Georgy Pyatakov

Georgy Pyatakov | |

|---|---|

| Георгий Пятаков | |

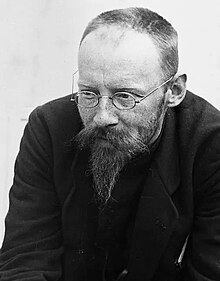

Pyatakov in 1922 | |

| Chairman of the Ukrainian Provisional Government | |

| In office November 28, 1918 – January 29, 1919 | |

| President | Hryhoriy Petrovsky (chairman of VUTsVK) |

| Preceded by | Office Established |

| Succeeded by | Christian Rakovsky |

| Secretary of Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine | |

| In office March 6, 1919 – May 30, 1919 | |

| Preceded by | Emmanuel Kviring |

| Succeeded by | Stanislav Kosior |

| In office July 12, 1918 – September 9, 1918 | |

| Preceded by | Office Established |

| Succeeded by | Serafima Hopner |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 18, 1890 Horodyshche, Cherkassky Uyezd, Kiev Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | January 30, 1937 (aged 46) Moscow, Soviet Union |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Political party | RSDLP (Bolsheviks) (1910–1918) Russian Communist Party (1918–1927, 1928–1936) |

| Spouse | Yevgenia Bosch |

| Alma mater | Saint Petersburg University |

| Occupation | Politician/Statesman |

Georgy (Yury) Leonidovich Pyatakov (Russian: Георгий Леонидович Пятаков; 6 August 1890 – 30 January 1937) was a Ukrainian revolutionary and Bolshevik leader, and a key Soviet politician during and after the 1917 Russian Revolution. Pyatakov was considered by contemporaries to be one of the early communist state's best economic administrators, but with poor political judgement.

Biography

Early life and pre-revolution

Pyatakov (party pseudonyms: Kievsky, Lyalin, Petro, Yaponets (Japanese), Ryjii) was born 6 August 1890 in the Cherkasy district in the Kiev Governorate of the Russian Empire, now modern-day Ukraine, where his father, Leonid Timofeyevich Pyatakov (1847–1915), was an engineer and director of the large Mariinsky or Horodyshche Sugar Refinery.[1] Leonid Pyatakov was also the co-owner of Musatov, Pyatakov, Sirotin, and Co.[citation needed]

Pyatakov first became politically active at the age of 14 in secondary school in Kiev. During the 1905 revolution, he was expelled for leading a 'school revolution', and joined an anarchist group, which carried out armed robberies. In 1907 he was involved in a plot to assassinate the Governor General of Kiev, Vladimir Sukhomlinov,[1] but broke with anarchism that same year and began to study Marxism, particularly the writings of Georgi Plekhanov and Vladimir Lenin.

From 1907, he was a student at the Faculty of Economics of St Petersburg University, until he was expelled in 1910, and deported back to Kiev, for taking part in student disturbances. There, he joined the Bolshevik wing of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. Arrested in June 1912, he spent a year and a half exiled to Siberia with his partner, Yevgenia Bosch, in the village of Usolye, Irkutsk.

In October 1914, he and Bosch escaped from exile through Japan and the United States to Switzerland, where they joined the émigré revolutionary community, and joined the editorial board of the journal Kommunist. However, during 1915, the Bolshevik group in Switzerland was split over the issue of small nations' rights to national self-determination, which Lenin supported, but Nikolai Bukharin, Pyatakov, and Bosch opposed. On 30 November 1916, Lenin wrote to his confidant Inessa Armand, complaining that "neither Yuri (Pyatakov), quite a little pig, nor E. B. has a particle of brain, and if they had allowed themselves to descend to group stupidity with Bukharin, then we had to break with them, more precisely with Kommunist. And that was done."[2]

After this breach, Pyatakov, Bukharin, and Bosch moved to Stockholm, but were expelled from Sweden in April 1916 for being present at a conference organised by Swedish socialists to oppose attempts to involve Sweden in World War I. They moved to Oslo, Norway (then called Kristiania), where they lived in "extreme poverty".[3]

Pyatakov and Bosch remained together until she committed suicide by self-inflicted gunshot in January 1925, after hearing that Trotsky had been forced to resign as leader of the Red Army, as well as in pain from her heart condition and tuberculosis.

