Moai

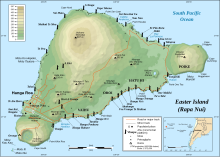

Moai or moʻai (/ˈmoʊ.aɪ/ ⓘ MOH-eye; Spanish: moái; Rapa Nui: moʻai, lit. 'statue') are monolithic human figures carved by the Rapa Nui people on Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in eastern Polynesia between the years 1250 and 1500.[1][2] Nearly half are still at Rano Raraku, the main moai quarry, but hundreds were transported from there and set on stone platforms called ahu around the island's perimeter. Almost all moai have overly large heads, which account for three-eighths of the size of the whole statue. They also have no legs. The moai are chiefly the living faces (aringa ora) of deified ancestors (aringa ora ata tepuna).[3]

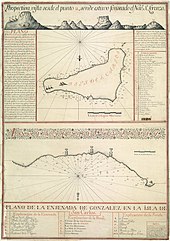

The statues still gazed inland across their clan lands when Europeans first visited the island in 1722, but all of them had fallen by the latter part of the 19th century.[4] The moai were toppled in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, possibly as a result of European contact or internecine tribal wars.[5]

The production and transportation of the more than 900 statues[6][7] is considered a remarkable creative and physical feat.[8] The tallest moai erected, called Paro, was almost 10 metres (33 ft) high and weighed 82 tonnes (81 long tons; 90 short tons).[9][10] The heaviest moai erected was a shorter but squatter moai at Ahu Tongariki, weighing 86 tonnes (85 long tons; 95 short tons). One unfinished sculpture, if completed, would be approximately 21 m (69 ft) tall, with a weight of about 145–165 tonnes (143–162 long tons; 160–182 short tons).[11] Statues are still being discovered as of 2023.[12]

Description

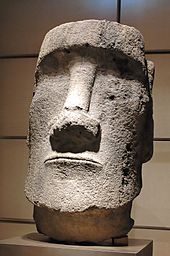

The moai are monolithic statues, and their minimalist style reflects forms found throughout Polynesia. Moai are carved from volcanic tuff (solidified ash). The human figures would be outlined in the rock wall first, then chipped away until only the image was left.[13] The over-large heads (a three-to-five ratio between the head and the trunk, a sculptural trait consistent with the Polynesian belief in the sanctity of the chiefly head) have heavy brows and elongated noses with a distinctive fish-hook-shaped curl of the nostrils. The lips protrude in a thin pout. Like the nose, the ears are elongated and oblong in form. The jaw lines stand out against the truncated neck. The torsos are heavy, sometimes, the clavicles are subtly outlined in stone too. The arms are carved in bas relief and rest against the body in various positions, hands and long slender fingers resting along the crests of the hips, meeting at the hami (loincloth), with the thumbs sometimes pointing towards the navel. Generally, the anatomical features of the backs are not detailed, but sometimes bear a ring and girdle motif on the buttocks and lower back. Except for one kneeling moai, the statues do not have clearly visible legs.

Though moai are whole-body statues,[14] they are often referred to as "Easter Island heads" in some popular literature. This is partly because of the disproportionate size of most moai heads, and partly because many of the images for the island showing upright moai are of the statues on the slopes of Rano Raraku, many of which are buried to their shoulders, which has led to a popular misconception that they don't have bodies.[15][16] Some of the "heads" at Rano Raraku have been excavated and their bodies seen, and observed to have markings that had been protected from erosion by their burial. [citation needed]

The average height of the moai is about 4 m (13 ft), with the average width at the base around 1.6 m (5.2 ft). These massive creations usually weigh around 12.5 tonnes (13.8 tons) each.

All but 53 of the more than 900 moai known to date were carved from tuff (a compressed volcanic ash) from Rano Raraku, where 394 moai in varying states of completion are still visible today. There are also 13 moai carved from basalt, 22 from trachyte and 17 from fragile red scoria.[17] At the end of carving, the builders would rub the statue with pumice.

