Fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish, which are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment (freshwater or marine), but may also be caught from stocked bodies of water such as ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. Fishing techniques include trawling, longlining, jigging, hand-gathering, spearing, netting, angling, shooting and trapping, as well as more destructive and often illegal techniques such as electrocution, blasting and poisoning.

The term fishing broadly includes catching aquatic animals other than fish, such as crustaceans (shrimp/lobsters/crabs), shellfish, cephalopods (octopus/squid) and echinoderms (starfish/sea urchins). The term is not normally applied to harvesting fish raised in controlled cultivations (fish farming). Nor is it normally applied to hunting aquatic mammals, where terms like whaling and sealing are used instead.

Fishing has been an important part of human culture since hunter-gatherer times. It is one of the few food production activities that has persisted from prehistory into the modern age, surviving both the Neolithic Revolution and successive Industrial Revolutions. In addition to fishing for food, people commonly fish as a recreational pastime. Fishing tournaments are held, and caught fish are sometimes kept long-term as preserved or living trophies. When bioblitzes occur, fish are typically caught, identified, and then released.

According to the United Nations FAO statistics, the total number of commercial fishers and fish farmers is estimated to be 39.0 million.[1] Fishing industries and aquaculture provide direct and indirect employment to over 500 million people in developing countries.[2] In 2005, the worldwide per capita consumption of fish captured from wild fisheries was 14.4 kilograms (32 lb), with an additional 7.4 kilograms (16 lb) harvested from fish farms.[3]

History

Fishing is an ancient practice that dates back to at least the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic period about 40,000 years ago.[4] Isotopic analysis of the remains of Tianyuan man, a 40,000-year-old modern human from eastern Asia, has shown that he regularly consumed freshwater fish.[5][6] Archaeology features such as shell middens,[7] discarded fish bones, and cave paintings show that seafood was important for survival and consumed in significant quantities. Fishing in Africa is evident very early on in human history. Neanderthals were fishing by about 200,000 BC.[8] People could have developed basketry for fish traps, using spinning and early forms of knitting to make fishing nets[8] able to catch more fish.[9]

During this period, most people lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle and were, of necessity, constantly on the move. However, where there are early examples of permanent settlements (though not necessarily permanently occupied) such as those at Lepenski Vir, they are almost always associated with fishing as a major source of food.

Trawling

The British dogger was a very early type of sailing trawler from the 17th century, but the modern fishing trawler was developed in the 19th century, at the English fishing port of Brixham. By the early 19th century, the fishers at Brixham needed to expand their fishing area further than ever before due to the ongoing depletion of stocks that was occurring in the overfished waters of South Devon. The Brixham trawler that evolved there was of a sleek build and had a tall gaff rig, which gave the vessel sufficient speed to make long-distance trips out to the fishing grounds in the ocean. They were also sufficiently robust to be able to tow large trawls in deep water. The great trawling fleet that built up at Brixham earned the village the title of 'Mother of Deep-Sea Fisheries'.[10]

This revolutionary design made large-scale trawling in the ocean possible for the first time, resulting in a massive migration of fishers from the ports in the south of England, to villages further north, such as Scarborough, Hull, Grimsby, Harwich and Yarmouth, that were points of access to the large fishing grounds in the Atlantic Ocean.[10]

The small village of Grimsby grew to become the largest fishing port in the world[11] by the mid 19th century. An Act of Parliament was first obtained in 1796, which authorised the construction of new quays and dredging of the Haven to make it deeper.[12] It was only in 1846, with the tremendous expansion in the fishing industry, that the Grimsby Dock Company was formed. The foundation stone for the Royal Dock was laid by Albert the Prince consort in 1849. The dock covered 25 acres (10 ha) and was formally opened by Queen Victoria in 1854 as the first modern fishing port.

