1980 Turkish coup d'état

| 1980 Turkish coup d'état | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War | |||||||

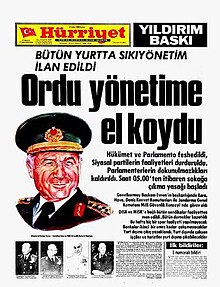

Daily newspaper Hürriyet's headline on 12 September 1980: "The army has seized the government." | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Opposition of Turkey | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Kenan Evren Nurettin Ersin Tahsin Şahinkaya Nejat Tümer Sedat Celasun |

Süleyman Demirel Bülent Ecevit | ||||||

The 1980 Turkish coup d'état (Turkish: 12 Eylül Darbesi, lit. 'September 12 coup d'état'), headed by Chief of the General Staff General Kenan Evren, was the third coup d'état in the history of the Republic of Turkey, the previous having been the 1960 coup and the 1971 coup by memorandum.

During the Cold War era, Turkey saw political violence (1976–1980) between the far-left, the far-right (Grey Wolves), the Islamist militant groups, and the state.[2][3][4] The violence saw a sharp downturn for a period after the coup, which was welcomed by some for restoring order[5] by quickly executing 50 people and arresting 500,000, of which hundreds would die in prison.[6]

For the next three years the Turkish Armed Forces ruled the country through the National Security Council, before democracy was restored with the 1983 Turkish general election.[7] This period saw an intensification of the Turkish nationalism of the state, including banning the Kurdish language.[8][9][10] Turkey partially returned to democracy in 1983 and fully in 1989.

Prelude

The 1970s in Turkey was characterized by political turmoil and violence.[11] Since 1968–69, a proportional representation system had made it difficult for any one party to achieve a parliamentary majority. The interests of the industrial bourgeoisie, which held the largest holdings of the country, were opposed by other social classes such as smaller industrialists, traders, rural notables, and landlords, whose interests did not always coincide among themselves. Numerous agricultural and industrial reforms sought by parts of the middle upper classes were blocked by others. By the end of the 1970s, Turkey was in an unstable situation with unsolved economic and social problems, facing strike actions, and the partial paralysis of parliamentary politics. The Grand National Assembly of Turkey had been unable to elect a president during the six months preceding the coup.[12]

In 1975 conservative Justice Party (Turkish: Adalet Partisi) leader Süleyman Demirel was succeeded as prime minister by the leader of the social-democratic Republican People's Party (Turkish: Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi), Bülent Ecevit.

Demirel formed a coalition with the Nationalist Front (Turkish: Milliyetçi Cephe), the National Salvation Party (Turkish: Millî Selamet Partisi, an Islamist party led by Necmettin Erbakan), and the far-right Nationalist Movement Party (Turkish: Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi, MHP) led by Alparslan Türkeş.

The MHP used the opportunity to infiltrate state security services, seriously aggravating the low-intensity war between the rival factions.[12] Politicians seemed unable to stem the growing violence in the country.

The elections of 1977 had no winner. At first, Demirel continued the coalition with the Nationalist Front. But in 1978, Ecevit once again took power with the help of some deputies who had moved from one party to another, until 1979, when Demirel once again became prime minister.

Unprecedented political violence erupted in Turkey in the late 1970s. The overall death toll of the 1970s is estimated at 5,000, with nearly ten assassinations per day.[12] Most were members of left-wing and right-wing political organizations, then engaged in bitter fighting. The ultra-nationalist Grey Wolves, the youth organisation of the MHP, claimed they were supporting the security forces.[7] According to the anti-fascist Searchlight magazine, in 1978 there were 3,319 fascist attacks, in which 831 were killed and 3,121 wounded.[13]

In the central trial against the radical left-wing organization Devrimci Yol (Revolutionary Path) at Ankara Military Court, the defendants listed 5,388 political killings before the military coup. Among the victims were 1,296 right-wingers and 2,109 left-wingers. Other killings couldn't be definitely connected, but were most likely politically inspired.[14] The 1977 Taksim Square massacre, the 1978 Bahçelievler massacre, and the 1978 Maraş massacre stood out. Following the Maraş massacre, martial law was announced in 14 of (then) 67 provinces in December 1978. By the time of the coup, it had been extended to 20 provinces.

