020, excluding tests conducted on those returning from China by charter flights and passengers on cruise ships.[120][121][122] Many hospitals were running out of resources and were turning away patients due to lack of equipment to deal with them. Despite having more hospital beds per head than any other country, they didn't have enough tests or equipment to care for patients with respiratory diseases. Hospitals had beds for patients but they couldn't be classed as infectious disease beds because they didn't have the respiratory equipment to be able to be used.[123]

On 5 March 2020, Japan announced that it will strengthen quarantine for new entrants from China and South Korea, along with added areas of Iran to the target area. The Chinese government showed understanding for the decision, while the Korean government called the measures implemented by Japan "unreasonable and excessive."[124][125][126][127][128]

The government's distribution of cloth masks was criticized for poor budgeting and lack of quality in the masks.[129][130] One of the companies involved in mask production was accused of being a ghost company.[129][130][131] Some companies whose mask production was critiqued in the media, as well as personnel associated with those companies, experienced harassment on social media and in person.[132][133][134]

The new method introduced by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare will count fewer COVID patients, and has resulted in bringing the numbers down the in numerous prefectures.[135][136]

Medical response

The medical task-force advising the government, known as the Novel Coronavirus Expert Meeting, has adopted a three-pronged strategy to contain and mitigate COVID-19 that includes: (1) early detection of and early response to clusters through contact tracing; (2) early patient diagnosis and enhancement of intensive care and the securing of a medical service system for the severely ill; and (3) behavior modification of citizens.[137] Medical experts have prioritized COVID-19 testing for the first two purposes while relying on the behavior modification of citizens rather than mass testing to prevent the spread of the virus at a large-scale level.[138]

Contact tracing

On 25 February 2020, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare established the Cluster Response Team (クラスター対策班) in accordance with the Basic Policies for Novel Coronavirus Disease Control.[139] The purpose of the section is to identify and contain small-scale clusters of COVID-19 infections before they grow into mega-clusters. It is led by university professors Hitoshi Oshitani and Nishiura Hiroshi and consists of a contact tracing team and a surveillance team from the National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID), a data analysis team from Hokkaido University, a risk management team from Tohoku University, and an administration team.[140] Whenever a local government determines the existence of a cluster from hospital reports, the Ministry of Health dispatches the section to the area to conduct an epidemiological survey and contact tracing in coordination with members of the local public health center. After the teams determine the source of infection, the ministry and local government officials enact countermeasures to locate, test, and place under medical surveillance anybody who may have come into contact with an infected person. They can also file requests to suspend infected businesses or restrict events from taking place there.[140]

From its contract tracing findings, the Ministry of Health discovered that 80% of infected people did not transmit COVID-19 to another person. The Ministry also determined that patients that did infect another person tended to spread it to multiple people and form infection clusters when they were in certain environments.[141] According to one of the experts, Kawaoka Yoshihiro, "[This meant that] you don't need to trace every single person who's been infected if you can trace the cluster. If you do nothing, the cluster will grow out of control. But as long as you identify a cluster small enough to contain, then the virus will die out."[142]

On 9 March 2020, the medical experts reviewed the data from the Cluster Response Team's work and further refined its definition of a high-risk environment as a place with the overlapping "three Cs" (three close-contact situations (三つの密, mittsu no mitsu)): (1) closed spaces with poor ventilation; (2) crowded places with many people nearby; and (3) close-contact settings such as close-range conversations.[143] They identified gyms, live music clubs, exhibition conferences, social gatherings, and yakatabune as examples of such places. The experts also theorized that crowded trains did not form clusters because people riding public transportation in Japan usually do not engage in conversations.[143]

During times when the number of infected patients rises to such an extent that individual contract tracing alone cannot contain a COVID-19 outbreak, the government will request the broad closure of such high-risk businesses.[144]

During the initial stages of the outbreak, medical experts recommended the government to focus on COVID-19 testing for contact tracing purposes and patients with the following symptoms: (1) cold symptoms and a fever of at least 37.5 °C (or need to take antipyretic medication) for over four days; and (2) extreme fatigue and breathing difficulties.[53] The elderly, people with pre-existing conditions, and pregnant women with cold symptoms could be tested if they had them for two days.[53][52] The country's high number of computed tomography (CT) scanners (111.49 per million people) allows them to confirm suspicious pneumonia cases and begin treatment before testing them for COVID-19.[citation needed]

On 1 April 2020, medical experts requested the government to secure more hospital beds for patients and transfer those with mild or no symptoms to outside housing facilities to focus treatment on the severely-ill.[4]

Behavior modification of citizens

The Japanese government's medical task-force anticipates multiple waves of COVID-19 to arrive in the country for at least the next three years, with each one prompting the public to engage in a cycle of restricting and easing movement.[142] Under the current law, the Prime Minister can restrict movement by declaring a "state of emergency" in specific areas where COVID-19 poses a grave threat to residents. During such periods, the governors of affected areas can request citizens to avoid unnecessary outings and temporarily close certain businesses and facilities. Since the government cannot enact compulsory measures to enforce these requests, it has instead embarked on a social engineering program to train its citizens to comply with them on a voluntary basis during current and future state of emergencies.[142]

