Wolof language

| Wolof | |

|---|---|

| Wolof làkk, وࣷلࣷفْ لࣵکّ | |

| Native to | Senegal, Gambia, Mauritania |

| Region | Senegambia |

| Ethnicity | Wolof |

| Speakers | L1: 7.1 million (2013–2021)[1] L2: 16 million (2021)[1] |

| Dialects |

|

| Latin (Wolof alphabet) Arabic (Wolofal) Garay | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Senegal |

| Regulated by | CLAD (Centre de linguistique appliquée de Dakar) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | wo |

| ISO 639-2 | wol |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:wol – Wolofwof – Gambian Wolof |

| Glottolog | wolo1247 |

| Linguasphere | 90-AAA-aa |

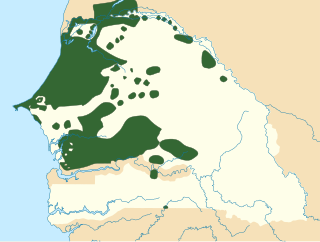

Areas where Wolof is spoken | |

Wolof (/ˈwoʊlɒf/ WOH-lof;[2] Wolof làkk, وࣷلࣷفْ لࣵکّ) is a Niger–Congo language spoken by the Wolof people in much of the West African subregion of Senegambia that is split between the countries of Senegal, The Gambia and Mauritania. Like the neighbouring languages Serer and Fula, it belongs to the Senegambian branch of the Niger–Congo language family. Unlike most other languages of its family, Wolof is not a tonal language.

Wolof is the most widely spoken language in Senegal, spoken natively by the Wolof people (40% of the population) but also by most other Senegalese as a second language.[3] Wolof dialects vary geographically and between rural and urban areas. The principal dialect of Dakar, for instance, is an urban mixture of Wolof, French, and Arabic.

Wolof is the standard spelling and may also refer to the Wolof ethnicity or culture. Variants include the older French Ouolof, Jollof, or Jolof, which now typically refers either to the Jolof Empire or to jollof rice, a common West African rice dish. Now-archaic forms include Volof and Olof.

English is believed to have adopted some Wolof loanwords, such as banana, via Spanish or Portuguese,[4] and nyam, used also in Spanish: 'ñam' as an onomatopoeia for eating or chewing, in several Caribbean English Creoles meaning "to eat" (compare Seychellois Creole nyanmnyanm, also meaning "to eat").[5]

Geographical distribution

Wolof is spoken by more than 10 million people and about 40 percent (approximately 5 million people) of Senegal's population speak Wolof as their native language. Increased mobility, and especially the growth of the capital Dakar, created the need for a common language: today, an additional 40 percent of the population speak Wolof as a second or acquired language. In the whole region from Dakar to Saint-Louis, and also west and southwest of Kaolack, Wolof is spoken by the vast majority of people. Typically when various ethnic groups in Senegal come together in cities and towns, they speak Wolof. It is therefore spoken in almost every regional and departmental capital in Senegal. Nevertheless, the official language of Senegal is French.

In The Gambia, although about 20–25 percent of the population speak Wolof as a first language, it has a disproportionate influence because of its prevalence in Banjul, the Gambian capital, where 75 percent of the population use it as a first language. Furthermore, in Serekunda, The Gambia's largest town, although only a tiny minority are ethnic Wolofs, approximately 70 percent of the population speaks or understands Wolof.

In Mauritania, about seven percent of the population (approximately 185,000 people) speak Wolof. Most live near or along the Senegal River that Mauritania shares with Senegal.

Classification

Wolof is one of the Senegambian languages, which are characterized by consonant mutation.[6] It is often said to be closely related to the Fula language because of a misreading by Wilson (1989) of the data in Sapir (1971) that have long been used to classify the Atlantic languages.

Varieties

Senegalese/Mauritanian Wolof and Gambian Wolof are distinct national standards: they use different orthographies and use different languages (French vs. English) as their source for technical loanwords. However, both the spoken and written languages are mutually intelligible. Lebu Wolof, on the other hand, is incomprehensible to standard Wolof speakers, a distinction that has been obscured because all Lebu speakers are bilingual in standard Wolof.[7]

Orthography and pronunciation

Note: Phonetic transcriptions are printed between square brackets [] following the rules of the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).

