Zurich Bible of 1531

The Zurich Bible of 1531, also known as the Froschauer Bible of 1531, is a translation of the Bible from the Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek language into German, which was printed in 1531 in the Dispensaryof Christoph Froschauer in Zurich. The entire New Testament and large parts of the Old Testament are an adaptation of Martin Luther's translation. The biblical prophetic books were translated by the circle around Huldrych Zwingli independently of the Luther Bible, but using the Worms Prophets. The new translation of the poetic books, including the Psalms, is an independent work by the Zurich scholars.

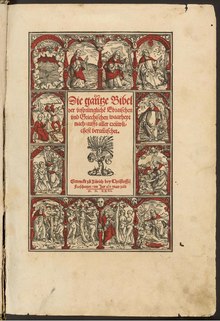

The two-volume splendid edition in Folio bears the title: Die gantze Bibel der vrsprünglichē Ebraischen und Griechischen waarheyt nach/ auffs aller treüwlichest verteütschet. It is richly illustrated, partly with woodcuts after drawings by Hans Holbein the Younger. A preface, probably written by Leo Jud, shows strong influence from Erasmus of Rotterdam. Elaborate additions such as a keyword index, summaries (chapter summaries), glosses and parallel passages make the text accessible.

Language of the Zurich Bible

The language of the Zurich Bible cannot be equated with the language of Zwingli. Unlike Luther, the Zurich reformer was more effective through his sermons than through his printed writings. He always preached freely and was very popular. According to Heinrich Bullinger, Zwingli spoke in the simple tone of the people: "er redt gar Landtlich".[1][2] Walter Schenker concludes from this that it was more important to Zwingli "to reach as many social classes as possible in his region with his language than to be understood in as many German regions as possible".[3]

The first New Testaments printed by Froschauer in Zurich were adaptations of Basel reprints of Luther's translation and featured the Old Swiss Middle High German vocalism; they retained the old long vowels ī/ȳ, ū and ǖ, which corresponded to the Office language common in the Confederation at the time.[4] They thus differed significantly from the Luther Bible with its New High German Diphthongization (ei/ey, au, äu/eu). However, Froschauer adopted this New High German diphthongization for the Zurich Bibles from 1527 onwards. It is possible that he wanted to reach beyond the Alemannic area to appeal to a larger clientele in central Germany.[5] The New High German Monophthongization, however, was not adopted in the Zurich Bible. The Zurich Bible therefore reads ie, ů, ue, where the Luther Bible has ī, ū, ü/u. An example (Acts 2:37 ZB):

- Luther 1522: yhr menner lieben bruder/ was sollen wyr thun?

- Zürich 1531: Ir menner lieben brueder/ was soellend wir thůn?

Wherever the translators of the Zurich Bible used the Luther Bible as a model, they also largely adopted its syntax. Werner Besch characterizes the Luther Bible as a read-aloud book: "Smaller statement units in a step-by-step sequence, ensuring understanding in an additive way, because a listener cannot turn back the pages like a reader."[6] In the biblical books, where the Zurichers were independent of the Luther Bible, they preferred the hypotactic style with the finite verb in the final position.[7]

In its system of forms and vocabulary, the Zurich Bible shows its "Alemannic independence" compared to the Luther Bible.[8]

In the inflection of the verb, Froschauer's Bibles, as in the Swiss chancery language[9] Indicative plural and subjunctive plural are distinguished:[10]

- Indicative: wir / yr / sy machend.

- Subjunctive: wir / yr / sy machind.

An example of this subjunctive (Mk 15,32 ZB):

- Luther 1522: Er steyge nu von dem creutze/ das wyr sehen vnd glewben.

- Zürich 1531: Er steyge nun von dem creütz/ das wir sehind vnd glaubind.

The Zurich translators often exchanged lexical expressions from the Luther Bible that seemed foreign; one example (Rom 9:21 ZB):[11]

- Luther 1522: Hat nicht eyn topffer macht/ auß eynem klumpen zumachen eyn faß?

- Zürich 1531: Hat nicht ein hafner macht/ auß einem leimklotzen zemachen ein geschirr?

According to Walter Schenker's analysis, almost half of these lexemes used by the Zurich translators in the Luther text are only regionally comprehensible. By opening up the East Central German to Bavarian, the Luther Bible strives for supra-regional comprehensibility, whereas the Zurich Bible does not.[12] According to Walter Haas, however, it was less a question of making an incomprehensible Luther text comprehensible at all than of "taking away some of its foreignness and thus increasing its acceptance".[13]

Collective work or "Zwingli Bible"?

The Wittenberg translation of the Bible is known as the "Luther Bible". It was completed in 1534, three years after the Zurich Bible. The term "Luther Bible" ignores how much Philipp Melanchthon contributed to it with his knowledge of Greek and Hebrew. However, Melanchthon and the other members of the Wittenberg translation team worked with Luther, who was, however, entitled to decide on all disputed points. In this respect, the Biblia Deudsch is indeed Luther's Bible.[14]

Zwingli did not claim to dominate the translation work in the same way as Luther. The focus was on collegiality. The Bible produced in Zurich was therefore not known as the "Zwingli Bible", but as the Zurich Bible or (after the printer) the Froschauer Bible. Researchers dispute the extent of Zwingli's contribution to this collaborative work.

Zurich "Prophecy"

Following the example of the Collegium trilingue, which Erasmus had founded in Leuven, Zwingli had been planning an institution for the study of biblical languages since 1523. The canons' monastery at Grossmünster was not to be dissolved like the Fraumünster Abbey, but transformed into an educational institution. This took up its teaching activities on June 19, 1525. As Zwingli described the interpretation of the Bible as "prophecy" with reference to 1 Cor 14:29 ZB, the institution was given the name Prophezey.[15] Initially in the Chor of the Grossmünster, later in St. Michael's Chapel and in winter in the Chorherrenstube, public Bible lessons were held daily (except Fridays and Sundays).

Wilfried Kettler emphasizes that the Zurich Bible of 1531 was a "joint work of the Prophezei", a "fruit" of the ongoing editing of the biblical books in this institution. He recognizes the work processes of the Prophezei in Zwingli's exegetical writings: first the translation of a Hebrew formulation into Latin, then a look at the Septuagint, and finally the theological discussion about it.[16] Accordingly, all eight teachers who belonged to this circle for a long or short time were involved in the Zurich Bible of 1531 - apart from Zwingli and Jud, the early deceased Hebraist Jakob Ceporin, Konrad Pellikan, Kaspar Megander, Johann Jakob Ammann, Rudolf Collin and Oswald Myconius. It is only possible to attribute certain biblical writings to one of these persons in the case of the Apocrypha, which Leo Jud translated alone.[17] Walter Schenker assumes that Zwingli gave "the general instructions" for the production of the Zurich Bible and that the exegetical implementation was a joint effort by the prophets and the printer for the regional lexeme alternatives to the Luther Bible.[18]