To reduce person-to-person contact, the government has instructed the public to refrain from going to high-risk environments (the Three Cs: closed spaces, crowded places, and close-contact settings) and events involving movement between different areas of the country.[144] It emphasized extreme caution when coming in contact with the elderly. The government also promoted such work-style reforms as remote work and staggering commuting hours, while improving the country's distance learning infrastructure for children.[144]

On 4 May 2020, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare unveiled its program to create a "new lifestyle" (新しい生活様式) for the country's citizenry that is to be practiced every day on a long-term basis.[145][146] Several elements of the lifestyle include behavior changes demanded under the state of emergency, such as avoiding high-risk environments and long-distance travelling. However, the program expands these precautions to cover more mundane activities by requesting people to engage in such activities as wearing masks during all conversations, refraining from talking when using public transportation, and eating next to one another rather than facing one another.[144][145]

Vaccination

COVID-19 vaccination in Japan started later than in most other major economies.[148] The country has frequently been regarded as "slow" in its vaccination efforts.[149][150]

Japan has so far approved Pfizer–BioNTech, Moderna and Oxford–AstraZeneca for use. In April 2024, data from the government shows that 79.5% of people have had their second dose, while 80.4% have received first shot.[151] Today, 79 percent of Japanese people have received two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine; 67 percent have received a third (booster) dose.[152]Regional developments

The following are examples of the spread of infections for five of the eight regions in Japan.

Hokkaido

The first case was identified in Hokkaido on 28 January 2020,[153][154] and the second case was confirmed on 14 February 2020.[153][155] To limit the spread of infection, the governor of Hokkaido, Naomichi Suzuki, announced the Declaration of a New Coronavirus Emergency on 28 February 2020, calling on locals to refrain from going out.[156]

Tōhoku

The Tōhoku region had been relatively unaffected during the earlier waves of infections. As late as 10 July 2020, Iwate Prefecture had not reported any cases.[157] By 3 April 2021, the total number of reported COVID-19 cases in the region had reached 12,076, with 6,423 of those cases having been reported in Miyagi Prefecture, 4,196 of which were from the city of Sendai.[158][159][160][161][162][163]

Chūbu

The first case was identified in Aichi Prefecture on 26 January 2020,[164] and the second was identified on 14 February 2020.[164] As the virus spread, the prefectural governor Omura stated that there were two major groups of infected people in Aichi, centred in Nagoya. He emphasized the need for collaboration between the national, prefectural, and city governments to prevent the spread of the virus.[165]

Kansai

The Osaka model (Japanese: 大阪モデル, Hepburn: Ōsaka moderu) of self-restraint (自粛, Jishuku) was widely praised in Japan.[166] The proactive measures enacted by Governor Yoshimura in Osaka Prefecture have been effective in mitigating the effects of the pandemic compared to other regions of Japan with minimal disruptions to education or the economy. Governors of other prefectures have followed this example. As the second-largest population center in Japan with the highest population density in the Kansai region, this has been effective to reduce the spread of the virus in this region. Reduced international tourism to Kyoto due to travel restrictions and cancellations of tour groups has also reduced the spread of the virus but the tourism sector is struggling as a result.[167][168]

Kyushu

On 24 May 2020, Fukuoka Prefecture announced a total of four confirmed cases, including one re-positive case confirmed in Fukuoka City, and three in Kitakyushu City.[169] On 2 July 2020, Kagoshima City confirmed a cluster of nine new cases of COVID-19, and Fukuoka Prefecture confirmed four.[170]

Socio-economic impact

Abe said that "the new coronavirus is having a major impact on tourism, the economy and our society as a whole",[171][172] throwing Japan into a recession. In Q1 2020 GDP there was 0.9 contraction, whereas in Q4 2019 GDP there was 1.9 contraction.[173] During the early stages of the pandemic, face masks sold out across the nation and new stocks were quickly depleted.[174] Pressure was placed on the healthcare system as demands for medical checkups increased.[175] Chinese people were reported to have suffered increased discrimination.[176]

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, logistics and supply chains from Chinese factories were disrupted, leading to complaints from certain Japanese manufacturers.[177] Abe considered using emergency funds to mitigate the outbreak's impact on tourism, 40% of which is by Chinese nationals.[178] S&P Global noted that the worst-hit stocks were for travel, cosmetics and retail companies, which are most exposed to Chinese tourism.[179] Video game developer Nintendo issued a statement apologizing for delays in shipments of Nintendo Switch hardware, attributing it to the coronavirus outbreak in China, where much of the company's manufacturing is located.[180] On the same day the Nagoya Expressway Public Corporation announced plans to temporarily close some toll gates and let employees work from their homes after an employee staffing the toll gates was diagnosed positive for SARS-CoV-2.[181] Due to personnel shortages, six toll gates on the Tōkai and Manba routes of the expressway network were closed over the following weekend.[181]

