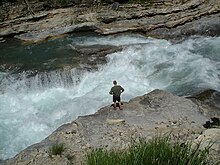

Whitewater

Whitewater forms in the context of rapids, in particular, when a river's gradient changes enough to generate so much turbulence that air is trapped within the water. This forms an unstable current that froths, making the water appear opaque and white.

The term "whitewater" also has a broader meaning, applying to any river or creek that has a significant number of rapids. The term is also used as an adjective describing boating on such rivers, such as whitewater canoeing or whitewater kayaking.[1]

Fast rivers

Four factors, separately or in combination, can create rapids: gradient, constriction, obstruction, and flow rate. Gradient, constriction, and obstruction are streambed topography factors and are relatively consistent. Flow rate is dependent upon both seasonal variation in precipitation and snowmelt and upon release rates of upstream dams.

Streambed topography

Streambed topography is the primary factor in creating rapids, and is generally consistent over time. Increased flow, as during a flood or high-rainfall season, can make permanent changes to the streambed by displacing rocks and boulders, by deposition of alluvium, or by creating new channels for flowing water.

Gradient

The gradient of a river is the rate at which it changes elevation along its course. This loss determines the river's slope, and to a large extent its rate of flow (velocity). Shallow gradients produce gentle, slow rivers, while steep gradients are associated with raging torrents.

Constriction

Constrictions can form a rapid when a river's flow is forced into a narrower channel. This pressure causes the water to flow more rapidly and to react to riverbed events (rocks, drops, etc.).

Obstruction

A boulder or ledge in the middle of a river or near the side can obstruct the flow of the river, and can also create a "pillow"; when water flows backwards upstream of the obstruction, or a "pour over" (over the boulder); and "hydraulics" or "holes" where the river flows back on itself—perhaps back under the drop—often with fearful results for those caught in its grasp. (Holes, or hydraulics, are so-called because their foamy, aerated water provides less buoyancy and can feel like an actual hole in the river surface.) If the flow passes next to the obstruction, an eddy may form behind the obstruction; although eddies are typically sheltered areas where boaters can stop to rest, scout, or leave the main current, they may be swirling and whirlpool-like. As with hydraulics (which pull downward rather than to the side and are essentially eddies turned at a 90° angle), the power of eddies increases with the flow rate.[citation needed]

In large rivers with high flow rates next to an obstruction, "eddy walls" can occur. An eddy wall is formed when the height of the river is substantially higher than the level of the water in the eddy behind the obstruction. This can make it difficult for a boater, who has stopped in that particular eddy, to re-enter the river due to a wall of water that can be several feet high at the point at which the eddy meets the river flow.

Stream flow rate

A marked increase or decrease in flow can create a rapid, "wash out" a rapid (decreasing the hazard), or make safe passage through previously navigable rapids more difficult or impossible. Flow rate is measured in volume per unit of time. The stream flow rate may be faster for different parts of a river, such as if there's an undercurrent.[2]

Classification

The most widely used[citation needed] grading system is the International Scale of River Difficulty, where whitewater (either an individual rapid, or the entire river) is classed in six categories from class I (the easiest and safest) to class VI (the most difficult and most dangerous). The grade reflects both the technical difficulty and the danger associated with a rapid, with grade I referring to flat or slow-moving water with few hazards, and grade VI referring to the hardest rapids, which are very dangerous even for expert paddlers, and are rarely run. Grade-VI rapids are sometimes downgraded to grade-V or V+ if they have been run successfully. Harder rapids (for example a grade-V rapid on a mainly grade-III river) are often portaged, a French term for carrying. A portaged rapid is where the boater lands and carries the boat around the hazard. (In many cases, a lower rated rapid may give a better "ride" to kayakers or rafters, while a Class V may seem relatively tame. However, it is not so much the "ride," but the inherent danger in the rapid. An exiting rapid may have minimal risk, while a seemingly simply rapid may have terminal hydraulics, undercut rocks, etc.)

A rapid's grade is not fixed, since it may vary greatly depending on the water depth and speed of flow. Also, the level of development in rafting/kayaking technology plays a role. Rapids that would have meant almost certain death a hundred years ago may now be considered only a Class IV or V rapid, due to the development of certain safety features. Although some rapids may be easier at high flows because features are covered or "washed-out", high water usually makes rapids more difficult and dangerous. At flood stage, even rapids that are usually easy can contain lethal and unpredictable hazards (briefly adapted from the American version[3] of the International Scale of River Difficulty).