Zwingli as a translator

Traudel Himmighöfer estimates Zwingli's personal contribution to the Zurich Bible of 1531 to be very high. Zwingli owed much to the joint exegetical work in the Prophezei. However, he was "himself the translator and glossator of the first Zurich partial editions"; his translation decisions, based partly on philology and partly on theology, "remained decisive until the last Bible edition produced during his lifetime".[19] As he was ultimately responsible for the design of the work, the name "Zwingli Bible" was also justifiable.[20]

Himmighöfer points out that translation decisions and glosses correspond to Zwingli's exegetical writings. The books that Zwingli is known to have owned and used are also the working tools that were used for the Zurich Bibles up to 1531: above all the Novum Testamentum omne by Erasmus with its Latin translation and annotations (Annotationes), the Septuagint and Johannes Reuchlin's introduction to Hebrew (De rudimentis hebraicis).[19]

Zwingli's Hebrew Bible has not survived. As he refers to a printing error in Jer 39:12 in a note in his Latin commentary on Jeremiah, he must have owned a copy of the second edition of the Rabbinerbibel in Quart.[21] Reuchlin's De rudimentis hebraicis was apparently Zwingli's only textbook and dictionary for working on the Hebrew text. When he got stuck with it, he preferred to use the ancient Greek translation of the Septuaginta, and only exceptionally the Latin Vulgata.[22]

Zwingli owned a complete Greek Bible (Sacrae Scripturae veteris novaeque omnia), which had been printed in 1518 by Aldus Manutius in Venice and which he worked through intensively. He quoted from it at the Marburg Religious Conference in 1529.[23] The Reformer was particularly interested in demonstrating the inner connection between the Old and New Testaments. He liked to explain the meaning of New Testament Greek terms by using the language of the Septuagint, flipping back and forth, so to speak, between the front and back parts of his complete Greek Bible.

An example of the use of the Novum Testamentum omne is the use of the Comma Johanneum (1 John 5:7-8 ZB). Erasmus omitted this traditional evidence for the doctrine of the Trinity in his first two editions of the Greek New Testament, as it was missing from the Greek manuscripts. Criticized as an Arian, he was then forced to include it in the third edition in 1522. In the Zurich Bible of 1531, the Comma Johanneum is included, but in small print and in a formulation that takes up Erasmus' explanation in the Annotationes: the three serve as one. Zwingli evidently liked the fact that Erasmus emphasized the functional unity of the Trinity (going beyond the Greek text); in his commentary on 1 John, he quoted Erasmus verbatim at this point.[24]

According to the Zurich Bible 1531, the apostle Paul was married, because in Brief an die Philipper (Phil 4:3 ZB), he addresses his wife: "Yes, I also ask you, my eighteenth and eternal husband ... The Greek text allows this interpretation, but the Latin translation of the Vulgate does not, and Luther adhered to the Vulgate in this passage. However, Erasmus had pointed out in the Annotationes that various Greek theologians believed that Paul was married. Zwingli agreed with Erasmus in his interpretation of Philippians.[25]

Different approaches to the Communion in Wittenberg and Zurich are reflected in the respective Bible translations. In the September Testament of 1522, Luther referred to the cup used in the Christian celebration of the Lord's Supper (1 Cor 10:16 ZB) as the kilch der benedeyung (= blessing), while the Zurich Bible of 1531 called it the kelch der dancksagung.[26] In accordance with the principle that Christ had only sacrificed himself and that no (Measurement) victims was necessary since then, Zwingli took action against Luther's frequent use of the verb "sacrifice" in the New Testament and replaced it where possible. According to Himmighöfer, he endeavored to "carry the Reformation into the use of language and to further advance it through his particular use of language".[27]

A peculiarity of the Zurich Bible is the rendering of a word in the source language by an "accumulation of related words and explanatory paraphrases" in the target language, which often reveals the meaning of the text.[28] Walter Schenker also finds these double and multiple translations in Bible quotations in Zwingli's sermons and writings. They are characteristic of the Zurich reformer and the boundary between translation and commentary is fluid in his work. He sees this as a deviation from Luther's efforts to reach the common man as a reader of the Bible translation. According to the Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen, Luther wanted to imitate the speech of the common man and thus be catchy. Zwingli wanted to "convey the Bible text to the reader as accurately as possible, whereby he could also abandon the German for the sake of didactics".[29] Walter Haas points out that doubling was a popular rhetorical device, especially in legal texts. What seems cumbersome to today's readers was stylistically impressive in the 16th century.[30]

Nevertheless, Wilfried Kettler states that the original Hebrew or Greek meaning of the words in the Zurich Bible of 1531 was often not correctly recorded. However, this was not a deliberately biased translation, but rather a struggle on the part of the translators with Hebrew-Aramaic or Greek text editions, which were inadequate compared to today's scholarly text editions. Sentences had often been so distorted in the course of transmission that they were actually untranslatable.[31] Based on the text passages he compared in the Zurich Bible and the Luther Bible, Kettler judges that both endeavored to capture the original text and render it in the vernacular. In the Psalms, for example, sometimes Luther and sometimes the Zurich Bible capture the Hebrew meaning better. It is therefore impossible to judge which translation is more accurate overall than the other.[32] Himmighöfer's judgment is also ambivalent: The biblical philological approach of the Zurich translators had in part achieved greater accuracy compared to the Luther text, but had also often turned into the opposite in that paraphrases, additions and commentaries were incorporated into the translated text, which thus moved away from the original text.[33]

Preliminary stages of the Zurich Bible of 1531

Luther's translation is the template for the Zurich Bible for all books of the New Testament. In the Old Testament, Luther's Bible was used for the Pentateuch and the books of history (i.e. from Genesis to Book of Esther). In contrast, the Zurich team of translators worked independently of Luther on the linguistically most difficult books of the Hebrew Bible, the books of the prophets and the poetic writings, including the Book of Psalms.[34]

Adaptations of the Luther translation

Luther's translation of the Greek New Testament into Early New High German was printed by Melchior Lotter in Wittenberg in 1522 (September Testament). Its 3000 copies were quickly sold. Throughout the German-speaking world, the reprinting of Luther's New Testament and the parts of the Old Testament that then appeared in deliveries was very attractive financially; it was also these reprints, rather than the products of the Wittenberg printers, that made Luther's translation widely known. Reprinting did not simply mean copying the Wittenberg text, but "adapting" it to the regional language of the place of printing.[35]

Even before Lotter had printed the corrected second edition (December Testament) at the end of 1522, his Basel competitor Adam Petri had brought a reprint onto the market under the title Das new Testament yetzund recht grüntlich teutscht. Like Lotter, Petri did not state who the translator was. However, this was known. The librarian of the St. Margarethental Monastery in Kleinbasel noted in Petri's New Testament: It was made as one respects by M. Luthero [...] wiewol sin nam niená verzeichnet ist.[36] Petri's Basel reprint was a careful "adaptation" of Luther's text into the linguistic form of the Basel region.[37] It was also widely bought and read in Zurich. At the First Zurich Disputation at the beginning of 1523, Zwingli spoke very positively about this German-language New Testament. He called on the pastors: ... kouff ein yeder ein nüw testament in latin oder in tütsch, wo er das latin nitt recht verstuend ...[38]