In September 2020, the central government declared its intent to encourage remote work from the country's rural areas to combat the spread of the virus by subsidizing municipalities outside of the Greater Tokyo Area a total of ¥15 billion.[182] The remote work subsidy was made available to eligible municipalities at the onset of FY 2021 on 1 April 2021.[183]

Sporting events

The outbreak affected professional sports in Japan. Nippon Professional Baseball's preseason games and the Haru Basho sumo tournament in Osaka were to be held behind closed doors, while the J.League football and Top League rugby suspended or postponed play entirely.[184] On the weekend of 29 February 2020, the Japan Racing Association closed its horse racing meets to spectators and off-track betting until further notice, but continued to offer wagering by phone and online.[185]

The outbreak affected school sports in Japan. Health concerns led to sporting events such as baseball, basketball, and soccer in school being suspended or postponed, due to unexpected postponement of education generally.[citation needed]

Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics

The expansion of COVID-19 into a global pandemic led to concerns over the 2020 Summer Olympics and Paralympics in Tokyo, which continue to this day. In March 2020, it was announced that the Games would be postponed by a year, for the first time in the history of the modern Olympics.[186][187] The Tokyo Olympics took place from 23 July to 8 August 2021.

There were 71 cases linked to the 2020 Summer Olympics since 17 July 2021.[188] The Tokyo Olympics triggered a massive surge in new cases in Japan.

Entertainment

On 26 February 2020, Abe suggested that major sporting, cultural and other events should be cancelled, delayed or scaled down for about two weeks amid the COVID-19 pandemic.[189] As a result, J-pop groups Perfume and Exile cancelled their series of concerts scheduled for that days at the Tokyo Dome and Kyocera Dome Osaka, respectively, both of which have a capacity of 55,000.[190] On 27 February 2020, AnimeJapan 2020, originally scheduled to be held in Tokyo Big Sight in late March, was cancelled.[191]

A number of major amusement parks had temporary closures beginning in February 2022. Some attractions partially reopened in March 2020, including Huis Ten Bosch and Legoland Japan Resort.[192][193] Tokyo Disneyland, Tokyo DisneySea and Tokyo Disney Resort were closed from 29 February 2020 to July 2020.[194][195][196] Universal Studios Japan closed from 29 February to June 8.[197][198]

Japanese comedian Ken Shimura died on 29 March 2020 at the age of 70.[199][200]

Beginning in March 2020, many Japanese animated films and TV shows announced changes or postponed broadcasts due to production problems resulting from a shortage of outsourced staff.[201][202] Beginning in May 2020, production of live-action and animated series were scaled back significantly to prevent the spread of infection. Multiple series across numerous channels were delayed or postponed, and most television channels resorted to broadcasting reruns.[203][204][205][206][207]

Festivals and contests

The following major festivals were cancelled: The triangle mark (△) would be cancelled in 2020 and 2021. The small circle mark (◌) cancelled on 2020, held on reduced scale on 2021.

|

|

The following major fireworks events were also canceled or considered to be postponed:The triangle mark (△) will be cancelled on 2020 and 2021

|

|

The following festivals were postponed:

- 2020 Sanja Matsuri Festival (三社祭), originally scheduled for 15–17 May, was changed to October in Tokyo[218]

- 2020 Japan Tree-planting Festival (全国植樹祭) in Shimane Prefecture, originally scheduled for 31 May 2020, was converted to online event held on May 30, 2021.[citation needed]

- 2020 Tohoku Kizuna Traditional Festival (東北絆祭り) in Yamagata City, originally schedule date for May 30 and 31, was changed to 22. 23 July 2021.[citation needed]

- 2020 Tochigi Autumn Traditional Festival (ja:とちぎ秋まつり), which held once per twice years in Tochigi City, originally schedule on November 6 to 7, that postpone to October or November 2021.[citation needed]

- 2021 Kofu Shingen Takeda Festival, original scheduled on early April, which postponement to November 2021.[citation needed]

The following major contests were canceled or postponed indefinitely:

- All Japan Kokeshi contest and exhibition in Shiroishi, Miyagi Prefecture

- All Japan chindonya contest in Toyama City

- Fukiage beach sand sculpture contest and exhibition in Minamisatsuma, Kagoshima Prefecture[citation needed]

- Arida Pottery Market in Saga Prefecture, originally scheduled for 29 April to 5 May, has been postponed indefinitely[citation needed]

- Daidogei World Cup in Shizuoka City, original schedule date on October 31 to November 3.[citation needed]

- Hikone Yuru-chara Festival, originally schedule held date November 6 and 7, Hikone Castle Park, Shiga Prefecture.[citation needed]

- 2021 World Masters Games, held in Kansai area, original schedule on May 14 to 30, which new schedule is indefinitely.[citation needed]

- According to Imperial Household Aagncy official confirmed report, the general public visit to Imperial New Year's event was cancelled in Imperial Palace in Tokyo, originally schedule date on January 2 on every year.[citation needed]

The following year-end and year-in countdown event place were cancelled:

- Shibuya Scramble Scuare in Tokyo

- Tokyo Disneyland, Tokyo Disneysea and Tokyo Disney Resort in Urayasu, Chiba Prefecture

- Nagashima Spa Land and Nabana village in Kuwana, Mie Prefecture.