Ecevit was warned about the coming coup in June 1979 by Nuri Gündeş of the National Intelligence Organization Turkish: Milli İstihbarat Teşkilatı, (MİT)). Ecevit told his interior minister, İrfan Özaydınlı, who then passed the news on to Sedat Celasun—one of the five generals who would lead the coup. (The deputy undersecretary of the MİT, Nihat Yıldız, was demoted to the London consulate and replaced by a lieutenant general as a result).[15]

Coup

On 11 September 1979, General Kenan Evren ordered a hand-written report from full general Haydar Saltık on whether a coup was in order or the government merely needed a stern warning. The report, which recommended preparing for a coup, was delivered in six months. Evren kept the report in his office safe.[16] Evren says the only other person beside Saltık who was aware of the details was Nurettin Ersin. It has been argued that this was a plot on Evren's part to encompass the political spectrum, as Saltık was close to the left, while Ersin took care of the right. Backlash from political organizations after the coup would therefore be prevented.[17]

On 21 December, the War Academy generals convened to decide the course of action. The pretext for the coup was to put an end to the social conflicts of the 1970s, as well as the parliamentary instability. They resolved to issue the party leaders (Süleyman Demirel and Bülent Ecevit) a memorandum by way of the president, Fahri Korutürk, which was done on 27 December. The leaders received the letter a week later.[16]

A second report, submitted in March 1980, recommended undertaking the coup without further delay, otherwise apprehensive lower-ranked officers might be tempted to "take the matter into their own hands".[16] Evren made only minor amendments to Saltık's plan, titled "Operation Flag" (Turkish: Bayrak Harekâtı).[17]

The coup was planned to take place on 11 July 1980, but was postponed after a motion to put Demirel's government to a vote of confidence was rejected on 2 July. At the Supreme Military Council meeting (Turkish: Yüksek Askeri Şura) on 26 August, a second date was proposed: 12 September.[16]

On 7 September 1980, Evren and the four service commanders decided that they would overthrow the civilian government. On 12 September, the National Security Council (Turkish: Milli Güvenlik Konseyi, MGK), headed by Evren declared coup d'état on the national channel. The MGK then extended martial law throughout the country, abolished the Parliament and the government, suspended the Constitution and banned all political parties and trade unions. They invoked the Kemalist tradition of state secularism and in the unity of the nation, which had already justified the precedent coups, and presented themselves as opposed to communism, fascism, separatism and religious sectarianism.[12]

The nation learned of the coup at 4:30 AM UTC+3 on the state radio address announcing that the parliament had been dismissed and that the country was under the control of the Turkish Armed Forces. According to the Armed Forces broadcast, the coup was needed to save the Turkish Republic from political fragmentation, violence and the economic collapse that was created by political mismanagement. Kenan Evren was appointed head of the National Security Council (Turkish: Milli Güvenlik Konseyi).[11]

Effects

In the days following the coup the NSC suspended parliament, disbanded all political parties and took their leaders in custody. Workers' strikes were made illegal and labor unions were suspended. Local governors, mayors and public servants were replaced by military personnel. Curfews were imposed in the evenings under the declared state of emergency and leaving the country was prohibited. By the end of 1982 over 120,000 people had been imprisoned.[11]

Istanbul was served by three military mayors between 1980 and 1984. They renamed the leftist shantytowns changing names like "1 Mayıs Mahallesi" (Eng.: "1st of May Neighborhood") to "Mustafa Kemal Mahallesi" (Eng.: "Mustafa Kemal Neighborhood"), as a symbol of the military rule.[11]

Economy

One of the coup's most visible effects was on the economy. On the day of the coup, it was on the verge of collapse, with triple-digit inflation. There was large-scale unemployment and a chronic foreign trade deficit. The economic changes between 1980 and 1983 were credited to Turgut Özal. In 1979, Özal became an undersecretary in Demirel's minority government until the coup. As an undersecretary, he played a major role in developing economic reforms, known as the 24 January decisions, which paved the way for greater neoliberalism in the Turkish economy. After the coup, he was appointed Deputy Prime Minister of Turkey responsible for the economy in Ulusu's government and continued to implement economic reforms. Özal supported the International Monetary Fund, and to this end he forced the resignation of the director of the Central Bank, İsmail Aydınoğlu, who opposed it.