The elegant Brixham trawler spread across the world, influencing fishing fleets everywhere.[13] By the end of the 19th century, there were over 3,000 fishing trawlers in commission in Britain, with almost 1,000 at Grimsby. These trawlers were sold to fishers around Europe, including from the Netherlands and Scandinavia. Twelve trawlers went on to form the nucleus of the German fishing fleet.[14]

The earliest steam-powered fishing boats first appeared in the 1870s and used the trawl system of fishing as well as lines and drift nets. These were large boats, usually 80–90 feet (24–27 m) in length with a beam of around 20 feet (6 m). They weighed 40–50 tons and travelled at 9–11 knots (17–20 km/h; 10–13 mph). David Allen designed and made the earliest purpose-built fishing vessels in Leith, Scotland in March 1875, when he converted a drifter to steam power. In 1877, he built the first screw propelled steam trawler in the world.[15]

Steam trawlers were introduced at Grimsby and Hull in the 1880s. In 1890 it was estimated that there were 20,000 men on the North Sea. The steam drifter was not used in the herring fishery until 1897. The last sailing fishing trawler was built in 1925 in Grimsby. Trawler designs adapted as the way they were powered changed from sail to coal-fired steam by World War I to diesel and turbines by the end of World War II.

In 1931, the first powered drum was created by Laurie Jarelainen. The drum was a circular device that was set to the side of the boat and would draw in the nets. Since World War II, radio navigation aids and fish finders have been widely used. The first trawlers fished over the side, rather than over the stern. The first purpose-built stern trawler was Fairtry built in 1953 at Aberdeen, Scotland. The ship was much larger than any other trawlers then in operation and inaugurated the era of the 'super trawler'. As the ship pulled its nets over the stern, it could lift out a much greater haul of up to 60 tons.[16] The ship served as a basis for the expansion of 'super trawlers' around the world in the following decades.[16]

Recreational fishing

Woodcut by Louis Rhead

The early evolution of fishing as recreation is not clear. For example, there is anecdotal evidence for fly fishing in Japan. However, fly fishing was likely to have been a means of survival, rather than recreation. The earliest English essay on recreational fishing was published in 1496, by Dame Juliana Berners, the prioress of the Benedictine Sopwell Nunnery. The essay was titled Treatyse of Fysshynge wyth an Angle,[17] and included detailed information on fishing waters, the construction of rods and lines, and the use of natural baits and artificial flies.[18]

Recreational fishing took a great leap forward after the English Civil War, where a newly found interest in the activity left its mark on the many books and treatises that were written on the subject at the time. Leonard Mascall in 1589 wrote A booke of Fishing with Hooke and Line along with many others he produced in his life on game and wildlife in England at the time. The Compleat Angler was written by Izaak Walton in 1653 (although Walton continued to add to it for a quarter of a century) and described the fishing in the Derbyshire Wye. It was a celebration of the art and spirit of fishing in prose and verse. A second part to the book was added by Walton's friend Charles Cotton.[19]

Charles Kirby designed an improved fishing hook in 1655 that remains relatively unchanged to this day. He went on to invent the Kirby bend, a distinctive hook with an offset point, still commonly used today.[20]

The 18th century was mainly an era of consolidation of the techniques developed in the previous century. Running rings began to appear along the fishing rods, which gave anglers greater control over the cast line. The rods themselves were also becoming increasingly sophisticated and specialised for different roles. Jointed rods became common from the middle of the century and bamboo came to be used for the top section of the rod, giving it much greater strength and flexibility.

The industry also became commercialised – rods and tackle were sold at the haberdashers store. After the Great Fire of London in 1666, artisans moved to Redditch which became a centre of production of fishing-related products from the 1730s. Onesimus Ustonson established his shop in 1761, and his establishment remained a market leader for the next century. He received a royal warrant from three successive monarchs starting with King George IV.[21] He also invented the multiplying winch. The commercialization of the industry came at a time of expanded interest in fishing as a recreational hobby for members of the aristocracy.[22]

The impact of the Industrial Revolution was first felt in the manufacture of fly lines. Instead of anglers twisting their lines – a laborious and time-consuming process – the new textile spinning machines allowed for a variety of tapered lines to be easily manufactured and marketed.

British fly fishing continued to develop in the 19th century, with the emergence of fly fishing clubs, along with the appearance of several books on the subject of fly tying and fly fishing techniques.

