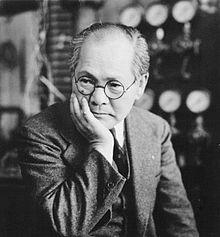

Yoshio Nishina

Yoshio Nishina | |

|---|---|

仁科 芳雄 | |

| |

| Born | December 6, 1890 |

| Died | January 10, 1951 (aged 60) |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Alma mater | Tokyo Imperial University |

| Known for | Klein–Nishina formula |

| Awards | Asahi Prize (1944) Order of Culture (1946) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | RIKEN |

| Notable students | Hideki Yukawa Sin-Itiro Tomonaga Shoichi Sakata |

Yoshio Nishina (仁科 芳雄, Nishina Yoshio, December 6, 1890 – January 10, 1951) was a Japanese physicist who was called "the founding father of modern physics research in Japan". He led the efforts of Japan to develop an atomic bomb during World War II.[1]

Early life and career

Nishina was born in Satoshō, Okayama. He received a silver watch from the emperor as he graduated at the top of his class at Tokyo Imperial University as an electrical engineer in 1918.[2] He became a staff member at the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research (now RIKEN) where he began studying physics under Hantaro Nagaoka.

In 1921, he was sent to Europe for research. He visited some European universities and institutions, including Cavendish Laboratory, Georg August University of Göttingen, and University of Copenhagen. In Copenhagen, he did research with Niels Bohr, and they became good friends. In 1928, he wrote a paper on incoherent or Compton scattering with Oskar Klein in Copenhagen, from which the Klein–Nishina formula derives.[3]

In 1929, he returned to Japan, where he endeavored to foster an environment for the study of quantum mechanics. He established Nishina Laboratory at RIKEN in 1931, and invited some Western scholars to Japan including Heisenberg, Dirac and Bohr to stimulate Japanese physicists. It was also in 1931 that he lectured about the Dirac theory in Kyoto, which was where he met and was attended by Hideki Yukawa and Sin-Itiro Tomonaga.[4]

Atomic bomb

On 7 August 1945, Nishina led a team of scientists sent by the Japanese high command to confirm whether or not Hiroshima was attacked with an atomic bomb. After making the physical measurements necessary to confirm the bomb's nature, he wired his confirmation of an atomic bomb back to Tokyo on August 8.[5]

His laboratory was severely damaged during World War II, and most of its equipment had to be discarded and rebuilt after the war.[6]

Postwar

The US Army occupation forces dismantled his cyclotrons on 22 November 1945, and parts were dumped into Tokyo Bay. The aftermath of the incident caused a huge furor in the US.[7] Nishina later published an article on his reaction to the cyclotron's destruction.[8]

The American physicists Harry C. Kelly and Gerald Fox were recruited to the occupation forces. Fox stayed a few months in Japan, but Kelly stayed until 1950 and became friends with Nishina, who spoke English. At one point, the US Army formulated a list of Japanese scientists to purge, which included Nishina's name. Asked to vet Nishina by US intelligence officers, Kelly took the file home and made his assessment: “He was an international scholar, respected all over the world. And he had spoken out against the war. I said it was against everyone's interests to purge that man."[9] Nishina sought to restart Japanese science after the war and found an ally in Kelly. Two issues were most important for Nishina: acquiring radio isotopes for research for a variety of nonmilitary purposes and attempting to preserve Riken as an institution for scientific research, which occupation forces were seeking to dismantle on the basis of anti-monopoly concerns. Riken owned stocks of some large companies. When an interim agreement was worked out, Nishina became head of the reorganized Riken.[10]

Nishina died from liver cancer in 1951.[3] Since Nishina's widow was ailing herself, help with care of Nishina's children (Yuichiro and Kojiro) came from Nishina's assistant at Riken, Sumi Yokoyama. Harry Kelly, his friend and colleague, remained close to the family after Nishina's death.

Kelly's ashes were buried in a grave besides Nishina's in Tama Cemetery in Tokyo in a ceremony attended by Nishina's and Kelly's families.[11]

Work

Nishina co-authored the Klein–Nishina formula. His research was concerned with cosmic rays and particle accelerator development for which he constructed a few cyclotrons at RIKEN. In particular, he detected what turned out to be the muon in cosmic rays, independently of Anderson et al.[3] He also discovered the uranium-237 isotope and pioneered the studies of symmetric fission phenomena occurring upon fast neutron irradiation of uranium (1939–1940), and narrowly missed out on the discovery of the first transuranic element, neptunium.[12]

He was a principal investigator of RIKEN and mentored generations of physicists, including two Nobel Laureates: Hideki Yukawa and Sin-Itiro Tomonaga. During World War II, he was the head of the Japanese nuclear weapon program.

See also

- Nishina Memorial Prize

- Nishina, a crater on the Moon named in Nishina's honor.

References

- ^ "Yoshio Nishina". Atomic Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 2017-12-03.

- ^ "Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences: HSPS". 2004.

- ^ a b c Sin-Itiro Tomonaga Yoshio Nishina, His Sixtieth Birthday Archived March 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, November 20, 1950 (updated January 11, 1951)

- ^ p.94 of "Quantum revolution: Qed: the jewel of physics", Volume 2 by G. Venkataraman

- ^ p.235 of "Radioactivity: Introduction and History, From the Quantum to Quarks" by Michael F. L'Annunziata

- ^ Yoshio Nishina – Father of Modern Physics in Japan. Nishina Foundation

- ^ Yoshikawa, Hideo and Joanne Kauffman, Science Has No National Boundaries: Harry C. Kelly and the Reconstruction of Science and Technology in Postwar Japan. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press 1994, pp 6-9.

- ^ Nishina, Yoshio (June 1947). "A Japanese Scientist Describes the Destruction of his Cyclotron". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 3 (6): 145, 167. Bibcode:1947BuAtS...3f.145N. doi:10.1080/00963402.1947.11455874.

- ^ quoted in Boffey, Philip M. “Harry C. Kelly: An Extraordinary Ambassador to Japanese Science.” Science. New Series, vol. 169, no. 3944 (July 31, 1970) p. 451.

- ^ Yoshikawa and Kauffman, pp. 79, 88-91.

- ^ Yoshikawa and Kauffman,Science Has No National Boundaries,pp. 92-93, 105.

- ^ Ikeda, Nagao (25 July 2011). "The discoveries of uranium 237 and symmetric fission — From the archival papers of Nishina and Kimura". Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B: Physical and Biological Sciences. 87 (7): 371–6. Bibcode:2011PJAB...87..371I. doi:10.2183/pjab.87.371. PMC 3171289. PMID 21785255.