Al-Zaytuna Mosque

| Al-Zaytuna Mosque | |

|---|---|

جامع الزيتونة | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Branch/tradition | Sunni |

| Location | |

| Location | Tunis, Tunisia |

| Geographic coordinates | 36°47′50″N 10°10′16″E / 36.7972°N 10.1711°E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Fathallah (Fath al-Banna') |

| Type | Mosque |

| Style | Moorish (Aghlabid and other periods) |

| Date established | 698 CE |

| Completed | 864 CE (with later additions) |

| Specifications | |

| Minaret(s) | 1 |

| Minaret height | 43 meters (141 ft 1 in) |

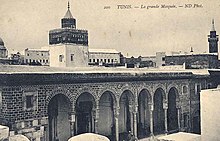

Al-Zaytuna Mosque, also known as Ez-Zitouna Mosque, and El-Zituna Mosque (Arabic: جامع الزيتونة, literally meaning the Mosque of Olive), is a major mosque at the center of the Medina of Tunis in Tunis, Tunisia. The mosque is the oldest in the city and covers an area of 5,000 square metres (1.2 acres) with nine entrances.[1] It was founded at the end of the 7th century or in the early 8th century, but its current architectural form dates from a reconstruction in the 9th century, including many antique columns reused from Carthage, and from later additions and restorations over the centuries.[2][3]

The mosque developed into a place of higher education, today the University of Ez-Zitouna, which became the most important educational institution in Tunisia from around the 13th century onward.[2] Ibn 'Arafa, a major Maliki scholar, al-Maziri, the great traditionalist and jurist, and Aboul-Qacem Echebbi, a famous Tunisian poet, all taught there, among others.[1][4][5]

Etymology

One legend states that it was called "Mosque of Olive" because it was built on an ancient place of worship where there was an olive.[citation needed] Another account, transmitted by the 17th century Tunisian historian Ibn Abi Dinar,[3] reports the presence of a Byzantine Christian church dedicated to Santa Olivia at that location.[2][3] Archeological investigations and restoration works in 1969–1970 have shown that the mosque was built over an existing Byzantine-era building with columns, covering a cemetery.[2] This may have been a Christian basilica, which provides support for the legend reported by Ibn Abi Dinar.[3] A more recent interpretation by Muhammad al-Badji Ibn Mami suggests that the previous structures may have been part of a Byzantine fortification, inside which the Arab conquerors built their mosque.[2] This hypothesis is also supported by Sihem Lamine.[6]

The saint is particularly venerated in Tunisia because it is superstitiously thought that if the site and its memory are profaned then a misfortune will happen; this includes a belief that when her relics are recovered Islam will end.[7] This ancillary legend related to the discovery of the saint's relics is widespread in Sicily, however it is connected to other Saints as well.[8] In 1402 king Martin I of Sicily requested the return of Saint Olivia's relics from the Berber Caliph of Ifriqiya Abu Faris Abd al-Aziz II, who refused him.[9] Even today the Tunisians, who still venerate her, believe that the dominion of their religion will fade when the body of the Virgin Olivia will disappear.[9]

History

Foundation

Al-Zaytuna was the second mosque to be built in Ifriqiya and the Maghreb region after the Mosque of Uqba in Kairouan.[4] The exact date of building varies according to different sources and interpretations. The 11th-century writer Al-Bakri wrote that Ubayd Allah ibn al-Habhab, the Umayyad governor of Ifriqiya, built a Friday mosque (jāmīʿ) in Tunis in 114 Hijri (732–733 CE).[2] Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406) also repeats this account.[4] However, al-Bakri also mentions a mosque (masjid) being built by Hasan ibn al-Nu'man, who led the conquest of Carthage, in 79 Hijri (circa 698 CE).[2]

Modern historians have been divided over the exact date of construction and on whether it should be attributed to Ibn al-Habhab or to Ibn al-Nu'man.[2][4] Most scholars support the second explanation[2][4] and attribute the foundation to Ibn al-Nu'man in 698 CE.[6][10][11] Under this explanation, it is assumed that Ibn al-Habhab subsequently rebuilt it, expanded it, or completed its construction.[2][10][6][4][12] One supporting argument is that it is unlikely the city of Tunis remained a long time without a mosque after its conquest in 79 Hijri.[4] Ahmed ibn Abu Diyaf, a 19th-century Tunisian historian, attributes the foundation to Hasan ibn al-Nu'man in 84 Hijri (703 CE).[4] Lucien Golvin, a 20th-century French scholar, argued that Ibn al-Habhab was the founder but that the construction took place in 116 Hijri (734–735 CE).[13]