The strategic aim was to unite Turkey with the "global economy," which big business supported,[18] and gave Turkish companies the ability to market products and services globally. One month after the coup, London's International Banking Review wrote "A feeling of hope is evident among international bankers that Turkey's military coup may have opened the way to greater political stability as an essential prerequisite for the revitalization of the Turkish economy".[19] During 1980–1983, the foreign exchange rate was allowed to float freely. Foreign investment was encouraged. The national establishments, initiated by Atatürk's Reforms, were promoted to involve joint enterprises with foreign establishments. The 85% pre-coup level government involvement in the economy forced a reduction in the relative importance of the state sector. Just after the coup, Turkey revitalized the Atatürk Dam and the Southeastern Anatolia Project, which was a land reform project promoted as a solution to the underdeveloped Southeastern Anatolia. It was transformed into a multi-sector social and economic development program, a sustainable development program, for the 9 million people of the region. The closed economy, produced for only Turkey's need, was subsidized for a vigorous export drive.

The drastic expansion of the economy during this period was relative to the previous level. The GDP remained well below those of most Middle Eastern and European countries. The government froze wages while the economy experienced a significant decrease of the public sector, a deflationist policy, and several successive mini-devaluations.[12]

Tribunals

The coup rounded up members of both the left and right for trial with military tribunals. Within a very short time, there were 250,000[7] to 650,000 people detained. Among the detainees, 230,000 were tried, 14,000 were stripped of citizenship, and 50 were executed.[20] In addition, hundreds of thousands of people were tortured, and thousands disappeared. A total of 1,683,000 people were blacklisted.[21] Apart from the militants killed during shootings, at least four prisoners were legally executed immediately after the coup; the first ones since 1972, while in February 1982 there were 108 prisoners condemned to capital punishment.[12] Among the prosecuted were Ecevit, Demirel, Türkeş, and Erbakan, who were incarcerated and temporarily suspended from politics.

One notable victim of the hangings was a communist militant alleged 17-year-old Erdal Eren, who said he looked forward to it in order to avoid thinking of the torture he had witnessed.[22] According to official records he was born in 1961. He was accused of killing a Turkish soldier. Kenan Evren said "Now, after I catch him, I will put him on trial, and then I will not execute him, I will take care of him for life. I will feed that traitor who took a gun to these Mehmetçiks who shed their blood for this homeland for years. Would you agree to that?!"[23]

After having taken advantage of the Grey Wolves' activism, General Kenan Evren imprisoned hundreds of them. At the time they were some 1700 Grey Wolves organizations in Turkey, with about 200,000 registered members and a million sympathizers.[24] In its indictment of the MHP in May 1981, the Turkish military government charged 220 members of the MHP and its affiliates for 694 murders.[13] Evren and his cohorts realized that Türkeş was a charismatic leader who could challenge their authority using the paramilitary Grey Wolves.[25] Following the coup in Colonel Türkeş's indictment, the Turkish press revealed the close links maintained by the MHP with security forces as well as organized crime involved in drug trade, which financed in return weapons and the activities of hired fascist commandos all over the country.[12]

Constitution

Within three years the generals passed some 800 laws in order to form a militarily disciplined society.[26] The coup members were convinced of the unworkability of the existing constitution. They decided to adopt a new constitution that included mechanisms to prevent what they saw as impeding the functioning of democracy. On 29 June 1981 the military junta appointed 160 people as members of an advisory assembly to draft a new constitution. The new constitution brought clear limits and definitions, such as on the rules of election of the president, which was stated as a factor for the coup d'état.

On 7 November 1982 the new constitution was put to a referendum, which was accepted with 92% of the vote. On 9 November 1982 Kenan Evren was appointed President for the next seven years.

Education

The junta made mandatory the lesson named "Religious Culture and Moral Knowledge", which in practice centers around Sunni Islam.[citation needed]

Result

- 650,000 people were under arrest.