- Universal Studios Japan in Osaka.

- Nima Sand Museum in Shimane Prefecture.

- Huis Ten Bosch in Sasebo, Nagasaki Prefecture.[citation needed]

Distance learning

On 27 February 2020, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe requested that all Japanese elementary, junior high, and high schools close until early April to help contain the virus.[6][219] Several days prior, the education board of Hokkaido had announced the temporary closure of the schools in the prefecture.[220] As of 5 March, 18,923 municipal elementary schools, 98.8 percent of those in Japan, had complied with Abe's request.[221] Subsequent analysis found that these school closures did not meaningfully contribute to a reduction in COVID-19 spread.[222]

Aid to China

On 26 January 2020, Japanese people donated a batch of face masks to Wuhan.[223] According to the Liberty Times of Taiwan, these were actually purchased by China,[224] but Japanese media and the Japanese Consulate General in Chongqing stated that it was a donation.[225][226]

On 3 February 2020, four organizations, the Japan Pharmaceutical NPO Corporation, the Japan Hubei Federation, Huobi Global, and Incuba Alpha, donated materials to Hubei.[227]

On 10 February 2020, the Liberal Democratic Party's Secretary-General Toshihiro Nikai said that the party would deduct 5,000 yen from the March funds from members of the party to support mainland China.[228]

Other

Between April and September 2020, restaurants accounted for 10% of all bankruptcies in Japan.[229] Ramen restaurants were particularly affected, with 34 chains filing for bankruptcy by September. Ramen restaurants are typically narrow and seat customers closely, making social distancing difficult.[229]

The pandemic seems to be the reason for the abrupt end to the slowly declining trend in suicides in Japan for the preceding 10 years. Since July 2020 their number increased significantly to record highs. Women bear the major part of this increase.[230]

Variants

Wild type SARS-CoV-2 was the virus that first arrived in Japan. From February through June 2020, B.1.1 was the main variant found in Japan.[231] From the end of June until mid-February, B.1.1.214 took over. In February and March, R.1 became common, but other variants were surpassing it by late June. Then around mid-March, the Alpha variant became dominant, and has been since. Now, Delta numbers seem to be rapidly rising. Alpha is believed to be more transmissible than wild type Sars-Cov-2, and may be more deadly. Delta is believed to be even more transmissible than Alpha. Identifying a sample as Delta requires full genome sequencing which is expensive and time-consuming, so the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has been using the presence of the L452R mutation as a shorthand way of tracking probable Delta cases.[232]

| Cumulative # of cases of variants (as of 17 July 2021) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | R.1 | L452R including Delta | Delta |

| 30,448[233] | 7,057[233] | 2,450[232] | 918[233] |

International travel restrictions

Restrictions on entry to Japan

On 3 April 2020, foreign travelers who had been in any of the following countries and regions within the past 14 days were barred from entering Japan. This travel ban covers all foreign nationals, including those holding Permanent Resident status. Foreign nationals with Special Permanent Resident status are not subject to immigration control under Article 5 of the Immigration Control Act 1951 and are therefore exempt.[234]

Japanese citizens and holders of Special Permanent Resident status may return to Japan from these countries but must undergo quarantine upon arrival until testing negative for COVID-19. On 11 October 2022, Japan reopened itself to non-citizens.[235]

Restrictions on entry from Japan

The following countries and territories have restricted entry from Japan:[236]

Algeria

Algeria Angola

Angola Antigua and Barbuda

Antigua and Barbuda Argentina: Flight suspension and suspension of all visas.[237][238]

Argentina: Flight suspension and suspension of all visas.[237][238] Armenia

Armenia Australia

Australia Austria

Austria Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan Bahamas

Bahamas Bahrain[3]

Bahrain[3] Bangladesh

Bangladesh Belgium

Belgium Belize

Belize Bhutan

Bhutan Bolivia

Bolivia Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina Botswana

Botswana Brazil

Brazil Brunei

Brunei Bulgaria

Bulgaria Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso Burundi

Burundi Cameroon

Cameroon Canada

Canada Cape Verde

Cape Verde Chad

Chad Chile

Chile China

China Colombia

Colombia Comoros[239]

Comoros[239] Cook Islands[3]

