Yellowfin madtom

| Yellowfin madtom | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Siluriformes |

| Family: | Ictaluridae |

| Genus: | Noturus |

| Species: | N. flavipinnis |

| Binomial name | |

| Noturus flavipinnis W. R. Taylor, 1969 | |

The yellowfin madtom (Noturus flavipinnis) is a species of fish in the family Ictaluridae endemic to the southeastern United States. Historically, the yellowfin madtom was widespread throughout the upper Tennessee River drainage but was thought to be extinct by the time it was formally described.[4]

Distribution

The yellowfin madtom is largely found in Citico Creek of Monroe County, Tennessee, and reintroduced into Abrams Creek within the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Prior to 1893, N. flavipinnis is thought to have been present throughout the upper Tennessee River drainage system. The species was thought to be extinct when it was described in 1969, 30 years after the Norris Dam on the Clinch River became operational.[5] Since then, populations of the yellowfin madtom have been found in Copper Creek and the Clinch River in Virginia, the Powell River and Citico Creek in Tennessee, and a few populations have also been found in streams of northern Georgia, though the yellowfin madtom is now listed as extirpated in Georgia.[6][7]

Ecology

The yellowfin madtom is nocturnal and an opportunistic feeder. It preys on aquatic invertebrates, small fish, and detritus.[8] During the daytime, the yellowfin madtom often hides in brushpiles or bedrock crevices and can even bury itself under several inches of gravel.[5] N. flavipinnis is able to survive in a wide range of environments, from small, pristine, silt-free waters in Citico Creek to the larger, warm, and very silty Powell River.[6]

While no specific predator is known, the yellowfin madtom exhibits cryptic coloration and also hides itself in the daytime, both of which are predator-avoidance strategies. The yellowfin madtom is nocturnal animal and has been known not to try to escape captivity.[9] Generally, it inhabits pools and backwaters of streams no more than 2.0 m deep.[9] The water usually has a moderate current and is siltless, which allows the fish to bury itself into the gravel and bedrock.[6]

The closely related N. baileyi is thought to be one of N. flavipinnis’s biggest competitors, though due to the building of a small dam in 1973, interactions between the two have lessened considerably. Both catfish are small and are present in the same river systems, with declining populations. The separation of the yellowfin madtom from its biggest competitor seems to have had negative effects on its populations, as they start to compete among themselves.

The yellowfin madtom has a relatively short lifespan. Generally, it lives up to four years and is most often found in the pools and streams in which they were born. Their breeding season begins in late May and continues through late July. The males are able to mate once during the breeding season and build and guard the nests containing between 30 and 100 eggs. Females, though, are able to reproduce twice in one breeding season and produce 121–278 eggs per season, with an average of 89 hatching. Hatching usually takes eight days, and the male guards the eggs and hatchlings for two weeks. N.flavipinnis reaches sexual maturity at two years of and usually lives through two breeding seasons. Often, they use backwater pools and streams that are as clean and siltless as possible to breed and bury their eggs beneath rocks.[10]

Management

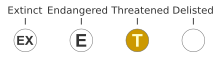

The yellowfin madtom is federally listed as a threatened species and as endangered in both Tennessee and Virginia. Agricultural practices around the shallow creeks and streams where N. flavipinnis resides have decreased the population and made it difficult for them to recover. Efforts to increase their population began in 1986 at the University of Tennessee and later moved to Conservation Fisheries, Inc. (CFI) in Knoxville. Since the population was too low to take individuals away from Citico Creek, eggs were taken from nests and reared in aquatic laboratories at CFI. CFI was also allowed to maintain a captive adult population to breed inside their aquatic laboratories.

From 1986 until 2003, two to three yellowfin madtom clutches were taken from Citico Creek for captive propagation to be stocked into Abrams Creek. The captured fish were released into both Abrams Creek and Citico Creek irregularly to try to restore a population and save a population, respectively. The yellowfin madtom has had a 53% survival rate among its captured egg clutches, and new fish have been found in Abrams Creek almost every year since 1994. In 2003, though only 9 yellowfin madtom were found in Abrams Creek, they were believed to be wild-spawned, since tagged fish had not been released since 2001, marking what looks to have been a successful project in restoring them in Abrams Creek.

To help the restoration project in Abrams Creek, the National Park Service, US Forest Service, University of Tennessee, and Tennessee Valley Authority have taken up the duty to improve the water and habitat of Abrams Creek. The groups helped to remove cattle and restore riparian vegetation around Abrams Creek and its tributaries. The hope is that the restoration of the Abrams Creek habitat decreases its silt content which has been proven to be the yellowfin madtom's worst enemy.[11]

Since 1986, populations of the yellowfin madtom from Citico Creek have been captured and bred in laboratory to be reintroduced into Abrams Creek in Blount County, Tennessee, which in 1957 had half of its 64 species extirpated by ichthyocides with the intention to increase trout fishery. From 1986 until 2003, the population of the yellowfin madtom in Abrams Creek has increased to 1,574. Currently, they are no longer stocked and released into Abrams Creek.[11]

References

- ^ NatureServe (2013). "Noturus flavipinnis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T14900A19033751. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T14900A19033751.en. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Yellowfin madtom (Noturus flavipinnis)". Environmental Conservation Online System. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ^ 42 FR 45526

- ^ Taylor, W. R. 1969. A revision of the catfish genus Noturus Rafinesque with an analysis of higher groups in the Ictaluridae. Bull. U. S. Nat. Mus. 282:1–315.

- ^ a b Etnier, David A. and Wayne C. Starnes. 1993. The Fishes of Tennessee. University of Tennessee Press. Knoxville, Tennessee.

- ^ a b c Shute, P. W. 1984. Ecology of the rare yellowfin madtom, Noturus flavipinnis Taylor, in Citico Creek, Tennessee. M. S. Thesis, Univ. Tenn.

- ^ Dinkins Gerald R. and P. Shute. 1996. Life histories of Noturus baileyi and N. flavipinnis (Pisces: Ictaluridae), two rare madtom catfishes in Citico Creek, Monroe County, Tennessee. Bulletin Alabama Museum of Natural History 18: 43–69.

- ^ Stegman, J. L. and W. L. Minckley. 1959. Occurrence of three species of fishes in interstices of gravel in an area of subsurface flow. Copeia 1959:341.

- ^ a b Bauer B.H., G. Dinkins and D. Etnier.1983. Discovery of Noturus-baileyi and Noturus-flavipinnis in Citico Creek, Little Tennessee River System. Copeia 2:558–560.

- ^ Virginia Tech Fish and Wildlife Information Exchange, 1996. "Madtom and Yellowfin" (On-line). Endangered Species Information System.

- ^ a b Shute J.R. and P. Rakes, P. Shute. 2005. Reproduction of four imperiled fishes in Abrams Creek, Tennessee. Southeastern Naturalist 4: 93–110.

Further reading

- Legrande W.H. 1981. Chromosomal evolution in North American catfishes (Siluriformes, Ictaluridae) with particular emphasis on the madtoms, Noturus. Copeia 1981(1):33–52. doi:10.2307/1444039 JSTOR 1444039

- Shute P.W, Rakes P.L, Shute J.R. and Tullock J.H. 1991. A second chance for two native catfish species. Freshwater and Marine Aquarium 14: 92–94, 180.

- Virginia Tech Fish and Wildlife Information Exchange, 1996. "Madtom, Yellowfin" (On-line). Endangered Species Information System. http://fwie.fw.vt.edu/WWW/esis/lists/e254002.htm. Archived 3 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine