102nd Division (Philippines)

| 102nd Infantry Division | |

|---|---|

| Cagayan sector force | |

| Active | 15 March – 10 May 1942 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | Army |

| Type | Infantry Division |

| Role | Territorial Defense |

| Size | 4,713 Infantry |

| Part of | Mindanao Force (March 1942 - May 1942) |

| Garrison/HQ | Tankulan, Bukidnon |

| Engagements | World War II |

| Commanders | |

| Commander | Col. William P. Morse |

| Executive Officer | LCol. Arden Boellner |

| Chief of Staff | LCol. Wade D. Killen |

| Staffs | Quartermaster - Maj. Orville Hunter Chaplain - Fr. Edralin |

| WWII Philippine Army Divisions | ||||

|

The 102nd Infantry Division was a division of the Philippine Army under the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE).

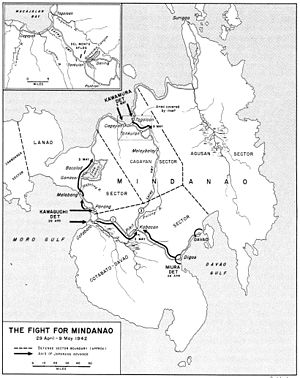

Organized in early 1942, the division was responsible for the defense of the Cagayan Sector of Mindanao. It fought in the defense of Mindanao against Japanese invasion in early May, and surrendered after the Fall of Corregidor during the Philippines Campaign of 1941–1942.

History

Organization

The 61st and 81st Field Artillery Regiments were relocated by ship to Cagayan from Panay and Negros, respectively, between 2 and 3 January 1942. The movement was part of a large scale relocation of troops from the Visayas to Mindanao in order to strengthen the defenses of the latter. The 61st transferred from the 61st Division and the 81st from the 81st Division.[1] The 61st and 81st Field Artillery were organized and equipped as infantry, due to the lack of artillery.[2] On 12 January, United States Army Infantry Colonel William P. Morse was assigned commander of the Cagayan Sector of the Mindanao Force portion of the Visayan-Mindanao Force, including both regiments.[3] Major General William F. Sharp commanded the Visayan-Mindanao Force. The Cagayan Sector was responsible for the defense of the northern terminus of the Sayre Highway, one of the island's two highways, and its only heavy bomber airfield, Del Monte.[2]

They still had few if any items of heavy equipment, but had manpower and some rifles. Soon after the assignment of sectors to the 61st and 81st Field Artillery, Major Reed Graves' 1st Battalion, 101st Infantry reduced the 81st Field Artillery sector by taking over positions west from Tinao Canyon to the Little Agusan River. Around a week later the battalion was transferred south and replaced by the 3rd Philippine Constabulary Regiment, which took over the area from the Cagayan River to Barrio Gusa. The constabulary unit was in turn relieved by the 103rd Infantry, less 2nd Battalion, around 15 February.[4]

The formation of the 102nd Division from the troops of the Cagayan Sector under the command of Morse was authorized by Douglas MacArthur when he passed through Mindanao during his escape to Australia in mid-March,[5] by USAFFE General Order No. 43 on 15 March. Its 102nd Engineer Battalion was organized from personnel of the Surigao Provisional Battalion, while men from the Agusan Provisional Battalion and 2nd Provisional Battalion (Cotabato) were used to form the Headquarters Company, Service Troops and the 102nd Maintenance and Quartermaster Companies.[6] Due to a shortage of ammunition, the untrained Filipino soldiers of the division were not able to conduct live fire exercises, and had never fired their outmoded Enfield rifles, instead spending hours practicing simulated firing.[7]

In order to defend against an anticipated amphibious landing at Macajalar Bay against the Sayre Highway, Morse positioned the division along its shores between the Tagoloan and Cagayan Rivers. The 81st Field Artillery, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel John P. Woodbridge, reinforced by a 65-man detachment composed of ground personnel-turned-infantrymen from the 30th Bombardment Squadron that had been left at Del Monte when their squadron departed for Australia, held a four-mile sector from the Tagaloan to the Sayre Highway. The four miles to the west, extending from the highway to the Cugman River, were held by Colonel Hiram W. Tarkington's 61st Field Artillery, while Major Joseph R. Webb's 103rd Infantry guarded the remainder of the line to the Cagayan.[8]

About 1 May, the division numbered 4,713 men, including nineteen American officers, 67 American enlisted men (65 from the Air Corps detachment and two in the 61st Field Artillery), 268 Filipino officers, and 4,359 Filipino enlisted men. The 103rd Infantry was the strongest with nearly 1,800 personnel, while the 61st and 81st Field Artillery numbered slightly more than 1,000.[9]