Aghlabid reconstruction

The mosque owes its current overall form to a reconstruction under the Aghlabids, the dynasty that ruled Ifriqiya on behalf of the Abbasid caliphs in the 9th century. The work was begun during the reign of emir Abu Ibrahim Ahmad and completed in 864–865.[14]: 38–40 [6][3] As a result, the mosque's layout is also very similar to the Mosque of Uqba in Kairouan, which was also rebuilt by the Aghlabids earlier in the same century.[14]: 38–41 A contemporary inscription at the base of the dome in front of the mihrab gives the date of this construction and names three individuals: 1) the Abbasid caliph al-Musta'in Billah, identified as the main patron;[6] 2) Nusayr, a mawla of the caliph and probably the overseer of the works;[6] and 3) Fathallah or Fath al-Banna', the architect and chief builder.[3][6] Another inscription, along one of the mosque's courtyard façades, provides the same information.[6] The Aghlabid emir himself (Abu Ibrahim Ahmad) is not mentioned in these inscriptions, suggesting that he may not have been officially involved in the construction and that Nusayr was directing the works directly on behalf of the Abbasid caliph instead.[6]

The Aghlabid structure, in turn, is mostly obscured today by later additions and reconstructions. The sections that are best preserved from the 9th century are the interior of the prayer hall (though some of this was later rebuilt too) and the projecting round corner bastions at the northern and eastern corners of the mosque.[14]: 38–40 There is no evidence that a minaret was attached to the mosque at this time. The reasons for this omission are unclear. It suggests that minarets were not yet a standard feature of congregational mosques[14]: 41 or that they were still considered a controversial innovation at the time.[6]

Later history

Between 990 and 995 further works were carried out under the Zirids, clients of the Fatimid caliphs. These works included the addition of galleries around the courtyard[2] and the Qubbat al-Bahu (or Qubbat al-Bahw), the dome at the entrance of the prayer hall. The dome itself is dated more specifically to 991.[14]: 86–87 [6] The dates for these works are provided by a series of inscriptions around the Qubbat al-Bahu, but the names of the patrons themselves were erased at a later period,[6] possibly when the Zirids declared independence from the Fatimids in the 11th century.[14]: 87 From context, the works can be attributed to the patronage of the Zirid emir Al-Mansur ibn Buluggin.[14]: 86–87 [6] The inscriptions also provide the names of four craftsmen: Ahmad al-Burjini, Abu al-Thana, 'Abdallah ibn Qaffas, and Bishr ibn al-Burjini.[14]: 87

Under the Hafsids, who ruled during the 13th to 15th centuries, Tunis became the main capital of Ifriqiya for the first time. This led to an increase in the Zaytuna Mosque's importance and allowed it to overtake the prestige of the older Mosque of Uqba in Kairouan.[2] Significant restoration work was carried out by the Hafsid rulers, under al-Mustansir in 1250 and under Abu Yahya Zakariya in the early 14th century, adding features such as ablution facilities and replacing some of the woodwork.[14]: 209 [11] Other repairs and restorations were carried at multiple points during this era.[2] The mosque's first attested minaret was also built under Hafsid patronage in 1438–1439.[2][6] Its appearance is known from old photographs: it had a cuboid shape (having a shaft with a square base) and was crowned with an arcaded gallery and a polygonal turret or lantern at its summit.[14]: 225

In 1534 Spanish forces occupied Tunis and broke into the mosque, raiding its libraries and destroying or dispersing many of its manuscripts.[15][2] During the Ottoman period, both the Muradid and Husaynid dynasties restored and expanded the mosque and its associated institutions.[15] This helped restore the mosque's prominence and its prestige as a center of learning.[15] In 1637 an arcaded loggia was added to the mosque's exterior eastern façade by a patron named Muhammad al-Andalus ibn Ghalib, whose name suggests he was one of the moriscos expelled from Spain in 1609.[14]: 220 From 1624 to 1812 the local Bakri family took charge of the mosque's care and occupied the position of the mosque's imam.[15] The present-day minaret was entirely rebuilt in 1894 and imitates the Almohad style of the Kasbah Mosque's minaret further west.[3][14]: 225 Tunisian presidents Bourguiba and Ben Ali carried out major restoration work and rehabilitation, especially during the 1960s and 1990s.[16]