Revolution and Civil War

After the February Revolution, Pyatakov returned to Russia from Norway but was arrested at the border due to having a false passport. He was subsequently escorted to Petrograd, and then finally to Kiev.[1] He lived in Ukraine from March 1917, becoming a member, then in April, chairman, of the Kiev Committee of the RSDLP. He was elected a vowel of the Kiev City Duma on 5 August 1917.

For the next ten years, Pyatakov was a leader of the left-wing communists. His opinions on some points of the theory and tactics of the revolutionary struggle were in opposition to that of the party's Central Committee. He was one of Vladimir Lenin's fiercest opponents on the national problem regarding both the course to be followed towards the socialist revolution as well as the Bolsheviks' peace settlement with Germany. After Lenin died in 1924, Pyatakov campaigned to prevent the rise of Joseph Stalin.

During the party conference in Petrograd, in May 1917–at a time of growing support in Finland for independence from Russia– Stalin put forward a motion in favour of self-determination of small nations, which Pyatakov opposed. He declared that the party had to end the idea of self-identification of every nation, and stood for anti-chauvinistic international principles;[4][5] he proposed that the party adopt the slogan "down with frontiers", which Lenin dismissed as "hopelessly muddled" and a "mess".[6]

After the October Revolution, in November 1917, Lenin called Pyatakov to Petrograd to take over the state bank, whose staff were refusing to release funds for the new government.

In January 1918, Pyatakov was one of the leaders of the Left Communists, who opposed Lenin's decision to end the war with Germany through the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (signed 3 March 1918). In protest, he resigned his post at the state bank and returned to Ukraine, intending to organise partisan warfare against the advancing Imperial German Army.[1]

At the founding congress of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Ukraine, in Taganrog in July 1918, Pyatakov was elected as Central Committee Secretary. He maintained that Ukraine was not a signatory to the Brest-Litovsk treaty, and could therefore justifiably go to war against Germany. He and his supporters on the left, who included Bosch and Andrei Bubnov, remained in control of the Ukrainian party during most of 1918, but the insurrection which they launched against the pro-German Hetman, Pavlo Skoropadskyi, failed.[7]

From November 1918, after the German army withdrew from Ukraine, to mid-January 1919, Pyatakov was a head of the Provisional Worker's and Peasant's Government of Ukraine (Russian: Временное рабоче-крестьянское правительство Украины). In January 1919 Lenin replaced Pyatakov as head of the Ukrainian government with Christian Rakovsky

In March 1919, while attending the 8th Congress of the Russian Communist Party, Pyatakov again unsuccessfully opposed Lenin's position on national self-determination, which he denounced as a 'bourgeois' slogan that "unites all counter-revolutionary forces."[8]

Pyatakov collaborated with Nikolai Bukharin to co-author the chapter on "The Economic Categories of Capitalism in the Transition Period" in The Economics of the Transformation Period, published in 1920.[9]

Pyatakov served as a political commissar with the Red Army in Ukraine during the Russian Civil War, and again during the 1920 Polish–Soviet War. From 1 January to 16 February 1920, he led the Registration Directorate, the Red Army's military intelligence arm that went on to become the GRU.

Post-Civil War

From the end of the civil war, in 1920, until 1936, Pyatakov worked as an economic administrator, with short interruptions. From 1920-1921, he was placed in charge of the management of the coal mining industry in the Donbas. In February 1921, he was appointed deputy chairman of the Gosplan (State Planning Committee) of the RSFSR. From 1923–1926, he was deputy Chairman of the Supreme Council of the National Economy of the Soviet Union.

From June–August 1922, Pyatakov was chairman of the panel of judges during the Trial of the Socialist Revolutionaries. At the conclusion of which, he sentenced all 12 defendants to death- though the death sentences were later commuted.

In October 1923, travelling under the name 'Arwid', Pyatakov was part of the Comintern sent to Germany during the abortive attempt to bring about a communist revolution.[10]

Pyatakov was one of only six leading Bolsheviks mentioned in Lenin's Testament, dictated in December 1922, during Lenin's terminal illness. The other five-Stalin, Trotsky, Grigory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, and Bukharin- were all members of the Politburo, while Pyatakov was not even one of the 27 full members of the Central Committee, to which he had been elected a candidate member, for the first time, in April 1922.[11] He became a full member only in May 1924. Lenin described Pyatakov as "a man undoubtedly distinguished in will and ability, but too much given over to administration and the administrative side of things to be relied on in a serious political situation."[12]