Japanese invasion of Mindanao

On the afternoon of 2 May, the 102nd Division was alerted for combat after the convoy carrying the Kawamura Detachment, the Japanese invasion force for the Cagayan Sector, was spotted by a reconnaissance aircraft north of Macajalar Bay. The convoy entered the bay during the night, precipitating execution of the previously prepared demolition plan. The Japanese began simultaneous landings at Cagayan and at Tagoloan about 01:00 on 3 May, supported by the fire of two destroyers from the convoy. By dawn, the Japanese firmly held the shoreline between Tagoloan and the Sayre Highway. Although Webb was unable to prevent the Cagayan landing, he launched a two-company counterattack against the beachhead. In his subsequent report to Sharp, Webb stated that he might have been able to repulse the Japanese if he had not been forced to retreat when his right flank was exposed by the retreat of the 61st Field Artillery.[8]

Battle of Mangima Canyon

In response to the Japanese landing, Sharp moved his reserves, which were the 2.95-inch gun detachment of Major Paul D. Phillips, the 62nd Infantry of Lieutenant Colonel Allen Thayer, and the 93rd Infantry of Major John C. Goldtrap, forward. The 2.95-inch gun detachment and the 93rd Infantry took up blocking positions on the Sayre Highway in the evening, as the 62nd Infantry moved up behind them. At 16:00 Morse ordered a general withdrawal, under the cover of darkness, to positions astride the highway about six miles south of the beach, but this was never effected due to a conference between Sharp, Morse, Woodbridge, and Webb. Instead, the commanders decided to defend along a line parallel to the Mangima Canyon and River east of Tankulan, where the Sayre Highway briefly separated into an upper and lower road, in order to block the Sayre Highway and prevent a Japanese advance into central Mindanao.[8]

Sharp issued his orders for the withdrawal at 23:00. The Dalirig Sector on the upper (northern) road was held by the 102nd Division with the 62nd Infantry, 81st Field Artillery, the 2.95-inch gun detachment, and Companies C and E of the 43rd Infantry (PS), under Morse's command. The former commander of the Mindanao Force Reserve, Colonel William F. Dalton, took command of the Puntian Sector on the lower (southern road) with the 61st Field Artillery and the 93rd Infantry. Separated by the Japanese advance, the 103rd Infantry was made independent, tasked with defending the Cagayan River valley.[8]

All units reached the positions by the morning of 4 May, taking advantage of a lull in the Japanese advance to organize the line for the rest of that day and the next. The division's 62nd Infantry held the main line of resistance along the east wall of Mangima Canyon, closely supported by the 2.95-inch gun detachment, while the reserve, Companies C and E of the 43rd Infantry (PS), was stationed in Dalirig itself. The remnants of the 81st Field Artillery, reduced to 200 men, were stationed in a draw 500 yards behind the town.[8]

The Kawamura Detachment resumed its advance on 6 May, reaching Tankulan by the end of the day and registering artillery on Dalirig. On the next day, accurate Japanese artillery fire and air attack targeted the 62nd Infantry, whose left battalion suffered the most, forcing Thayer to reinforce the line with his reserve battalion. The bombardment continued until 19:00 on 8 May, when the Japanese infiltrated the division's lines, sowing disorder. In the chaos two platoons "mysteriously received orders to withdraw" and retreated, but were quickly stopped as no such orders had actually been issued. Before they could return to the front they came under attack from a small force of Japanese infiltrators, after which other Filipino troops commenced firing, although they could not distinguish between friend and foe in the night, inducing further panic on the line. The firing was only halted after Thayer's personal intervention.[8]

After holding through the night, the 62nd Infantry, "tired and disorganized", retreated towards Dalirig by the morning of 9 May. The 2.5-inch gun detachment retreated, leaving the two Philippine Scout companies as the last organized resistance in the sector. At 11:30, as the 62nd retreated through the town, the Japanese attacked them on three sides, turning the retreat into a rout. The two Scout companies held their positions, but were forced to withdraw when threatened with encirclement. The Dalirig forces fled over exposed terrain, discarding equipment as they progressed under small arms, artillery fire, and strafing. By the end of the 9 May the Dalirig Sector forces no longer existed, except for the 150 men of the 2.5-inch gun detachment, holding positions five miles to the east of the town.[10]

Surrender

Sharp surrendered his command on 10 May, following the Fall of Corregidor,[11] having ordered the 102nd Division units in the Dalirig Sector at 21:30 on 9 May to surrender at daybreak.[12] Including the 103rd Infantry, the division surrendered sixteen American officers and four enlisted men, as well as eighty Filipino officers and 622 enlisted men. The remainder were listed as missing in action. Three American officers, seven Filipino officers, and 166 Filipino enlisted men from the 62nd Infantry surrendered, while only the two American officers of the two 43rd Infantry companies surrendered.[13] The surrendered personnel of the division were sent to the former 101st Division camp at Malaybalay, along with the other surrendered personnel of the Visayas-Mindanao Force.[14]

