14th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment

| 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment | |

|---|---|

State flag of Pennsylvania, c. 1863 | |

| Active | November 23, 1862, to August 24, 1865 |

| Country | United States |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | Union Army |

| Type | Cavalry |

| Size | Regiment |

| Engagements | American Civil War 1863: Battle of White Sulphur Springs, Battle of Droop Mountain 1864: Battle of Cove Mountain, Battle of Lynchburg, Second Battle of Kernstown, Battle of Moorefield, Third Battle of Winchester, Battle of Fisher's Hill, Battle of Cedar Creek |

| Commanders | |

| Colonel | James M. Schoonmaker |

| Lt. Col | William Blakeley |

| Major | Thomas Gibson |

| Major | John M. Daily |

The 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment (also known as the 159th Pennsylvania Volunteers) was a cavalry regiment of the Union Army during the American Civil War. Most of its fighting happened in the last half of 1863 and full year 1864. The regiment fought mainly in West Virginia and Virginia, often as part of a brigade or division commanded by Brigadier General William W. Averell and later Brigadier General William Powell.

The regiment was organized near Pittsburgh between August and November 1862. With the exception of one company from the Philadelphia area, its recruits were from western Pennsylvania. The regiment's original commander, Colonel James M. Schoonmaker, was one of the youngest regimental commanders in the Union Army at 20 years old. Pittsburgh attorney William Blakeley was the regiment's original lieutenant colonel.

Among battles where the regiment saw significant action were the Battle of White Sulphur Springs, Battle of Droop Mountain, Battle of Moorefield, and the Third Battle of Winchester. It had two officers and 97 enlisted men killed or mortally wounded. Disease killed 296 enlisted men. The three original Majors were Thomas Gibson, Shadrack Foley, and John M. Daily. Captain Thomas R. Kerr won the Medal of Honor for capturing a regimental flag at Moorefield where he was an advance scout, while Schoonmaker received the same award for action at the Third Battle of Winchester.

Formation and organization

James M. Schoonmaker, of Pittsburgh, began recruiting for a federal volunteer battalion of cavalry on August 18, 1862. At the time, he was a lieutenant in the Union's 1st Maryland Cavalry Regiment.[1] An accomplished horseman, he had so much success in recruiting that both Pennsylvania governor Andrew Gregg Curtin and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton authorized him to recruit a full cavalry regiment of 12 companies. With the exception of Philadelphia's Company A, recruiting was conducted in western Pennsylvania. Allegheny, Armstrong, and Fayette counties accounted for portions of eight of the regiment's 12 companies.[2] The men were mustered into service from August 21 through November 4, 1862, for three years.[3] By November, a full regiment was recruited, and it was mustered into service on November 23, 1862, as the 14th Pennsylvania Volunteer Cavalry.[4] In Pennsylvania, the regiment was also known as the One Hundred and Fifty-Ninth Pennsylvania Volunteers, since it was the 159th regiment of any branch raised in Pennsylvania.[5][Note 1]

Original leadership was Schoonmaker as colonel and William H. Blakeley as lieutenant colonel.[Note 2] Thomas Gibson, Shadrack Foley, and John M. Daily were majors of the First, Second, and Third battalions, respectively.[4] Other notable officers included Captain Ashbel F. Duncan of Company E and 2nd Lieutenant Thomas R. Kerr of Company C. Schoonmaker was only 20 years and four months old at the time, making him one of the youngest regiment commanders in the Union Army.[10] The regiment spent time at Camp Howe and Camp Montgomery, near Pittsburgh, before moving to Hagerstown, Maryland on November 24, where it received horses, arms, and equipment. On December 28, the regiment moved to Harper's Ferry, Virginia, where it was assigned picket and reconnaissance (scouting) duty.[3]

On May 7, 1863, a detachment of unmounted men was left in Harper's Ferry under the command of Major Foley, while the remaining portion of the regiment rode the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (a.k.a. B&O Railroad) west to join the 4th Separate Brigade of the VIII Army Corps at Grafton, Virginia (now West Virginia).[3] Grafton was a strategic point early in the American Civil War because it had a terminal for the B&O Railroad.[11][Note 3] The regiment was initially tasked with duty protecting the nearby communities of Philippi, Beverly and Webster.[13][Note 4] On May 23, Brigadier General William W. Averell took command of the brigade, relieving Brigadier General Benjamin S. Roberts. Averell's 4th Separate Brigade had one cavalry regiment, three mounted infantry regiments, two infantry regiments, a cavalry battalion, and two batteries.[16][Note 5]

Early action

On July 2, 1863, a Union command was attacked by 1,700 Confederate soldiers and nearly surrounded near its camp in Beverly.[17] Two squadrons of the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, under the command of Major Gibson, were sent to Harris' assistance, and arrived about four miles (6.4 km) north of Beverly around 3:00 am on July 3. They surprised Confederate infantry along the Cheat River at about 8:00 am, and drove them back to a breastworks containing 4,000 men.[18] Around noon, Averell arrived with a battery and his three mounted infantry regiments, and drove the Confederate force south. More skirmishing was conducted on July 4 near Huttonville (now known as Huttonsville) as the Confederates were driven further south. Fighting ended in rain around midnight, and the Union force returned to Webster in the morning.[18]

After the Battle of Gettysburg, the regiment was involved with pursuing Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia that was retreating from Pennsylvania to Virginia. On July 4, Major Foley led a force of 300 men (including men from the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry and other regiments) that burned a Potomac River bridge and captured enemy soldiers.[19] The remaining portion of Averell's brigade boarded an eastbound train on July 8, and reported to Cumberland, Maryland.[18] On July 13, Colonel Schoonmaker led most of the regiment as it was involved with capturing one of Lee's supply wagon trains and several hundred prisoners.[20] Foley's detachment rejoined the regiment shortly after July 15.[3] On July 19, the regiment confronted Major General Jubal Early's Confederate division near Hedgesville, but retreated to Martinsburg after Early tried to move around the Union flank.[20]

Averell's raids in 1863

Averell's raid in West Virginia

On August 15, while in Petersburg in West Virginia's Hardy County, Averell received orders to retrieve law books from Lewisburg and attack a list of targets at points in between.[21][Note 6] His force for this expedition included the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, Gibson's Battalion, and other mounted regiments.[Note 7] The brigade destroyed a saltpeter works near Franklin on August 19, and drove Confederate troops commanded by Colonel William L. "Mudwall" Jackson away from Huntersville on August 22.[27][28] Moving east, the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry was involved in a skirmish near Warm Springs, Virginia, on August 24.[29] Another saltpeter works was destroyed further south on August 25.[30]