Characteristics

Easter Island statues are known for their large, broad noses and big chins, along with rectangle-shaped ears and deep eye slits. Their bodies are normally squatting, with their arms resting in different positions and are without legs. The majority of the ahu are found along the coast and face inland towards the community. There are some inland ahu such as Ahu Akivi. These moai face the community but given the small size of the island, also appear to face the coast.[11]

Eyes

In 1979, Sergio Rapu Haoa and a team of archaeologists discovered that the hemispherical or deep elliptical eye sockets were designed to hold coral eyes with either black obsidian or red scoria pupils.[18] The discovery was made by collecting and reassembling broken fragments of white coral that were found at the various sites. Subsequently, previously uncategorized finds in the Easter Island museum were re-examined and recategorized as eye fragments. It is thought that the moai with carved eye sockets were probably allocated to the ahu and ceremonial sites, suggesting that a selective Rapa Nui hierarchy was attributed to the moai design until its demise with the advent of the religion revolving around the tangata manu.

Symbolism

Many archaeologists suggest that "[the] statues were thus symbols of authority and power, both religious and political. However, they were not only symbols. To the people who erected and used them, they were actual repositories of sacred spirit. Carved stone and wooden objects in ancient Polynesian religions, when properly fashioned and ritually prepared, were believed to be charged by a magical spiritual essence called mana."[19]

Archaeologists believe that the statues were a representation of the ancient Polynesians' ancestors. The moai statues face away from the ocean and towards the villages as if to watch over the people. The exception is the seven Ahu Akivi which face out to sea to help travelers find the island. There is a legend that says there were seven men who waited for their king to arrive.[20] A study in 2019 concluded that ancient people believed that quarrying of the moai might be related to improving soil fertility and thereby critical food supplies.[21]

Pukao topknots and headdresses

The more recent moai had pukao on their heads, which represent the topknot of the chieftains. According to local tradition, the mana was preserved in the hair. The pukao were carved out of red scoria, a very light rock from a quarry at Puna Pau. Red itself is considered a sacred color in Polynesia. The added pukao suggest a further status to the moai.[22]

Markings

When first carved, the surface of the moai was polished smooth by rubbing with pumice. However, the easily worked tuff from which most moai were carved is easily eroded, such that the best place to see the surface detail is on the few moai carved from basalt or in photographs and other archaeological records of moai surfaces protected by burials.[citation needed]

Those moai that are less eroded typically have designs carved on their backs and posteriors. The Routledge expedition of 1914 established a cultural link[23] between these designs and the island's traditional tattooing, which had been repressed by missionaries a half-century earlier. Until modern DNA analysis of the islanders and their ancestors, this was key scientific evidence that the moai had been carved by the Rapa Nui and not by a separate group from South America.[citation needed]

At least some of the moai were painted. One moai in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art was decorated with a reddish pigment.[24] Hoa Hakananai'a was decorated with maroon and white paint until 1868, when it was removed from the island.[25][26] It is now housed in the British Museum, London, but demands have been made for its return to Rapa Nui.[27]

History

The statues were carved by the aboriginal Polynesians of the island, mostly between 1250 and 1500.[1] In addition to representing deceased ancestors, the moai, once they were erected on ahu, may also have been regarded as the embodiment of powerful living or former chiefs and important lineage status symbols. Each moai presented a status: "The larger the statue placed upon an ahu, the more mana the chief who commissioned it had."[22] The competition for grandest statue was ever prevalent in the culture of the Easter Islanders. The proof stems from the varying sizes of moai.[22]

Completed statues were moved to ahu mostly on the coast, then erected, sometimes with pukao, red stone cylinders, on their heads. Moai must have been very time-consuming to craft and transport; not only would the actual carving of each statue require effort and resources, but the finished product was then hauled to its final location and erected.

The quarries in Rano Raraku appear to have been abandoned abruptly, with a litter of stone tools and many completed moai outside the quarry awaiting transport and almost as many incomplete statues still in situ as were installed on ahu. In the nineteenth century, this led to conjecture that the island was the remnant of a sunken continent and that most completed moai were under the sea. That idea has long been debunked, and now it is generally believed that:

- Some statues were rock carvings and never intended to be completed.

- Some were incomplete because, when inclusions were encountered, the carvers would abandon a partial statue and start a new one.[28] Tuff is a soft rock with occasional lumps of much harder rock included in it.

- Some completed statues at Rano Raraku were placed there permanently and not parked temporarily awaiting removal.[29]

- Some were indeed incomplete when the statue-building era came to an end.