The Latin orthography of Wolof in Senegal was set by government decrees between 1971 and 1985. The language institute "Centre de linguistique appliquée de Dakar" (CLAD) is widely acknowledged as an authority when it comes to spelling rules for Wolof. The complete alphabet is A, À, B, C, D, E, É, Ë, F, G, I, J, K, L, M, N, Ñ, Ŋ, O, Ó, P, Q, R, S, T, U, W, X, Y. The letters H, V, and Z are only used in foreign words.[8][9][10]

Wolof is most often written in this orthography, in which phonemes have a clear one-to-one correspondence to graphemes. Table below is the Wolof Latin alphabet and the corresponding phoneme. Highlighted letters are only used for loanwords and are not included in native Wolof words.

| A a | À à | B b | C c | D d | E e | É é | Ë ë | F f | G g | H h | I i | J j | K k | L l | M m |

| [a] | [aː] | [b] | [c] | [d] | [ɛ] | [e] | [ə] | [f] | [ɡ] | ([h]) | [i] | [ɟ] | [k] | [l] | [m] |

| N n | Ñ ñ | Ŋ ŋ | O o | Ó ó | P p | Q q | R r | S s | T t | U u | V v | W w | X x | Y y | Z z |

| [n] | [ɲ] | [ŋ] | [ɔ] | [o] | [p] | [q] | [r] | [s] | [t] | [u] | ([w]) | [w] | [x] | [j] | ([ɟ]) |

The Arabic-based script of Wolof, referred to as Wolofal, was set by the government as well, between 1985 and 1990, although never adopted by a decree, as the effort by the Senegalese ministry of education was to be part of a multi-national standardization effort.[11] This alphabet has been used since pre-colonial times, as the first writing system to be adopted for Wolof, and is still used by many people, mainly Imams and their students in Quranic and Islamic schools.

| ا [∅]/[ʔ] |

ب [b] |

ݒ [p] |

ت [t] |

ݖ [c] |

ث [s] |

ج [ɟ] |

ح [h] |

خ [x] |

د [d] |

ذ [ɟ]~[z] |

| ر [r] |

ز [ɟ]~[z] |

س [s] |

ش [s]~[ʃ] |

ص [s] |

ض [d] |

ط [t] |

ظ [ɟ]~[z] |

ع [ʔ] |

غ [ɡ] |

ݝ [ŋ] |

| ف [f] |

ق [q] |

ک [k] |

گ [ɡ] |

ل [l] |

م [m] |

ن [n] |

ݧ [ɲ] |

ه [h] |

و [w] |

ي [j] |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Additionally, another script exists: Garay, an alphabetic script invented by Assane Faye 1961, which has been adopted by a small number of Wolof speakers.[13][14]

The first syllable of words is stressed; long vowels are pronounced with more time but are not automatically stressed, as they are in English.

Phonology

Vowels

The vowels are as follows:[15]

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | i ⟨i⟩ | iː | u ⟨u⟩ | uː | ||

| Close-mid | e ⟨é⟩ | eː | o ⟨ó⟩ | oː | ||

| mid | ə ⟨ë⟩ | |||||

| Open-mid | ɛ ⟨e⟩ | ɛː | ɔ ⟨o⟩ | ɔː | ||

| Open | a ⟨a⟩ | aː | ||||

There may be an additional low vowel, or this may be confused with orthographic à.[citation needed]

All vowels may be long (written double) or short.[16] /aː/ is written ⟨à⟩ before a long (prenasalized or geminate) consonant (example làmbi "arena"). When é and ó are written double, the accent mark is often only on the first letter.

Vowels fall into two harmonizing sets according to ATR: i u é ó ë are +ATR, e o a are the −ATR analogues of é ó ë. For example,[17]

Lekk-oon-ngeen

/lɛkːɔːnŋɡɛːn/

eat-PAST-FIN.2PL

'You (plural) ate.'

Dóor-óon-ngéen

/doːroːnŋɡeːn/

hit-PAST-FIN.2PL

'You (plural) hit.'

There are no −ATR analogs of the high vowels i u. They trigger +ATR harmony in suffixes when they occur in the root, but in a suffix, they may be transparent to vowel harmony.