Significant fighting began on the morning of August 26 west of White Sulphur Springs when Averell's advance guard was intercepted by Confederate troops.[31] A soldier from another regiment wrote that during the battle the 14th Pennsylvania "made one of the most daring charges of the war, not only facing a murderous storm of leaden hail from the front but also, to their surprise, received an enfilading fire along their flank from a large body of infantry concealed in a cornfield...."[32] The charge was led by Colonel Schoonmaker and Captain John Bird from Company G. Bird was wounded, captured, and eventually taken to Libby Prison.[33] Schoonmaker's horse was shot but he escaped on a dead soldier's horse.[34] Over 100 men from the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry were killed, wounded, or captured in the battle—nearly half of all Union casualties.[35] Fighting ended in the morning of the next day as both sides nearly exhausted their ammunition. The battle became known as the Battle of White Sulphur Springs, and Averell was prevented from reaching Lewisburg. Pursued by Confederate troops, Averell's force struggled north using blockades, deceptions, night marches, and back roads—reaching safety on August 31.[36]

Averell's Lewisburg and railroad raid

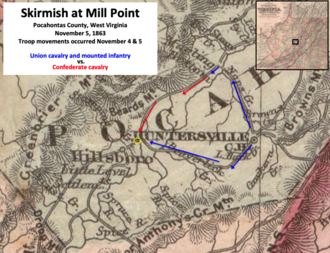

On October 23, Averell was ordered to capture, or drive away, a Confederate force stationed near Lewisburg in Greenbrier County, West Virginia. A second Union force, which was commanded by Brigadier General Alfred N. Duffié, was ordered to approach Lewisburg from another direction and provide assistance. After Lewisburg, Averell was to attack the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad if practicable, and destroy the railroad bridge over the New River.[37] Averell departed on November 1 and arrived at Huntersville on November 4.[38]

From Huntersville on November 5, Schoonmaker led the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry and 3rd West Virginia Mounted Infantry in an attempt to encircle a Confederate cavalry regiment. Schoonmaker took a southwestern route while another force took a northwestern route, but the trap failed when entrenched Confederate troops with artillery stopped Schoonmaker near Mill Point.[39] With the support of the force using the northwestern route, and later Averell with the remainder of the brigade, Schoonmaker helped drive the Confederates back to Droop Mountain.[40]

At Droop Mountain on the next day, Schoonmaker commanded a force that included the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry and most of the artillery. They created a diversion that enabled two infantry regiments to flank the Confederate mountaintop position, causing Confederate troops to be nearly surrounded before they fled south to Lewisburg.[41] When the fighting was mostly over, Gibson's Battalion was used to pursue the retreating Confederates.[41] The Confederate troops were soundly defeated, but arrived in Lewisburg before Duffié could intercept them.[42][43] The raid on the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad was called off after Averell reached Lewisburg.[44]

Salem raid

The Salem raid on the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad began on December 8, when Averell's brigade departed from New Creek (present day Keyser, West Virginia).[45] Colonel Schoonmaker was sick and hospitalized, so the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William H. Blakeley. Majors Daily and Foley were also with the regiment, and Major Gibson led his independent command. Averell's brigade for this raid consisted of his mounted regiments plus Gibson's Cavalry Battalion and Ewing's 6-gun battery.[46] The purpose of the raid was to destroy portions of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad.[47] The 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry was armed with seven-shot carbines, Colt's navy revolvers, and sabers.[48] After moving over 200 miles (320 km) in rain and snow, Averell's force reached Salem, Virginia, on December 16.[49] The brigade spent only six hours destroying railroad infrastructure because they discovered that Major General Fitzhugh Lee's Cavalry Brigade was on a train moving to Salem.[50]

Averell's brigade began the return trip by moving north through New Castle and then east to Fincastle, where the brigade arrived on December 18.[51][52] At that time, Averell split his command so it could evade at least two pursuing forces. Two Union columns, led by Averell and Lieutenant Colonel Blakeley, took obscure roads south of Covington to a bridge across the Jackson River.[52] Averell's first column was able to cross the bridge, but Blakeley's column met Confederate troops on the evening of December 19. Company A from the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry and Blakeley were in the front of the column, and they were able to cross the bridge and join Averell. The remaining portion of the column (including most of the regiment) was cut off from the bridge.[53] Fighting continued all night, and the bridge was destroyed. Confederate officers contacted the regiment's Major Foley demanding surrender, but Foley refused—and men from the regiment began shouting "the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry never surrenders".[53] A place about two miles (3.2 km) upriver was successfully used to ford the river, and Foley's assumed-captured force caught up with Averell in the Allegheny Mountains.[54][Note 8] The brigade reached the safety of Beverly on December 25.[57] Casualties for the regiment were six drowned, five wounded, and 25 captured in the attempted bridge crossing.[58]

Crook-Averell 1864 Raid on the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad

At the beginning of 1864, Averell's Brigade, including the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, had its winter quarters at Martinsburg, West Virginia.[59] Cavalry in the Department of West Virginia was reorganized multiple times in early 1864.[60] Averell was given command of the 2nd Cavalry Division, which included the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry in a brigade commanded by Colonel Schoonmaker. Brigadier General Duffié commanded the other brigade.[61] The 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry was commanded by Major John M. Daily.[62]

In April, Averell's division moved across West Virginia via the B&O Railroad and joined Brigadier General George Crook for dual raids on the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad. Averell led a small cavalry force of 2,079 men and attacked further west from Crook.[63][64] Averell abandoned an attack on a salt mine when he discovered his route to the mine was blocked by a larger force.[63] He proceeded east toward Wytheville and its lead mine.[64] On May 10, Averell's cavalry fought the inconclusive Battle of Cove Mountain. Schoonmaker's brigade started the fighting in the four-hour battle.[65] Averell's cavalry was prevented from moving through Cove Gap to Wytheville, the railroad, and a lead mine.[66] Union losses were 114 casualties.[67][68] Averell's force escaped at night over the mountains using a difficult route, and eventually destroyed 26 bridges and portions of railroad track between Christiansburg and the New River. On May 15, he linked with Crook, who had a major victory at the Battle of Cloyd's Mountain.[69]