Pyatakov supported Leon Trotsky in the power struggle that began during Lenin's terminal illness. He was a signatory of The Declaration of 46 in October 1923, and in the debate that followed he was "their most aggressive and effective spokesman" who "wherever he went easily obtained large majorities for bluntly worded resolutions."[13] But his personal relationship with Trotsky was distant. Simon Liberman, who worked for the Soviet government during part on the 1920s was with Pyatakov in the Crimea, in 1920, and witnessed how he reacted when Trotsky rang:

As he picked up the telephone leisurely and listened, Pyatakov's whole manner changed. It became quick and nervously abrupt. He said, "Right away!" and after replacing the receiver began hurriedly to put on his military equipment – all of it, it seemed. Tightening his belt sprucely, fastening his sabre and his holstered revolver, he explained without looking at me: "Lev Davidovich loves the 'pathos of distance' between us and himself. He is probably right."[14]

Despite his support for Trotsky, Pyatakov was anxious that the communist party did not split irreconcilably. After an angry meeting in October 1926, at which Trotsky called Stalin the 'gravedigger of the revolution' to his face, Pyatakov was visibly distressed and demanded of Trotsky "Why, why have you said this?", but Trotsky simply brushed him aside.[15]

In 1927, Pyatakov was sent to Paris as trade representative at the USSR embassy. In December 1927, he was expelled from the Communist Party for belonging to the "Trotskyite–Zinovievite" bloc. He was the first "Trotskyist" to renounce Trotskyism. His capitulation was reported in Pravda on 29 February 1928. For the next eight years he stuck to the party line. This prompted a scathing comment from Trotsky:

When Pyatakov belonged to the same group as I did, I prophesied in jest that in the event of a Bonapartist coup d'état, Pyatakov would go to the office the next day with his brief case. Now I can add more earnestly that if this fails to come about, it will be only through lack of a Bonapartist coup d'état, and not through any fault of Pyatakov's.[16]

When the former Menshevik, Nikolai Valentinov met Pyatakov in Paris early in 1928 and suggested to him that he has capitulated out of cowardice, Pyatakov riposted with a eulogy about the historic role of the Soviet communist party saying that, for the party, nothing was inadmissible, and nothing impossible, and that a true Bolshevik submerged his personality in the party to the extent that he could break with his own beliefs and honestly agree with the party. [17]

Pyatakov was recalled to Moscow and restored to party membership in 1928. He was deputy chairman of Gosbank in 1928–29, and chairman, 1929–30.[18][19] After Stalin had ordered the start of the campaign to force peasant farmers to move on to collective farms, Pyatakov gave a speech in October 1929 calling for "extreme rates of collectivisation" and declaring that "the heroic period of our socialist construction has begun."[20]

But in August 1930, Stalin complained in a letter to the head of the soviet government, Vyacheslav Molotov that Pyatakov was a "poor commissar" and a "hostage to his bureaucracy". In September, he called him a "genuine rightist Trotskyist" and a "harmful element". Pyatakov was removed from office on 15 October, and appointed head of the All-Union Chemical Industry Association.[21]

In 1932, when the Supreme Economic Council was broken up, and part of it became the People's Commissariat of Heavy Industry of the USSR, Pyatakov was appointed deputy People's Commissar, under Sergo Ordzhonikidze. In February 1934, he was restored to full membership of the Central Committee. In October 1935, he chaired the first congress of Stakhanovite workers.

Arrest and execution

Pyatakov's wife was arrested July 1936, during the preliminary stage of the Great Purge. He was in Kislovodsk at the time, but returned to Moscow, and met Stalin and other senior communists, who told him that several former members of the Left Opposition being held by the NKVD had confessed to being part of an anti-soviet conspiracy, and had implicated Pyatakov. He insisted that they were lying. According to what Stalin told a Central Committee plenum six months later, Pyatakov was invited to act as public prosecutor in the forthcoming show trial, to which he readily agreed, but, according to Stalin, when told that he would not be suited to the task, he exclaimed: "How can I prove that I am right? Let me! I will personally shoot all those you condemn to be shot. All the bastards!"[22]

This has been taken to imply that Pyatakov was volunteering to shoot his wife, the mother of his children, if she were convicted and condemned to death.[23]