The vowels of some suffixes or enclitics do not harmonize with preceding vowels. In most cases following vowels harmonize with them. That is, they reset the harmony, as if they were a separate word. However, when a suffix/clitic contains a high vowel (+ATR) that occurs after a −ATR root, any further suffixes harmonize with the root. That is, the +ATR suffix/clitic is "transparent" to vowel harmony. An example is the negative -u- in,

Door-u-ma-leen-fa

/dɔːrumalɛːnfa/

begin-NEG-1SG-3PL-LOC

'I did not begin them there.'

where harmony would predict *door-u-më-léén-fë. That is, I or U behave as if they are their own −ATR analogs.

Authors differ in whether they indicate vowel harmony in writing, as well as whether they write clitics as separate words.

Consonants

Consonants in word-initial position are as follows:[18]

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ɲ ⟨ñ⟩ | ŋ ⟨ŋ⟩[19] | |||

| Plosive | prenasalized | ᵐb ⟨mb⟩ | ⁿd ⟨nd⟩ | ᶮɟ ⟨nj⟩ | ᵑɡ ⟨ng⟩ | ||

| voiced | b ⟨b⟩ | d ⟨d⟩ | ɟ ⟨j⟩ | ɡ ⟨g⟩ | |||

| voiceless | p ⟨p⟩ | t ⟨t⟩ | c ⟨c⟩ | k ⟨k⟩ | q ⟨q⟩ | ʔ | |

| Fricative | f ⟨f⟩ | s ⟨s⟩ | x~χ ⟨x⟩ | ||||

| Trill | r ⟨r⟩ | ||||||

| Approximant | w ⟨w⟩ | l ⟨l⟩ | j ⟨y⟩ | ||||

All simple nasals, oral stops apart from q and glottal, and the sonorants l r y w may be geminated (doubled), though geminate r only occurs in ideophones.[20][21] (Geminate consonants are written double.) Q is inherently geminate and may occur in an initial position; otherwise, geminate consonants and consonant clusters, including nt, nc, nk, nq ([ɴq]), are restricted to word-medial and -final position. In the final place, geminate consonants may be followed by a faint epenthetic schwa vowel.

Of the consonants in the chart above, p d c k do not occur in the intermediate or final position, being replaced by f r s and zero, though geminate pp dd cc kk are common. Phonetic p c k do occur finally, but only as allophones of b j g due to final devoicing.

- bët ("eye") - bëtt ("to find")

- boy ("to catch fire") - boyy ("to be glimmering")

- dag ("a royal servant") - dagg ("to cut")

- dëj ("funeral") - dëjj ("cunt")

- fen ("to (tell a) lie") - fenn ("somewhere, nowhere")

- gal ("white gold") - gall ("to regurgitate")

- goŋ ("baboon") - goŋŋ (a kind of bed)

- gëm ("to believe") - gëmm ("to close one's eyes")

- Jaw (a family name) - jaww ("heaven")

- nëb ("rotten") - nëbb ("to hide")

- woñ ("thread") - woññ ("to count")

Tones

Unlike most sub-Saharan African languages, Wolof has no tones. Other non-tonal languages of sub-Saharan Africa include Amharic, Swahili and Fula.

Grammar

Notable characteristics

Pronoun conjugation instead of verbal conjugation

In Wolof, verbs are unchangeable stems that cannot be conjugated. To express different tenses or aspects of an action, personal pronouns are conjugated – not the verbs. Therefore, the term temporal pronoun has become established for this part of speech. It is also referred to as a focus form.[24]

Example: The verb dem means "to go" and cannot be changed; the temporal pronoun maa ngi means "I/me, here and now"; the temporal pronoun dinaa means "I am soon / I will soon / I will be soon". With that, the following sentences can be built now: Maa ngi dem. "I am going (here and now)." – Dinaa dem. "I will go (soon)."

Conjugation with respect to aspect instead of tense

In Wolof, tenses like present tense, past tense, and future tense are just of secondary importance and play almost no role. Of crucial importance is the aspect of action from the speaker's point of view. The most vital distinction is whether an action is perfective (finished) or imperfective (still going on from the speaker's point of view), regardless of whether the action itself takes place in the past, present, or future. Other aspects indicate whether an action takes place regularly, whether an action will surely take place and whether an actor wants to emphasize the role of the subject, predicate, or object.[clarification needed] As a result, conjugation is done by not tense but aspect. Nevertheless, the term temporal pronoun is usual for such conjugated pronouns although aspect pronoun might be a better term.