The 102nd Division personnel who remained unsurrendered simply disappeared into the hills of Mindanao; many later fought in the Philippine resistance against Japan.[15]

Order of battle

Earlier Period (before 3 May 1942)

- Headquarters, 102nd Division (PA)

- 62nd Infantry Regiment (PA) (LCol Allen Thayer) (transferred from 61st Infantry Division from Panay)

- 103rd Infantry Regiment (PA) (Major Joseph R. Webb) (transferred from the 101st Division)

- 61st Field Artillery Regiment (PA)(Col. Hiram Tarkington)(transferred from 61st Infantry Division from Panay)

- 81st Field Artillery Regiment (PA) (LCol John Woodridge)(transferred from Cebu Force)

- Headquarters Company, 102nd Division (PA)

- Headquarters, Special Troops, 102nd Division (PA)

- 102nd Maintenance Company (PA)

- 102nd Quartermaster Service Company (PA)

- 102nd Engineer Battalion (PA)

- Company A, 101st Medical Battalion (PA)[9]

Later Period (4–10 May 1942)

The following units were included in the 102nd Division from the retreat to Dalirig to the surrender:

- 103rd Infantry Regiment (PA) - Major Joseph Webb

- 3rd Battalion - Major Robert Bowler

- 62nd Infantry Regiment (PA) (Lieutenant Colonel Allen Thayer)

- 81st Field Artillery Regiment (LCol John Woodridge)

- QF 2.95-inch Gun Detachment (Major Paul D. Phillips)

- Provisional Battalion, 43rd Infantry (PS) (Major Allen L. Peck)

- Company "C", 43rd Infantry (PS)

- Company "E", 43rd Infantry (PS)[8]

- Headquarters Company, 102nd Division (PA)

- Headquarters, Special Troops, 102nd Division (PA)

- 102nd Maintenance Company (PA)

- 102nd Quartermaster Service Company (PA)

- 102nd Engineer Battalion (PA)

- Company A, 101st Medical Battalion (PA)[9]

- 93rd Infantry Regiment - Major John Goldtrap (attached to the division in April 1942)

- 3rd PC Regiment (attached to the division in February 1942 but transferred to Agusan sector in April 1942)

Notables Members

- Hiram Tarkington

- John Lewis

- Joseph Webb

- William P. Morse

- Arden Boellnel

- John Woodridge

- Rosauro Prusia Dongallo, Governor of Misamis Oriental 1974 - 1979

- Jose Doromal Docdocil

- Leonardo V. Hernando,

- Ernest E. McClish

References

Citations

- ^ Sharp 1946, pp. 27–28.

- ^ a b Morton 1953, pp. 516–517.

- ^ Sharp 1946, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Tarkington, p. 81.

- ^ Braddock 1946, p. 554.

- ^ Sese 1947, p. 24.

- ^ Tarkington, pp. 345, 429.

- ^ a b c d e f g Morton 1953, pp. 516–518.

- ^ a b c Sharp 1946, pp. 29–30, 75–76.

- ^ Morton 1953, pp. 518–519.

- ^ Morton 1953, p. 576.

- ^ Tarkington, p. 397.

- ^ Morse 1942, pp. 352–354.

- ^ Braddock 1946, p. 565.

- ^ Schmidt 1982, p. 72.

See also

Bibliography

- Morton, Louis (1953). United States Army in World War II, The War in the Pacific: The Fall of the Philippines. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Schmidt, Major Larry S. (1982). American Involvement in the Filipino Resistance Movement on Mindanao During the Japanese Occupation, 1942–1945 (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014.

Unpublished sources

- Sese, Alfredo C. (1947). Notes on the Philippine Army, 1941–1942. – Compiled from official documents by the History Section, G-2, Headquarters, Philippine Army

- Sharp, William F. (1946). Historical Report, Visayan-Mindanao Force, Defense of the Philippines, 1 September 1941-10 May 1942. (Annex XI, Report of Operations of USAFFE and USFIP in the Philippine Islands, 1941-1942)

- Braddock, William H. (1946). "Report of the Force Surgeon, Visayas-Mindanao Force, USAFFE and USFIP". Historical Report, Visayan-Mindanao Force, Defense of the Philippines, 1 September 1941-10 May 1942.

- Morse, William P. (1942). "Record of Action and Events, Headquarters 102nd Division". Historical Report, Visayan-Mindanao Force, Defense of the Philippines, 1 September 1941-10 May 1942.

- Tarkington, Hiram W. There Were Others. – Unpublished memoirs of the 61st Field Artillery commander