- Class 1: Very small rough areas, requires no maneuvering (skill level: none)

- Class 2: Some rough water, maybe some rocks, small drops, might require maneuvering (skill level: basic paddling)

- Class 3: Medium waves, maybe a 3–5 ft drop, but not much considerable danger, may require significant maneuvering (skill level: experienced paddling)

- Class 4: Whitewater, large waves, long rapids, rocks, maybe a considerable drop, sharp maneuvers may be needed (skill level: advanced whitewater experience)

- Class 5: Approaching to the upper limits of rapids that can be run with the paddling skill (a Class 6 rapid has more to do with luck than skill, at least skill that can do much more than simply avoid the meat of the rapid). Whitewater, large waves, continuous rapids, large rocks and hazards, maybe a large drop, precise maneuvering, often characterized by "must make" moves, i.e. failure to execute a specific maneuver at a specific point may result in serious injury or death, Class 5 sometimes expanded to Class 5+ that describes the most extreme, runnable rapids (skill level: expert); Class 5+ is sometimes assigned to a rapid for commercial purposes, since insurance companies often will not cover losses sustained in a Class 6 rapid.

- Class 6: While some debate exists over the term "class 6", in practice it refers to rapids that are not passable and any attempt to do so would has considerable risk of serious injury, near drowning, or death (e.g. Murchison Falls). If a rapid is run that was once thought to be impassible, it is typically reclassified as class 5.

Features found in whitewater

On any given rapid, a multitude of different features can arise from the interplay between the shape of the riverbed and the velocity of the water in the stream.

Strainers or sifts

Strainers are formed when an object blocks the passage of larger objects, but allows the flow of water to continue – like a big food strainer or colander. These objects can be very dangerous, because the force of the water will pin an object or body against the strainer and then pile up, pushing it down under water. For a person caught in this position, getting to safety will be difficult or impossible, often leading to a fatal outcome.

Strainers are formed by many natural or man-made objects, such as storm grates over tunnels, trees that have fallen into a river ("log jam"), bushes by the side of the river that are flooded during high water, wire fence, rebar from broken concrete structures in the water, or other debris. Strainers occur naturally most often on the outside curves of rivers where the current undermines the shore, exposing the roots of trees and causing them to fall into the river and form strainers.

In an emergency, climbing on top of a strainer may be better so as not to be pinned against the object under the water. In a river, swimming aggressively away from the strainer and into the main channel is recommended. If avoiding the strainer is not possible, one should swim hard towards it and try to get as much of one's body up and over it as possible.

Sweepers

Sweepers are trees fallen in or heavily leaning over the river, still rooted on the shore and not fully submerged. Their trunks and branches may form an obstruction in the river like strainers. Since it is an obstruction from above, it often does not contribute to whitewater features, but may create turbulence. In fast water, sweepers can pose a serious hazard to paddlers.

Holes

Holes, or "hydraulics", (also known as "stoppers" or "souse-holes" (see also Pillows) are formed when water pours over the top of a submerged object, or underwater ledges, causing the surface water to flow back upstream toward the object. Holes can be particularly dangerous—a boater or watercraft may become stuck under the surface in the recirculating water—or entertaining play-spots, where paddlers use the holes' features to perform various playboating moves. In high-volume water flows, holes can subtly aerate the water, enough to allow craft to fall through the aerated water to the bottom of a deep 'hole'.

Some of the most dangerous types of holes are formed by low-head dams (weirs), and similar types of obstructions. In a low-head dam, the 'hole' has a very wide, uniform structure with no escape point, and the sides of the hydraulic (ends of the dam) are often blocked by a man-made wall, making paddling around, or slipping off, the side of the hydraulic, where the bypass water flow would become normal (laminar), difficult. By (upside-down) analogy, this would be much like a surfer slipping out the end of the pipeline, where the wave no longer breaks. Low-head dams are insidiously dangerous because their danger cannot be easily recognized by people who have not studied swift water. (Even 'experts' have died in them.) Floating debris (trees, kayaks, etc.) is often trapped in these retroflow 'grinders' for weeks at a time.[4]

Waves

Waves are formed in a similar manner to hydraulics and are sometimes also considered hydraulics, as well. Waves are noted by the large, smooth face on the water rushing down. Sometimes, a particularly large wave also is followed by a "wave train", a long series of waves. These standing waves can be smooth, or particularly the larger ones, can be breaking waves (also called "whitecaps" or "haystacks").