Around the turn of the year 1523/1524, the decision seems to have been made in Zurich to print Bible texts itself and to become independent of editions from other printing houses. The target group was the Reformed pastors as multipliers, but also the pupils and the literate population in general. The initiative for this seems to have come from the reformers Huldrych Zwingli and Leo Jud and the printer Christoph Froschauer, who was interested in church politics.[39] Luther's already famous September Testament in Petri's Basel reprint of December 1523 was used for this purpose.[40] Petri's still rather cautious adaptations to his own "lantliche" language, which was highly valued by Swiss Humanism, are carried out much more consistently in the Zurich New Testament and are accompanied by a philologically precise examination of Luther's translation against the Greek text. Evidence suggests that Zwingli himself carried out this revision of Luther's translation for the Zurich printing.[41]

Use of the Worms prophets

The Wittenberg translation of the Old Testament initially made rapid progress. It was printed in Wittenberg in batches, always with subsequent reprints in Basel, which were then revised again for printing in Zurich. Froschauer's print of the historical books of the Old Testament (1524, according to Kolophon 1525) was accompanied by a Holy Land map, which goes back to a map by Lukas Cranach the Elder. It was inadvertently printed upside down in Zurich and is no longer found in later editions of Froschauer's Bible. But the Wittenberg circle of translators around Luther came to a standstill when it came to the books of the prophets. There were several reasons for this: The Farmers' War, Luther's illnesses, his dispute with Erasmus over free will and his Fight with Zwingli over the Lord's Supper left no capacity for translation work at times.[42] And so Luther was overtaken twice: in Worms and in Zurich.

The first translation of the books of the prophets into German was printed by Peter Schöffer in Worms in 1527: Alle Propheten / nach Hebraischer sprach verteutschet, the so-called Wormser Propheten. They were compiled by Ludwig Hätzer and Hans Denck, two humanists associated with the radical Reformation and the Anabaptist movement respectively. It is assumed that Hätzer and Denck were advised by Jewish scholars. Luther judged that although Hätzer and Denck had shown art and wisdom, they were not orthodox and therefore could not interpret faithfully.[43] Zwingli also acknowledged that Hätzer and Denck's translation was linguistically good and carefully crafted. Nevertheless, it should be turned away from with horror, as the authors were dangerous sectarians.[44] The Worms translation of the prophets sold very well. Zwingli therefore felt spurred on to produce his own orthodox translation of the prophets from Zurich - and to do so as quickly as possible. Among other things, he had a translation of the books of Isaiah and Jeremiah from Hebrew into Latin printed under his name as preparatory work.[45]

The extent to which the Worms Prophets were used as an aid for the Zurich translation of the prophets, completed in 1529, varied from book to book: according to Himmighöfer's analysis, the Book of Daniel is completely taken over from the Worms Prophets. In the Book of the Twelve Prophets, independently translated text passages alternate with sentences taken from the Worms Prophets; the latter were revised in a similar way to what the Zurich translators did with the Luther translation. In the books of Isaiah, Jeremiah (with Lamentations) and Ezekiel, the Zurich translation of the prophets was largely independent, but not without consulting the Worms Prophets. This can be explained by the fact that Froschauer wanted to supply the Frankfurt Spring Fair in 1529 with the Zurich translation of the prophets, which resulted in increasing time pressure for the translation work. The dependence on the Worms translation increased proportionally. The Book of Daniel was tackled last and had to be completed in just under three weeks - this was only possible thanks to text plagiarism.[46]

The Zurich translators could have used the Wittenberg translation of the prophets, which had appeared in the meantime, in their work, but this did not happen. Instead, "direct contact with Luther's translation was broken off: the dependence on the leading German Reformation translator came to an end with the Zurich Prophets".[47]

New translation of the poetic books

The poetic writings of the Old Testament include the books Job, Psalms, Book of Proverbs, Kohelet and Song of Songs. In 1525, Froschauer printed a Zurich adaptation of Petri's Basel reprint of the Wittenberg translation of these writings. This was limited to linguistic and dialectal adaptations; the Zurich edition offered hardly any alternative translations or glosses of its own devising. The reason for this is the difficulties of the Hebrew book of Job in particular, which they were apparently not yet prepared to tackle.[48] The author of the Job poem had a penchant for unusual words. They often only occur here in the Hebrew Bible (Hapax legomena).[49]

But with the Zurich Bible of 1531, the time had finally come: the people of Zurich were able to present a completely new translation of the poetic writings. Zwingli had done a series of preparatory work for this: in 1530 he produced a translation of the Book of Job into Latin. Special features of this Latin Job text can then be found in the Zurich Bible of 1531. "Here, as there, there is a close orientation to the wording of the Septuaginta preferred by Zwingli, in favor of which the Luther translation on the one hand and the Vulgata on the other must often take a back seat."[50] Terms that were theologically suspect to Zwingli, such as "blessed" and "bless", were deliberately avoided.[51] Zwingli had already translated the Psalms into German in 1525. This was a private manuscript in preparation for his series of sermons on the Psalms. This shows an orientation towards the Septuaginta-Psalter, whose numbering Zwingli adopted (Luther and most modern Bible translations follow the Hebrew Bible's Psalm numbering). The trace of Zwingli's translation of 1525 can be seen again and again in the Psalms of the Zurich Bible of 1531; one example (Ps 23:4 ZB):[52]

- Luther 1524: Und ob ich schon wandert ym finstern tal, furcht ich keyn ungluck

- Zwingli 1525: Und ob ich schon vergienge […] in dem […] goew des schattens des tods, so wird ich übels nit fürchten[53]

- Zürich 1531: Vnd ob ich mich schon vergienge in das goew des toedtlichen schattens/ so wurde ich doch nichts übels foerchten

In 1529, Zwingli once again translated the Psalms from Hebrew into Latin (printed posthumously in 1532). His knowledge of Hebrew, which had improved since 1525, is evident here, so that progress compared to the German version of 1525 is recognizable in many cases. The Zurich Bible of 1531 used both of Zwingli's translations, which were "critically compared, skillfully linked and for the most part adopted literally".[54]

Printing

The Dispensary Froschauer had been located in the Obmannamt, the former Barfüsserkloster, since 1528. Froschauer rented several rooms there from the council and had four printing presses in operation.[55]

The Zurich translation of the Bible was published in deliveries from 1524 to 1529 in folio form. The customer could have these parts bound together, as they were the same size, and was then in possession of a complete Bible in 1529. However, Froschauer did not print full Bibles with a complete title page until 1530.[56] After the circle of translators had completed their work in 1529, Froschauer initially printed the entire German Bible in 1530 without illustrations in octavo format. This was a handy, comparatively inexpensive edition of the Bible that could be carried with you when traveling.