Pyatakov was allowed to put his name to an article that appeared in Pravda on 21 August 1936, halfway through the first of the Moscow show trials, in which Zinoviev and Kamenev were lead defendants, declaring: "These people have lost the last semblance of humanity. They must be destroyed like carrion polluting the pure bracing air of the lands of the soviets...",[24] but that evening the prosecutor Andrey Vyshinsky publicly announced that Pyatakov, among others, had been named by the defendants as being involved in 'criminal counter-revolutionary activities, and was under investigation.[25] On 11 September 1936, the Politburo ruled that he was to be expelled from the Central Committee and from the party.[26]

On 12 September 1936, Pyatakov was arrested in his service car at the San-Donato station in Nizhny Tagil. From 23–30 January 1937, he was the lead defendant at the second of the Moscow show trials, the trial of the so-called 'Anti-Soviet Trotskyite Centre', a 'parallel' centre that was supposedly run from abroad by Trotsky with the intention of overthrowing the Soviet government.

At his trial he was accused of conspiring with Trotsky in connection with the case of a so-called Parallel anti-Soviet Party Centre to overthrow the Soviet government in collaboration with Nazi Germany, the latter being promised a reward of large tracts of Soviet territory, including Ukraine. On the opening day of the trial Pyatakov told a story that while he was on an official visit to Berlin in December 1935, he secretly flew by private plane to an airdrome 'in Oslo' where he was taken by car to meet Trotsky, who was in exile in Norway, to receive instructions.[27] This was provably false. Within a few days, Norwegian journalists had established that no aircraft had landed at Oslo's Kjeller airfield in December 1935, nor on any date between September and May.[28] On 30 January 1937, he was sentenced to death, and executed on 1 February.[29]

Pyatakov was posthumously rehabilitated and reinstated in the party on 13 June 1988 by a decision taken under the leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev.[30]

Family

Pyatakov's older brother, Leonid (1888–1917) joined the Bolsheviks in 1916, and in 1917 was elected chairman of the Kiev revolutionary committee. He stayed in Kiev while it was ruled by the Central Rada. He was arrested by Cossacks on 25 December 1917, and was found dead near Kiev on 15 January, his body showing marks of torture. The Rada denied ordering his killing.[31]

Their older brother, Mikhail, (1886–1958) joined the Constitutional Democratic Party before the Bolshevik revolution. Afterwards, he worked as a scientist. He was arrested three times: in Vladivostok, in 1931; and sentenced to three years' exile; in Baku, in 1939, and sentenced to eight years in labour camps; and in 1948, in Aralsk. He died in Baku.[32]

Their younger brother, Ivan (1893–1937), who worked as an agronomist in Vinnytsia, was shot in 1937.[33]

Their sister, Vera, (1897–1938), who worked as a biologist, was arrested in 1937, and shot.[34]

Pyatakov's second wife, Ludmila Dityateva (1899-1937),[35] whom he married during the civil war, joined the communist party in 1919, was expelled in 1927 as a member of the Left Opposition, and reinstated in 1929. On 11 June 1936, she was appointed the first woman director of the Krasnopresnenskaya Thermal Power Plant in Moscow, less than two months later, on 11 July.[35] She was shot on 20 June 1937. She was 'rehabilitated' at the same time as Pyatakov in 1991.[36]

They had three children. Their son, Grigori, born in 1919, changed his name to Proletarsky to avoid being persecuted because of his parents. He died in 2011. Their daughter, Rada, (1923-1942), was sent to an orphanage in 1937 and died during the Siege of Leningrad. Their youngest, Yuri, born 1929, was also sent to an orphanage. His fate is unknown.[36]

References

- ^ a b c d Georges Haupt, and Jean-Jaques Marie (1974). Makers of the Russian Revolution. (This volume includes a translation of an autobiographical entry written by Pyatakov around 1926, for a Soviet encyclopaedia) London: George Allen & Unwin. pp. 182–4. ISBN 0-04-947021-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Lenin, V.I. (1976). Collected Works, volume 35. Moscow: Progress Publishers. pp. 250–55. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- ^ Futrell, Michael (1963). Northern Underground, Episodes of Russian Revolutionary Transport and Communications through Scandinavia and Finland, 1863–1917. London: Faber and Faber. p. 126,131.

- ^ Subtelny, Orest. "History of Ukraine". uahistory2006.narod.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- ^ "Пятаков, Георгий Леонидович". www.hrono.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- ^ Lenin, V.I. Collected Works, volume 24 (PDF). pp. 299–300. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ^ Daniels, Robert Vincent (1969). The Conscience of the Revolution, Communist Opposition in Soviet Russia. Simon & Schuster. pp. 98–99.