Cook Islands[3] Costa Rica

Costa Rica Croatia

Croatia Cuba

Cuba Cyprus

Cyprus Czech Republic

Czech Republic Democratic Republic of the Congo

Democratic Republic of the Congo Denmark

Denmark Dominica

Dominica Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Djibouti

Djibouti East Timor

East Timor Ecuador

Ecuador Egypt

Egypt El Salvador

El Salvador Equatorial Guinea

Equatorial Guinea Eritrea

Eritrea Estonia

Estonia Eswatini

Eswatini Ethiopia

Ethiopia Finland

Finland France

France French Polynesia[3]

French Polynesia[3] Gabon

Gabon Gambia

Gambia Georgia

Georgia Germany

Germany Ghana

Ghana Gibraltar

Gibraltar Greece

Greece Grenada

Grenada Guatemala

Guatemala Guinea

Guinea Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau Guyana

Guyana Haiti

Haiti- Honduras

Hong Kong

Hong Kong Hungary

Hungary Iceland

Iceland India[240]

India[240] Indonesia

Indonesia Iraq[240]

Iraq[240] Israel[240]

Israel[240] Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast Jamaica

Jamaica Jordan

Jordan Kazakhstan[241]

Kazakhstan[241] Kenya

Kenya Kiribati[239]

Kiribati[239] Kosovo

Kosovo Kuwait[240]

Kuwait[240] Kyrgyzstan[240]

Kyrgyzstan[240] Laos

Laos Latvia

Latvia Lebanon

Lebanon Liberia

Liberia Libya

Libya Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein Lithuania

Lithuania Luxembourg

Luxembourg Macau

Macau Macedonia

Macedonia Madagascar

Madagascar Marshall Islands[240]

Marshall Islands[240] Malawi

Malawi Malaysia

Malaysia Maldives

Maldives Mali

Mali Malta

Malta Mauritania

Mauritania Mauritius

Mauritius Micronesia[240]

Micronesia[240] Moldova

Moldova Mongolia[240]

Mongolia[240] Montenegro

Montenegro Morocco

Morocco Mozambique

Mozambique Myanmar

Myanmar Namibia

Namibia Nauru

Nauru Nepal

Nepal Netherlands

Netherlands New Caledonia

New Caledonia New Zealand

New Zealand Niger

Niger Nigeria[242]

Nigeria[242] Niue

Niue Norway

Norway Oman

Oman Pakistan

Pakistan Panama

Panama Papua New Guinea[243]

Papua New Guinea[243] Paraguay

Paraguay Peru

Peru Philippines

Philippines Poland

Poland Portugal

Portugal Qatar

Qatar Republic of the Congo

Republic of the Congo Romania

Romania Russia

Russia Rwanda

Rwanda Saint Kitts and Nevis

Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia[244]

Saint Lucia[244] Saint Vincent and the Grenadines[244]

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines[244] Samoa[239]

Samoa[239] Sao Tome and Principe

Sao Tome and Principe Saudi Arabia[240]

Saudi Arabia[240] Senegal

Senegal Serbia

Serbia Seychelles

Seychelles Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone Singapore

Singapore Sint Maarten[244]

Sint Maarten[244] Slovakia

Slovakia Slovenia

Slovenia Somalia

Somalia Solomon Islands[239]

Solomon Islands[239] South Africa

South Africa South Korea

South Korea South Sudan

South Sudan Spain

Spain Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka Sudan

Sudan Suriname

Suriname Sweden

Sweden Switzerland

Switzerland Syria

Syria Taiwan

Taiwan Tajikistan[245]

Tajikistan[245] Thailand

Thailand Togo

Togo Tonga

Tonga Trinidad and Tobago[240]

Trinidad and Tobago[240] Tunisia

Tunisia Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan Tuvalu[239]

Tuvalu[239] Uganda

Uganda Ukraine

Ukraine United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates Uruguay

Uruguay Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan Vanuatu[240]

Vanuatu[240] Venezuela

Venezuela Vietnam

Vietnam Yemen

Yemen Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

Japan to downgrade coronavirus classification

The government of Japan has formally decided to downgrade from May 8, 2023, the legal status of the novel coronavirus to the same category as common infectious diseases, such as seasonal influenza, to ease COVID-19 prevention rules.[246]

See also

- COVID-19 pandemic in Tokyo

- COVID-19 pandemic in Asia

- COVID-19 pandemic by country

- Deployment of COVID-19 vaccines

- COVID-19 pandemic death rates by country

- 2020 in Japan

- 2021 in Japan

- National responses to the COVID-19 pandemic

- Healthcare in Japan

- Nursing in Japan

- Aging of Japan

- COVID-19 outbreak at the 2020 Summer Olympics

Notes

- ^ The Kuril Islands are administered by Russia, six cases have been reported in the Sakhalin Oblast overall.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Mathieu E, Ritchie H, Rodés-Guirao L, Appel C, Giattino C, Hasell J, Macdonald B, Dattani S, Beltekian D, Ortiz-Ospina E, Roser M (2020–2024). "Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)". Our World in Data. Retrieved 13 January 2025.