Scholarship and the University

There is little information about teaching at the Zaytuna Mosque prior to the 14th century. During this time there were most likely courses being offered voluntarily by ulama (Islamic legal scholars), but not in an organized manner.[2] For centuries, Kairouan was the early centre of learning and intellectual pursuits in Tunisia and North Africa in general. Starting from the 13th century, Tunis became the capital of Ifriqiya under Almohad and Hafsid rule.[15] This shift in power helped al-Zaytuna to flourish and become one of the major centres of Islamic learning, and Ibn Khaldun, the first social historian in history was one of its products.[17] The flourishing university attracted students and men of learning from all parts of the known world at the time. Along with disciplines theology – such as exegesis of the Qur'an (tafsir) – the university taught fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), Arabic grammar, history, science and medicine.[15][2] It also had a kuttab or elementary school that taught youth how to read, write, and memorize religious texts.[15] The system of teaching was not rigid: attendance was not mandatory and students could follow the courses of their choice. Students who followed a course and became knowledgeable enough to teach the subject on their own were granted a certificate called an ijazah by their instructor.[2]

Rich libraries were also attached to the university. The manuscripts covered almost all subjects and sciences, including grammar, logic, documentations, etiquette of research, cosmology, arithmetic, geometry, minerals, vocational training, etc.[18][19] One of its famous libraries, al-Abdaliyah, included a large collection of rare manuscripts that attracted scholars from abroad.[15] Much of the library's original collection was dispersed or destroyed when the Spanish occupied Tunis and broke into the Zaytuna Mosque in 1534.[2][15] After Tunisia gained independence from France in the 1950s the university's library was integrated into the National Libraries of Tunis.[2]

The start of Ottoman rule in 1574 initially brought a decline in teaching, but this quickly recovered.[2] The institution received greater attention and political patronage in the 18th century. By this time, however, the teaching of non-religious subjects had significantly declined.[2] Administrative and curricular reforms to the institution were begun by Ahmad Bey in 1842. They continued in 1875 under Prime Minister Khayr al-Din al-Tunisi, who also expanded the al-Abdaliyah Library and opened it to the public. In 1896 new courses were introduced such as physics, political economy, and French, and in 1912 these reforms were extended to the university's other branches in Kairouan, Sousse, Tozeur, and Gafsa.[15] Until the 20th century the students were mostly recruited from Tunisia's wealthiest families but afterwards its recruitment broadened. Under French colonial rule it turned into a bastion of Arab and Islamic culture resisting French influence. Some prominent members of the Algerian nationalist movement studied here, such as 'Abd al-Hamid ibn Badis, Tawfiq Madani, and Houari Boumédiène.[15]

After independence from France, reforms to the education system in 1958 and the creation of the University of Tunis in 1960 reduced the Zaytuna's importance.[15] In 1964–1965 its status as an independent university was abolished by President Habib Bourguiba and it was relegated to being a theological college for the University of Tunis.[15][20] For years afterward, under the rule of both Bourguiba and his successor Ben Ali, the Zaytuna educational institution was kept officially and physically distinct from the Zaytuna Mosque itself.[21]: 42 In 2012, after the Tunisian revolution and in response to a court petition by a group of Tunisian citizens, the mosque's former educational offices were reopened and it was declared an independent educational institution once again.[21]: 49 [20][22]

Architecture

General layout

The al-Zaytuna Mosque followed the design and architecture of previous mosques, particularly the Mosque of Uqba in Kairouan that was built in its current form a few decades earlier.[14]: 41 The layout of the building and its interior is irregular, with many of its lines not quite parallel or perpendicular, but this is not perceptible to a visitor.[14]: 38–39 The building consists primarily of a trapezoidal courtyard (sahn) and a hypostyle prayer hall. The main difference between this mosque and the Kairouan mosque is the position of the minaret, which in this case was added at a much later period.[14]: 41

The mosque is closely integrated into the urban fabric and most of the building's exterior is concealed by other neighbouring structures. Only on the eastern side of the mosque is an external façade, fronted by an arcaded loggia from 1637.[14]: 39–40, 220 The adjoining rooms and structures around the rest of the mosque's perimeter include shops, libraries, and maqsuras (areas reserved for specific individuals or groups during prayer).[14]: 39–40 [6]

Courtyard and minaret

The courtyard is accessible from the exterior via seven doorways and is surrounded by galleries supported by arcades of arches and columns.[3] The gallery on the southern side, preceding the prayer hall, dates from the 10th-century Zirid restoration and is supported by spoliated antique columns and capitals,[3] while the three other galleries currently date from the 17th and 19th centuries,[6] with columns imported from Italy by the prime minister Mustapha Khaznadar in the mid-19th century.[3] The pavement of the courtyard itself consists of antique marble plaques, also spolia.[6]