Craftsmen

It is not known exactly which group in the communities were responsible for carving statues. Oral traditions suggest that the moai were carved either by a distinguished class of professional carvers who were comparable in status to high-ranking members of other Polynesian craft guilds, or, alternatively, by members of each clan. The oral histories show that the Rano Raraku quarry was subdivided into different territories for each clan.

Transportation

Since the island was largely treeless by the time the Europeans first visited, the movement of the statues was a mystery for a long time. Study of fossil pollen and charcoal traces found in sediment cores collected in the island's three main crater lakes suggest that forests that originally covered the island were gradually logged between 800 and 1200 CE (as the island was being settled by migrants from eastern Polynesia), then again in the decades or centuries before 1700.[30]

It is not exactly known how the moai were moved across the island, however, there are numerous studies and theories discussing the topic. Earlier researchers assumed that the process required human energy, ropes, and possibly wooden sledges (sleds) or rollers, as well as leveled tracks across the island (the "Easter Island roads"). Another theory suggests that the moai were placed on top of logs and were rolled to their destinations.[31] If that theory is correct, it would take 50–150 people to move the moai.[citation needed] The most recent study demonstrates from the evidence in the archaeological record that the statues were harnessed with ropes from two sides and made to "walk" by tilting them from side to side while pulling forward, in a vertical way.[4][7][32][33]

Oral histories recount how various natives used divine power to command the statues to walk. The earliest accounts say a king named Tuu Ku Ihu moved them with the help of the god Makemake, while later stories tell of a woman who lived alone on the mountain ordering them about at her will. Scholars currently support the theory that the main method was that the moai were "walked" upright (some assume by a rocking process), as laying it prone on a sledge (the method used by the Easter Islanders to move stone in the 1860s) would have required an estimated 1500 people to move the largest moai that had been successfully erected. In 1998, Jo Anne Van Tilburg suggested fewer than half that number could do it by placing the sledge on lubricated rollers. In 1999, she supervised an experiment to move a nine-tonne moai. A replica was loaded on a sledge built in the shape of an A frame that was placed on rollers and 60 people pulled on several ropes in two attempts to tow the moai. The first attempt failed when the rollers jammed up. The second attempt succeeded when tracks were embedded in the ground. This was on flat ground and used eucalyptus wood rather than the native palm trees.[34]

In 1986, Pavel Pavel, Thor Heyerdahl and the Kon-Tiki Museum experimented with a five-tonne moai and a nine-tonne moai. With a rope around the head of the statue and another around the base, using eight workers for the smaller statue and 16 for the larger, they "walked" the moai forward by swiveling and rocking it from side to side; however, the experiment was ended early due to damage to the statue bases from chipping. Despite the early end to the experiment, Thor Heyerdahl estimated that this method for a 20-tonne statue over Easter Island terrain would allow 320 feet (100 m) per day. Other scholars concluded that it was probably not the way the moai were moved due to the reported damage to the base caused by the "shuffling" motion.[34][35]

Around the same time, archaeologist Charles Love experimented with a 10-tonne replica. His first experiment found rocking the statue to walk it was too unstable over more than a few hundred yards. He then found that placing the statue upright on two sled runners atop log rollers, 25 men were able to move the statue 150 feet (46 m) in two minutes. In 2003, further research indicated this method could explain supposedly regularly spaced post holes (his research on this claim has not yet been published) where the statues were moved over rough ground. He suggested the holes contained upright posts on either side of the path so that as the statue passed between them, they were used as cantilevers for poles to help push the statue up a slope without the requirement of extra people pulling on the ropes and similarly to slow it on the downward slope. The poles could also act as a brake when needed.[36]

Based on detailed studies of the statues found along prehistoric roads, archaeologists Terry Hunt and Carl Lipo have shown that the pattern of breakage, form and position of statues is consistent with an upright hypothesis for transportation.[4] Hunt and Lipo argue that when the statues were carved at a quarry, the sculptors left their bases wide and curved along the front edge. They showed that statues along the road have a center of mass that causes the statue to lean forward. As the statue tilts forward, it rocks sideways along its curved front edge and takes a step. Large flakes are seen broken off the sides of the bases. They argue that once the statue was walked down the road and installed in the landscape, the wide and curved base was carved down.[37]