With a majority behind them during the spring and summer of 1918, the Ukrainian Left Communists went ahead with their plans for an insurrection, but the attempt, launched in August 1918, was a complete fiasco.

- ^ Carr, E.H. (1969). The Bolshevik Revolution, 1917–1923 volume 1. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin. p. 274.

- ^ Bukharin, Nikolai; Field, Oliver (1979). The Politics and Economics of the Transition Period (PDF). Routledge, Kegan and Paul. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ Branko Lazitch, in collaboration with Milorad M.Drachkovitch (1973). Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern. Stanford CA: Hoover Institution Press. p. 311. ISBN 0-8179-1211-8.

- ^ Schapiro, Leonard (1965). The Origin of the Communist Autocracy, Political Opposition in the Soviet State: First Phase, 1917–1922. New York: Frederick A. Praeger. p. 368.

- ^ Carr, E.H. (1969). The Interregnum 1923–1924. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin. p. 267.

- ^ Deutscher, Isaac (1989). The Prophet Unarmed, Trotsky 1921–1929. Oxford U.P. p. 116. ISBN 0-19-281065-0.

- ^ Liberman, Simon (1945). Building Lenin's Russia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 73.

- ^ Deutscher. The Prophet Unarmed. p. 297.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (1975). My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin. p. 456.

- ^ Schapiro, Leonard (1970). The Communist Party of the Soviet Union. London: Methuen. p. 385.

- ^ "Пятаков, Георгий Леонидович 1890–1937". Khronos. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ "The State Bank of the USSR". Bank of Russia Today. Bank of Russia. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ Davies, R.W. (1980). The Industrialisation of Soviet Russia 1: The Collectivsation of Soviet Agriculture, 1929–1930. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard U.P. p. 148. ISBN 0-674-81480-0.

- ^ Lars T. Lih (1995). Oleg V.Naumov; Oleg V.Khlevniuk (eds.). Stalin's Letters to Molotov. New Haven: Yale U.P. pp. 204, 211, 214. ISBN 0-300-06211-7.

- ^ M. Svitlana, and A. Erdogan. Transcripts from Soviet Archives, volume III. San Francisco: Academia.edu. pp. 109–10.

- ^ e.g.Rayfield, Donald (2004). Stalin and his Hangmen. New York: Random House. p. 271 ("Such evil idiocies reached their nadir when in 1936 Georgy Pyatakov begged Nikolai Yezhov to let him shoot his convicted wife"). ISBN 0-375-50632-2.

- ^ Conquest, Robert (1971). The Great Terror, Stalin's Purge of the Thirties. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin. pp. 162–63.

- ^ Report of Court Proceedings, The Case of the Trotskyite-Zinovievite Terrorist Centre. Moscow: People's Commissariat of Justice of the USSR. 1936. p. 115.

- ^ J.Arch Getty, and Oleg V.Naumov (1999). The Road to Terror, Stalin and the Self-Destruction of the Bolsheviks, 1932–1939. New Haven: Yale U.P. p. 286. ISBN 0-300-07772-6.

- ^ Report of Court Proceedings in the Case of the Anti-Soviet Trotskyite Centre. Moscow: People's Commissariat of Justice of the USSR. 1937. pp. 59–60.

- ^ Conquest. The Great Terror. p. 237.

- ^ "Пятаков Юрий Леонидович (1890)". Открыты Список (Open List). Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ "Пятаков Юрий Леонидович – Мартиролог: Жертвы политических репрессий, расстрелянные и захороненные в Москве и Московской области в период с 1918 по 1953 год". www.sakharov-center.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- ^ Shchus, O. M. "Пятаков Леонид Леонидович 1888–1917". Khronos. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ "Пятаков Михаил Леонидович (1886)". Открыты Список (Open List). Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ "Пятаков Иван Леонидович (1893)". Открыты Список. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ "Пятакова Вера Леонидовна (1897)". Открыты Список. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ a b Andreyev, L.G. "Людмила Федоровна Дитятева – первая женщина директор Московской ТЭЦ". Музей истории Мосэнерго. Mosenergo Museum. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Дитятева Людмила Федоровна (1899)". Открыты Список. Retrieved 22 May 2023.