By the mid to late 19th century, expanding leisure opportunities for the middle and lower classes began to have an effect on fly fishing, which steadily grew in mass appeal. The expansion of the railway network in Britain allowed the less affluent for the first time to take weekend trips to the seaside or rivers for fishing. Richer hobbyists ventured further abroad.[23] The large rivers of Norway replete with large stocks of salmon began to attract fishers from England in large numbers in the middle of the century – Jones's guide to Norway, and salmon-fisher's pocket companion, published in 1848, was written by Frederic Tolfrey and was a popular guide to the country.[23]

Modern reel design had begun in England during the latter part of the 18th century, and the predominant model in use was known as the 'Nottingham reel'. The reel was a wide drum that spooled out freely and was ideal for allowing the bait to drift a long way out with the current. Geared multiplying reels never successfully caught on in Britain, but had more success in the United States, where George Snyder of Kentucky modified similar models into his bait-casting reel, the first American-made design in 1810.[24]

The material used for the rod itself changed from the heavy woods native to England to lighter and more elastic varieties imported from abroad, especially from South America and the West Indies. Bamboo rods became the generally favoured option from the mid-19th century, and several strips of the material were cut from the cane, milled into shape, and then glued together to form the light, strong, hexagonal rods with a solid core that were superior to anything that preceded them. George Cotton and his predecessors fished their flies with long rods, and light lines allowing the wind to do most of the work of getting the fly to the fish.[25]

Tackle design began to improve in the 1880s. The introduction of new woods to the manufacture of fly rods made it possible to cast flies into the wind on silk lines, instead of horse hair. These lines allowed for a much greater casting distance. However, these early fly lines proved troublesome as they had to be coated with various dressings to make them float and needed to be taken off the reel and dried every four hours or so to prevent them from becoming waterlogged. Another negative consequence was that it became easy for the much longer line to get into a tangle – this was called a 'tangle' in Britain, and a 'backlash' in the US. This problem spurred the invention of the regulator to evenly spool the line out and prevent tangling.[25]

The American, Charles F. Orvis, designed and distributed a novel reel and fly design in 1874, described by reel historian Jim Brown as the "benchmark of American reel design," and the first fully modern fly reel.[26][27]

Albert Illingworth, 1st Baron Illingworth a textiles magnate, patented the modern form of fixed-spool spinning reel in 1905. When casting Illingworth's reel design, the line was drawn off the leading edge of the spool but was restrained and rewound by a line pickup, a device which orbits around the stationary spool. Because the line did not have to pull against a rotating spool, much lighter lures could be cast than with conventional reels.[25]

The development of inexpensive fiberglass rods, synthetic fly lines, and monofilament leaders in the early 1950s revived the popularity of fly fishing.

Techniques

There are many fishing techniques and tactics for catching fish. The term can also be applied to methods for catching other aquatic animals such as molluscs (shellfish, squid, octopus) and edible marine invertebrates.

Fishing techniques include hand gathering, spearfishing, netting, angling, bowfishing and trapping, as well as less common techniques such as gaffing, snagging, clubbing and the use of specially trained animals such as cormorants and otters. There are also destructive fishing techniques (such as electrocution, blasting and poisoning) that can do irreversible damage to the local ecosystems by killing/sterilizing entire fish stocks, habitat destruction and/or upsetting the equilibrium of interspecific competitions, and such practices are often deemed illegal and liable to criminal punishments.

Recreational, commercial and artisanal fishers use different techniques, and also, sometimes, the same techniques. Recreational fishers fish for pleasure, sport, or to provide food for themselves, while commercial fishers fish for profit. Artisanal fishers use traditional, low-tech methods, for survival in third-world countries, and as a cultural heritage in other countries. Usually, recreational fishers use angling methods and commercial fishers use netting methods. A modern development is to fish with the assistance of a drone.[28]

Why a fish bites a baited hook or lure involves several factors related to the sensory physiology, behaviour, feeding ecology, and biology of the fish as well as the environment and characteristics of the bait/hook/lure.[29] There is an intricate link between various fishing techniques and knowledge about the fish and their behaviour including migration, foraging and habitat. The effective use of fishing techniques often depends on this additional knowledge.[30] Some fishers follow fishing folklores which claim that fish feeding patterns are influenced by the position of the sun and the moon.