The square minaret rises from the northwest corner of the courtyard. Built in 1894, the minaret is 43 meters (141 ft) high[12] and imitates the decoration of the Almohad minaret of the Kasbah Mosque with its limestone strap-work in a sebka pattern on a background of ochre sandstone.[3]

- Courtyard, minaret, and exterior details

- The exterior eastern façade of the mosque, with its 17th-century loggia

- Courtyard of the mosque, looking east, with the entrance to the prayer hall on the right

- Sundial and wells in the courtyard

- The present-day minaret (built in 1894)

Prayer hall

The central entrance to the prayer hall is covered by a dome, the Qubbat al-Bahu, added by the Zirids around 991.[14]: 86–87 Measuring about 12 metres in height and 4 metres in width,[citation needed] the dome has a sophisticated construction and Jonathan Bloom describes it is one of the finest architectural works from this period of western Islamic architecture.[14]: 86–87 The dome is ribbed and rests on an octagonal base, which rests in turn on a square supporting structure. The ornamentation includes carved moldings, decorative blind arches and niches, pilasters, and polychrome mosaic or ablaq stonework in red, white, and black stone. The arches and windows have horseshoe arches and voussoirs of alternating white and red stone.[14]: 87 [6] Arabic inscriptions in Fatimid floriated Kufic are found around the base of the dome and above the capitals of some of the columns.[6]

The hypostyle prayer hall is divided into 15 aisles by rows of columns, 6 bays long, supporting horseshoe arches running perpendicular to the southeastern qibla wall.[14]: 40–41 [3] Each aisle is about 3 metres wide but the central aisle, leading to the mihrab (niche symbolizing the qibla), is wider than the others at 4.8 metres.[3] Another transverse aisle runs in front of the qibla wall. There are around 160 columns and most of them are antique spolia, most likely taken from the site of Carthage.[14]: 40–41 [3] The space in front of the mihrab is covered by a well-preserved dome from the Aghlabid period (9th century), with Kufic inscriptions from the same period.[14]: 41 A few carved stucco panels along the upper walls of the central aisle, probably former windows, still date from the Aghlabid period.[10]

The mihrab itself was redecorated in later periods and most of the prayer hall's decoration, apart from the antique columns, dates from the 13th century onward.[14]: 41 [6] The stucco decoration around the mihrab dates largely from 1638, and the stuccowork on the imposts of the columns dates from 1820.[6] Inside the mihrab is a marble plaque covered in gold leaf and carved with an Aghlabid Kufic inscription with religious formulas such as the shahada.[6][10]

The minbar (pulpit) next to the mihrab is one of the oldest existing minbars after the minbar of Kairouan, though only some of its side panels are still originals from the Aghlabid period, with the others dating from later renovations. The latest pieces date from 1583 in the early Ottoman period. The minbar is smaller than the Kairouan minbar, measuring 2.53 by 3.30 metres. The wooden panels are carved with a variety of geometric and stylized vegetal motifs.[10]

- Prayer hall and interior details

- Bab al-Bahu, the central entrance to the prayer hall, and its dome (Qubbat al-Bahu)[6]

- Interior of the prayer hall

- View of the area around the mihrab

- The mihrab of the mosque

- Exterior view of the dome in front of the mihrab

See also

References

- ^ a b Ben Achour, M.A. (1991). Masjid al-Zaytūna: al-rijalu wa’l ma’lem [The Zaytuna Mosque: the men and the monument] (in Arabic). Tunis: Cérès Production.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Chater, Khalifa (2002). "Zaytūna". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Vol. XI. Brill. pp. 488–490. ISBN 9789004161214.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Ben Mami, Mohamed Béji. "Great Mosque of Zaytuna". Discover Islamic Art - Museum With No Frontiers. Archived from the original on 2020-06-12. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Al-Zaytuna Mosque through History". Al-Zaytuna Mosque. Archived from the original on 2010-01-27. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ^ "Al-Zaytuna Theological and Scientific Influence on the Islamic World". Al-Zaytuna Mosque. Archived from the original on 2010-05-12. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Lamine, Sihem (2018). "The Zaytuna: The Mosque of a Rebellious City". In Anderson, Glaire D.; Fenwick, Corisande; Rosser-Owen, Mariam (eds.). The Aghlabids and Their Neighbors: Art and Material Culture in Ninth-Century North Africa. Brill. pp. 269–293. ISBN 978-90-04-35566-8.