For example, the verb dem means "to go"; the temporal pronoun naa means "I already/definitely", the temporal pronoun dinaa means "I am soon / I will soon / I will be soon"; the temporal pronoun damay means "I (am) regularly/usually". The following sentences can be constructed: Dem naa. "I go already / I have already gone." – Dinaa dem. "I will go soon / I am just going to go." – Damay dem. "I usually/regularly/normally/am about to go."

A speaker may express that an action absolutely took place in the past by adding the suffix -(w)oon to the verb (in a sentence, the temporal pronoun is still used in a conjugated form along with the past marker):

Demoon naa Ndakaaru. "I already went to Dakar."

Action verbs versus static verbs and adjectives

Wolof has two main verb classes: dynamic and stative. Verbs are not inflected; instead pronouns are used to mark person, aspect, tense, and focus.[25]: 779

Consonant harmony

Gender

Wolof does not mark natural gender as grammatical gender: there is one pronoun encompassing the English 'he', 'she', and 'it'. The descriptors bu góor (male / masculine) or bu jigéen (female / feminine) are often added to words like xarit, 'friend', and rakk, 'younger sibling' to indicate the person's sex.

Markers of noun definiteness (usually called "definite articles") agree with the noun they modify. There are at least ten articles in Wolof, some of them indicating a singular noun, others a plural noun. In Urban Wolof, spoken in large cities like Dakar, the article -bi is often used as a generic article when the actual article is not known.

Any loan noun from French or English uses -bi: butik-bi, xarit-bi "the boutique, the friend."

Most Arabic or religious terms use -Ji: Jumma-Ji, jigéen-ji, "the mosque, the girl."

Four nouns referring to persons use -ki/-ñi: nit-ki, nit-ñi, "the person, the people"

Plural nouns use -yi: jigéen-yi, butik-yi, "the girls, the boutiques"

Miscellaneous articles: "si, gi, wi, mi, li."

Numerals

Cardinal numbers

The Wolof numeral system is based on the numbers 5 (quinary) and 10 (decimal). It is extremely regular in formation, comparable to Chinese. Example: benn "one", juróom "five", juróom-benn "six" (literally, "five-one"), fukk "ten", fukk ak juróom benn "sixteen" (literally, "ten and five one"), ñent-fukk "forty" (literally, "four-ten"). Alternatively, "thirty" is fanweer, which is roughly the number of days in a lunar month (literally "fan" is day and "weer" is moon.)