Duncan's detachment

During the Crook-Averell Raid, a detachment of dismounted men from the regiment was left behind under the command of Captain Ashbel F. Duncan and Lieutenant Colonel Blakeley.[70] The detachment was mounted and assigned to a brigade commanded by Colonel William B. Tibbits.[71] The detachment was in the advance when the Battle of New Market started on May 15, and several men were killed and wounded—and most of their horses were killed.[72] The detachment was remounted for the Battle of Piedmont on June 5 as part of an army newly commanded by Major General David Hunter. In the battle, Duncan's men made a dismounted charge into enemy earthworks, and took prisoners.[72] On June 6, Hunter's army arrived at Staunton, Virginia, and Confederate supplies stored there were destroyed or distributed among the troops. Area workshops and factories were destroyed, and all railroad bridges and depots were destroyed.[73]

Hunter's attack on Lynchburg

Averell and Crook arrived in Staunton on June 8 as ordered by Hunter, and the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry and its detachment were reunited.[74] The cavalry was reorganized on June 9, with Duffié in command of the 1st Division and Averell in command of the 2nd Division. Schoonmaker, Colonel John H. Oley, and Colonel William Powell commanded the three brigades of the 2nd Division, respectively. Schoonmaker's Brigade consisted of the 8th Ohio Cavalry Regiment and the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry.[75] Major Daily commanded the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry.[76]

Averell's division arrived in Lexington on June 11 around noon, with the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry in the advance.[76] Schoonmaker's brigade drove away Confederate troops, including cadets from the Virginia Military Institute (a.k.a. VMI), commanded by Brigadier General John McCausland. The town was extremely hostile, and Union soldiers were shot at from the direction of buildings belonging to VMI. Hunter ordered the buildings bombed and destroyed.[77] He also relieved Schoonmaker from command because Schoonmaker did not burn VMI immediately when he took the town.[Note 9] On the next day, Hunter ordered Schoonmaker to proceed south with his brigade, and handed Schoonmaker a paper that said Hunter's treatment of Schoonmaker "had been under a misapprehension".[78] The division moved through Buchanan, across the Blue Ridge Mountains, through Liberty, and arrived at New London around dusk on June 16.[77][79]

At sunrise on June 17, Averell moved north by the old road from New London until they got four miles (6.4 km) from Lynchburg.[79] At that time, a battle began with Schoonmaker's brigade arriving first and deploying on the left of the pike. Powell's and Oley's brigades arrived next. The cavalry fought dismounted until late in the afternoon, when it was replaced by infantry and artillery.[80] Fighting continued on the next day with the cavalry back in front, although the Union forces were on the defensive instead of attacking. At dark, the regiment was surprised to learn that Schoonmaker's and Powell's brigades were the only Union troops active in the field—all other troops and wagons had already begun to fall back. The 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry was therefore the first and last Union regiment to fight in the Battle of Lynchburg.[80] The retreat was made westward, and Averell's entire division fought for two hours near Liberty until its ammunition was exhausted and it was relieved by Crook's infantry.[81] The regiment's casualties from June 10 through June 23 totaled to 27.[82] Losses for all divisions were 938.[83]

Near Winchester

Rutherford's Farm

In early July, the regiment left Charleston, West Virginia, and took a three-day train ride with their horses from Parkersburg to the rail station at Martinsburg.[84] They were part of the 1st Brigade, 2nd Cavalry Division, Army of West Virginia. The regiment, brigade, and division commanders were still the same, and Hunter was still commander of the Department of West Virginia, but Brigadier General Crook commanded the army in the field.[85][86] While portions of the Union army were still arriving in the Martinsburg area, Averell was sent from Martinsburg toward Winchester to meet a perceived threat to the B&O Railroad from Major General Jubal Early's Army of the Valley.[87] During the advance, he sent a detachment of 200 men from the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry to the west side of Winchester, and the main body of the regiment was sent east to attack Berryville. Despite being outnumbered, Averell won the Battle of Rutherford's Farm against Confederate Major General Stephen Dodson Ramseur. The 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry did not participate in the fighting.[88]

Kernstown

Averell occupied Winchester, and Crook arrived on July 22 and assumed command. Most of the army camped on the south side of town, not far from Kernstown. On July 24, Averell was ordered to conduct a flanking maneuver (Crook's left, Confederate right) near the Front Royal road to cut off what Crook believed was a small band of Confederates.[89] By 11:00 am, Schoonmaker's brigade began the maneuver as the advance.[90] Schoonmaker discovered a huge Confederate force trying to turn the Union left flank.[91] Soon Averell's force of 1,500 men had 3,000 Confederate infantry men from the division of Major General Robert E. Rodes on the right and 2,200 Confederate cavalrymen from Brigadier General John C. Vaughn's Division on the left.[92] While Crook's infantry was falling back, the infantry of Rodes tried to cut off Averell from the rest of Crook's army. Rodes' men on foot could not outrace Averell's cavalry, but they did cause a panic—especially Schoonmaker's brigade that had absorbed the brunt of the initial attack.[92] Union forces retreated through Winchester, continued across the Potomac River, and finally stopped at Hagerstown, Maryland. The Second Battle of Kernstown was a major defeat for Crook, and a victory for Early with attached forces.[93] Union casualties were 1,185 killed, wounded or missing; including 13 for the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry.[94]

Chambersburg and Moorefield

During late July and early August, Colonel Schoonmaker was running a camp for dismounted cavalry in Pleasant Valley, Maryland.[95] Its purpose was to remount and re-equip men from the division. A detachment of 212 men from the camp, led by Lieutenant Colonel Blakeley, assisted Brigadier General Wesley Merritt's division in August. The detachment returned to camp around mid-August, and Blakeley was badly injured from being thrown from his horse.[96] The remaining portion of the regiment was with Averell, who was stationed in Hagerstown and had troops guarding nearby fords along the Potomac River. Averell had only 1,260 men and two pieces of artillery in his command.[97] Major Gibson, who had been leading an independent cavalry battalion, returned to the regiment, and was assigned command of the 1st Brigade. Captain Kerr was assigned command of the regiment.[98]

After Early's victory in the Second Battle of Kernstown, he moved his infantry to Martinsburg and his cavalry deployed along the Potomac River. He sent two cavalry brigades north commanded by McCausland and Bradley Johnson, with McCausland having overall command. They crossed the Potomac River west of Williamsport, Maryland on July 29, assisted by diversionary crossings at other locations by Brigadier General John D. Imboden and "Mudwall" Jackson.[99] The Union force nearest to McCausland belonged to Averell, and his communications were cut around noon on that day.[100]