- ^ "COVID - Coronavirus Statistics - Worldometer".

- ^ a b c d e "新型コロナウイルスに関連した肺炎の患者の発生について(1例目)" (in Japanese). 16 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Expert Meeting on Control of the Novel Coronavirus Disease Control" (PDF). mhlw.go.jp. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 1 April 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ a b Hasan SM, Saulam J, Kanda K, Ngatu NR, Hirao T (30 June 2020). "Trends in COVID-19 outbreak in Tokyo and Osaka from January 25 to May 06, 2020: a joinpoint regression analysis of the outbreak data". Jpn J Infect Dis. 74 (1): 73–75. doi:10.7883/yoken.JJID.2020.332. PMID 32611984. S2CID 220304131.

- ^ a b c d "国内のコロナ、武漢ではなく欧州から伝播? 感染研調べ:朝日新聞デジタル" [Domestic corona, propagation from Europe instead of Wuhan? Infectious disease research]. 朝日新聞デジタル (in Japanese). The Asahi Shimbun Digital. 28 April 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Haplotype networks of SARS-CoV-2 infections". National Institute of Infectious Diseases. 16 April 2020. Archived from the original on 28 April 2020.

- ^ Medina-Pérez DN, Wager B, Troy E, Gao L, Norris SJ, Lin T, Hu L, Hyde JA, Lybecker M, Skare JT (4 May 2020). "The intergenic small non-coding RNA ittA is required for optimal infectivity and tissue tropism in Borrelia burgdorferi". PLOS Pathogens. 16 (5): e1008423. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1008423. ISSN 1553-7374. PMC 7224557. PMID 32365143.

- ^ a b 新型コロナウイルス感染症の現在の状況と厚生労働省の対応について(令和2年12月31日版) (in Japanese). Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. 31 December 2020. Archived from the original on 9 October 2024. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- ^ Lipscy PY (2023), Pekkanen RJ, Reed SR, Smith DM (eds.), "Japan's Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic", Japan Decides 2021: The Japanese General Election, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 239–254, doi:10.1007/978-3-031-11324-6_16, ISBN 978-3-031-11324-6, retrieved 27 May 2024

- ^ "The Independent Investigation Commission on the Japanese Government's Response to COVID-19". Asia Pacific Initiative アジア・パシフィック・イニシアティブ. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Novel Coronavirus Response Headquarters". Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet. 30 January 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ Thorn A (June 2020). "Die Coronavirus Structural Task Force". BIOspektrum. 26 (4): 442–443. doi:10.1007/s12268-020-1408-0. ISSN 0947-0867. PMC 7318718. PMID 32834542.

- ^ "PM Abe asks all schools in Japan to temporarily close over coronavirus". Kyodo News.

- ^ Reynolds I, Nobuhiro E (7 April 2020). "Japan Declares Emergency For Tokyo, Osaka as Hospitals Fill Up". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Japan PM Abe declares nationwide state of emergency amid virus spread". Mainichi Shimbun. 16 April 2020. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ Kyodo News (25 May 2020). "Abe declares coronavirus emergency over in Japan".

- ^ Helen Regan, Junko Ogura (8 January 2021). "Japan's Suga declares state of emergency for Tokyo as Covid-19 cases reach highest levels". CNN.

- ^ Iwasaki A, Grubaugh ND (2020). "Why does Japan have so few cases of COVID-19?". EMBO Molecular Medicine. 12 (5): e12481. doi:10.15252/emmm.202012481. PMC 7207161. PMID 32275804.

- ^ "死亡数、コロナ余波で急増 震災の11年上回るペース". Nikkei. 10 December 2021. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ "Tokyo 2020 Olympics officially postponed until 2021". ESPN. 24 March 2020.

- ^ Ostlere L (6 August 2021). "Olympics full schedule: Tokyo 2020 day-by-day events, dates, times and venues". The Independent. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ a b 新型コロナウイルス感染症の現在の状況と厚生労働省の対応について(令和3年12月31日版) (in Japanese). Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. 31 December 2021. Archived from the original on 27 February 2024. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- ^ a b 新型コロナウイルス感染症の現在の状況について(令和4年12月31日版) (in Japanese). Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. 31 December 2022. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- ^ a b 【詳しく】新型コロナ 5月8日から「5類」に移行 何が変わる (in Japanese). 8 May 2023. Archived from the original on 13 January 2024. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- ^ a b 新型コロナウイルス感染症の現在の状況について(令和5年5月8日版) (in Japanese). Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. 8 May 2023. Archived from the original on 26 November 2024. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- ^ 国立感染症研究所 (NIID) (27 April 2020). "新型コロナウイルス SARS-CoV-2 のゲノム分⼦疫学調査" (PDF).

