1862 Atlantic hurricane season

| 1862 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

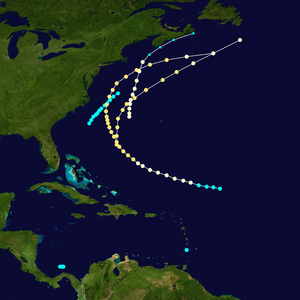

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | June 15, 1862 |

| Last system dissipated | November 25, 1862 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Two and Three |

| • Maximum winds | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total storms | 6 |

| Hurricanes | 3 |

| Total fatalities | 3 |

| Total damage | Unknown |

The 1862 Atlantic hurricane season featured six tropical cyclones, with only one making landfall. The season had three tropical storms and three hurricanes, none of which became major hurricanes.[nb 1] However, in the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 has been estimated.[2] Jose Fernandez-Partagas and Henry Diaz initially documented five tropical cyclones in a 1995 report on this season. A sixth system was added by Michael Chenoweth in 2003 from records taken in Colón, Panama.

The first tropical cyclone was observed as a tropical storm offshore the East Coast of the United States from June 15 to June 17. The second and third systems were active in mid-August and mid-September, respectively, and both attained Category 2 intensity at their peaks on the modern-day Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale and neither made landfall. A fourth tropical cyclone caused flooding in Saint Lucia and brought heavy rain to parts of Barbados on October 5, but its track prior to that date is unknown. The fifth hurricane was known to be active for a few days in October off the East Coast of the United States. Finally, a sixth system was centered near Panama – between November 22 and November 25.

Timeline

Systems

Tropical Storm One

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 15 – June 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); |

Based on reports from four ships, a tropical storm is known to have existed for two days in mid-June off the East Coast of the United States.[3] It formed approximately 340 miles (550 km) east of Savannah, Georgia on June 15 and moved slowly north before dissipating two days later, while located about 250 miles (400 km) east of Virginia Beach, Virginia.[4] Climate researcher Michael Chenoweth proposed the removal of this system from HURDAT, arguing that wind and pressure records obtained from the East Coast of the United States are more supportive of "elongated area of low pressure and strong high pressure building in, which is more consistent with a baroclinic system".[5]

Hurricane Two

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 18 – August 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); |

A Category 2 hurricane on the modern-day Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale was first seen on August 18, while located approximately 620 miles (1,000 km) east of Florida. Over the next three days, it tracked north and moved parallel to the East Coast of the United States. The system dissipated roughly 310 miles (500 km) south of Newfoundland on August 21.[4]

Hurricane Three

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 12 – September 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); |

On September 12, a Spanish ship, the Julian de Unsueta, was de-masted by a strong gale and thrown onto its beam ends. A few days later, she docked at Saint Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands. On September 13, the barques Montezuma and Gazelle were also both de-masted by a hurricane near Barbados. No information is available on the hurricane between September 14 to September 16, but on September 17, the barques Abbyla and Elias Pike encountered the hurricane, roughly 500 miles (800 km) off the coast of North Carolina. Several ships reported encountering hurricane conditions on September 19 off the East Coast of the United States, some as far north as Sable Island.[3] Based on these reports, the track began about 500 miles (800 km) northeast of the Virgin Islands on September 12 and ended on September 20 off the coast of Nova Scotia.[4]

Tropical Storm Four

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 6 – October 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); |

On October 5, a tropical storm caused flooding in Saint Lucia. That day and throughout the next, high winds and heavy rain were observed in Speightstown, Barbados. The storm may also have affected Saint Vincent. No track has been identified for the storm and it has been assigned a single location in the HURDAT database.[3]

Hurricane Five

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 14 – October 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); |

A modern-day Category 1 hurricane was first seen on October 14 approximately 310 miles (500 km) west of Bermuda.[4] A schooner, Albert Treat, encountered the storm and was thrown onto its beam ends. The schooner suffered considerable damage and three men drowned.[6] The next day, further north, the barque Acacia fell onto its beam ends, but managed to reach safety. Throughout October 16 the hurricane traveled northward, parallel to the East Coast of the United States. The ship Oder reported losing its sails in a hurricane off Sable Island that day. The Confederate cruiser Alabama lost its main yard and several sails, torn to shreds in the wind, and had two boats smashed.[7] The storm became extratropical around midday on October 16 and dissipated completely by October 17.[3]

Tropical Storm Six

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | November 22 – November 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); |

Based on meteorological records kept by an officer of the U.S. steamer James Adger, a strong tropical storm was centered to the northwest of Aspinwall, Panama from November 22 through to November 25. The storm weakened late on November 24 and began drifting slowly westward on November 25 before dissipating later that day.[8]

See also

Notes

- ^ A major hurricane is a storm that ranks as Category 3 or higher on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale.[1]

References

- ^ Christopher W. Landsea and Neal Dorst (June 2, 2011). "A: Basic Definitions". Hurricane Research Division: Frequently Asked Questions. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. A3) What is a super-typhoon? What is a major hurricane ? What is an intense hurricane ?. Retrieved December 27, 2011.

- ^ Christopher W. Landsea (2004). "The Atlantic hurricane database re-analysis project: Documentation for the 1851–1910 alterations and additions to the HURDAT database". In R. J. Murname and K.-B. Liu (ed.). Hurricanes and Typhoons: Past, Present and Future. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 177–221. ISBN 0-231-12388-4.

- ^ a b c d Jose Fernández-Partagás and Henry F. Diaz (1995a). A Reconstruction of Historical Tropical Cyclone Frequency in the Atlantic from Documentary and other Historical Sources 1851-1880 Part 1: 1851-1870. Boulder, Colorado: Climate Diagnostics Center, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved December 19, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Landsea, Chris (April 2022). "The revised Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT2) - Chris Landsea – April 2022" (PDF). Hurricane Research Division – NOAA/AOML. Miami: Hurricane Research Division – via Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory.

- ^ Chenoweth, Michael (December 2014). "A New Compilation of North Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1851–98". Journal of Climate. 27 (12). American Meteorological Society: 8674–8685. Bibcode:2014JCli...27.8674C. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-13-00771.1.

- ^ "MARINE INTELLIGENCE.; Cleared. Arrived. (Published 1862)". The New York Times. 1862-10-31. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- ^ Marvel, William (1996). The Sailor's Civil War: The Alabama and the Kearsarge. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 76–77. ISBN 0-8078-2294-9.

- ^ Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2008. Retrieved March 17, 2014.