In 1531, Froschauer then printed the Folio Bible as an expensive, magnificent edition. The printing template was a combination of various editions by Froschauer:[57]

- Pentateuch and history booksr: Full Bible in octavo (1530)

- Apocrypha: First printing of the Apocrypha in folio(1529)

- Poetic books: new translation that has completely broken away from the Luther Bible[58]

- Books of the Prophets: first printing of the Books of the Prophets in folio (1529)

- New Testament: Separate edition of the Zurich New Testament in octavo(1530)

A special feature of the Zurich Bible is that the Apocrypha are not placed between the Old and New Testaments as in the Luther Bible, but as an insertion within the Old Testament after the historical books and before the poetic books, i.e. between the Book of Esther and the Book of Job. The order of the Apocrypha differs from the Luther Bible, and the Zurich Bible of 1531 also contains more Apocrypha than the Luther Bible (3rd Book of Ezra, 4th Book of Ezra, 3rd Book of Maccabees). In the New Testament, the Zurich Bible adopted the order of the Luther Bible and moved Letter to the Hebrews and Letter of James behind the two letters of Peter and the three letters of John.[59]

Since the originals differed in terms of morphology and phonology, they were standardized for the Zurich Bible of 1531, while the vocabulary is more Upper German than in the full Bible of 1530. The latter was perhaps also intended for a clientele in Central Germany, while Froschauer wanted to appeal more to a Swiss clientele with the magnificent Bible of 1531.[60]

Scholarly gifts

A new preface, index and chapter summaries have been compiled for the 1531 Folio Bible. Parallel passages and glosses make the Bible text accessible.

- In the ten-page preface, an anonymous "we" addresses the reader. In the tradition of Erasmus, the reader is admonished to tune into the Bible reading so that he can take in the text calmly and without distraction. If they are confused by the content when reading, they should take their own ignorance into account; however, it could also be an error on the part of the printer. Reading the Bible is therefore about imparting knowledge. However, the help of the Holy Spirit is needed and the goal is eternal salvation.[61] Following the Edict of Worms, copies of the Luther Bible were confiscated and burned by Old Believers authorities and burned. The preface denounces Bible burnings as unchristian. Although individual mistranslations in Reformation Bibles could not be ruled out, these were inadvertent errors that did not justify the destruction of Holy Scripture. The fact that there were different Bible translations in the Protestant world should not irritate anyone. In church history, there had always been good times for Christianity in which every church had its own translation.[62] The relationship between the Zurich Bible and the Wittenberg translation is then determined: The Zurich scholars professed to have used Luther's Bible as the basis for the Pentateuch and the history books (in the New Testament too, but this is not mentioned at all). However, they had altered some literal passages according to our Upper Latvian German ... and rendered the meaning of various biblical passages clearer and more comprehensible - the judgment on this is left to the reader. The Masoretic vocalization of the Hebrew text and the commentaries of the rabbis are unreliable. The Greek textual tradition of the Septuagint is valuable, even if the Hebrew text deserves preference. The German translation of the Zurich Bible is not literal, as this would not make sense given the differences between the languages, and would be downright superstitious. To make reading the Bible more pleasant, beautiful new typefaces were used and illustrations added.[63] This is followed by a passage through the biblical books. The author is very much in the tradition of Erasmus here, as the Gospel is repeatedly described as a doctrine and rule of life. When reading the Bible, one encounters Jesus Christ in a personal way, just as a letter from a friend makes him present when reading.[64] Traditionally, Zwingli was considered the author of the preface. For stylistic reasons, Jürgen Quack assigns the preface to Leo Jud.[65] Traudel Himmighöfer also suspects that Jud, who was particularly familiar with the work of Erasmus, was the author.[66]

- The keyword index (ein kurtzer zeiger der fürnemsten hystorien vnnd gemeinsten articklen) was intended to be a practical aid to the reader when searching for specific biblical passages. It goes back to the Zeygerbüechlin der heiligen geschrifft by Jörg Berckenmeyer from Ulm, which Froschauer had been adding to his editions of the New Testament since 1525. It was revised and expanded for the Bible edition of 1531 and now comprised 8 ½ pages, "actually a miniature dogmatics for laymen".[67] The pointer lists the biblical references for around 650 keywords.[68] As Bible verses were not yet numbered consecutively, the Zurich Bible of 1531 divided the text of each chapter in most biblical books into paragraphs, which were labeled with Latin letters in the margins. In addition to Berckenmeyer's Zeygerbüechlin, the index also contains around 400 biblical place and personal names, comparable to the Concordantiae maiores in contemporary Vulgate editions.[68]

- An alphabetical index of the biblical books with their abbreviations shows the reader in which of the two parts and on which page the relevant biblical scripture begins in the Zurich Bible.

- The chapter summaries are short summaries of the contents that were printed in small type at the beginning of each chapter of most biblical books. They are an innovation in German-language Bible printing during the Reformation. The Old Testament prophetic books and Psalms are repeatedly referred to Jesus Christ in the chapter summaries.[69]

- There are almost 15,000 parallel biblical passages in the margin, which are intended to show in particular that the Old and New Testaments belong together, in accordance with Zwingli's Covenant Theology: "A single covenant unites the Old and New Testaments. There is only an accidental difference between the two; the Old and New Covenants do not differ in substance."[70]

- The few text glosses and around 1800 marginal glosses serve various purposes. They explain difficult terms, biblical names, foreign words or Helveticisms. For the humanistically educated public, the Zurich Bible of 1531 also provided references to rhetorical figures in the biblical text, referred to non-biblical ancient authors (above all Cicero and Josephus) around 70 times in the marginal glosses and explained difficult passages in terms of textual criticism. The reader's attention is often drawn to pedagogical and moral teachings from the biblical text by prompts such as notice, consider or lůg. In other sentential glosses, the Reformed theology and ethics presented themselves, while Catholic, Anabaptist or Lutheran views were corrected.[71]

Artistic equipment

The Zurich Bible of 1531, a two-column print with 50 lines per column, is unusually richly and exquisitely illustrated with two title woodcuts, a head woodcut (at the beginning of Genesis), 198 illustrations to the Bible text and 216 pictorial initials. According to F. Bruce Gordon, this printed Bible was a "feast for the eyes": "With its beautiful lettering, elegant marginalia and illustrations, this Bible could not be compared with anything that had previously been printed in Zurich. It was undoubtedly Froschauer's best work and the pinnacle of biblical scholarship in Zwingli's Zurich."[72]

Froschauer divided the Bible text into two roughly equal parts with separate pagination:[73]

- Pentateuch, history books, Apocrypha: 342 (CCCXLII) leaves

- Poetic writings, books of the prophets, New Testament: 322 (CCCXXII) leaves

Illustrations

Title woodcuts

The title page of the first part (Pentateuch, Books of History and Apocrypha) is attributed to Hans Leu the Younger from Zurich. The title of the book in red print and Froschauer's printer's mark are surrounded by a frame with twelve scenes from the creation story, divided by arcades and heightened in red. The drawing is very traditional and follows the model of the Lyon Vulgate of 1520. Froschauer had already used this frame for his edition of the Old Testament in 1525.[74]

The title page of the second part (poetic and prophetic books of the Old Testament and the New Testament) shows four scenes from the life of the Apostle Paul in a black and red frame, based on the Acts of the Apostles: conversion (left, cf. Acts 9:1-9 ZB), flight from Damascus (right, cf. Acts 9:25 ZB), transfer of the imprisoned Paul to Caesarea (bottom, cf. Acts 23:23-24 ZB) and shipwreck off Malta (top, cf. Acts 27:33-44 ZB). The drawing may be by Hans Asper, the woodcut by Veit Specklin. The transport of prisoners to Caesarea provides an opportunity to depict contemporary lansquenets and a cannon. Here, too, an older frame was reused, which Froschauer had already used in 1523 (Paraphrases of Erasmus) and 1524 (Zurich New Testament).[75]