Chambersburg

On July 30, McCausland burnt the town of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, and then moved west and rested his horses. The 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, commanded by Major Gibson, entered the town's main street too late to save anything.[101] Moving west on the McConnellsburg Turnpike, Averell skirmished with the Confederate rear guard for about an hour near McConnellsburg. McCausland moved past Bedford to Hancock in Maryland, where he demanded a ransom to spare the town from being burned. While the people of the town were raising the ransom, Gibson and the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry attacked without Averell's main column. Later near the evening, Averell's full force attacked and drove McCausland toward Cumberland.[102] Averell's actions may have prevented the burning of Hancock in Maryland, and McConnellsburg and Bedford in Pennsylvania.[103]

McCausland had been able to secure fresh horses, leaving none for Averell and causing Averell to pause in his pursuit in Hancock.[104] Averell rested his horses and troops until August 3, when he received an order from General David Hunter to pursue McCausland and attack "wherever found".[105] He moved on the next day. Averell's force received food for his men and horses at Springfield, West Virginia, north of Romney. He learned that McCausland was moving south toward Moorefield.[105] Averell also received 500 reinforcements, increasing his force to 1,760 men.[106] McCausland's cavalry had about 3,000 men plus a battery of four guns.[107] McCausland set up camp in West Virginia on the pike where it crosses the South Branch Potomac River between Romney and Moorefield. His brigade camped on the south side of the river, while Bradley Johnson's Brigade camped on the north side.[108]

Moorefield

Averell arrived in Romney, around 11:00 am on August 6. At that time he sent a battalion of men from the 22nd Pennsylvania Cavalry away from the main road to block McCausland's route east back to the Shenandoah Valley.[109] Averell's main force continued south at 1:00 am on August 7. The force was led by a group of scouts dressed in Confederate uniforms, followed by the main force far enough behind that it could not be detected. The scouts were led by Captain Kerr of the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry.[110] Kerr selected his men for the mission, and most were from Company C or D. They moved forward on foot in darkness and fog.[107] At about 2:30 am, Kerr's scouts began deceiving and capturing various squads of pickets posted along the main road.[111]

Early in the morning, about 60 of Kerr's men wearing Confederate uniforms entered Johnson's camp and calmly moved further south past the Confederate 1st Maryland Cavalry. Then Gibson's Brigade, including the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, attacked Johnson's surprised men, and captured more than they could control. Johnson himself was captured, but escaped after being sent to the rear unrecognized.[112][113] Kerr was shot in the face and thigh, and his horse killed—yet he captured the flag of the 8th Virginia Cavalry and rode away on the color bearer's horse.[114] McCausland's Brigade, camped south of the river, had some warning of the attack. However, Powell's 2nd Brigade and the battalion from the 22nd Pennsylvania Cavalry thoroughly dispersed and scattered Confederate resistance. Averell captured 27 officers and 393 enlisted men, 4 artillery pieces, and 400 horses. The Confederate killed and wounded was unknown. Union losses were 7 killed and 21 wounded.[115] A Union soldier from Powell's Brigade estimated that the "loss to the enemy in killed, wounded and captured was near eight hundred".[116] Captain Thomas R. Kerr, of the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, was awarded the Medal of Honor.[117]

Shenandoah Valley

In mid-August, Major General Philip Sheridan reorganized his cavalry. Brigadier General Alfred Torbert was made commander of the Cavalry Corps. Averell was made commander of the 2nd Division, with Schoonmaker and Powell as his brigade commanders. Schoonmaker's 1st Brigade of cavalry regiments consisted of the 14th Pennsylvania, 22nd Pennsylvania, and 8th Ohio. The 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry would now be fighting in the Shenandoah Valley as part of a large army.[118]

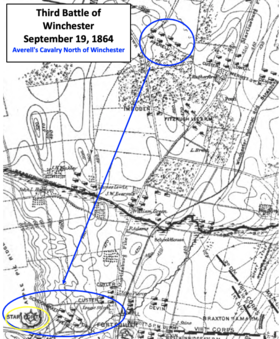

Third Battle of Winchester

On September 19, Sheridan's army of 40,000 men defeated Early's army of 15,000 men in the Third Battle of Winchester (a.k.a. the Battle of Opequon Creek). One division of Union cavalry and two corps of infantry attacked from the east, while Averell's cavalry and an additional cavalry division attacked from the north.[119] Major Foley had been wounded earlier in the month, so Captain Ashbel F. Duncan led the regiment.[120][121] Almost all of the regiment's fighting occurred north of Winchester. Summarizing the battle, Confederate General Early wrote that his army "deserved the victory, and would have had it, but for the enemy's immense superiority in cavalry, which alone gave it to him".[122]

Close to the edge of Winchester, Averell ordered Schoonmaker's brigade to capture Star Fort, which stood on a hill on the northwest side of town. The fort had a well-supported battery, and the brigade's first charge was unsuccessful.[123] A new line of about 300 men from the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry was formed and led by Captain Duncan, who attempted to capture the fort's guns while another portion of the regiment moved around the flank of the enemy. While this was happening, Schoonmaker was notified that Duncan had been killed while partially up the hill. Schoonmaker hurried up the hill to lead in person, and found the badly–wounded Duncan still alive and mounted. Duncan finally received a fatal wound while his men overran the earth works. The regiment captured one of the Confederate cannons and about 300 men while the rest of the Confederates fled before they were surrounded.[124] Duncan was shot seven times, and was carried off the field to die.[121] Captain William W. Miles became the regiment's commander.[125] The 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry had 14 of the 19 casualties for Schoonmaker's brigade.[126] Schoonmaker was later awarded the Medal of Honor for the capture of the fort.[127]

Fisher's Hill

The Battle of Fisher's Hill occurred on September 21–22, 1864. Sheridan's army again defeated Early's army. The battle took place further south of Winchester near the Valley Pike, slightly south of Strasburg, Virginia.[128] In this battle, Schoonmaker's brigade attacked the front of the Confederate left while Crook's Army of West Virginia flanked the Confederate left using a concealed approach from North Mountain.[129] Early's men fled south in disorder, and were pursued by the other half of Averell's division, Powell's brigade.[130] Casualties were light for the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, one man wounded of the brigade's total of two.[131] After the battle, Sheridan pressured his commanders to pursue Early's retreating army, and became impatient with Averell. On September 23, Averell was replaced with Powell, who took command on the next day.[132] Averell chose two companies from the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, Companies A and H, to escort him to Winchester.[133] Powell's division moved south to Mount Jackson.[134]