| 0 | tus / neen / zéro [French] / sero / dara ["nothing"] |

| 1 | benn |

| 2 | ñaar / yaar |

| 3 | ñett / ñatt / yett / yatt |

| 4 | ñeent / ñenent |

| 5 | juróom |

| 6 | juróom-benn |

| 7 | juróom-ñaar |

| 8 | juróom-ñett |

| 9 | juróom-ñeent |

| 10 | fukk |

| 11 | fukk ak benn |

| 12 | fukk ak ñaar |

| 13 | fukk ak ñett |

| 14 | fukk ak ñeent |

| 15 | fukk ak juróom |

| 16 | fukk ak juróom-benn |

| 17 | fukk ak juróom-ñaar |

| 18 | fukk ak juróom-ñett |

| 19 | fukk ak juróom-ñeent |

| 20 | ñaar-fukk |

| 26 | ñaar-fukk ak juróom-benn |

| 30 | ñett-fukk / fanweer |

| 40 | ñeent-fukk |

| 50 | juróom-fukk |

| 60 | juróom-benn-fukk |

| 66 | juróom-benn-fukk ak juróom-benn |

| 70 | juróom-ñaar-fukk |

| 80 | juróom-ñett-fukk |

| 90 | juróom-ñeent-fukk |

| 100 | téeméer |

| 101 | téeméer ak benn |

| 106 | téeméer ak juróom-benn |

| 110 | téeméer ak fukk |

| 200 | ñaari téeméer |

| 300 | ñetti téeméer |

| 400 | ñeenti téeméer |

| 500 | juróomi téeméer |

| 600 | juróom-benni téeméer |

| 700 | juróom-ñaari téeméer |

| 800 | juróom-ñetti téeméer |

| 900 | juróom-ñeenti téeméer |

| 1000 | junni / junne |

| 1100 | junni ak téeméer |

| 1600 | junni ak juróom-benni téeméer |

| 1945 | junni ak juróom-ñeenti téeméer ak ñeent-fukk ak juróom |

| 1969 | junni ak juróom-ñeenti téeméer ak juróom-benn-fukk ak juróom-ñeent |

| 2000 | ñaari junni |

| 3000 | ñetti junni |

| 4000 | ñeenti junni |

| 5000 | juróomi junni |

| 6000 | juróom-benni junni |

| 7000 | juróom-ñaari junni |

| 8000 | juróom-ñetti junni |

| 9000 | juróom-ñeenti junni |

| 10000 | fukki junni |

| 100000 | téeméeri junni |

| 1000000 | tamndareet / million |

Ordinal numbers

Ordinal numbers (first, second, third, etc.) are formed by adding the ending –éél (pronounced ayl) to the cardinal number.

For example, two is ñaar and second is ñaaréél

The one exception to this system is "first", which is bu njëk (or the adapted French word premier: përëmye)

| 1st | bu njëk |

| 2nd | ñaaréél |

| 3rd | ñettéél |

| 4th | ñeentéél |

| 5th | juróoméél |

| 6th | juróom-bennéél |

| 7th | juróom-ñaaréél |

| 8th | juróom-ñettéél |

| 9th | juróom-ñeentéél |

| 10th | fukkéél |

Personal pronouns

| subject | object | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| singular | plural | singular | plural | |

| 1st person | man | nun | ma | nu |

| 2nd person | yow | yeen | la | leen |

| 3rd person | moom | ñoom | ko | leen |

Temporal pronouns

Conjugation of the temporal pronouns

| 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| singular | plural | singular | plural | singular | plural | ||

| "I" | "we" | "you" | "you all" | "he/she/it" | "they" | ||

| Situative (Presentative) | Perfect | maa ngi | nu ngi | yaa ngi | yéena ngi | mu ngi | ñu ngi |

| Imperfect | maa ngiy | nu ngiy | yaa ngiy | yéena ngiy | mu ngiy | ñu ngiy | |

| Terminative | Perfect | naa | nanu | nga | ngeen | na | nañu |

| Future | dinaa | dinanu | dinga | dingeen | dina | dinañu | |

| Objective | Perfect | laa | lanu | nga | ngeen | la | lañu |

| Imperfect | laay | lanuy | ngay | ngeen di | lay | lañuy | |

| Processive (Explicative and/or Descriptive) |

Perfect | dama | danu | danga | dangeen | dafa | dañu |

| Imperfect | damay | danuy | dangay | dangeen di | dafay | dañuy | |

| Subjective | Perfect | maa | noo | yaa | yéena | moo | ñoo |

| Imperfect | maay | nooy | yaay | yéenay | mooy | ñooy | |

| Neutral | Perfect | ma | nu | nga | ngeen | mu | ñu |

| Imperfect | may | nuy | ngay | ngeen di | muy | ñuy | |

In urban Wolof, it is common to use the forms of the 3rd person plural also for the 1st person plural.

It is also important to note that the verb follows specific temporal pronouns and precedes others.

Examples

Sample phrases[26]

| English | Wolof |

|---|---|

| Hello. | Nuyu naala. |

| Yes. | Waaw. |

| Yes please. | Waaw jërëjëf. |

| No. | Déet. |

| No thanks. | Baax na, jërëjëf. |

| Please. | Ma ngi lay ñaan. |

| Thank you. | Jërëjëf. |

| Thank you very much. | Maangilay sant bu baax. |

| You're welcome. | Ñoo ko bokk. |

| I'd like a coffee please. | Kafe laa bëgg, nga baalma. |

| Excuse me. | Nga baalma. |

| What time is it? | Ban waxtu moo jot? |

| Can you repeat that please? | Baamtuwaat ko, nga baalma? |

| Please speak more slowly. | Waxal ndank. |

| I don't understand. | Xawma li nga bëgg wax. |

| Sorry. | Baal ma. |

| Where are the toilets? | Ani wanag yi? |

| How much does this cost? | Bii ñaata lay jar? |

| Welcome! | Dalal-jàmm! |

| Good morning. | Suba ak jàmm. |

| Good afternoon. | Ngoonu jàmm. |

| Good evening. | Guddig jàmm. |

| Good night. | Ñu fanaan ci jàmm. |

| Goodbye. | Ba beneen yóon. |

Literature

The New Testament was translated into Wolof and published in 1987, second edition 2004, and in 2008 with some minor typographical corrections.[27]

Boubacar Boris Diop published his novel Doomi Golo in Wolof in 2002.[28]

The 1994 song "7 Seconds" by Youssou N'Dour and Neneh Cherry is partially sung in Wolof.