Head woodcut for Genesis

The Genesis (Bible)/First Book of Moses is preceded by an illustration of the creation story that fills almost the entire width of the two columns of text. In Paradise (a forest teeming with various animal species), the oversized figure of the sleeping Adam can be seen in the foreground. Standing behind Adam, God the Father, depicted as a king with a wide cloak and crown, allows a much smaller Eve to emerge from Adam's side, turning towards God with her hands raised. God's left hand rests on Eve's head and he blesses her with his right handThe artist is thought to be Hans Asper, who in any case used a woodcut by Hans Springinklee as a model. "Everything appears somewhat stiff and is at best convincing due to the fine cross-strokes."[74]

Holbein's illustrations of the Old Testament

Froschauer ordered 118 illustrations of the Old Testament from Hans Holbein the Younger to explain the biblical text.[76] However, the choice of images is not necessarily pedagogical. It shows a preference for dramatic, violent and warlike scenes; the Book of Judges, the Book of Judith and the Books of Maccabees are therefore particularly richly illustrated.[77] The preface states that illustrations have been added to biblical stories in the hope of making the book fun and enjoyable to read.[78]

Holbein's drawings are in the tradition of the pictorial decoration of pre-Reformation German Bibles as well as contemporary vulgate prints. Above all, the Pentateuch and the historical books of the Old Testament were illustrated, as well as the Revelation of John in the New Testament; illustrations of the Gospels, on the other hand, were not common, apart from portraits of evangelists. 76 of the 118 Old Testament illustrations ordered by Froschauer are copies of Holbein's Icones, which were used in a Vulgate printed by the Trechsel brothers in Lyon in 1538 and intended for the Catholic market. This means that Holbein's (almost) identical illustrations adorn both the Reformed Zurich Bible and the Catholic Lyon Vulgate. The artist himself hardly positioned himself in the confessional dispute and followed the wishes of his patrons.[79]

Holbein's illustrations "are very close to the text within the traditional concepts. They combine simplicity, clarity and precision with the highest artistic skill."[80] An example of how Holbein illustrates a biblical narrative is the conflict depicted at the beginning of First Book of Samuel (1 Sam 1:1-8 ZB): The Israelite Elkanah has two wives, Hanna and Peninna. Hannah, whom he loves, is childless, but Peninnah has borne him children. Whenever Elkanah visits the shrine in Shiloh with his family, Peninna is given the opportunity to humiliate her rival. And now Holbein's illustration: Elkanah and Peninnah are sitting in an interior room on a wooden bench behind a table, with the two doves for the upcoming sacrifice in front of them. Both people turn to Hanna, who stands before them weeping and bent over: Peninna, sitting next to Hanna, is provocative, Elkanah encouraging, but speaking from a distance.[81]

By remaining true to the tradition of Bible illustration in his magnificent Bible of 1531, Froschauer also accepted traditional depictions of God that were in tension with the Reformed Ban on images. In the Zurich Bible of 1531, God the Father is regularly depicted as a bust portrait of a man with flowing hair and a full beard in a cloud or as a full-body figure of a king.[82] One example is the revelation of God described in chapter 3 of the Book of Exodus (Ex 3:1-5 ZB): A flock of sheep in the foreground indicates that Mose is on the way as a shepherd. In the background you can see a copse with a large cloud over it. In the middle of it bush on fire, and above it God appears as a bearded man holding out his left hand to Moses, apparently addressing him. Moses, completely oriented towards this apparition, is about to take off his shoes, as God has called him to do.

The anthropomorphism is particularly massive in the illustration for Psalm 109 (110):[83] Jesus Christ and God the Father (in the form of an old bearded man) are enthroned above the clouds, with the Holy Ghost hovering between them in the form of a dove. "That they [= the Zurich reformers] thus interpreted the psalm trinitarian is one thing, but that they dared to depict the Trinity traditionally in such a way is another."[84]

- 1 Samuel 1

- Exodus 3

- Psalm 109 (110)

Holbein's cycle on the Revelation of John

Froschauer commissioned a woodcut cycle on the Revelation of John from Holbein especially for the 1531 Bible. But this was not completed in time. Froschauer therefore had to resort to illustrations by the Basel printer Thomas Wolff to illustrate Revelation. Holbein had already produced the drawings used for a New Testament printed by Wolff in 1523. The woodcut cycle from the Cranach workshop in Luther's September Testament served him as a model; a special feature is the depiction of the New Jerusalem, in which one recognizes the city of Lucerne: the Museggmauer, the collegiate church and the Kapellbrücke with the Water Tower.[85]

Fonts

New, aesthetically pleasing, clear Schwabacher letters were produced, probably also cast in Froschauer's foundry. They have a type cone of 5.7 mm, 15 Punkt Didot. According to the classification of Konrad Haebler, this is a Schwabacher M81, which ensures very good legibility.[86] The chapter headings are in Fraktur (22 point Didot), the table of contents below in a small Schwabacher (10 point Didot). For the page headings, the Froschauer Offizin used "Fraktur in Canon font size with slightly decorated capitals", for the parallel biblical passages in the margins "Antiqua italics with upright capitals".[87]

Sale

The colophon of the first part dates the printing to May 12, 1531. There is no such note for the second part, but it can be assumed that it was printed around the same time. The careful execution took several weeks. The Zurich Magnificent Bible was therefore probably not put on sale until the Frankfurt Autumn Fair in 1531.[88] The circulation was at least 3000 copies.[89] This magnificent bound Bible cost 3 ½ guilders or 7 pounds, plus a batzen for the bookbinder (1 guilder = 2 pounds = 16 batzen).[90] Although their price was high - more than half a month's wages for a master craftsman in Zurich[91] -, the first edition of the Zurich Bible sold quickly.