Tackle

Fishing tackles are the equipment used by fishers when fishing. Almost any equipment or gear used for fishing can be called a fishing tackle, although the term is most commonly associated with gear used in angling. Some examples are hooks, lines, sinkers, floats, rods, reels, baits, lures, spears, nets, gaffs, traps, waders, and tackle boxes. Fishing techniques refer to the ways the tackles are used when fishing.

Tackles that are attached to the end of a fishing line are collectively called terminal tackles. These include hooks, sinkers, floats, leader lines, swivels, split rings, and any wires, snaps, beads, spoons, blades, spinners and clevises used to attach spinner blades to fishing lures. People also tend to use dead or live bait fish as another form of bait.

Fishing vessels

A fishing vessel is a boat or ship used to catch fish in the sea, or on a lake or river. Many different kinds of vessels are used in commercial, artisanal, and recreational fishing.

According to the FAO, in 2004 there were four million commercial fishing vessels.[31] About 1.3 million of these are decked vessels with enclosed areas. Nearly all of these decked vessels are mechanised, and 40,000 of them are over 100 tons. At the other extreme, two-thirds (1.8 million) of the undecked boats are traditional craft of various types, powered only by sail and oars.[31] These boats are used by artisan fishers.

It is difficult to estimate how many recreational fishing boats there are, although the number is high. The term is fluid since some recreational boats may also be used for fishing from time to time. Unlike most commercial fishing vessels, recreational fishing boats are often not dedicated just to fishing. Just about anything that will stay afloat can be called a recreational fishing boat, so long as a fisher periodically climbs aboard with the intent to catch a fish. Fish are caught for recreational purposes from boats which range from dugout canoes, float tubes, kayaks, rafts, stand up paddleboards, pontoon boats and small dinghies to runabouts, cabin cruisers and cruising yachts to large, hi-tech and luxurious big game rigs.[32] Larger boats, purpose-built with recreational fishing in mind, usually have large, open cockpits at the stern, designed for convenient fishing.

Traditional fishing

Traditional fishing is any kind of small scale, commercial or subsistence fishing practices using traditional techniques such as rod and tackle, arrows and harpoons, throw nets and drag nets, etc.

Recreational fishing

Recreational and sport fishing refer to fishing primarily for pleasure or competition. Recreational fishing has conventions, rules, licensing restrictions and laws that limit how fish may be caught; typically, these prohibit the use of nets and the catching of fish with hooks not in the mouth. The most common form of recreational fishing is done with a rod, reel, line, hooks and any one of a wide range of baits or lures such as artificial flies. The practice of catching or attempting to catch fish with a hook is generally known as angling. In angling, it is sometimes expected or required that fish be returned to the water (catch and release). Recreational or sport fishermen may log their catches or participate in fishing competitions.

The estimated global number of recreational fishers varies from 220 million to a maximum number of 700 million fishers globally,[33] which is thought to be double the number of individuals working as commercial fishers. In the United States alone it was estimated that 50.1 million people engaged in fishing activities in both saltwater and freshwater environments.[34]

Big-game fishing is fishing from boats to catch large open-water species such as swordfish, tuna, sharks, and marlin. Sportfishing (sometimes game fishing) is recreational fishing where the primary reward is the challenge of finding and catching the fish rather than the culinary or financial value of the fish's flesh. Fish sought after include tarpon, sailfish, mackerel, grouper and many others.