Weyer's Cave and the Burning

Following the Battle of Fisher's Hill, the two armies continued south along the pike. Major Daily commanded the regiment while Schoonmaker commanded the 1st Brigade. Lieutenant Colonel Blakeley was in Pittsburgh for a court martial case, Major Gibson was under arrest, and Major Foley was still in a hospital for his wounds. Early was pursued up the valley through New Market, and eventually eastward as he moved toward Port Republic and Brown's Gap.[135] Powell's division patrolled the areas around Harrisonburg, Mount Crawford, and Staunton.[136]

The division arrived at Weyer's Cave in the afternoon of September 26, and Schoonmaker's brigade crossed the South River and attacked enemy cavalry. The brigade drove the Confederate cavalry east until it encountered infantry and artillery. Fighting until dark, the brigade returned to Weyer's Cave on the west side of the river.[137] On the morning of September 27, a Confederate artillery shell flew through Schoonmaker's headquarters and exploded harmlessly beyond it. The 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry was quickly formed in line and charged the enemy. Soon it was discovered that they were fighting as many as five Confederate divisions, and the regiment was driven back. The regiment contested its position so well that the Adjutant General of Pennsylvania ordered them to have an inscription on their regimental battle flag that read: "Weyer's Cave September 27th 1864 For Gallantry in Battle."[138]

Near the close of the skirmish at Weyer's Cave, Major General George Armstrong Custer arrived to succeed Powell as commander of the division. Early's army moved to Staunton and Waynesboro. The division moved to Port Republic where it camped, and Powell turned over command to Custer. Most of Sheridan's army fell back to Cedar Creek and Harrisonburg.[139] For the next two weeks, much of the farming infrastructure and food between Harrisonburg and Staunton was destroyed by detachments from Sheridan's Army.[140] Custer's 2nd Division, including the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, was among those assigned with this task.[141] On September 30, Custer was transferred to command the 3rd Cavalry Division, and Powell returned to command the 2nd Cavalry Division.[142] Sheridan reported on October 7 that "I have destroyed over 2,000 barns filled with wheat, hay and farming implements; over 70 mills, filled with flour and wheat; have driven in front of the army over 4,000 head of stock, and have killed and issued to the troops not less than 3,000 sheep."[140]

Cedar Creek

On October 3, a picket post composed of 44 men from the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry were captured near Mount Jackson. The remainder of the regiment was stationed near Cedar Creek.[143] The Battle of Cedar Creek started with a surprise attack for Early's Army in the early morning hours of October 19, 1864.[144] Early struck the Union Army's left flank where the only Union cavalry nearby was the 1st Cavalry Brigade from Powell's Division. The brigade was composed of three cavalry regiments: the 14th and 22nd Pennsylvania, and the 8th Ohio.[145] The 1st Cavalry Brigade was commanded by Colonel Alpheus Moore of the 8th Ohio Cavalry, and Major Gibson commanded the regiment.[146] The 14th Pennsylvania was awakened before daylight when pickets from the 8th Ohio Cavalry galloped into camp with Confederate cavalry following them and screaming the rebel yell. During the morning fighting, the "officer in command of the brigade" (Colonel Moore) refused to dismount his men to support the division of Brigadier General Thomas Devin.[147] The battle appeared to be a defeat for the Union until General Sheridan arrived and rallied his troops for a Union victory.[148][144] Only one soldier from the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry was wounded.[149] After the battle, Colonel Moore was placed under arrest, and Major Gibson became commander of the 1st Brigade.[150]

Luray Valley

Nineveh

Beginning November 10, the 21st New York Cavalry Regiment was assigned to the 1st Brigade of Powell's 2nd Division. Colonel William B. Tibbits, from the 21st New York Cavalry, was assigned to command the 1st Brigade, relieving Major Gibson. Colonel Moore was released from arrest and directed to command his regiment, the 8th Ohio Cavalry.[150] Separately, Major John M. Daily was dismissed for absence without leave effective November 11, but reinstated seven months later as a lieutenant colonel.[151][152] The 2nd Division fought Major General Lunsford L. Lomax's cavalry on November 12 near Nineveh, Virginia. Powell sent Tibbits with his 1st Brigade out beyond Front Royal, where it encountered cavalry commanded by McCausland.[153] The Confederates slowly pushed the 1st Brigade back, but Powell brought his 2nd Brigade to the front while the 1st Brigade moved to the rear.[154] The 2nd Brigade charged, resulting in a short clash that ended with the Confederates retreating for 8 miles (12.9 km).[155] All of the Confederate artillery (two guns), two caissons, two wagons and an ambulance were captured. Confederate casualties were 20 killed, 35 wounded, and 161 captured including 19 officers. Prisoners said McCausland was slightly wounded and escaped through the woods. Union losses were two killed and 15 wounded.[153][Note 10]

Mosby

Powell's Division skirmished near Rude's Hill for about six hours on November 23. Afterwards, it went into camp between Front Royal and Winchester.[158] While cooking turkeys on Thanksgiving Day (November 24), the regiment was attacked by Mosby's guerrillas.[159][Note 11] Mosby was quickly chased off by the regiment, and ten of Mosby's men were killed or wounded.[159]

Major Gibson was assigned command of the 1st Brigade on December 7.[160] A few weeks later on December 17, Captain William Miles of Company I led 100 men on a scouting expedition toward Ashby's Gap.[161] Mosby ambushed this scouting party from a woods near Millwood, Virginia, killing Miles and about a dozen others. About 20 others were wounded, and nearly everybody else was captured. Mosby set one man free after slashing his face with a saber, allowing him to return to camp to tell the story of the ambush. The wounded and dead were recovered on the next day.[159] Mosby sent his prisoners to Libby Prison.[162]

Winter 1864-1865 and war's end

Winter

The regiment's winter camp was located in Winchester. On December 19, the regiment participated in a failed expedition to Gordonsville that was expected to capture the town and enable portions of the Virginia Central Railroad to be destroyed.[163] The organization of Sheridan's Middle Military Division at the end of 1864 had Powell in command of the 2nd Cavalry Division, Tibbits in command of the division's 1st Brigade, and Schoonmaker in command of the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry.[164] Lieutenant Colonel Blakeley, who had been dismissed, was restored to commission.[165][Note 12] The final expedition of the winter began on February 19, 1865, and ended with Major Gibson and his men ambushed by Mosby between Ashby's Gap and the Shenandoah River. Gibson's horse was shot and fell on him, although he was eventually able to find another horse and escape. Gibson's loss was one officer wounded, and 80 men missing.[167][168]