- ^ a b The Yomiuri Shimbun. "Virus strain in Japan possibly spread via Europe, U.S. since March". the-japan-news.com. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "WHO | Novel Coronavirus – Japan (ex-China)". WHO. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ^ Walter S (16 January 2020). "Japan confirms first case of infection from Wuhan coronavirus; Vietnam quarantines two tourists". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 16 January 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ Virus strain in Japan possibly spread via Europe, U.S. since March. The Japan News (29 April 2020).Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare

- ^ a b "Second Meeting of the Novel Coronavirus Response Headquarters". Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet, 31 January 2020.

- ^ "Ministerial Meeting on Countermeasures Related to the Novel Coronavirus". Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet.

- ^ a b "Japan will label coronavirus as infectious disease to fight spread". The Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ "Shinzo ABE (The Cabinet) | Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet". japan.kantei.go.jp. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ "Competing with Authoritarianism: Deputy Chief Cabinet Secretary Kihara Seiji Talks Policy (Part 2)". nippon.com. 14 July 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Fourth Meeting of the Novel Coronavirus Response Headquarters". Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet, 1 February 2020.

- ^ "Japan expands entry restrictions to virus-hit Zhejiang". Nikkei Asian Review. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Fifth Meeting of the Novel Coronavirus Response Headquarters". Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet. 5 February 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ [Sixth Meeting of the Novel Coronavirus Response Headquarters "Sixth Meeting of the Novel Coronavirus Response Headquarters", Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet, 6 February 2020]

- ^ a b 新型肺炎「帰国者・接触者相談センター」設置へ 専門外来への受診を促す. Mainichi Shimbun (in Japanese). 3 February 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ "Seventh Meeting of the Novel Coronavirus Response Headquarters". Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet, 12 February 2020.

- ^ "Japan, alarmed by new cases, to expand, speed up coronavirus tests". The Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ SRL (12 February 2020). 新型コロナウイルス検査の受託について (PDF).

- ^ "Corporate Japan rushes to devise quick coronavirus tests". Nikkei Asian Review. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ "Ninth Meeting of the Novel Coronavirus Response Headquarters". Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet, 14 February 2020.

- ^ 新型コロナウイルスに関する帰国者・接触者相談センター. Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. 13 February 2020.

- ^ a b 新型コロナウイルス感染症対策専門家会議の開催について (On the Opening of the First Novel Coronavirus Expert Meeting) (PDF). Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet. 14 February 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ Saitō, Katsuhisa (19 February 2020) "Early Stage of a Japan Outbreak: The Policies Needed to Support Coronavirus Patients". Nippon.com.

- ^ "First Novel Coronavirus Expert Meeting". Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet, 19 February 2020.

- ^ a b c "Prevention Measures against Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)" (PDF). 厚生労働省. Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. 25 February 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ a b c 新型コロナウイルス感染症についての相談・受診の目安について (Criterion for Consultation and Medical Examination concerning the Novel Coronavirus Disease) (PDF). Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. 17 February 2020.

- ^ Joshua Hunt. "Japan Is Racing to Test Favipiravir, a Drug to Treat Covid-19". WIRED. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ "Japan might approve anti-flu drug Avigan to treat coronavirus patients". The Japan Times Online. The Japan Times. 22 February 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ "Abe Orders Basic Coronavirus Policy with Eye on Epidemic" Archived 31 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Nippon.com, 23 February 2020

- ^ "Japanese Experts Discuss Basic Coronavirus Policy". nippon.com. 24 February 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ 新型コロナウイルス感染症対策専門家会議 (Novel Coronavirus Expert Meeting) (24 February 2020). "新型コロナウイルス感染症対策の基本方針の具体化に向けた見解 (Opinion on the Realization of Basic Policies for Novel Coronavirus Disease Control)". Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare.

- ^ a b c d "Coronavirus Basic Policy Impacts Japan's Health, Education Systems". Nippon.com, 2 March 2020

- ^ "新型コロナウイルス感染症対策の基本方針 (Basic Policies for Novel Coronavirus Disease Control)" (PDF). Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet. 25 February 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ "Basic Policies for Novel Coronavirus Disease Control". Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet, 25 February 2020.

- ^ "Japan to create a fund to subsidize parents during school closure-Nikkei". Financial Post, 28 February 2020.

- ^ Coronavirus: National Health Insurance to Cover Virus Test Archived 31 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Nippon.com, 27 February 2020

- ^ The Government of Japan, Expert Meeting on the Novel Coronavirus Disease Control (9 March 2020). "Views on the Novel Coronavirus Disease Control (Summary Version)" (PDF). Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (in English). Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ 新型コロナウイルス感染症対策専門家会議 (9 March 2020). "新型コロナウイルス感染症対策の見解" (PDF) (in Japanese). Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ NEWS K. "Japan local gov'ts urged to prepare for peak of coronavirus infections". Kyodo News+. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ "Lawmakers slammed for using coronavirus to justify emergency clause for Japan's Constitution, curbing rights". The Japan Times, 5 February 2020.