Fishing industry

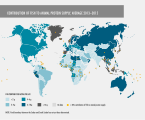

- Contribution of fish to animal protein supply, average 2013–2015

- World capture fisheries and aquaculture production 1950 - 2015

- A comparison of employment In agriculture, forestry and fishing by region

The fishing industry includes any industry or activity concerned with taking, culturing, processing, preserving, storing, transporting, marketing or selling fish or fish products. It is defined by the FAO as including recreational, subsistence and commercial fishing, and the harvesting, processing, and marketing sectors.[35] The commercial activity is aimed at the delivery of fish and other seafood products for human consumption or use as raw material in other industrial processes. In 2022 24% of fishers and fish farmers and 62% of workers in post-harvest sector were women.[36]

There are three principal industry sectors:[note 1]

- The commercial sector comprises enterprises and individuals associated with wild-catch or aquaculture resources and the various transformations of those resources into products for sale.

- The traditional sector comprises enterprises and individuals associated with fisheries resources from which aboriginal people derive products following their traditions.

- The recreational sector comprises enterprises and individuals associated with the purpose of recreation, sport or sustenance with fisheries resources from which products are derived that are not for sale.

Commercial fishing

Commercial fishing is the capture of fish for commercial purposes. Those who practice it must often pursue fish far from the land under adverse conditions. Commercial fishermen harvest a wide range of aquatic species, from tuna, cod and salmon to shrimp, krill, lobster, clams, squid and crab, in various fisheries for these species. Commercial fishing methods have become very efficient using large nets and sea-going processing factories. Individual fishing quotas and international treaties seek to control the species and quantities caught.

A commercial fishing enterprise may vary from one person with a small boat with hand-casting nets or a few pot traps, to a huge fleet of trawlers processing tons of fish every day.

Commercial fishing gear includes weights, nets (e.g. purse seine), seine nets (e.g. beach seine), trawls (e.g. bottom trawl), dredges, hooks and line (e.g. long line and handline), lift nets, gillnets, entangling nets and traps.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the total world capture fisheries production in 2000 was 86 million tons (FAO 2002). The top producing countries were, in order, the People's Republic of China (excluding Hong Kong and Taiwan), Peru, Japan, the United States, Chile, Indonesia, Russia, India, Thailand, Norway, and Iceland. Those countries accounted for more than half of the world's production; China alone accounted for a third of the world's production. Of that production, over 90% was marine and less than 10% was inland.

A small number of species support the majority of the world's fisheries. Some of these species are herring, cod, sardine, anchovy, tuna, flounder, mullet, squid, shrimp, salmon, crab, lobster, oyster and scallops. All except these last four provided a worldwide catch of well over a million tonnes in 1999, with herring and sardines together providing a catch of over 22 million metric tons in 1999. Many other species as well are fished in smaller numbers.

Fish farms

Fish farming is the principal form of aquaculture, while other methods may fall under mariculture. It involves raising fish commercially in tanks or enclosures, usually for food. A facility that releases juvenile fish into the wild for recreational fishing or to supplement a species' natural population is generally referred to as a fish hatchery. Fish species raised by fish farms include salmon, carp, tilapia, catfish, white seabass and trout.

Increased demands on wild fisheries by commercial fishing has caused widespread overfishing. Fish farming offers an alternative solution to the increasing market demand for fish.

Fish products

Fish and fish products are consumed as food all over the world. With other seafoods, it provides the world's prime source of high-quality protein: 14–16 percent of the animal protein consumed worldwide. Over one billion people rely on fish as their primary source of animal protein.[38]

Fish and other aquatic organisms are also processed into various food and non-food products, such as sharkskin leather, pigments made from the inky secretions of cuttlefish, isinglass used for the clarification of wine and beer, fish emulsion used as a fertiliser, fish glue, fish oil and fish meal.

Fish are also collected live for research and the aquarium trade.

Fish marketing

Fisheries management

Fisheries management draws on fisheries science to find ways to protect fishery resources so sustainable exploitation is possible. Modern fisheries management is often referred to as a governmental system of management rules based on defined objectives and a mix of management means to implement the rules, which are put in place by a system of monitoring control and surveillance.

Fisheries science is the academic discipline of managing and understanding fisheries. It is a multidisciplinary science, which draws on the disciplines of oceanography, marine biology, marine conservation, ecology, population dynamics, economics and management in an attempt to provide an integrated picture of fisheries. In some cases new disciplines have emerged, such as bioeconomics.