Terry Hunt of UH Manoa and Carl Lipo of California State University Long Beach have worked closely with Rapa Nui archaeologist Sergio Rapu to develop their theory of how the Rapa Nui people rope walked the moai. It was through their successful moai walking recreation that it was proven that it is fully possible that the moai were literally walked from their quarries to their final positions by ingenious use of ropes. Teams of workers would have worked to rock the moai back and forth, creating the walking motion and holding the moai upright.[32][38] If correct, it can be inferred that the fallen road moai were the result of the teams of balancers being unable to keep the statue upright, and it was presumably not possible to lift the statues again once knocked over.[39] However, the debate continues.[40]

Birdman cult

Originally, Easter Islanders had a paramount chief or single leader.[citation needed] Through the years the power levels veered from sole chiefs to a warrior class known as matatoʻa. The therianthropic figure of a half bird and half-man was the symbol of the matatoʻa; the distinct character connected the sacred site of Orongo. The new cult prompted battles of tribes over worship of ancestry. Creating the moai was one way the islanders would honor their ancestors; during the height of the birdman cult there is evidence which suggests that the construction of moai stopped.

"One of the most fascinating sights at Orongo are the hundreds of petroglyphs carved with birdman and Makemake images. Carved into solid basalt, they have resisted ages of harsh weather. It has been suggested that the images represent birdman competition winners. Over 480 birdman petroglyphs have been found on the island, mostly around Orongo."[41] Orongo, the site of the cult's festivities, was a dangerous landscape which consisted of a "narrow ridge between a 1,000-foot (300 m) drop into the ocean on one side and a deep crater on the other". Considered the sacred spot of Orongo, Mata Ngarau was the location where birdman priests prayed and chanted for a successful egg hunt. "The purpose of the birdman contest was to obtain the first egg of the season from the offshore islet Motu Nui. Contestants descended the sheer cliffs of Orongo and swam to Motu Nui where they awaited the coming of the birds. Having procured an egg, the contestant swam back and presented it to his sponsor, who then was declared birdman for that year, an important status position."[42]

Moai Kavakava

These figures are much smaller than the better-known stone moai. They are made of wood and have a small, slender aspect, giving them a sad appearance. These figures are believed to have been made after the civilization on Rapa Nui began to collapse, which is why they seem to have a more emaciated appearance to them.[43]

1722–1868 toppling of the moai

In years after the arrival in 1722 of Jacob Roggeveen, all of the moai that had been erected on ahu were toppled; some last standing statues were reported in 1838 by Abel Aubert du Petit-Thouars, but none remained by 1868,[44] apart from the partially buried ones on the outer slopes of Rano Raraku.

Oral histories include an account of a clan pushing down a single moai in the night, but others tell of the "earth shaking", and there are indications that at least some of them fell down due to earthquakes.[45] Some of the moai toppled forward such that their faces were hidden, and often fell in such a way that their necks broke; others fell off the back of their platforms.[45] Today, about 50 moai have been re-erected on their ahus or at museums elsewhere.[46]

The Rapa Nui people were devastated by raids of slave traders who visited the island in 1862. Within a year, the individuals who remained on the island were sick or injured, and lacking leadership. The survivors of the slave raids had new company from missionaries, who converted the remaining populace to Christianity. Native Easter Islanders began to be assimilated, as their tattoos and body paint were banned by the new Christian proscriptions, and they were subjected to removal from a portion of their native lands and made to reside on a much smaller portion of the island, while the rest was used for farming by the Peruvians.

Removal of moai from Easter Island

Ten or more moai have been removed from Easter Island and transported to locations around the world, including the ones today displayed at the Louvre Museum in Paris and the British Museum in London.

Replicas and casts

Several other locations displays replicas (casts) of moai, including the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County; the Auckland Museum;[47] the American Museum of Natural History;[48] and the campus of the American University.[49]

Preservation and restoration

From 1955 to 1978, an American archaeologist, William Mulloy, undertook extensive investigation of the production, transportation and erection of Easter Island's monumental statuary. Mulloy's Rapa Nui projects include the investigation of the Akivi-Vaiteka Complex and the physical restoration of Ahu Akivi (1960); the investigation and restoration of Ahu Ko Te Riku and Ahu Vai Uri and the Tahai Ceremonial Complex (1970); the investigation and restoration of two ahu at Hanga Kio'e (1972); the investigation and restoration of the ceremonial village at Orongo (1974) and numerous other archaeological surveys throughout the island.