- 1,683,000 people were blacklisted.

- 230,000 people were tried in 210,000 lawsuits.

- 7,000 people were recommended for the death penalty.

- 517 people were sentenced to death.

- 50 of those given the death penalty were executed (26 political prisoners, 23 criminal offenders and 1 ASALA militant).

- The files of 259 people, which had been recommended for the death penalty, were sent to the National Assembly.

- 71,000 people were tried by articles 141, 142 and 163 of Turkish Penal Code.

- 98,404 people were tried on charges of being members of a leftist, a rightist, a nationalist, a conservative, etc. organization.

- 388,000 people were denied a passport.

- 30,000 people were dismissed from their firms because they were suspects.

- 14,000 people had their citizenship revoked.

- 30,000 people went abroad as political refugees.

- 300 people died in a suspicious manner.

- 171 people died by reason of torture.

- 937 films were banned because they were found objectionable.

- 23,677 associations had their activities stopped.

- 3,854 teachers, 120 lecturers and 47 judges were dismissed.

- 400 journalists were sentenced to 3,315 years and 6 months imprisonment, and 31 journalists were actually imprisoned.

- 300 journalists were attacked.

- 3 journalists were shot dead.

- 300 days in which newspapers were not published.

- 303 cases were opened for 13 major newspapers.

- 39 tonnes of newspapers and magazines were destroyed.

- 299 people lost their lives in prison.

- 144 people died in a suspicious manner in prison.

- 14 people died in hunger strikes in prison.

- 16 people were shot while fleeing.

- 95 people were killed in combat.

- "Natural death report" for 73 persons was given.

- The cause of death of 43 people was announced as "suicide".

Source: The Grand National Assembly of Turkey (Turkish: Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi – TBMM)[27]

Aftermath

After the approval by referendum of the new Constitution in June 1982, Kenan Evren organized general elections, held on 6 November 1983. This democratization has been criticized by the Turkish scholar Ergun Özbudun as a "textbook case" of a junta's dictating the terms of its departure.[28]

The referendum and the elections did not take place in a free and competitive setting. Many political leaders of pre-coup era (including Süleyman Demirel, Bülent Ecevit, Alparslan Türkeş and Necmettin Erbakan) had been banned from politics, and all new parties needed to get the approval of the National Security Council in order to participate in the elections. Only three parties, two of which were actually created by the junta, were permitted to contest.

The secretary general of the National Security Council was general Haydar Saltık. Both he and Evren were the strong men of the regime, while the government was headed by a retired admiral, Bülend Ulusu, and included several retired military officers and a few civil servants. Some alleged in Turkey, after the coup, that General Saltuk had been preparing a more radical, rightist coup, which had been one of the reasons prompting the other generals to act, respecting the hierarchy, and then to include him in the MGK in order to neutralize him.[12]

Out of the 1983 elections came one-party governance under Turgut Özal's Motherland Party, which combined a neoliberal economic program with conservative social values.

Yıldırım Akbulut became the head of the Parliament. He was succeeded in 1991 by Mesut Yılmaz. Meanwhile, Süleyman Demirel founded the center-right True Path Party in 1983, and returned to active politics after the 1987 Turkish referendum.

Yılmaz redoubled Turkey's economic profile, converting towns like Gaziantep from small provincial capitals into mid-sized economic boomtowns, and renewed its orientation toward Europe. But political instability followed as the host of banned politicians reentered politics, fracturing the vote, and the Motherland Party became increasingly corrupt. Özal, who succeeded Evren as President of Turkey, died of a heart attack in 1993, and Süleyman Demirel was elected president.