- ^ NEWS K. "Japan's Diet gives Abe power to declare emergency amid viral fears". Kyodo News+. Kyodo News. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ Revised influenza law to allow Japan PM to declare state of emergency over coronavirus. The Mainichi, 5 March 2020

- ^ NEWS K. "Japan PM Abe to declare state of emergency amid surge in virus infections". Kyodo News+. Kyodo News. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ Tomohiro Osaki "How far can Japan go to curb the coronavirus outbreak? Not as far as you may think. The Japan Times, 1 March 2020.

- ^ "Tokyo governor urges people to stay indoors over the weekend as virus cases spike". Japan Times. Kyodo News, Reuters. 25 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ "Tokyo residents asked to stay indoors at weekend due to coronavirus". The Mainichi. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Sugiyama S (26 March 2020). "Japan coronavirus task force may set stage for state of emergency". The Japan Times Online. ISSN 0447-5763. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Koike calls for fewer outings; says state of emergency up to PM". Japan Today. 31 March 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ NEWS K. "Calls grow for Japan PM to declare state of emergency over virus". Kyodo News+. Kyodo News. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Japan's cities scramble to move mild coronavirus patients to hotels". Nikkei Asian Review. Nihon Keizai Shimbun. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Tokyo reports 83 new coronavirus infections". Kyodo News+. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ "Tokyo to ask shopping malls, leisure facilities, pubs to close". The Asahu Shimbun. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ "How to reduce physical contact with others by 80%: Japan medical experts". Mainichi Daily News. 毎日新聞. 10 April 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ "일본 코로나 감염 300여명 새로 확인…하루 최대폭 증가(종합)". mk.co.kr (in Korean). 연합뉴스. 매일경제. 3 April 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ Yamaguchi N (3 April 2020). "COVID-19 IN JAPAN: TRAVEL BAN NOW INCLUDES UNITED STATES, OTHER MAJOR TRADING PARTNERS". Morganlewis.com. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ Saito T, Muto K, Tanaka M, Okabe N, Oshitani H, Kamayachi S, Kawaoka Y, Kawana A, Suzuki M, Tateda K, Nakayama H, Yoshida M, Imamura A, Ohtake F, Ohmagari N (October 2021). "Proactive Engagement of the Expert Meeting in Managing the Early Phase of the COVID-19 Epidemic, Japan, February–June 2020". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 27 (10): 1–9. doi:10.3201/eid2710.204685. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 8462345. PMID 34546168.

- ^ "Tokyo issues closure requests for 6 categories | NHK WORLD-JAPAN News". NHK WORLD. NHK. Retrieved 17 April 2020.[dead link]

- ^ "「接触7割減」では収束まで長期化 北大教授が警鐘" ["Prolonged convergence in "70% reduction in contact" will be alarmed by Professor Hokkaido University"] (in Japanese). Nihon Keizai Shimbun. 11 April 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "新型コロナ感染拡大、接触6割減でも感染者数減らず" [The number of infected people does not decrease even if the new corona infection spreads and the contact 60% decrease]. TBS NEWS (in Japanese). Tokyo Broadcasting System. Retrieved 17 April 2020.[dead link]

- ^ "Japan's Prime Minister Expected to Extend COVID-19 State of Emergency". Voice of America. 4 May 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ "Japan to lift coronavirus emergency outside Tokyo, Osaka regions". Kyodo news. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "緊急事態宣言、大阪、兵庫、京都を解除 首都圏と北海道、25日にも" [Emergency Declaration, Osaka, Hyogo Canceled; Tokyo Metropolitan area and Hokkaido, remains until 25th]. Jiji Press Agency (in Japanese). 21 May 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ "首都圏、25日にも判断 緊急事態宣言、関西3府県解除" [Tokyo metropolitan area, also determined on the 25th: Emergency situation declared, Kansai 3 prefectures lifted]. Nihon Keizai Shimbun (in Japanese). 21 May 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ "新型コロナウイルス感染症対策専門家会議の開催について" (PDF). 首相官邸 (Prime Minister's Office of Japan) (in Japanese). 15 April 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Eighth Meeting of the Novel Coronavirus Response Headquarters. Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet, 12 February 2020.

- ^ "COVID-19: Brief overview of Risk Governance Approach from Japan (Part 3)" (PDF). NIDM. 6 April 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ "Abe seeks opposition help for emergency virus bill as cases top 1,000". Kyodo News+. KYODO NEWS. 5 March 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ "3つの"密"を避けて外出を…新型コロナで厚労省が新たな注意喚起を公表". FNNプライムオンライン (in Japanese). 23 March 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ 首相官邸(災害・危機管理情報) (17 March 2020). "【注意喚起】#新型コロナウイルス に関するお知らせ". Twitter @kantei_saigai (in Japanese). Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ "「3つの密」、誕生の背景とは? – 押谷・東北大教授(厚労省クラスター対策班)|医療維新 – m3.comの医療コラム". www.m3.com (in Japanese). Retrieved 15 May 2020.