The Rapa Nui National Park and the moai were included in the 1972 UN convention concerning the protection of the world's cultural and natural heritage[citation needed] and consequently on the 1995 list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[50]

The statues have been mapped by a number of groups over the years, including efforts by Father Sebastian Englert and Chilean researchers.[51][52] The EISP (Easter Island Statue Project) conducted research and documentation on many of the moai on Rapa Nui and the artifacts held in museums overseas. The purpose of the project is to understand the figures original use, context, and meaning, with the results being provided to the Rapa Nui families and the island's public agencies that are responsible for conservation and preservation of the moai. Other studies include work by Britton Shepardson,[53]Terry L. Hunt and Carl P. Lipo.[54]

In 2008, a Finnish tourist chipped a piece off the ear of one moai. The tourist was fined $17,000 in damages and was banned from the island for three years.[55][56]

In 2020, an unoccupied truck rolled into a moai, destroying the statue and causing 'incalculable damage'.[57]

In 2022, an unknown number of moai in Rano Raraku were damaged by a wildfire that covered an area of around 150 to 250 acres. The Mayor of Rapa Nui, Pedro Edmunds Paoa, stated the fire was started intentionally. Other authorities believe the damage to some of the affected statues is "irreparable".[58][59]

- Moai on Easter Island, a painting by William Hodges, 1775–76

Unicode character

In 2010, moai was included as a "moyai" emoji (🗿) in Unicode version 6.0 under the code point U+1F5FF as "Japanese stone statue like Moai on Easter Island".[60]

The official Unicode name for the emoji is spelt "moyai" as the emoji actually depicts the moyai statue near Shibuya Station in Tokyo.[61] The statue was a gift from the people of Nii-jima (an island 163 kilometres (101 mi) from Tokyo but administratively part of the city) inspired by Easter Island moai. The name of the statue was derived by combining "moai" and the dialectal Japanese word moyai (催合い) 'helping each other'.

As the Unicode adopted proprietary emoji initially used by Japanese mobile carriers in the 1990s,[62] inconsistent drawings were adopted for this emoji by various companies with proprietary emoji images, depicting either a moai or the moyai statue.[63] The Google and Microsoft emoji initially resembled the moyai statue in Tokyo; however, the emoji were later revised to resemble moai.[63]

Notwithstanding its intended purpose, the emoji is commonly used in Internet culture as a meme to represent a deadpan expression or used to convey that something is being said in a particularly sarcastic fashion.[64]

See also

- Marae, the Polynesian ceremonial sites from which the moai and ahu traditions likely evolved.

- Tiki, carvings of the legendary first man among the Māori and other Western Polynesian cultures

- Anito, ancestor spirits and deities of the Filipino people, often carved into wooden or stone figures

- Taotao Mona, ancestor spirits of the Chamorro people in Micronesia

- Chemamull, large funerary statues of the Mapuche of South America

- Dol hareubang, large ancient stone statues on Jeju Island, South Korea

- List of largest monoliths

Notes

- ^ a b Steven R Fischer. The island at the end of the world. Reaktion Books 2005 ISBN 1-86189-282-9

- ^ The island at the end of the world. Reaktion Books 2005 ISBN 1-86189-282-9

- ^ Van Tilburg, Jo Anne. "Easter Island Statue Project". Eisp.org. Archived from the original on 7 July 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ a b c Hunt, Terry; Lipo, Carl (2012). The Statues That Walked: Unraveling the Mystery of Easter Island. Free Press. ISBN 978-1-4391-5031-3.

- ^ Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed by Jared Diamond

- ^ "Easter Island Statue Project". Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ a b Lipo, Carl P.; Hunt, Terry L.; Haoa, Sergio Rapu (2013). "The 'Walking' Megalithic Statues (Moai) of Easter Island". J. Archaeol. Sci. 40 (6): 2859. Bibcode:2013JArSc..40.2859L. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.09.029.