The Özal government empowered the police force with intelligence capabilities to counter the National Intelligence Organization, which at the time was run by the military. The police force even engaged in external intelligence collection.[29]

Trial of coup leaders

After the 2010 constitutional referendum, an investigation was started regarding the coup, and in June 2011, the Specially Authorized Ankara Deputy Prosecutor's Office asked ex-prosecutor Sacit Kayasu to forward a copy of an indictment he had prepared for Kenan Evren. Kayasu had previously been fired for trying to indict Evren in 2003.[30]

In January 2012, a Turkish court accepted the indictments against General Kenan Evren and General Tahsin Şahinkaya, the only coup leaders still alive at the time, for their role in the coup. Prosecutors sought life sentences against the two retired generals.[31] According to the indictment, a total of 191 people died in custody during the aftermath of the coup, due to "inhumane" acts.[32] The trial began on 4 April 2012.[33] In 2012, a court case was launched against Şahinkaya and Kenan Evren relating to the 1980 military coup. Both were sentenced to life imprisonment on 18 June 2014 by a court in Ankara. But neither of the two was sent to prison as both were in hospitals for medical treatment.[34] Şahinkaya died in the Gülhane Military Medical Academy Hospital (GATA) in Haydarpaşa, Istanbul on 9 July 2015.[34] Evren died at a military hospital in Ankara on 9 May 2015, aged 97. His sentence was on appeal at the time of his death.

Allegations of the U.S. involvement

There have been allegations of American involvement in the coup. Involvement was alleged to have been acknowledged by the CIA Ankara station chief Paul B. Henze. In his 1986 book 12 Eylül: saat 04.00 journalist Mehmet Ali Birand wrote that after the government was overthrown, Henze cabled Washington, saying, "our boys did it."[35] On a June 2003 interview to Zaman, Henze denied American involvement stating "I did not say to Carter 'Our boys did it.' It is totally a tale, a myth, it is something Birand fabricated. He knows it, too. I talked to him about it".[36] Two days later Birand replied on CNN Türk's Manşet by saying "It is impossible for me to have fabricated it, the American support to the coup and the atmosphere in Washington was in the same direction. Henze narrated me these words despite he now denies it"[37] and presented the footage of an interview with Henze recorded in 1997 according to which another diplomat rather than Henze informed the president, saying "Boys in Ankara did it."[38] However, according to the same interview, Henze, the CIA and the Pentagon did not know about the coup beforehand.[38] Some Turkish media sources reported it as "Henze indeed said Our boys did it",[39] while others simply called the statement an urban legend.[40]

The US State Department itself announced the coup during the night between 11 and 12 September: the military had phoned the US embassy in Ankara to alert them of the coup an hour in advance.[41] Both in his press conference held after the government was overthrown[42] and when interrogated by public prosecutor in 2011[43] General Kenan Evren said "the US did not have pre-knowledge of the coup but we informed them of the coup 2 hours in advance due to our soldiers coinciding with the American community JUSMAT that is in Ankara."

Tahsin Şahinkaya – then general in charge of the Turkish Air Forces who is said to have travelled to the United States just before the coup, told the US army general was not informed of the upcoming coup and the general was surprised to have been uninformed of the coup after the government was overthrown.[44] Michael Butter argued that outside of some anecdotes, there was no proof of American involvement.[45]

In culture

The coup has been criticised in many Turkish movies, TV series and songs since 1980.

Movies

- 1986 – Sen Türkülerini Söyle (Şerif Gören)

- 1986 – Dikenli Yol (Zeki Alasya)

- 1986 – Prenses (Sinan Çetin)

- 1986 – Ses (Zeki Ökten)

- 1987 – Hunting Time (Av Zamanı) (Erden Kıral)

- 1987 – Kara Sevdalı Bulut (Muammer Özer)

- 1988 – Sis (Zülfü Livaneli)

- 1988 – Kimlik (Melih Gülgen)

- 1989 – Bütün Kapılar Kapalıydı (Memduh Ün)

- 1989 – Uçurtmayı Vurmasınlar (Tunç Başaran)

- 1990 – Bekle Dedim Gölgeye (Atıf Yılmaz)

- 1991 – Uzlaşma (Oğuzhan Tercan)

- 1994 – Babam Askerde (Handan İpekçi)

- 1995 – 80. Adım (Tomris Giritlioğlu)

- 1998 – Gülün Bittiği Yer (İsmail Güneş)

- 1999 – Eylül Fırtınası (Atıf Yılmaz)

- 2000 – Coup/Darbe - A Documentary History of the Turkish Military Interventions (Documentary, Elif Savaş Felsen)