Fighting ends

The regiment left winter camp on April 4, and moved up the Shenandoah Valley. Major Foley resigned on April 6.[169] Confederate General Lee surrendered at Appomattox on April 9, and the regiment was ordered to Washington on April 20. For the next month, they camped in Virginia at Arlington, Fairfax Court House, and Alexandria.[170] The men of the regiment whose term of enlistment expired prior to October 1, 1865, mustered out in late May and early June.[171] Lieutenant Colonel Blakeley resigned effective June 6.[169] The remainder of the regiment was consolidated into six companies and left Washington on June 11 on a B&O Railroad train. They arrived in Fort Leavenworth in Kansas on June 28, and the reinstated Major Daily was promoted to lieutenant colonel on that day.[169] Most of the men mustered out on July 31, including Colonel Schoonmaker. On August 5, Company A escorted General Grenville M. Dodge on a trip across the plains. The remaining men other than Company A were mustered out on August 24. Company A, after returning from its western plains trip, mustered out on November 2.[171]

The regiment began its fighting in Beverly, West Virginia, on July 3, 1863. Its last fight was at Ashby's Gap on February 19, 1865. In between, members of the regiment fought in nearly 90 skirmishes and battles.[172] In 31 of those engagements, the regiment suffered casualties.[173] The regiment had two medal of honor winners, and two of its men commanded brigades.[174] During the war, the regiment lost 2 officers and 97 enlisted men killed or mortally wounded. Disease resulted in the death of 296 enlisted men.[13]

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ The commonwealth (state) of Pennsylvania had a "confusing numbering system" for its American Civil War regiments.[6] Each regiment received two designations. One number reflected the order, regardless of branch, of when the regiment was raised. In the case of the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment, they were the 159th regiment of any military branch raised in Pennsylvania. The second number, 14th Cavalry in this case, corresponded to the regiment's integration into the Federal armed force.[6]

- ^ The spelling of Lieutenant Colonel William H. Blakeley's surname used herein is "Blakeley", which matches the spelling in his 1899 obituary and additional sources.[7][1][8] Other sources, including the regimental historian and Averell, have spelled it as "Blakely".[4][9]

- ^ The Union Army used the B&O Railroad to haul soldiers and supplies—making it a target for the Confederate Army. In southwestern Virginia, the Virginia Central Railroad and the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad were among the railroads important to the Confederacy for similar reasons.[12]

- ^ Philippi, West Virginia, which was part of Virginia in early 1863, was spelled as "Phillippa" on some maps of that time, and the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry historian spells it as "Phillipi".[14][15]

- ^ Averell's brigade consisted of the following regiments: 10th West Virginia Infantry, 28th Ohio Infantry, 2nd West Virginia Mounted Infantry, 3rd West Virginia Mounted Infantry, 8th West Virginia Mounted Infantry, and the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry. Other units were Company A of the 1st West Virginia Cavalry, Company C of the 3rd West Virginia Cavalry, 3rd Independent Company Ohio Cavalry, Company C of the 16th Illinois Cavalry, Battery B of the 1st West Virginia Artillery (six guns), and Battery G of the 1st West Virginia Artillery (four guns).[16]

- ^ At the time, Petersburg was part of Hardy County. In 1866, a western portion of Hardy County was split into a new county named Grant, and Petersburg became the county seat of the new county.[22]

- ^ Averell's force consisted of the 3rd and 8th West Virginia Mounted Infantries, the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, Ewing's Battery, and Gibson's Cavalry Battalion.[23] Gibson's Battalion included three companies (F, H, and I) from the 3rd West Virginia Cavalry Regiment, Company C from the 16th Illinois Cavalry Regiment (a.k.a. Chicago Dragoons), the 3rd Independent Company of Ohio Cavalry, and Company A of the 1st West Virginia Cavalry Regiment (a.k.a. Kelley Lancers)[24][25][26]

- ^ A Pennsylvania newspaper says Blakeley remained with the regiment.[55] The historian of the 5th West Virginia Cavalry (formerly 2nd West Virginia Mounted Infantry) says "Blakely brought up the rear with his regiment", but when describing the river fording mentions "Major Daily's command" and "Major Daily and his men".[56] Reverend Slease of Company C of the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, when discussing the 14th "never surrenders" in his book, says "The friends of Lieut. Col. Blakely ascribed it to him. It is certain it was not he, for he, with Co. A., was already on the opposite side of the river."[53]

- ^ Schoonmaker being relieved started rumors that he was arrested because he refused to burn VMI. That was not true—he followed orders to have VMI burned, but not as soon as he entered the town.[78]

- ^ The historian of the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry gave an account of the battle differs from Powell's report. In his version, the 2nd Brigade was sent out first as a decoy, only to retreat. Then Schoonmaker's 1st Brigade, concealed behind a hill, attacked the Confederates and drove them back while capturing 325 officers and men. Conflicting with the regimental historian's version, two men from the 2nd Brigade received the Medal of Honor for capturing enemy battle flags. Both men were in the 1st West Virginia Cavalry, Private James F. Adams and Sergeant Levi Shoemaker.[156][157]

- ^ The historian of the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry wrote that probably "no regiment in the Civil War had more encounters with Mosby or lost so many killed and wounded or captured by Mosby".[159]

- ^ Blakeley was hospitalized after being thrown from his horse on August 12. While in the hospital, his detachment left its post, causing his dismissal. The general in charge did not know Blakeley was in the hospital. After a petition from officers in the regiment, and with a letter from Major General Torbert saying the recommendation for dismissal came under misapprehension of the facts, Blakeley was reinstated December 14.[166]

Citations

- ^ a b Bates 1869, p. 851

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, pp. 16–17

- ^ a b c d [Unlisted] 1908, p. 470

- ^ a b c Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 16

- ^ United States Adjutant-General's Office 1865, p. 784

- ^ a b Gibbs 2002, p. 1869

- ^ Breck 1899, p. 137

- ^ "Soldier Details - Blakeley, William". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2021-06-28. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 926

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 18

- ^ "Grafton, West Virginia - Our History". City of Grafton. Archived from the original on 2021-05-15. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- ^ Whisonant 2015, p. 157

- ^ a b "Union Pennsylvania Volunteers - 14th Regiment, Pennsylvania Cavalry (159th Volunteers)". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2021-05-14. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- ^ Alvin Jewett Johnson (1864). Johnson's Virginia, Delaware, Maryland & West Virginia (Map). New York, New York: Johnson and Ward (Library of Congress). Archived from the original on 2020-10-30. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 83

- ^ a b Scott 1889, p. 209

- ^ "From the Tenth Va. Regiment -- Bill Jackson's Attack on Beverly (p.2 col.3)". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). 1863-07-17. Archived from the original on 2021-05-16. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ a b c Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 84

- ^ Wittenberg, Petruzzi & Nugent 2008, Ch.8

- ^ a b Slease & Gancas 1999, pp. 85–86

- ^ Scott 1890, pp. 38–39

- ^ "CCAWV - Grant County". County Commissioners' Association of West Virginia. Archived from the original on 2021-05-10. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- ^ Scott 1890, pp. 33–35

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 33

- ^ "1st Regiment, West Virginia Cavalry". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2021-05-14. Retrieved 2021-05-18.