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage Centre (29 May 2009). "Rapa Nui National Park". Whc.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ Young, Emma (26 July 2006). "Easter Island: A monumental collapse?". Newscientist.com. pp. 30–34. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ Van Tilburg, Jo Anne (5 May 2009). "Moai Paro digital reconstruction". Easter Island Statue Project (eisp.org). Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ a b "NOVA Online | Secrets of Easter Island | Stone Giants". Pbs.org. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ "New Easter Island moai statue discovered in volcano crater". The Guardian. 1 March 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ "What are Moai?". Thinkquest (discontinued). Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ Cascone, Sarah (1 May 2015). "Apparently Easter Island's Heads Have Bodies". Artnet News. Archived from the original on 2 December 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ Mikkelson, David (14 May 2012). "Do Easter Island Heads Have Bodies?". Snopes. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Solly, Meilan (8 April 2019). "Norway Will Repatriate Thousands of Artifacts Taken From Easter Island". Smithsonian. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Van Tilburg, Jo Anne (1994). Easter Island: Archaeology, Ecology and Culture. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0714125046. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ Ford, Nick (15 December 2013). "Views on the origin and purpose of the Easter Island statues". Archived from the original on 30 June 2014.

- ^ "Easter Island". Sacred Sites: World Pilgrimage Guide. Archived from the original on 13 February 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "Mystery of the Easter Island Statues." Red Ice Creations. N.p., 27 October 2011. Web. 30 October 2013.

- ^ Sarah C. Sherwood; Jo Anne Van Tilburg; Casey R. Barrier; Mark Horrocks; Richard K. Dunn; José Miguel Ramírez-Aliaga (2019). "New excavations in Easter Island's statue quarry: Soil fertility, site formation and chronology". Journal of Archaeological Science. 111: 104994. Bibcode:2019JArSc.111j4994S. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2019.104994. S2CID 210318823.

- ^ a b c "The Rise & Fall of Easter Island's Culture. Sentinels in Stone". Bradshaw Foundation. 2011. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ Routledge 1919, p. 220.

- ^ Kjellgren, E.; Van Tilburg, J.A.; Kaeppler, A.L. (2001). Splendid Isolation: Art of Easter Island. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-58839-011-0. Archived from the original on 14 January 2022. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Horley, P; Lee, G (2008). "Rock art of the sacred precinct at Mata Ngarau, 'Orongo". Rapa Nui Journal. 22 (2): 112–14.

- ^ Pitts 2014, pp. 39–48.

- ^ "Easter Island governor begs British Museum to return Moai: 'You have our soul'". The Guardian. 20 November 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ Routledge 1919, p. 181.

- ^ Routledge 1919, p. 186.

- ^ "Investigación con participación UdeC refuta teoría del ecocidio en Isla de Pascua: cortaron árboles por sequía". Noticias UdeC (in Spanish). 26 April 2023. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ The human figures would be outlined in the rock wall first, then chipped away until only the image was left.[6]

- ^ a b Bloch, Hannah (July 2012). "Easter Island: The riddle of the moving statues". National Geographic. 222 (1). National Geographic Society: 30–49. Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ Unsolved Mysteries: The Secret of Easter Island Archived 21 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine a test of walking the statues

- ^ a b History channel "Mega Movers: Ancient Mystery Moves"

- ^ Easter Island – the mystery solved. Thor Heyerdahl 1989

- ^ Flenley, John (2003). The Enigmas of Easter Island: Island on the Edge. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280340-5.

- ^ Terry Hunt, Carl Lipo. "The Statues Walked – What Really Happened on Easter Island – the Long Now". Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ Mystery of Easter Island (TV Documentary). NOVA and National Geographic Television. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ "Easter Island Statues Could Have 'Walked' Into Position". Wired. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ^ Ghose, Tia (7 June 2013). "Easter Island's 'Walking' Stone Heads Stir Debate". LiveScience. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ "Mysterious Places: Explore Sacred Sites and Ancient Civilizations." Mysterious Places: Explore Sacred Sites and Ancient Civilizations. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 October 2013.

- ^ "Easter Island – Moai Statues and Rock Art of Rapa Nui." The Birdman Motif of Easter Island. N.p., n.d. 29 October 2013.