- 2005 – Babam ve Oğlum (Çağan Irmak)

- 2006 – Beynelmilel (Sırrı Süreyya Önder)

- 2006 – Home Coming (Eve Dönüş) (Ömer Uğur)

- 2007 – Zincirbozan (Atıl İnaç)

- 2008 – O... Çocukları (Murat Saraçoğlu)

- 2010 – September 12 (Özlem Sulak)

- 2015 – Bizim Hikaye

- 2015 – Kar Korsanları

- 2015 – Kafes

- 2019 – Miracle in Cell No. 7

Television series

- 2004 – Çemberimde Gül Oya

- 2007 – Hatırla Sevgili

- 2009 – Bu Kalp Seni Unutur Mu?

- 2012 – Seksenler

- 2010 – Öyle Bir Geçer Zaman Ki

Music

- Cem Karaca (1992), maNga (2006), Ayben (2008), 'Raptiye Rap Rap' (1992)

- Fikret Kızılok 'Demirbaş' (1995)

- Grup Yorum: Büyü – (Composed in memory of Erdal Eren)

- Hasan Mutlucan, 'Yine de Şahlanıyor'

- Mor ve Ötesi, 'Darbe' (2006)

- Ozan Arif, Yaşıyor Kenan Paşa

- Ozan Arif, 'Seksenciler'

- Ozan Arif, 'Muhasebe'(12 Eylül)

- Ozan Arif, Bir İt Vardı

- Sexen, A.D. 12 September Listen

- Sexen, Censored Inc. Listen

- Sezen Aksu, 'Son Bakış' (1989)

- Suavi 'Eylül' (1996)

- Teoman and Yavuz Bingöl, 'İki Çocuk' (2006)

- Özdemir Erdoğan, 'Gurbet Türküsü'

- Ezginin Günlüğü, '1980'

- Kramp, 'Lan N'oldu?'

See also

- 1960 Turkish coup d'état

- 1971 Turkish military memorandum

- 1997 Turkish military memorandum

- 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt

- Diyarbakır Prison

- History of Turkey

- List of modern conflicts in the Middle East

References

- ^ Gunter, Michael M. (January 1989). "Political Instability in Turkey During the 1970s". Journal of Conflict Studies. 9 (1).

- ^ Zürcher, Erik J. (2004). Turkey A Modern History, Revised Edition. I.B.Tauris. p. 263. ISBN 978-1-85043-399-6.

- ^ Ganser 2005, p. 235: Colonel Talat Turhan accused the United States for having fuelled the brutality from which Turkey suffered in the 1970s by setting up the Special Warfare Department, the Counter-Guerrilla secret army and the MIT and training them according to FM 30–31

- ^ Naylor, Robert T (2004). Hot Money and the Politics of Debt (3E ed.). McGill-Queen's Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-7735-2743-0. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

The fact that militias of all political tendencies seemed to be buying their arsenals from the same sources pointed to the possibility of a deliberate orchestration of the violence – of the sort P2 had attempted in Italy a few years earlier – to prepare the psychological climate for a military coup.

- ^ Ustel, Aziz (14 July 2008). "Savcı, Ergenekon'u Kenan Evren'e sormalı asıl!". Star Gazetesi (in Turkish). Retrieved 21 October 2008.

Ve 13 Eylül 1980'de Türkiye'yi on yıla yakın bir süredir kasıp kavuran terör ve adam öldürmeler bıçakla kesilir gibi kesildi.

- ^ "Turkey and its army: Erdogan and his generals". The Economist. 2 February 2013.

- ^ a b c Amnesty International, Turkey: Human Rights Denied, London, November 1988, AI Index: EUR/44/65/88, ISBN 978-0-86210-156-5, pg. 1.

- ^ "Turkey's Kurdish Conflict and Retreat from Democracy".

- ^ "PKK's decades of violent struggle - CNN.com".

- ^ "Turkey's DTP says 1980 coup waged "cultural genocide" on Kurds". 21 October 2008.

- ^ a b c d Gul, Murat. "Architecture and the Turkish City," p. 153

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gil, Ata. "La Turquie à marche forcée," Le Monde diplomatique, February 1981.