Sustainability

Stocks fished within biologically sustainable levels decreased from 90% in 1974 to 62.3% in 2021.[39] Issues involved in the long term sustainability of fishing include overfishing, by-catch, marine pollution, environmental effects of fishing, ghost fishing, climate change, fisheries-induced evolution and fish farming.

Conservation issues are part of marine conservation, and are addressed in fisheries science programs. There is a growing gap between how many fish are available to be caught and humanity's desire to catch them, a problem that gets worse as the world population grows.

Similar to other environmental issues, there can be conflict between the fishermen who depend on fishing for their livelihoods and fishery scientists who realise that if future fish populations are to be sustainable then some fisheries must limit fishing or cease operations.

Animal welfare concerns

Historically, some doubted that fish could experience pain. Laboratory experiments have shown that fish do react to painful stimuli (e.g., injections of bee venom) in a similar way to mammals.[40][41] This is controversial and has been disputed.[further explanation needed][42] The expansion of fish farming as well as animal welfare concerns in society has led to research into more humane and faster ways of killing fish.[43]

In large-scale operations like fish farms, stunning fish with electricity or putting them into water saturated with nitrogen so that they cannot breathe, results in death more rapidly than just taking them out of the water. For sport fishing, it is recommended that fish be killed soon after catching them by hitting them on the head followed by bleeding out or by stabbing the brain with a sharp object[44] (called pithing or ike jime in Japanese). Some believe it is not cruel if you release the catch back to where it was caught however a study in 2018 states that the hook damages an important part of the feeding mechanism by which the fish sucks in food, ignoring the issue of pain.[45]

When fishing there are high chances of catching other marine wildlife in a fishing net. There are over 100 different fishing regulations on paper for reducing this bycatch.[46]

Plastic pollution

Abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear includes netting, mono/multifilament lines, hooks, ropes, floats, buoys, sinkers, anchors, metallic materials and fish aggregating devices (FADs) made of non-biodegradable materials such as concrete, metal and polymers. It has been estimated that global fishing gear losses each year include 5.7% of all fishing nets, 8.6% of all traps and 29% of all lines used. Abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) can have serious impacts on marine organisms through entanglement and ingestion.[47] The potential for fishing gear to become ALDFG depends on a number of factors including:

- Environmental factors are mostly related to seafloor topography and obstructions, although tides, currents, waves, winds, and interaction with wildlife are also important.

- Operational losses and operator errors can occur even during normal fishing operations.

- Problems such as inadequate fisheries management and regulations that do not include adequate controls can hamper collection of ALDFG (e.g. there may be poor access to collection facilities).

- Gear loss resulting from conflicts primarily occurs (intentionally or unintentionally) in areas with high concentrations of fishing activities, leading to gear being towed away, fouled, sabotaged or vandalized. Passive and unattended gear such as pots, set gillnets and traps are particularly prone to conflict damage. In the Arctic, conflicts are the most common reason for lost gear.[47]

Cultural impact

Community

For communities like fishing villages, fisheries provide not only a source of food and work but also a community and cultural identity.[48]

Economic

Some locations may be regarded as fishing destinations, which anglers visit on vacation or for competitions. The economic impact of fishing by visitors may be a significant, or even primary driver of tourism revenue for some destinations.

Semantic

A "fishing expedition" is a situation where an interviewer implies they know more than they do to trick their target into divulging more information than they wish to reveal. Other examples of fishing terms that carry a negative connotation are: "fishing for compliments", "to be fooled hook, line and sinker" (to be fooled beyond merely "taking the bait"), and the internet scam of phishing, in which a third party will duplicate a website where the user would put sensitive information (such as bank codes).

Religious

Fishing has had an effect on major religions,[49] including Christianity,[50][51] Hinduism, and the various new age[52] religions. Jesus was said to participate in fishing excursions, and a number of the miracles and many parables and stories reported in the Bible involve fish or fishing. Since the Apostle Peter[53] was a fisherman, the Catholic Church has adopted the use of the fishermans ring into the Pope's traditional vestments.