- ^ (in Italian) S. ROMANO. "Una santa palermitana venerata dai maomettani a Tunisi". Archivio storico siciliano, XXVI (1901), pp. 11–21.

- cfr. també F. SCORZA BARCELLONA. "Santi africani in Sicilia (e siciliani in Africa) secondo Francesco Lanzoni". Dins: Storia della Sicilia e tradizione agiografica nella tarda antichità. Atti del Convegno di Studi (Catania, 20–22 maggio 1986) Archived 2015-02-09 at archive.today, a cura de Salvatore Pricoco. Catanzaro 1988, pp. 37–55.

- ^ (in Italian) Daniele Ronco (2001). Il Maggio di Santa Oliva: Origine Della Forma, Sviluppo Della Tradizione Archived 2015-02-07 at the Wayback Machine. ETS, Pisa University, IT. 325 pages. pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b (in Italian) Sant' Oliva di Palermo Vergine e martire Archived 2023-06-04 at the Wayback Machine. SANTI, BEATI E TESTIMONI. 10 giugno. Retrieved: 02 February, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Daoulatli, Abdelaziz (2018). "La Grande Mosquée Zitouna : un authentique monument aghlabide (milieu du IXe siècle)". In Anderson, Glaire D.; Fenwick, Corisande; Rosser-Owen, Mariam (eds.). The Aghlabids and Their Neighbors: Art and Material Culture in Ninth-Century North Africa (in French). Brill. pp. 248–268. ISBN 978-90-04-35566-8.

- ^ a b Binous, Jamila; Baklouti, Naceur; Ben Tanfous, Aziza; Bouteraa, Kadri; Rammah, Mourad; Zouari, Ali (2010). "I.1.l The Great Mosque of Zituna". Ifriqiya: Thirteen Centuries of Art and Architecture in Tunisia (2nd ed.). Museum With No Frontiers, MWNF. ISBN 9783902782199.

- ^ a b "Jemaâ Ezzitouna". Municipality of Tunis. Archived from the original on 2009-05-26. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ^ Golvin, Lucien (1974). Essai sur l'architecture religieuse musulmane. Tome 3: L'architecture religieuse des "Grands ʻAbbâsides", la mosquée de Ibn Tûlûn, l'architecture religieuse des Aghlabides (in French). Klincksieck. p. 152., cited in Chater, Khalifa (2002). "Zaytūna". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Vol. XI. Brill. p. 488. ISBN 9789004161214.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700–1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300218701. Archived from the original on 2024-06-08. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Deeb, Mary-Jane (1995). "Zaytūnah". In Esposito, John L. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Modern Islamic World. Oxford University Press. pp. 374–375.

- ^ "Lieux de culte Municipalité de Tunis" (in French). Government of Tunis. Archived from the original on August 11, 2009. Retrieved July 23, 2010.

- ^ Charnay, Jean-Paul (January–February 1979). "Economy and Religion in the Works of Ibn Khaldun". The Maghreb Review. 4 #1: 1–25.

- ^ Abd el-Hafiz, Mansour (1969). Fihris Makhtutat el-Maktaba al- Ahmadiya bi Tunis. Beirut: Dar el-Fat'h. pp. 8–9.

- ^ Sibai, M. (1987). Mosque Libraries : An Historical Study. London and New York: Mansell Publishing Limited. p. 98.

- ^ a b "Tunis reopens ancient Islamic college to counter radicals". Reuters. 2012-04-04. Archived from the original on 2022-11-03. Retrieved 2022-11-03.

- ^ a b Feuer, Sarah (2016). State Islam in the Battle against extremism: Emerging Trends in Morocco & Tunisia. The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Archived from the original on 2022-11-03. Retrieved 2022-11-03.

- ^ "Controversy Surrounding the Al-Zaytuna Mosque in Tunis: The Ambivalent Revival of Islamic Traditions - Qantara.de". Qantara.de - Dialogue with the Islamic World. Archived from the original on 2022-11-03. Retrieved 2022-11-03.

![Bab al-Bahu, the central entrance to the prayer hall, and its dome (Qubbat al-Bahu)[6]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a1/L%27entr%C3%A9e_principale_du_Grande_mosqu%C3%A9e_d%27Ezzitouna.jpg/100px-L%27entr%C3%A9e_principale_du_Grande_mosqu%C3%A9e_d%27Ezzitouna.jpg)