Reception history

Luther claimed his translation of the Bible as a kind of intellectual property (legally, the 16th century did not yet know this term). Although the Luther Bible was revised in Wittenberg until Luther's death, Luther presided over the process and decided on the changes. Therefore, the unauthorized revision that took place in Zurich could not have been approved by him.[92] He repeatedly made disparaging remarks about the various parts and editions of the Zurich Bible. He called Leo Jud's translation of the Apocrypha insignificant (mirum quam nihili sunt), and the particularly difficult translation of the books of the Prophets, with which the Zurich translators had beaten the Wittenbergers, showed Zwingli's arrogance (translatio superbissima). Zwingli, whom Luther regarded as the main translator, lacked respect for the princes. In the preface of 1531, the people of Zurich expressed their astonishment at Luther's criticism. In their opinion, by using Luther's Bible, they were showing respect for the work of the Wittenbergers. For changing the vocabulary here and there and finding better formulations, the "interpreter" (= Luther) should have loved them and not hated them - if he was only concerned with the glory of God.[93] For Zwingli and his circle of collaborators, only the Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek texts were Scriptures; translations were to compete to capture the meaning of the text as well as possible. Their comparison is instructive. This is reminiscent of the Bible lessons of the Prophets, where translations were produced and discussed in front of an audience.[94]

While Luther's Bible in its "last hand" version was treasured over the centuries after Luther's death as a kind of legacy of the reformer, Zwingli's death in the Battle of Kappel (October 11, 1531) did not result in a corresponding appreciation for the Zurich Bible of 1531. In keeping with Zwingli's intentions, work on the Prophezei continued; Zwingli's part was taken over by Theodor Bibliander. Froschauer printed further Bibles in German and Latin, a Greek New Testament (1547) and an English Bible (1550). For the German Folio Bible of 1539/40, Michael Adam, a converted Jew, thoroughly revised the translation of the Old Testament. After the end of Bibliander's work at the Prophecy in 1560, the Zurich Bibles increasingly came under calvinist influence. Calvinist influence.[95]

Text editions

- Die gantze Bibel / der ursprünglichen ebraischen und griechischen Waarheyt nach auffs aller treüwlichest verteütschet. Reduced facsimile edition of the copy in the Zentralbibliothek Zürich, with an afterword by Hans Rudolf Lavater: Die Zürcher Bibel 1531 – Das Buch der Zürcher Kirche. TVZ, Zürich 1983.

- Jch bin das brot des läbens. Neues Testament und Psalmen. Wortlaut der Froschauer-Bibel 1531 und Übersetzung der Zürcher Bibel 2007. Published by the Protestant parish of Grossmünster. TVZ, Zürich 2018, ISBN 978-3-290-18175-8.

- Es werde liecht. Altes Testament. Wortlaut der Froschauer-Bibel 1531 und Übersetzung der Zürcher Bibel 2007. Published by the Protestant parish of Grossmünster. 2 volumes.TVZ, Zürich 2022, ISBN 978-3-290-18506-0.

Literature

Anthologies

- Martin Rüsch, Urs B. Leu (Ed.): Getruckt zů Zürich: ein Buch verändert die Welt. Orell Füssli, Zürich 2019, ISBN 978-3-280-05703-2.

- Christoph Sigrist (Ed.): Die Zürcher Bibel von 1531: Entstehung, Verbreitung und Wirkung. TVZ, Zürich 2011, ISBN 978-3-290-17579-5.

Articles and monographs

- Jan-Andrea Bernhard: Die Prophezei (1525–1532) – Ort der Übersetzung und Bildung. In: Martin Rüsch, Urs B. Leu (Ed.): Getruckt zů Zürich: ein Buch verändert die Welt. Orell Füssli, Zürich 2019, p. 93–113.

- Christine Christ-von Wedel: Zu den Illustrationen in den Zürcher Bibeln. In: Martin Rüsch, Urs B. Leu (ED.): Getruckt zů Zürich: ein Buch verändert die Welt. Orell Füssli, Zürich 2019, p. 115–136.

- Werner Besch: Lexikalischer Wandel in der Zürcher Bibel. Eine Längsschnittstudie. In: Vilmos Ágel, Andreas Gardt, Ulrike Haß-Zumkehr, Thorsten Roelcke (Hrsg.): Das Wort – Seine strukturelle und kulturelle Dimension. Festschrift für Oskar Reichmann zum 65. Geburtstag. De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston 2011, p. 279–296.

- Hans Byland: Der Wortschatz des Zürcher Alten Testaments von 1525 und 1531 verglichen mit dem Wortschatz Luthers. Berlin 1903 (Digitalisat).

- Emil Egli: Zwingli als Hebräer. In: Zwingliana 1/8, 1900, p. 153–158.

- Walter Haas: Etliche wörtly geenderet: Luthers Bibel und die Zürcher Bearbeitung. In: Norbert Richard Wolf (Hrsg.): Martin Luther und die deutsche Sprache – damals und heute. Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2017, ISBN 978-3-8253-6814-2, p. 167–186.

- Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531): Darstellung und Bibliographie. (= Publications of the Institute of European History Mainz, Department of Religious History, Volume 154). Von Zabern, Mainz 1995, ISBN 978-3-8053-1535-7. Digitalisat

- Wilfried Kettler: Die Zürcher Bibel von 1531. Philologische Studien zu ihrer Übersetzungstechnik und den Beziehungen zu ihren Vorlagen. Peter Lang, Bern u. a. 2001, ISBN 978-3-906755-74-8.

- Hans Rudolf Lavater-Briner: Die Froschauer-Bibel 1531. In: Christoph Sigrist (Hrsg.): Die Zürcher Bibel von 1531: Entstehung, Verbreitung und Wirkung. TVZ, Zürich 2011, p. 64–170.

- Paul Leemann-van Elck: Der Buchschmuck der Zürcher Bibeln bis 1800: nebst Bibliographie der in Zürich bis 1800 gedruckten Bibeln, Alten und Neuen Testamente. Bern 1938.

- Paul Leemann-van Elck: Die Offizin Froschauer, Zürichs berühmte Druckerei im 16. Jahrhundert: ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Buchdruckerkunst anlässlich der Halbjahrtausendfeier ihrer Erfindung. Orell Füssli, Zürich 1940.

- Urs B. Leu: Die Froschauer-Bibeln und ihre Verbreitung in Europa und Nordamerika. In: Christoph Sigrist (Hrsg.): Die Zürcher Bibel von 1531: Entstehung, Verbreitung und Wirkung. TVZ, Zürich 2011, p. 26–63.

- Herbert Migsch: Huldreich Zwinglis hebräische Bibel. In: Zwingliana. 32, 2005, p. 39–44.

- Herbert Migsch: Noch einmal: Huldreich Zwinglis hebräische Bibel. In: Zwingliana. 36, 2009, p. 41–48.

- George R. Potter: Zwingli and the Book of Psalms. In: The Sixteenth Century Journal. 10/2, 1979, p. 42–50.

- Jürgen Quack: Evangelische Bibelvorreden von der Reformation bis zur Aufklärung. Mohn, Gütersloh 1975.

- Walter Schenker: Die Sprache Huldrych Zwinglis im Kontrast zur Sprache Luthers. De Gruyter, Berlin/New York 1977.

External links

- Digitalisat of the hand-colored copy in the Grossmünster Zurich on e-rara

References

- ^ Heinrich Bullinger: Reformationsgeschichte. Edited by J. J. Hottinger and H. H. Vögeli. Volume 1, Frauenfeld 1838, p. 306.

- ^ Schweizerisches Idiotikon, Volume III, column 1306, article landlich, meaning 4: "according to the country (also in contrast to the city), customary, popular, simple"; landlich mit einem reden, "in the simple vernacular» (Digitalisat).

- ^ Walter Schenker: Die Sprache Huldrych Zwinglis im Kontrast zur Sprache Luthers. Berlin/New York 1977, p. 11.

- ^ Walter Haas: Kurze Geschichte der deutschen Schriftsprache in der Schweiz. In: Hans Bickel, Robert Schläpfer (Ed.): Die viersprachige Schweiz (= Reihe Sprachlandschaft. Band 25). Sauerländer, Aarau/Frankfurt am Main/Salzburg 2000, pp. 109-138, here 115.