See also

Notes

References

- ^ FAO (2020). "The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020: Sustainability in Action". The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture. Rome: FAO: 7. doi:10.4060/ca9229en. hdl:10535/3776. ISBN 978-92-5-132692-3.

- ^ Fisheries and Aquaculture in our Changing Climate Archived 23 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine Policy brief of the FAO for the UNFCCC COP-15 in Copenhagen, December 2009.

- ^ "Fisheries and Aquaculture". FAO. Archived from the original on 13 May 2009. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ^ African Bone Tools Dispute Key Idea About Human Evolution National Geographic News article. (archived 17 January 2006)

- ^ Yaowu Hu, Y; Hong Shang, H; Haowen Tong, H; Olaf Nehlich, O; Wu Liu, W; Zhao, C; Yu, J; Wang, C; Trinkaus, E; Richards, M (2009). "Stable isotope dietary analysis of the Tianyuan 1 early modern human". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (27): 10971–74. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10610971H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0904826106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2706269. PMID 19581579.

- ^ First direct evidence of substantial fish consumption by early modern humans in China Archived 15 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine PhysOrg.com, 6 July 2009.

- ^ Coastal Shell Middens and Agricultural Origins in Atlantic Europe Archived 26 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b "History of fishing – fishing nets, shellfish, boats". quatr.us Study Guides. 12 June 2017. Archived from the original on 3 May 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Alfaro Giner, Carmen (2010). "Fishing nets in the ancient world: the historical and archaeological evidence". Ancient nets and fishing gear: Proceedings of the international workshop on Nets and fishing gear in classical antiquity: A first approach: Cádiz, November 15–17, 2007. - ( Monographs of the Sagena project; 2): 55–81.

- ^ a b "History of a Brixham trawler". JKappeal.org. 2 March 2009. Archived from the original on 2 December 2010. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ Days out: "Gone fishing in Grimsby"[permanent dead link] The Independent, 8 September 2002 [dead link]

- ^ "A brief history of Grimsby". localhistories.org. 14 March 2021. Archived from the original on 24 April 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ "Pilgrim's restoration under full sail". BBC. Archived from the original on 17 November 2002. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ^ Sailing trawlers. issuu. 10 January 2014. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ "The Steam Trawler". Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ a b "HISTORY". Archived from the original on 21 August 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ Berners, Dame Juliana (1496) A treatyse of fysshynge wyth an Angle Archived 29 June 2023 at the Wayback Machine (transcription by Risa S. Bear).

- ^ Berners, Dame Juliana. (2008). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 20 June 2008, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ^ Andrew N. Herd. "Fly fishing techniques in the fifteenth century". Archived from the original on 22 October 2021. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ Stan L. Ulanski (2003). The Science of Fly-fishing. University of Virginia Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-8139-2210-2.

- ^ "Welcome To Great Fly Fishing Tips". December 2011. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ "Fishing Tackle Chapter 3" (PDF). CLAM PRODUCTIONS. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ a b Andrew N. Herd. "Fly Fishing in the Years 1800–1850". Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ Andrew N. Herd. "Fly Fishing in the Eighteenth Century". Archived from the original on 19 July 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ a b c "fishing". Encyclopedia Britannica. July 2023. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Brown, Jim. A Treasury of Reels: The Fishing Reel Collection of The American Museum of Fly Fishing. Manchester, Vermont: The American Museum of Fly Fishing, 1990.

- ^ Schullery, Paul. The Orvis Story: 150 Years of an American Sporting Tradition. Manchester, Vermont, The Orvis Company, Inc., 2006

- ^ Fishing with a drone Archived 12 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine Stuff, 15 December 2015.

- ^ Lennox, Robert J; Alós, Josep; Arlinghaus, Robert; Horodysky, Andrij; Klefoth, Thomas; Monk, Christopher T; Cooke, Steven J (2017). "What makes fish vulnerable to capture by hooks? A conceptual framework and a review of key determinants". Fish and Fisheries. 18 (5): 986–1010. Bibcode:2017AqFF...18..986L. doi:10.1111/faf.12219. ISSN 1467-2979.