Oral literature

In his 1865 collection of West African proverbs, Wit and Wisdom from West Africa,[29] Richard Francis Burton included a selection of over 200 Wolof proverbs in both Wolof and English translation[30] drawn from Jean Dard's Grammaire Wolofe of 1826.[31] Here are some of those proverbs:

- "Jalele sainou ane na ainou guissetil dara, tey mague dieki thy soufe guissa yope." "The child looks everywhere and often sees nought, but the old man, sitting on the ground, sees everything." (#2)

- "Poudhie ou naigue de na jaija ah taw, tey sailo yagoul." "The roof fights with the rain, but he who is sheltered ignores it." (#8)

- "Sopa bour ayoul, wandy bour bou la sopa a ko guenne." "To love the king is not bad, but a king who loves you is better." (#16)

- "Lou mpithie nana, nanetil nane ou gneye." "The bird can drink much, but the elephant drinks more." (#68)

In the appendix to his Folktales from the Gambia, Emil Magel, a professor of African literature and of Swahili,[32] included the Wolof text of the story of "The Donkeys of Jolof," "Fari Mbam Ci Rew i Jolof"[33] accompanied by an English translation.[34]

In his Grammaire de la Langue Woloffe published in 1858, David Boilat, a Senegalese writer and missionary,[35] included a selection of Wolof proverbs, riddles and folktales accompanied by French translations.[36]

Du Tieddo au Talibé by Lilyan Kesteloot and Bassirou Dieng, published in 1989,[37] is a collection of traditional tales in Wolof with French translations. The stories come from the Wolof monarchies that ruled Senegal from the 13th to the beginning of the 20th century.

Sample text

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

| Translation | Latin Script | Wolofal (Arabic) Script |

|---|---|---|

| All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. | Doomi aadama yépp danuy juddu, yam ci tawfeex ci sag ak sañ-sañ. Nekk na it ku xam dëgg te ànd na ak xelam, te war naa jëflante ak nawleen, te teg ko ci wàllu mbokk. | دࣷومِ آدَمَ يࣺݒّ دَنُيْ جُدُّ، يَمْ ݖِ تَوفࣹيخْ ݖِ سَگْ اَکْ سَݧْ-سَݧْ. نࣹکّ نَ اِتْ کُ خَمْ دࣴگّ تࣹ اࣵندْ نَ خࣹلَمْ، تࣹ وَرْ نَا جࣴفْلَنْتࣹ اَکْ نَوْلࣹينْ، تࣹ تࣹگْ کࣷ ݖِ وࣵلُّ مبࣷکّ. |

See also

References

- ^ a b Wolof at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

Gambian Wolof at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ "Wolof". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Wolof Brochure" (PDF). Indiana.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-09-04. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "banana". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ Danielle D'Offay & Guy Lionet, Diksyonner Kreol-Franse / Dictionnaire Créole Seychellois – Français, Helmut Buske Verlag, Hamburg, 1982. In all fairness, the word might as easily be from Fula nyaamde, "to eat".

- ^ Torrence, Harold The Clause Structure of Wolof: Insights Into the Left Periphery, John Benjamins Publishing, 2013, p. 20, ISBN 9789027255815 [1]

- ^ Hammarström (2015) Ethnologue 16/17/18th editions: a comprehensive review: online appendices

- ^ "Orthographe et prononciation du wolof | Jangileen". jangileen.kalam-alami.net (in French). Retrieved 2017-05-30.

- ^ Diouf, Jean-Léopold (2003). Dictionnaire wolof-français et français-wolof. Karthala. p. 35. ISBN 284586454X. OCLC 937136481.

- ^ Diouf, Jean-Léopold; Yaguello, Marina (January 1991). J'apprends le wolof Damay jàng wolof. Karthala. p. 11. ISBN 2865372871. OCLC 938108174.

- ^ a b Priest, Lorna A; Hosken, Martin; SIL International (12 August 2010). "Proposal to add Arabic script characters for African and Asian languages" (PDF). pp. 13–18, 34–37.