- ^ a b Searchlight, No.47 (May 1979), pg. 6. Quoted by (Herman & Brodhead 1986, p. 50)

- ^ Devrimci Yol Savunması (Defense of the Revolutionary Path). Ankara, January 1989, p. 118-119.

- ^ Ünlü, Ferhat (17 July 2007). "Çalınan silahlar falcıya soruldu". Sabah (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 30 August 2008.

- ^ a b c d Doğan, İbrahim (1 September 2008). "Evren, darbe için iki rapor hazırlatmış". Aksiyon (in Turkish). 717. Feza Gazetecilik A.Ş. Archived from the original on 12 September 2008.

Haydar Paşa, size vereceğim bu görevden sadece kuvvet komutanlarının haberi var. İç güvenliğimizin tehlikede olduğunu pek çok defa konuştuk. Silahlı Kuvvetlerin içine de sızmalar başladığını biliyorsunuz. Sizden bir çalışma grubu kurmanızı istiyorum. İki kurmayı görevlendirin. Araştırmanızı istediğim, yönetime müdahale için zamanı geldi mi? Ya da uyarıda mı bulunmak daha uygun olur? Bu hususlar etüt edilecek. Arada rapor verin. Hiçbir şey kayda geçmeyecek. Tek nüsha yazılsın. Elle… Bugün 11 Eylül, altı ay içinde tamamlayın. Bir de görevlendireceğimiz kişilere maske görev verin. Etrafın dikkatini çekmesin.

- ^ a b Oğur, Yıldıray (17 September 2008). "12 Eylül'ün darbeci solcusu: Ali Haydar Saltık". Taraf (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 27 September 2008.

- ^ Ekinci, Burhan (12 September 2008). "12 Eylül sermayenin darbesiydi". Taraf. Archived from the original on 13 September 2008.

- ^ Naylor, R. Thomas (2004). "6. Of Dope, Debt, and Dictatorship". Hot Money and the Politics of Debt. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-7735-2743-0.

- ^ "Turkey still awaits to confront with generals of the coup in 12 Sep 1980". Hurriyet English. 9 October 2008. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008.

- ^ "12 Eylül'de 1 milyon 683 bin kişi fişlendi". Hürriyet (in Turkish). ANKA. 12 September 2008.

- ^ Türker, Yıldırım (12 September 2005). "Çocuğu astılar". Radikal (in Turkish). sec. Yaşam. Archived from the original on 24 October 2005.

Cezaevinde yapılan (neler olduğunu ayrıntılı bir biçimde öğrenirsiniz sanırım) insanlık dışı zulüm altında inletildik. O kadar aşağılık, o kadar canice şeyler gördüm ki, bugünlerde yaşamak bir işkence haline geldi. İşte bu durumda ölüm korkulacak bir şey değil, şiddetle arzulanan bir olay, bir kurtuluş haline geldi. Böyle bir durumda insanın intihar ederek yaşamına son vermesi işten bile değildir. Ancak ben bu durumda irademi kullanarak ne pahasına olursa olsun yaşamımı sürdürdüm. Hem de ileride bir gün öldürüleceğimi bile bile.

- ^ Oran, Baskın; Evren, Kenan (1989). Kenan Evren'in yazılmamış anıları (in Turkish). Bilgi Yayınevi. p. 189. ISBN 975-494-095-9. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

Şimdi ben, bunu yakaladıktan sonra mahkemeye vereceğim ve ondan sonra da idam etmeyeceğim, ömür boyu ona bakacağım. Bu vatan için kanını akıtan bu Mehmetçiklere silah çeken o haini ben senelerce besleyeceğim. Buna siz razı olur musunuz?

(3 October 1984 speech at Muş) - ^ (Herman & Brodhead 1986, p. 50)

- ^ Ergil, Dogu (2 May 1997). "Nationalism With and Without Turkes". Turkish Daily News. Hürriyet. Archived from the original on 18 April 2013.

The leaders of the 1980 military coup d'état knew that the paramilitary force of the NAP would dilute their authority because the party was an alternative organization directly attached to the personality of Turkes.