- ^ Hans Rudolf Lavater-Briner: Die Froschauer-Bibel von 1531. Zürich 2011, p. 75–77; Walter Haas: Etliche wörtly geenderet: Luthers Bibel und die Zürcher Bearbeitung. Heidelberg 2017, p. 174 and note 13.

- ^ Werner Besch: Deutscher Bibelwortschatz in der frühen Neuzeit: Auswahl – Abwahl – Veralten. Lang, Frankfurt am Main u. a. 2008, p. 19.

- ^ Wilfried Kettler: Die Zürcher Bibel von 1531. Philologische Studien zu ihrer Übersetzungstechnik und den Beziehungen zu ihren Vorlagen. Bern u. a. 2001, p. 474.

- ^ Hans Rudolf Lavater-Briner: Die Froschauer-Bibel 1531. Zürich 2011, p. 82.

- ^ Walter Haas: Kurze Geschichte der deutschen Schriftsprache in der Schweiz. In: Hans Bickel, Robert Schläpfer (Hrsg.): Die viersprachige Schweiz (= Reihe Sprachlandschaft. Volume 25). Sauerländer, Aarau/Frankfurt am Main/Salzburg 2000, pp. 109-138, here 117.

- ^ Walter Haas: Etliche wörtly geenderet: Luthers Bibel und die Zürcher Bearbeitung. Heidelberg 2017, p. 174.

- ^ Hans Rudolf Lavater-Briner: Die Froschauer-Bibel 1531. Zürich 2011, p. 80.

- ^ Walter Schenker: Die Sprache Huldrych Zwinglis im Kontrast zur Sprache Luthers. Berlin/New York 1977, p. 83 f.

- ^ Walter Haas: Etliche wörtly geenderet: Luthers Bibel und die Zürcher Bearbeitung. Heidelberg 2017, p. 176.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 428 f.

- ^ Jan-Andrea Bernhard: Die Prophezei (1525–1532) – Ort der Übersetzung und Bildung. Zürich 2019, p. 95–99.

- ^ Wilfried Kettler: Die Zürcher Bibel von 1531. Philologische Studien zu ihrer Übersetzungstechnik und den Beziehungen zu ihren Vorlagen. Bern u. a. 2001, p. 99, 112.

- ^ Wilfried Kettler: Die Zürcher Bibel von 1531. Philologische Studien zu ihrer Übersetzungstechnik und den Beziehungen zu ihren Vorlagen. Bern u. a. 2001, p. 467. Vgl. Walter Schenker: Die Sprache Huldrych Zwinglis im Kontrast zur Sprache Luthers. Berlin/New York 1977, p. 27: «Redaktionskollektiv der Prophezei».

- ^ Walter Schenker: Die Sprache Huldrych Zwinglis im Kontrast zur Sprache Luthers. Berlin/New York 1977, p. 95.

- ^ a b Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 427.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 428.

- ^ Herbert Migsch: Noch einmal: Huldreich Zwinglis hebräische Bibel. 2009, p. 42 f.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 192 f.

- ^ George R. Potter: Zwingli and the Book of Psalms. 1979, p. 45.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 106 f.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 107.

- ^ Hans Rudolf Lavater-Briner: Die Froschauer-Bibel 1531. Zürich 2011, p. 98 f.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 147.

- ^ Hans Rudolf Lavater-Briner: Die Froschauer-Bibel 1531. Zürich 2011, p. 81.

- ^ Walter Schenker: Die Sprache Huldrych Zwinglis im Kontrast zur Sprache Luthers. Berlin/New York 1977, p. 73.

- ^ Walter Haas: Etliche wörtly geenderet: Luthers Bibel und die Zürcher Bearbeitung. Heidelberg 2017, p. 175.

- ^ Wilfried Kettler: Die Zürcher Bibel von 1531. Philologische Studien zu ihrer Übersetzungstechnik und den Beziehungen zu ihren Vorlagen. Bern u. a. 2001, p. 473.

- ^ Wilfried Kettler: Die Zürcher Bibel von 1531. Philologische Studien zu ihrer Übersetzungstechnik und den Beziehungen zu ihren Vorlagen. Bern u. a. 2001, p. 476.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 423.

- ^ Wilfried Kettler: Die Zürcher Bibel von 1531. Philologische Studien zu ihrer Übersetzungstechnik und den Beziehungen zu ihren Vorlagen. Bern u. a. 2001, p. 78.

- ^ Walter Haas: Etliche wörtly geenderet: Luthers Bibel und die Zürcher Bearbeitung. Heidelberg 2017, p. 172.

- ^ Walter Haas: Etliche wörtly geenderet: Luthers Bibel und die Zürcher Bearbeitung. Heidelberg 2017, p. 169 f.

- ^ Phonology: retraction of the New High German diphthongization and monophthongization; morphology: apocope of the ending -e (example: ich sag euch instead of ich sage euch); in individual cases, replacement of an incomprehensible East Central German word. Cf. Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 64.

- ^ Quoted here from Wilfried Kettler: Die Zürcher Bibel von 1531. Philologische Studien zu ihrer Übersetzungstechnik und den Beziehungen zu ihren Vorlagen. Bern u. a. 2001, p. 77.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 83.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 85.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 86, 99.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 296.

- ^ Martin Luther: Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen (= Weimarer Ausgabe. Band 30). p. 640 (online).

- ^ Huldrych Zwingli: Vorrede zur Prophetenbibel (= Huldreich Zwinglis sämtliche Werke. Band 6.2). Berichthaus, Zurich 1968, pp. 289-312, here 289 f.: Dann obglych vormaals ein vertolmetschung der propheten ußgangen, ward doch dieselbe vonn vilen einvaltigen unnd guothertzigen (als von den widertoeufferen ußgangen) nit wenig geschücht, wiewol dieselbe, so vil wir darinn geläsen, an vil orten flyssig unnd getrüwlich naach dem ebreischen buochstaben vertütscht ist. Wäm wolt aber nit schühen und grusen ab der vertolmetschung, die von denen ußgangen ist, die die rechten rädlyfuerer warend der säckten unnd rotten, die unns uff den hüttigen tag in der kilchen gottes mee unruow gestattet, dann das bapstuomb ye gethon hatt? (online).

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 302.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 325–329.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 331.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 208–212.

- ^ Cf. for example Frederick E. Greenspahn: The Number and Distribution of Hapax Legomena in Biblical Hebrew. In: Vetus Testamentum. 30/1, 1980, p. 8–19, here 15 f.: Job […] includes a higher proportion of hapax legomena than any other biblical book, yet the prose sections and Zophar speeches are quite average in their use of unique words while Eliphaz, Bildad, and Elihu speeches contain a large, but not overwhelming proportion of hapax legomena. […] However, Job’s speeches, if treated separately, have a higher proportion of hapax legomena than any biblical book other than Job itself, while the divine speeches rank even higher than the work in which they are contained!

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 396.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 397.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 398.