- ^ Currah, Galien (26 August 2015) ORTHOGRAPHE WOLOFAL. Link (Archive)

- ^ Everson, Michael (26 April 2012). "Preliminary proposal for encoding the Garay script in the SMP of the UCS" (PDF). UC Berkeley Script Encoding Initiative (Universal Scripts Project)/International Organization for Standardization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-08-19. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ Ager, Simon. "Wolof". Omniglot. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ Unseth, 2009.

- ^ Long ëë is rare (Torrence 2013:10).

- ^ Torrence 2013:11

- ^ Omar Ka, 1994, Wolof Phonology and Morphology

- ^ Or ⟨n̈⟩ in some texts.

- ^ Pape Amadou Gaye, Practical Cours in / Cours Practique en Wolof: An Audio–Aural Approach.

- ^ Some are restricted or rare, and sources disagree about this. Torrence (2013) claims that all consonants but prenasalized stops may be geminate, while Diouf (2009) does not list the fricatives, q, or r y w, and does not recognize glottal stop in the inventor. The differences may be dialectical or because some sounds are rare.

- ^ Diouf (2009)

- ^ "Wollof - English Dictionary" (PDF). Peace Corps The Gambia. 1995. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-06-23. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- ^ Ngom, Fallou (2003-01-01). Wolof. Lincom. ISBN 9783895868450.

- ^ Campbell, George; King, Gareth (2011). The Concise Compendium of the World's Languages (2 ed.).

- ^ "Learn Wolof with uTalk". utalk.com. Retrieved 2024-04-09.

- ^ "Biblewolof.com". Biblewolof.com. Retrieved 2013-04-15.

- ^ Encyclopedia of African Literature, p 801

- ^ Burton, Richard (1865). Wit and Wisdom from West Africa.

- ^ Burton 1865, pp. 3-37.

- ^ Dard, Jean (1826). Grammaire Wolofe.

- ^ Obituary for Emil Anthony (Terry) Magel, 1945-2024. Harrod Brothers Funeral Home. Accessed July 23 2024.

- ^ Magil, Emil (1984). Folktales from the Gambia: Wolof Fictional Narratives. pp. 205-208.

- ^ Magil 1984, pp. 154-157.

- ^ Boilat, David, abbé (1814—1901) Oxford Reference. Accessed July 23 2024.

- ^ Boilat, David (1858). Grammaire de la Langue Woloffe. pp. 372-412.

- ^ Kesteloot, Lilyan; Dieng, Bassirou. (1989). Du Tieddo au Talibé: Contes et Mythes Wolof .

Bibliography

- Linguistics

- Bichler, Gabriele Aïscha (2003). "Bejo, Curay und Bin-bim? Die Sprache und Kultur der Wolof im Senegal (mit angeschlossenem Lehrbuch Wolof)". Europäische Hochschulschriften. Vol. 90. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Verlagsgruppe. ISBN 3-631-39815-8.

- Cisse, Momar (February 2005). "Linguistique de la langue et linguistique du discours. Deux approches complémentaires de la phrase wolof, unité sémantico-syntaxique". Sudlangues. Archived from the original on 2006-12-16.

- Cissé, Mamadou (June 2000). "Graphical borrowing and African realities". Revue du Musée National d'Ethnologie d'Osaka.

- Cissé, Mamadou. ""Revisiter 'La grammaire de la langue wolof' d'A. Kobes (1869), ou étude critique d'un pan de l'histoire de la grammaire du wolof" (PDF). Sudlangues: Revue électronique internationale de sciences du langage. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-08.

- Ka, Omar (1994). Wolof Phonology and Morphology. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. ISBN 0-8191-9288-0.

- McLaughlin, Fiona (2001). "Dakar Wolof and the configuration of an urban identity". Journal of African Cultural Studies. 14 (2): 153–172. doi:10.1080/13696810120107104.

- McLaughlin, Fiona (2022). "Senegal: urban Wolof then and now". Urban Contact Dialects and Language Change. Routledge. pp. 47–65.

- Rialland, Annie; Robert, Stéphane (2001). "The intonation system of Wolof". Linguistics. 39 (5): 893–939. doi:10.1515/ling.2001.038.

- Swigart, Leigh (1992). "Two codes or one? The insiders' view and the description of codeswitching in Dakar". In Eastman, Carol M. (ed.). Codeswitching. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 1-85359-167-X.