Because of the rough and random pattern of a riverbed, waves are often not perpendicular to the river's current. This makes them challenging for boaters, since a strong sideways or diagonal (also called a "lateral") wave can throw the craft off if the craft hits sideways or at an angle. The safest move for a whitewater boater approaching a lateral is to "square up" or turn the boat such that it hits the wave along the boat's longest axis, reducing the chance of the boat flipping or capsizing. This is often counterintuitive because it requires turning the boat such that it is no longer parallel to the current.

In fluid mechanics, waves are classified as laminar, but the whitewater world has also included waves with turbulence ("breaking waves") under the general heading of waves.

Pillows

Pillows are formed when a large flow of water runs into a large obstruction, causing water to "pile up" or "boil" against the face of the obstruction. Pillows normally signal that a rock is not undercut. Pillows are also known as "pressure waves".

Eddies

Eddies are formed, like hydraulics, on the downstream face of an obstruction. Unlike hydraulics, which swirl vertically in the water column, eddies revolve on the horizontal surface of the water. Typically, they are calm spots where the downward movement of water is partially or fully arrested—a place to rest or to make one's way upstream. However, in very powerful water, eddies can have powerful, swirling currents that trap or even can flip boats[citation needed] and from which escape can be very difficult.

Eddy Lines

Located between the eddy and the main current, the eddy line is a swirling seam of green and sometimes white water. Eddy lines vary in size based on the size of the water column, the gradient of the section, and the obstacle creating the eddy. Often containing boils and whirlpools, eddy lines can spin and grab your watercraft in unexpected ways, but if used correctly, they can be a really playful spot. Full slice and half slice boaters are able to perform tricks like stern squirts and cartwheels, but nobody uses eddy lines as well as squirt boaters(link to squirt boating wiki), who use the swirling water and crossing currents to dance below the surface of the river.

Undercut rocks

Undercut rocks have been worn down underneath the surface by the river, or are loose boulders which cantilever out beyond their resting spots on the riverbed. They can be extremely dangerous features of a rapid because a person can get trapped underneath them under water. This is especially true of rocks that are undercut on the upstream side. Here, a boater may become pinned against the rock under water. Many whitewater deaths have occurred in this fashion. Undercuts sometimes have pillows, but other times the water just flows smoothly under them, which can indicate that the rock is undercut. Undercuts are most common in rivers where the riverbed cuts through sedimentary rocks such as limestone rather than igneous rock such as granite. In a steep canyon, the side walls of the canyon can also be undercut.

A particularly notorious undercut rock is Dimple Rock, in Dimple Rapid on the Lower Youghiogheny River, a very popular rafting and kayaking river in Pennsylvania. Of about nine people who have died at or near Dimple Rock, including three in 2000, several of the deaths were the result of people becoming entrapped after they were swept under the rock.[5] [6]

Sieves

Another major whitewater feature is a sieve, which is a narrow, empty space through which water flows between two obstructions, usually rocks. Similar to strainers, water is forced through the sieve, resulting in higher velocity flow, which forces water up and creates turbulence.

Whitewater craft

People use many types of whitewater craft to make their way down a rapid, preferably with finesse and control. Here is a short list of them:

Whitewater kayaks differ from sea kayaks and recreational kayaks in that they are better specialized to deal with moving water. They are often shorter and more maneuverable than sea kayaks and are specially designed to deal with water flowing up onto their decks. Most whitewater kayaks are made of plastics now, although some paddlers (especially racers and "squirt boaters") use kayaks made of fiberglass composites. Whitewater kayaks are fairly stable in turbulent water, once the paddler is skillful with them; if flipped upside-down, the skilled paddler can easily roll them back upright. This essential skill of whitewater kayaking is called the "Eskimo roll", or simply "roll". Kayaks are paddled in a low sitting position (legs extended forward), with a two-bladed paddle. See Whitewater kayaking.