- ^ Keegan, William F (1986) New Series, Volume. 88, No. 1., pp. 92–107.

- ^ a b FAO 2007

- ^ NOAA: Sport fishing boat Archived 6 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ FAO. "The role of Recreational Fisheries in the sustainable management of marine resources | GLOBEFISH | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations". www.fao.org. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Lange, David. "Topic: Recreational Fishing in the U.S." Statista. Archived from the original on 9 February 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ FAO Fisheries Section: Glossary: Fishing industry. Archived 8 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- ^ The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024. FAO. 7 June 2024. doi:10.4060/cd0683en. ISBN 978-92-5-138763-4.

- ^ "Today's Fishing Industry". Fisheries Research and Development Corporation. 10 December 2007. Archived from the original on 14 June 2009. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Tidwell, James H. and Allan, Geoff L.

- ^ The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024. FAO. 7 June 2024. doi:10.4060/cd0683en. ISBN 978-92-5-138763-4.

- ^ Sneddon, LU (2009). "Pain perception in fish: indicators and endpoints". ILAR Journal. 50 (4): 38–42. doi:10.1093/ilar.50.4.338. PMID 19949250. Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ Oidtmann, B; Hoffman, RW (July–August 2001). "Pain and suffering in fish". Berliner und Münchener Tierärztliche Wochenschrift. 114 (7–8): 277–282. PMID 11505801.

- ^ "Do fish feel pain? Not as humans do, study suggests". ScienceDaily. 8 August 2013. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ Lund, V; Mejdell, CM; Röcklinsberg, H; Anthony, R; Håstein, T (4 May 2007). "Expanding the moral circle: farmed fish as objects of moral concern". Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 75 (2): 109–118. doi:10.3354/dao075109. PMID 17578250.

- ^ Davie, PS; Kopf, RK (August 2006). "Physiology, behaviour and welfare of fish during recreational fishing and after release". New Zealand Veterinary Journal. 54 (4): 161–172. doi:10.1080/00480169.2006.36690. PMID 16915337. S2CID 1636511.

- ^ "Anglers' catch-and-release method stops fish feeding properly, study finds". The Independent. 9 October 2018. Archived from the original on 9 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "Facts | Seaspiracy Website". SEASPIRACY. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ a b Environment, U. N. (21 October 2021). "Drowning in Plastics – Marine Litter and Plastic Waste Vital Graphics". UNEP - UN Environment Programme. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "International Collective in Support of Fishworkers". ICSF. 2 March 2012. Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ^ Regensteinn J.M. and Regensteinn C.E. (2000) "Religious food laws and the seafood industry" Archived 4 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine In: R.E. Martin, E.P. Carter, G.J. Flick Jr and L.M. Davis (Eds) (2000) Marine and freshwater products handbook, CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-56676-889-4.

- ^ A Misunderstood Analogy for Evangelism Archived 20 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Bible Analysis Article

- ^ American Bible Society Article Archived 5 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine American Bible Society

- ^ About Pisces the Fish Archived 6 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine The Astrology Cafe Monitor

- ^ Peter: From Fisherman to Fisher of Men Profiles of Faith Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under Cc BY-SA 3.0 IGO (license statement/permission). Text taken from Drowning in Plastics – Marine Litter and Plastic Waste Vital Graphics, United Nations Environment Programme.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under Cc BY-SA 3.0 IGO (license statement/permission). Text taken from Drowning in Plastics – Marine Litter and Plastic Waste Vital Graphics, United Nations Environment Programme.

Further reading

- Schultz, Ken (1999). Fishing Encyclopedia: Worldwide Angling Guide. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-02-862057-2.

- Gabriel, Otto; Andres von Brandt (2005). Fish catching methods of the world. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-85238-280-6.

- Sahrhage, Dietrich; Johannes Lundbeck (1992). A History of Fishing. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-55332-0.

External links

- "The sea without fish, a reality!". Pauly, Daniel (2009). University of British Columbia. Archived from the original on 7 January 2013..

- Map of world ocean fishing activity, 2016