- Torrence, Harold (2013). The Clause Structure of Wolof: Insights into the Left Periphery. Benjamins.

- Unseth, Carla (2009). "Vowel Harmony in Wolof" (PDF). Occasional Papers in Applied Linguistics. 7. Dallas International University.

- Grammar

- Camara, Sana (2006). Wolof Lexicon and Grammar. NALRC Press. ISBN 978-1-59703-012-0.

- Diagne, Pathé (1971). Grammaire de Wolof Moderne. Paris: Présence Africaine.

- Diouf, Jean-Léopold (2003). Grammaire du wolof contemporain. Paris: Karthala. ISBN 2-84586-267-9.

- Diouf, Jean-Léopold; Yaguello, Marina (1991). J'apprends le Wolof – Damay jàng wolof. Paris: Karthala. ISBN 2-86537-287-1. — 1 textbook with 4 audio cassettes.

- Franke, Michael (2002). Kauderwelsch, Wolof für den Senegal – Wort für Wort. Bielefeld: Reise Know-How Verlag. ISBN 3-89416-280-5.

- Franke, Michael; Diouf, Jean Léopold; Pozdniakov, Konstantin (2004). Le wolof de poche – Kit de conversation. Chennevières-sur-Marne, France: Assimil. ISBN 978-2-7005-4020-8. — (Phrasebook/grammar with 1 CD).

- Gaye, Pape Amadou (1980). Wolof: An Audio-Aural Approach. United States Peace Corps.

- Malherbe, Michel; Sall, Cheikh (1989). Parlons Wolof – Langue et culture. Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 2-7384-0383-2. — this book uses a simplified orthography which is not compliant with the CLAD standards; a CD is available.

- Ngom, Fallou (2003). Wolof. Munich: LINCOM. ISBN 3-89586-616-4.

- Samb, Amar (1983). Initiation a la Grammaire Wolof. Ifan-Dakar: Institut Fondamental d'Afrique Noire, Université de Dakar.

- Dictionaries

- Cissé, Mamadou (1998). Dictionnaire Français-Wolof. Paris: L’Asiathèque. ISBN 2-911053-43-5.

- Arame Fal, Rosine Santos, Jean Léonce Doneux: Dictionnaire wolof-français (suivi d'un index français-wolof). Karthala, Paris, France 1990, ISBN 2-86537-233-2.

- Pamela Munro, Dieynaba Gaye: Ay Baati Wolof – A Wolof Dictionary. UCLA Occasional Papers in Linguistics, No. 19, Los Angeles, California, 1997.

- Peace Corps Gambia: Wollof-English Dictionary, PO Box 582, Banjul, the Gambia, 1995 (no ISBN; this book refers solely to the dialect spoken in the Gambia and does not use the standard orthography of CLAD).

- Nyima Kantorek: Wolof Dictionary & Phrasebook, Hippocrene Books, 2005, ISBN 0-7818-1086-8 (this book refers predominantly to the dialect spoken in the Gambia and does not use the standard orthography of CLAD).

- Sana Camara: Wolof Lexicon and Grammar, NALRC Press, 2006, ISBN 978-1-59703-012-0.

- Official documents

- Government of Senegal, Décret n° 71-566 du 21 mai 1971 relatif à la transcription des langues nationales, modifié par décret n° 72-702 du 16 juin 1972.

- Government of Senegal, Décrets n° 75-1026 du 10 octobre 1975 et n° 85-1232 du 20 novembre 1985 relatifs à l'orthographe et à la séparation des mots en wolof.

- Government of Senegal, Décret n° 2005-992 du 21 octobre 2005 relatif à l'orthographe et à la séparation des mots en wolof.

External links

- Wolof resource (Mofeko, Omotola Akindipe & Joanna Senghore), Largest online resource to learn Wolof (with Gambian influence)

- Easy wolof (iPhone application)

- Wolof Language Resources Archived 2008-06-02 at the Wayback Machine

- An Annotated Guide to Learning the Wolof Language

- Wolof Online

- A French-Wolof-French dictionary partially available at Google Books.

- PanAfrican L10n page on Wolof

- OSAD spécialisée dans l’éducation nonformelle et l’édition des Ouvrages en Langues nationales Archived 2008-05-13 at the Wayback Machine