Rafts are also often used as a whitewater craft; more stable than typical kayaks, they are less maneuverable. Rafts can carry large loads, so they are often used for expeditions. Typical whitewater rafts are inflatable craft, made from high-strength fabric coated with PVC, urethane, neoprene or Hypalon; see rafting. While most rafts are large multipassenger craft, the smallest rafts are single-person whitewater craft, see packraft. Rafts sometimes have inflatable floors, with holes around the edges, that allow water that splashes into the boat to easily flow to the side and out the bottom (these are typically called "self-bailers" because the occupants do not have to "bail" water out with a bucket). Others have simple fabric floors, without anyway for water to escape, these are called "bucket boats", both for their tendency to hold water like a bucket, and because the only way to get water out of them is by bailing with a bucket.

Catarafts are constructed from the same materials as rafts. They can either be paddled or rowed with oars. Typical catarafts are constructed from two inflatable pontoons on either side of the craft that are bridged by a frame. Oar-propelled catarafts have the occupants sitting on seats mounted on the frame. Virtually all oar-powered catarafts are operated by a boatsman with passengers having no direct responsibilities. Catarafts can be of all sizes; many are smaller and more maneuverable than a typical raft.

Canoes are often made of fiberglass, kevlar, plastic, or a combination of the three for strength and durability. They may have a spraycover, resembling a kayak, or be "open", resembling the typical canoe. This type of canoe is usually referred to simply as an "open boat". Whitewater canoes are paddled in a low kneeling position, with a one-bladed paddle. Open whitewater canoes often have large airbags and in some cases foam, usually 2-lb density ethyl foam, firmly attached to the sides, to displace water in the boat when swamped by big waves and holes and to allow water to be spilled from the boat while still in the river by floating it up on its side using the foam and bags. Like kayaks, whitewater canoes can be righted after capsizing with an Eskimo roll, but this requires more skill in a canoe.

C1s are similar in construction to whitewater kayaks, but they are paddled in a low, kneeling position. They employ the use of a one-blade paddle, usually a little shorter than used in a more traditional canoe. They have a spraycover, essentially the same type used in kayaking. Like kayaks, C1s can be righted after capsizing with an Eskimo roll.

McKenzie River dory (or "drift boat" by some) is a more traditional "hard sided" boat. The design is characterized by a wide, flat bottom, flared sides, a narrow, flat bow, a pointed stern, and extreme rocker in the bow and stern to allow the boat to spin about its center for ease in maneuvering in rapids.

River bugs are small, single-person, inflatable craft where a person's feet stick out of one end. River bugging is done feet first with no paddle.

Creature Craft are the ultimate whitewater craft, with a roll cage design that protects the occupants if they are to flip in any manner. You can see these creatures drifting down rivers like the Gauley, waiting to be capsized and righted by other enthusiastic river users.

Whitewater SUP (Stand Up Paddle Boarding), similar to traditional flat water stand up paddle boarding, whitewater SUPing involves the use of a stand up paddle board to run whitewater. The boards are typically specially designed for whitewater use, and more safety gear is used than on flat water.

Safety

Running whitewater rivers is a popular recreational sport, but is not without danger. Fast-moving water always has the potential for injury or death by drowning or hitting objects. Fatalities do occur; some 50 people die in whitewater accidents in the United States each year.[7] The dangers can be mitigated (but not eliminated) by training, experience, scouting, the use of safety equipment (such as personal flotation devices, helmets, throw ropes), and using other persons as "spotters".

Scouting or examining the rapids before running them is crucial to familiarize oneself with the stream and anticipate the challenges. This is especially important during flood conditions when the highly increased flows have altered the normal conditions drastically.

See also

- Fluid dynamics and Turbulence for an academic explanation of whitewater features

- List of whitewater rivers

- Slalom canoeing

- River surfing

References

- ^ "Glossary of canoe terms". Westlakes.canoe.org.au. West Lakes Canoe Club. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "How to Survive a Fast River Current". The Active Times. 10 June 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ "American Whitewater – Safety". Americanwhitewater.org. 27 July 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ NFPA-1006 Standard for Technical Rescuer

- ^ "Editorial: Rock on / Dimple Rock is left alone to be dangerous". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 2006-04-10. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- ^ "American Whitewate, Lower Yough accident reports". Americanwhitewater.org. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ Drew Griffin and James Polk (2006-09-06). "Whitewater deaths surge in U.S." CNN. Retrieved 2007-10-25.