- ^ "3rd Regiment, West Virginia Cavalry". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2021-05-13. Retrieved 2021-05-18.

- ^ Reader 1890, p. 203

- ^ ""Mudwall" Jackson, described by historian Eric J. Wittenberg". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-07-06.

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 42

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 34

- ^ Scott 1890, pp. 34–35

- ^ Reader 1890, p. 205

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 54

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 91

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 41

- ^ Starr 2007, p. 160

- ^ Scott 1890, pp. 499–502

- ^ Lowry 1996, p. 61

- ^ Lowry 1996, p. 70

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 518

- ^ a b Scott 1890, p. 521

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 500

- ^ Lowry 1996, p. 105

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 504

- ^ Starr 2007, p. 166

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, pp. 113–114

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 920

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 114

- ^ Reader 1890, p. 225

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 118

- ^ Reader 1890, p. 226

- ^ a b Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 120

- ^ a b c Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 121

- ^ Reader 1890, p. 228

- ^ "The Heroism (bottom of page 2)". American Citizen - Butler, Pennsylvania (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). 1864-01-20. Archived from the original on 2021-07-12. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ Reader 1890, pp. 227–228

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 919

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 932

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 126

- ^ Starr 2007, p. 212

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 127

- ^ Barnes, D.M. (1864-06-10). "Gen. Averill'S Operations; Spirited Account of the Great Southern Virginia Raid. Its Object—Destruction of Railroads, Bridges and Medical Stores—A Gallant and Obstinate Fight—Gen. Averill Wounded—Incidents". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- ^ a b Scott 1891, p. 41

- ^ a b Sutton 2001, pp. 113–114

- ^ Scott 1891, p. 43

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 115

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 116

- ^ "Virginia Center for Civil War Studies - Wytheville". Virginia Center for Civil War Studies, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Archived from the original on 2021-04-17. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- ^ Scott 1891, p. 12

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 134

- ^ Scott 1891, p. 77

- ^ a b Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 132

- ^ Scott 1891, p. 95

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, pp. 136–139

- ^ Scott 1891, pp. 145–146

- ^ a b Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 139

- ^ a b Slease & Gancas 1999, pp. 139–140

- ^ a b Slease & Gancas 1999, pp. 149–150

- ^ a b Scott 1891, p. 147

- ^ a b Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 142

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 130

- ^ Scott 1891, p. 105

- ^ Scott 1891, p. 106

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 138

- ^ Scott 1891, p. 286

- ^ Scott 1891b, p. 10

- ^ Patchan 2007, p. 119

- ^ Patchan 2007, pp. 137–138

- ^ Patchan 2007, p. 227

- ^ Patchan 2007, p. 188

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 155

- ^ a b Patchan 2007, p. 228

- ^ "Second Battle of Kernstown". American Battlefield Trust. Archived from the original on 2023-01-05. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

- ^ Scott 1891, p. 290

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902b, p. 738

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902b, p. 797

- ^ Patchan 2007, p. 330

- ^ Mowrer 1899, p. 21

- ^ Pond 1912, p. 101

- ^ Pond 1912, p. 102

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 158

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 159

- ^ Pond 1912, p. 104

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 148

- ^ a b Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 493

- ^ Patchan 2007, p. 290

- ^ a b Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 160

- ^ Patchan 2007, p. 292

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 494

- ^ Patchan 2007, p. 296

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 149

- ^ Patchan 2007, p. 299

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 495

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 161

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 3

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 150

- ^ "Thomas R. Kerr". Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Archived from the original on 2021-07-13. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 175

- ^ "Third Battle of Winchester". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2021-05-02. Retrieved 2021-06-23.

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 177

- ^ a b Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 185

- ^ Early & Early 1912, pp. 426–427

- ^ Farrar 1911, p. 377

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 239

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 111

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 117

- ^ "James M. Schoonmaker". Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Archived from the original on 2021-06-08. Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- ^ "FISHER'S HILL". American Battlefield Trust. Archived from the original on 2021-06-25. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 191

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 161

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 124

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 505

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 194

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 198

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, pp. 198–199

- ^ Davis, Perry & Kirkley 1893a, pp. 506–507

- ^ Farrar 1911, p. 392

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, pp. 199–200

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 201

- ^ a b "The Burning - The Shenandoah Valley in Flames". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2021-06-28. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 202

- ^ Farrar 1911, p. 400

- ^ Davis, Perry & Kirkley 1893a, p. 514

- ^ a b "Overview of the Battle of Cedar Creek". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-06-30.

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 206

- ^ Davis, Perry & Kirkley 1893a, p. 130

- ^ Davis, Perry & Kirkley 1893a, p. 478

- ^ Davis, Perry & Kirkley 1893a, p. 137

- ^ Davis, Perry & Kirkley 1893a, p. 136

- ^ a b Davis, Perry & Kirkley 1893b, p. 595

- ^ [Unlisted] 1864, p. 202

- ^ Pennsylvania General Assembly 1866, p. 458

- ^ a b Davis, Perry & Kirkley 1893a, p. 512

- ^ Beach 1902, pp. 448–449

- ^ Beach 1902, p. 450

- ^ "U.S. Civil War - U.S. Army - James F. Adams". Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-07-01.

- ^ "U.S. Civil War - U.S. Army - Levi Shoemaker". Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-07-01.