- ^ Vgl. Ulrich Zwingli: Übersetzung der Psalmen. Zürich 1525. Zentralbibliothek Zürich, Ms Car C 37, fol. 30 v (Digitalisat).

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 401.

- ^ Paul Leemann-van Elck: Die Offizin Froschauer, Zürichs berühmte Druckerei im 16. Jahrhundert: ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Buchdruckerkunst anlässlich der Halbjahrtausendfeier ihrer Erfindung. Zürich 1940, p. 73 f.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 357.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 391.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 393 f.

- ^ Wilfried Kettler: Die Zürcher Bibel von 1531. Philologische Studien zu ihrer Übersetzungstechnik und den Beziehungen zu ihren Vorlagen. Bern u. a. 2001, p. 113–116.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 391 f.

- ^ Jürgen Quack: Evangelische Bibelvorreden von der Reformation bis zur Aufklärung. Gütersloh 1975, p. 61–64.

- ^ Jürgen Quack: Evangelische Bibelvorreden von der Reformation bis zur Aufklärung. Gütersloh 1975, p. 64–66.

- ^ Jürgen Quack: Evangelische Bibelvorreden von der Reformation bis zur Aufklärung. Gütersloh 1975, p. 66 f.

- ^ Jürgen Quack: Evangelische Bibelvorreden von der Reformation bis zur Aufklärung. Gütersloh 1975, p. 67–70.

- ^ Jürgen Quack: Evangelische Bibelvorreden von der Reformation bis zur Aufklärung. Gütersloh 1975, p. 60.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 382–386.

- ^ Hans Rudolf Lavater-Briner: Die Froschauer-Bibel 1531. Zürich 2011, p. 120.

- ^ a b Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 386.

- ^ Hans Rudolf Lavater-Briner: Die Froschauer-Bibel 1531. Zürich 2011, p. 122.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 401 f.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 401–405.

- ^ F. Bruce Gordon: Zwingli – God’s Armed Prophet. Yale University Press, New Haven/London 2021, p. 240: “The volume, a delight to the eye, opened with a title page graced by a Hans Holbein woodcut of 12 scenes from the creation of the world. With its beautiful type, elegant marginal notes and illustrations, this Bible was unlike anything hitherto produced in Zurich. Without doubt it was Froschauer’s finest work and the very summit of biblical scholarship in Zwingli’s Zurich.”

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 370 f.

- ^ a b Hans Rudolf Lavater-Briner: Die Froschauer-Bibel 1531. Zürich 2011, p. 130 f.

- ^ Hans Rudolf Lavater-Briner: Die Froschauer-Bibel 1531. Zürich 2011, p. 130 f.

- ^ Jan Rohls: Reformation und Gegenreformation (= Kunst und Religion zwischen Mittelalter und Barock. Band 2). De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston 2021, p. 59

Hans Rudolf Lavater-Briner: Die Froschauer-Bibel 1531. Zürich 2011, p. 136. - ^ Christine Christ-von Wedel: Bilderverbot und Bibelillustrationen im reformierten Zürich. In: Peter Opitz (Ed.): The Myth of the Reformation. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2013, p. 299–320, here 301 f.

- ^ Christine Christ-von Wedel: Zu den Illustrationen in den Zürcher Bibeln. Zürich 2019, p. 122, 133.

- ^ Hans Rudolf Lavater-Briner: Die Froschauer-Bibel 1531. Zürich 2011, p. 136 f.

Christine Christ-von Wedel: Zu den Illustrationen in den Zürcher Bibeln. Zürich 2019, p. 119. - ^ Christine Christ-von Wedel: Zu den Illustrationen in den Zürcher Bibeln. Zürich 2019, p. 120.

- ^ Vgl. ausserdem Hanna und Elkana, Pen and ink drawing after Hans Holbein the Younger, Graphische Sammlung der Zentralbibliothek Zürich, ZEI 1.0016.013 (Digitalisat bei e-manuscripta).

- ^ Christine Christ-von Wedel: Bilderverbot und Bibelillustrationen im reformierten Zürich. In: Peter Opitz (Hrsg.): The Myth of the Reformation.Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2013, pp. 299-320, here 308 and note 43.

- ^ For the Psalms, the Zurich Bible of 1531 adopts the numbering of the Vulgate, but adds the numbering of the Hebrew text (and the Luther Bible) in smaller print.

- ^ Christine Christ-von Wedel: Bilderverbot und Bibelillustrationen im reformierten Zürich. In: Peter Opitz (Hrsg.): The Myth of the Reformation. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2013, pp. 299-320, here 301 f.

- ^ On the Lucerne vignette, see for example Friedrich Salomon Vögelin: Ergänzungen und Nachweisungen zum Holzschnittwerk Hans Holbeins des Jüngeren. In: Repertorium für Kunstwissenschaft. Volume 2. photomechanical reprint, de Gruyter, Berlin 1968, pp. 162-190, here 178.

- ^ Paul Leemann-van Elck: Der Buchschmuck der Zürcher Bibeln bis 1800. Bern 1938, p. 36.

- ^ Hans Rudolf Lavater-Briner: Die Froschauer-Bibel 1531. Zürich 2011, p. 169 und Anm. 221.

- ^ Paul Leemann-van Elck: Der Buchschmuck der Zürcher Bibeln bis 1800. Bern 1938, p. 34.

- ^ Paul Leemann-van Elck: Der Buchschmuck der Zürcher Bibeln bis 1800. Bern 1938, p. 59: "It probably amounted to at least 3000 copies of the present Bible, but later reached 6000 copies."

- ^ Paul Leemann-van Elck: Die Offizin Froschauer, Zürichs berühmte Druckerei im 16. Jahrhundert: ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Buchdruckerkunst anlässlich der Halbjahrtausendfeier ihrer Erfindung. Zurich 1940, p. 66. On the Zurich currency, see Christoph Sigrist (ed.): Die Zürcher Bibel von 1531: Entstehung, Verbreitung und Wirkung. Zurich 2011, p. 152 and note 8.

- ^ Urs B. Leu: Die Froschauer-Bibeln und ihre Verbreitung in Europa und Nordamerika. Zürich 2011, p. 28.

- ^ Walter Haas: Etliche wörtly geenderet: Luthers Bibel und die Zürcher Bearbeitung. Heidelberg 2017, p. 176–179.

- ^ Wilfried Kettler: Die Zürcher Bibel von 1531. Philologische Studien zu ihrer Übersetzungstechnik und den Beziehungen zu ihren Vorlagen. Bern u. a. 2001, p. 117 f.

- ^ Walter Haas: Etliche wörtly geenderet: Luthers Bibel und die Zürcher Bearbeitung. Heidelberg 2017, p. 177–179.

- ^ Traudel Himmighöfer: Die Zürcher Bibel bis zum Tode Zwinglis (1531). Mainz 1995, p. 428–432. Vgl. Walter Haas: Etliche wörtly geenderet: Luthers Bibel und die Zürcher Bearbeitung. Heidelberg 2017, p. 181: "Luther's Bible had become a canonical text and his language was therefore no longer an ordinary language. It remained an exemplary, even sacred language beyond the time of its 'secular' validity. [...] The Zurich Bible escaped the canonical fate ...".