- ^ History of the Kurdish Uprising[usurped] a paper of the International Council on Human Rights Policy[usurped]. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- ^ The report was prepared between 2 May 2012 and 28 November 2012 by the Parliamentary Investigation Commission for the Coups and the Memorandums: “(Ordinal) 376, Volume 1, Page 15, Paragraph 4 (continues on page 16, the first 5 lines) Archived 23 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine” [The report was released in Turkish. And 'The Results' section was translated to English by a Wikipedia user.]

- ^ Özbudun, Ergun. Contemporary Turkish Politics: Challenges to Democratic Consolidation, Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2000, pg. 117. "The 1983 Turkish transition is almost a textbook example of the degree to which a departing military regime can dictate the conditions of its departure (...)."

- ^ Sariibrahimoglu, Lale (7 December 2008). "Turkey needs an intelligence coordination mechanism, says Güven". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008.

Shortly after the 1980 military coup, the government, under the late Prime Minister Turgut Özal, introduced a law that strengthened the power of the police forces to counter the MİT, which was headed by a general at the time.

- ^ "Ankara prosecutors to examine Kayasu's indictment against coup leader Evren". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- ^ BBC News Turkish ex-president Kenan Evren faces coup charge, 10 January 2012

- ^ Today's Zaman Fears of suicide prompt Evren family to remove coup leader's firearms Archived 20 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 19 January 2012

- ^ Why does Evren still think so? Archived 23 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 22 March 2012

- ^ a b "Last living commander of the 1980 coup, Tahsin Şahinkaya dies at 90". Daily Sabah. 9 July 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ Birand, Mehmet Ali. 12 eylül: saat 04.00. p. 1.

- ^ “Başkan Carter’a 'Bizim çocuklar bu işi başardı' demedim. Bu tümüyle bir efsane, bir mit. Gazeteci Mehmet Ali Birand’ın uydurmuş olduğu bir şey. O da biliyor bunu. Bu konuda kendisiyle de konuştum zaten.” – Paul Henze: ‘Bizim çocuklar işi başardı’ sözünü Birand uydurdu – by Ibrahim Balta. Zaman 12 June 2003

- ^ "Mehmet Ali Birand, bu sözlere ‘'Bu şekilde uydurmama imkan yok. 12 Eylül'e ABD'nin verdiği destek ve Washington'daki hava da aynı yöndeydi. Sonradan reddetmesine rağmen Henze bana bu sözleri söyledi'’ diye karşılık verdi." – Paul Henze ‘Bizim çocuklar yaptı’ demiş – Hürriyet, 14 June 2003.

- ^ a b "Kasete göre, Başkan Carter’a Ankara’daki darbeyi haber veren Henze değil, başka bir diplomat. Ancak olayı Birand’a anlatan Henze, "Ankara’daki çocuklar başardı". şeklindeki mesajın Carter’a iletildiğini anlatıyor." – "Birand’dan Paul Henze’ye ‘sesli–görüntülü’ yalanlama" Zaman gazetesi 14.06.2003 İbrahim Balta

- ^ Paul Henze ‘Bizim çocuklar yaptı’ demiş – Hürriyet 14 June 2013

- ^ "Remembering an Atatürkist coup". Hürriyet Daily News. 11 September 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Gil, Ata. "La Turquie à marche forcée". Le Monde Diplomatique. February 1981.

- ^ Evren, Kenan (1990). Kenan Evrenin anıları 2 (Memoirs of Kenan Evren 2). Milliyet yayınları. p. 46.

- ^ "'ABD'ye söyleyin, yönetime el koyuyoruz'". Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ ""Bizim çocuklar" haber vermiş". Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ Butter, Michael (6 October 2020). The Nature of Conspiracy Theories. John Wiley & Sons. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-5095-4083-9.

Bibliography

- Ganser, Daniele (2005). NATO's secret armies: Operation Gladio and terrorism in Western Europe. Contemporary security studies. London ; New York: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-5607-6.

- Herman, Edward S.; Brodhead, Frank (1986). The rise and fall of the Bulgarian connection. New York: Sheridan Square Publications. ISBN 978-0-940380-07-3.