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 218

- ^ a b c d Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 219

- ^ Davis, Perry & Kirkley 1893b, p. 753

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 259

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 260

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999

- ^ Davis, Perry & Kirkley 1893b, p. 854

- ^ [Unlisted] 1864, p. 283

- ^ "Lieut. Col. Blakely, 14th Pa. Cavalry (right side of page 2)". American Citizen - Butler, Pennsylvania (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). 1865-01-25. Archived from the original on 2021-07-12. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 261

- ^ Davis, Perry & Kirkley 1894, p. 466

- ^ a b c Bates 1869, p. 858

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, pp. 283–285

- ^ a b Slease & Gancas 1999, pp. 286–288

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, Supplement p. 121-123

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, pp. 289–291

- ^ "Search For Medals of Honor - 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

References

- Ainsworth, Fred C.; Kirkley, Joseph W., eds. (1902). The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Additions and Corrections to Series I Volume XLIII Part 1. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 427057. Archived from the original on 2023-02-12. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- Ainsworth, Fred C.; Kirkley, Joseph W., eds. (1902b). The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Additions and Corrections to Series I Volume XLIII Additions and Corrections. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 427057.

- Bates, Samuel P. (1869). History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5: Prepared in Compliance with Acts of the Legislature. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer. OCLC 1887553. Archived from the original on 2023-02-12. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- Beach, William Harrison (1902). The First New York (Lincoln) Cavalry from April 19, 1861, to July 7, 1865. New York: Lincoln Cavalry Association. p. 448. OCLC 44089779.

Nineveh Powell chased.

- Breck, E.Y., ed. (1899). Pittsburgh Legal Journal (p.137). Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: John S. Murray. Archived from the original on 2023-02-12. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- Davis, George B.; Perry, Leslie J.; Kirkley, Joseph W. (1893a). The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XL Part I Reports, Correspondence, Etc. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-91867-807-2. OCLC 12241509. Archived from the original on 2023-02-12. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- Davis, George B.; Perry, Leslie J.; Kirkley, Joseph W. (1893b). The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XLIII Part II Correspondence, Etc. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-91867-807-2. OCLC 12241509. Archived from the original on 2023-02-12. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- Davis, George B.; Perry, Leslie J.; Kirkley, Joseph W. (1894). The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XLV1 Part I Reports. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-91867-807-2. OCLC 12241509. Archived from the original on 2023-02-12. Retrieved 2021-07-03.

- Early, Jubal A.; Early, Ruth H. (1912). Lieutenant General Jubal Anderson Early, C.S.A. Autobiographical Sketch and Narrative of the War Between the States. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: J.B. Lippincott Co. ISBN 978-1-46819-215-5. OCLC 1370161. Archived from the original on 2023-02-12. Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- Farrar, Samuel Clarke (1911). The Twenty-Second Pennsylvania Cavalry and the Ringgold Battalion. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: New Werner Company. ISBN 9781275494534. OCLC 1018148044. Archived from the original on 2023-02-12. Retrieved 2021-06-24.

- Gibbs, Joseph (2002). Three Years in the "Bloody Eleventh": The Campaigns of a Pennsylvania Reserves Regiment. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-27102-166-9. OCLC 248759378.

- Lowry, Terry (1996). Last Sleep: The Battle of Droop Mountain, November 6, 1863. Charleston, West Virginia: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-57510-024-1. OCLC 36488613.

- Mowrer, George H. (1899). History of the Organization and Service, During the War of the Rebellion, of Company A, 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry. Survivor's Association. OCLC 228711541. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- Patchan, Scott C. (2007). Shenandoah Summer: The 1864 Valley Campaign. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-0700-4. OCLC 122563754.

- Pennsylvania General Assembly (1866). Miscellaneous Documents, Read in the Legislature of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, during the Session which Commenced at Harrisburg on the 2nd Day of January, 1866 - Vol. II. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Singerly & Myers, State Printers. OCLC 228664952. Archived from the original on 2023-02-12. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- Pond, George E. (1912). The Shenandoah Valley in 1864. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. OCLC 13500039.

- Reader, Frank S. (1890). History of the Fifth West Virginia Cavalry, Formerly the Second Virginia Infantry, and of Battery G, First West Virginia Light Artillery. New Brighton, Pennsylvania: Daily News, Frank S. Reader, Editor and Proprietor. Retrieved 2021-04-05.

- Scott, Robert N., ed. (1889). The War of the Rebellion : A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I – Volume XXVII Part II. Washington: Government Printing Office. OCLC 318422190. Archived from the original on 2023-02-12. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- Scott, Robert N., ed. (1890). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXIX Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved 2021-03-23.

- Scott, Robert N., ed. (1891). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- Scott, Robert N., ed. (1891b). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part II. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 427057. Archived from the original on 2023-02-12. Retrieved 2021-07-03.

- Slease, William Davis; Gancas, Ron (1999) [1915]. The Fourteenth Pennsylvania Cavalry in the Civil War: A History of the Fourteenth Pennsylvania Volunteer Cavalry from its Organization until the Close of the Civil War, 1861-1865. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Soldiers' & Sailors' Memorial Hall and Military Museum. ISBN 978-0-96449-529-6. OCLC 44503009.

- Starr, Stephen Z. (2007). The Union Cavalry in the Civil War - Vol. 2 - The War in the East, from Gettysburg to Appomattox. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. OCLC 4492585.

- Sutton, Joseph J. (2001) [1892]. History of the Second Regiment, West Virginia Cavalry Volunteers, During the War of the Rebellion. Huntington, WV: Blue Acorn Press. ISBN 978-0-9628866-5-2. OCLC 263148491.

- United States Adjutant-General's Office (1865). Official Army Register of the Volunteer Force of the United States Army for the Years 1861, '62, '63, '64, '65 (Part III). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 686779. Archived from the original on 2023-02-12. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- [Unlisted] (1864). The United States Army and Navy Journal and Gazette of the Regular and Volunteer Forces - Vol. II 1864-65. New York, New York: Publication Office Number 39 Park Row. OCLC 3157857. Archived from the original on 2023-02-12. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- [Unlisted] (1908). The Union Army; A History of Military Affairs in the Loyal States, 1861-65 — Records of the Regiments in the Union Army — Cyclopedia of Battles — Memoirs of Commanders and Soldiers — Volume I. Madison, Wisconsin: Federal Publishing Company. OCLC 1473658. Archived from the original on 2023-02-12. Retrieved 2021-05-14.

- Whisonant, Robert C. (2015). Arming the Confederacy : How Virginia's Minerals Forged the Rebel War Machine. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-319-14508-2. OCLC 903929889.

- Wittenberg, Eric J. (2011). The Battle of White Sulphur Springs: Averell Fails to Secure West Virginia. Charleston, South Carolina: History Press. ISBN 978-1-61423-326-8. OCLC 795566215.

- Wittenberg, Eric J.; Petruzzi, J. David; Nugent, Michael F. (2008). One Continuous Fight: the Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit of Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, July 4–14, 1863. New York: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-9327144-3-2. OCLC 185031178.