- ^ F. Forment; D. Huyge; H. Valladas (2001). "AMS 14C age determinations of Rapanui (Easter Island) wood sculpture: moai kavakava ET 48.63 from Brussels". Antiquity. 75 (289): 529–32. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00088748. S2CID 163659013. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- ^ J. Linton Palmer (1870). "A visit to Easter Island, or Rapa Nui, in 1868". Journal of the Royal Geographical Society. 40: 167–81. doi:10.2307/1798641. JSTOR 1798641. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ a b Edmundo Edwards; Raul Marchetti; Leopoldo Dominichetti; Oscar Gonzales-Ferran (1996). "When the Earth Trembled, the Statues Fell". Rapa Nui Journal. Vol. 10, no. 1. pp. 1–15.

- ^ Terry L. Hunt & Carl P. Lipo (2011). The Statues That Walked:Unraveling the Mystery of Easter Island. Free Press.

- ^ "Auckland Museum - Moai replica". Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ "American Museum of Natural History - Moai cast". Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ "Welcome to American University, Washington, DC USA". Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ "Rapa Nui National Park". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Cristino, F., C., P. Vargas C., and R. Izaurieta S. (1981). Atlas Arqueológico de Isla de Pascua. Santiago: Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo, Instituto de Estudios, Universidad de Chile.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Riquelme, S., F., R. I. San Juan, I. R. Kussner, L. G. Nualart, and P. V. Casanova (1991). Teoria de las Proporciones. Generación de la Forma y procesos de Realización en la Escultura Megalítica de Isla de Pascua Sistema de Medidas en el Diseño Pascuense.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Britton Shepardson (2010). "Moai Database – Rapa Nui". Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- ^ Carl Lipo & Terry Hunt (2011). "Rapa Nui Database". Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ "Easter Island fines ear chipper". BBC News. 9 April 2008. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- ^ "Tourist chips earlobe off ancient statue on Easter Island". Globe and Mail. 9 April 2008. Archived from the original on 13 April 2008. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- ^ "Truck Crashes Into an Easter Island Statue". The NY Times. 6 March 2020. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ "Easter Island: Sacred statues damaged by wild fire". BBC News. 7 October 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ Hernandez, Joe (7 October 2022). "The iconic Easter Island statues have been damaged in a fire, authorities say". NPR. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ "The Unicode Standard, 13.0 – Miscellaneous Symbols and Pictographs" (PDF). Unicode. p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ "Moyai Statue (Shibuya) – All You Need To Know Before You Go (with Photos)". TripAdvisor. Archived from the original on 11 November 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ "EZweb絵文字一覧 【タイプD】" (PDF). KDDI au 技術情報. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ a b "🗿 Moyai Emoji". Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ Crilly, Eileanor. "Gen-Z Has Adopted The 🗿 As Their Latest Reaction Emoji, But What Does It Mean?". Trillmag. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

References

- Heyerdahl, Thor. Skjølsvold, Arne. Pavel Pavel. The "Walking" Moai of Easter Island. Retrieved 8 August 2005.

- McCall, Grant (1995). "Rapanui (Easter Island)". Pacific Islands Year Book 17th Edition. Fiji Times. Retrieved 8 August 2005.

- Matthews, Rupert (1988). Ancient Mysteries. Wayland Publishing. ISBN 0-531-18246-0.

- Pelta, Kathy (2001). Rediscovering Easter Island. Lerner Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8225-4890-4.

- Pitts, Mike (May 2014). "Hoa Hakananai'a, an Easter Island statue now in the British Museum, photographed in 1868" (PDF). Rapa Nui Journal. 28 (1). Easter Island Foundation: 39–48. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- Routledge, Katherine (1919). The Mystery of Easter Island: The Story of an Expedition. 2nd ed. London – via Internet Archive.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Van Tilburg, Jo Anne (2001). "Easter Island". In P.N. Peregine and M. Ember (eds.), Encyclopedia of Prehistory, Volume 3: East Asia and Oceania. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. ISBN 0-306-46257-5

- Van Tilburg, Jo Anne (2006). Remote Possibilities: Hoa Hakananai'a and HMS Topaze on Rapa Nui. British Museum Research Papers.

External links

- Moai statues at Easter Island Travel

- Moai database at Terevaka Archaeological Outreach