Western gorilla

| Western gorilla[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

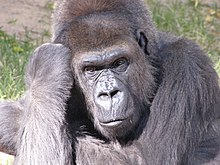

| Male at the San Francisco Zoo | |

| |

| Female with infant at the Bronx Zoo | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Genus: | Gorilla |

| Species: | G. gorilla |

| Binomial name | |

| Gorilla gorilla (Savage, 1847) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

Western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) | |

| |

| Western gorilla range. Each of the two subspecies is confined to two separate regions. Western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) Cross River gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) | |

The western gorilla (Gorilla gorilla) is a great ape found in Africa, one of two species of the hominid genus Gorilla. Large and robust with males weighing around 168 kilograms (370 lb), the species is found in a region of midwest Africa, geographically isolated from the eastern gorilla (Gorilla beringei). The hair of the western species is significantly lighter in color.

The western gorilla is the second largest living primate after the eastern gorilla. Two subspecies are recognised: the western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) is found in most of West Africa; while the Cross River gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) is limited to a smaller range in the north at the border of Cameroon and Nigeria. Both subspecies are listed Critically Endangered.

Taxonomy

A formal description of the species was provided by Thomas Savage in 1847, allying the new species to an earlier description of the chimpanzee as Troglodytes gorilla in a group of eastern simians he referred to as "orangs". The author selected the specific epithet for the name given by Hanno to "wild men" he had noted on the east coast of Africa, presumed by Savage to be a species of orang.[4] The population is recognised as two subspecies:

| Image | Subspecies | Population | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) | 276,000[2] | Angola, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Republic of the Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon. |

|

Cross River gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) | 250 to 300[5][6] | Cameroon-Nigeria border region. |

Nearly all of the individuals of this taxon belong to the western lowland gorilla subspecies, whose population is approximately 276,000 individuals. Only 250 to 300 of the only other western gorilla subspecies, the Cross River gorilla, are thought to remain.

Description

Western gorillas are generally lighter colored than eastern gorillas. Western gorillas have black, dark grey or dark brown-grey hair with a brownish forehead. Males average 167 cm (5 ft 5.7 in) although reaching a height up to 176 cm (5 ft 9.3 in), with males having an average weight of 168 kilograms (370 lb) and females weighing 58 to 72 kilograms (128 to 159 lb).[7] Captive western gorillas average 157 kg (346 lb) in males and 80 kg (176 lb) in females.[8] Another source[which?] describes the weight of wild male western lowland gorillas as 146 kg (322 lb).[9] The Cross River gorilla differs from the western lowland gorilla in both skull and tooth dimensions.

Behavior and ecology

Western gorillas live in groups that vary in size from two to twenty individuals. Such groups are composed of at least one male, several females and their offspring. A dominant male silverback heads the group, with younger males usually leaving the group when they reach maturity. Females transfer to another group before breeding, which begins at eight to nine years old; they care for their young infants for the first three to four years of their lives. The interval between births, therefore, is long, which partly explains the slow population growth rates that make the western gorilla so vulnerable to poaching. Due to the long gestation time, long period of parental care, and infant mortality, a female gorilla will only give birth to an offspring that survives to maturity every six to eight years. Western gorillas are long-lived and may survive for as long as 40 years in the wild. A group's home range may be as large as 30 km2 (12 sq mi), but is not actively defended. Wild western gorillas are known to use tools.[10]

Western gorillas' diets are high in fiber, including leaves, stems, fruit, piths, flowers, bark, invertebrates, and soil. The frequency of when each of these are consumed depends on the particular western gorilla group and the season. Furthermore, different groups of western gorillas eat differing numbers and species of plants and invertebrates, suggesting they have a food culture. Fruit comprises most of the western lowland gorillas' diets when it is abundant, directly influencing their foraging and ranging patterns. There is a correlation between the amount of time a western gorilla travels and the season in which fruits are available. Western gorillas spend more time traveling and feeding during the seasons when fruits are abundant compared to when there is less fruits available.[11] Fruits of the genera Tetrapleura, Chrysophyllum, Dialium, and Landolphia are favored by the western gorillas. Low-quality herbs, such as leaves and woody vegetation, are only eaten when fruit is scarce. In the dry season from January to March, when fleshy fruits are few and far between, more fibrous vegetation such as the leaves and bark of the low-quality herbs Palisota and Aframomum are consumed. Of the invertebrates consumed by the western gorillas, termites and ants make up the majority. Caterpillars, grubs, and larvae are also consumed in rarity.

Some ethnographic and pharmacological studies have suggested a possible medicinal value in particular foods consumed by the western gorilla. The fruit and seeds of multiple Cola species are consumed. Given the low protein content, the main reason for their consumption may be the stimulating effect of the caffeine in them. Western gorillas inhabiting Gabon have been observed consuming the fruit, stems, and roots of Tabernanthe iboga, which, due to the compound ibogaine in it, acts on the central nervous system, producing hallucinogenic effects. It also has effects comparable to caffeine.[12] There is also evidence for medicinal value for the seed pods of Aframomum melegueta in western gorillas' diets, which seem to have some sort of cardiovascular health benefit for western lowland gorillas, and are a known part of the natural diets for many wild populations.[13]

A study published in 2007 announced the discovery of this species fighting back against possible threats from humans.[14] They "found several instances of gorillas throwing sticks and clumps of grass".[15] This is unusual, because western gorillas usually flee and rarely charge when they encounter humans.

One mirror test in Gabon shows that western gorilla silverbacks react aggressively when faced with a mirror, although refusing to look fully at their reflection.[16]

Conservation status

The World Conservation Union lists the western gorilla as critically endangered, the most severe denomination next to global extinction, on its 2007 Red List of Threatened Species. The Ebola virus might be depleting western gorilla populations to a point where their recovery might become impossible, and the virus reduced populations in protected areas by 33% from 1992 to 2007, which may be equal to a decline of 45% for a period of just 20 years spanning 1992 to 2011.[2][17] Poaching, commercial logging and civil wars in the countries that compose the western gorillas' habitat are also threats.[17] Furthermore, reproductive rates are very low, with a maximum intrinsic rate of increase of about 3% and the high levels of decline from hunting and disease-induced mortality have caused declines in population of more than 60% over the last 20 to 25 years. Rather, under the optimistic estimate scenarios, population recovery would require almost 75 years. Yet within the next thirty years, habitat loss and degradation from agriculture, timber extraction, mining and climate change will become increasingly larger threats. Thus, a population reduction of more than 80% over three generations (i.e., 66 years from 1980 to 2046) seems likely.[citation needed] In the 1980s, a census taken of the gorilla populations in equatorial Africa was thought to be 100,000. Researchers adjusted the figure in 2008 after years of poaching and deforestation had reduced the population to approximately 50,000.[18]

Surveys conducted by the Wildlife Conservation Society in 2006 and 2007 found around 125,000 previously unreported gorillas have been living in the swamp forests of Lake Tele Community Reserve and in neighbouring Marantaceae (dryland) forests in the Republic of the Congo. This discovery could more than double the known population of the animals, though the effect that the discovery will have on the gorillas' conservation status is currently unknown.[18][19] With the new discovery, the current population of western lowland gorillas could be around 150,000–200,000. However, the gorilla remains vulnerable to Ebola, deforestation, and poaching.[18]

Estimates on the number of Cross River gorillas remaining is 250–300 in the wild, concentrated in approximately 9-11 locations.[5] Recent genetic research[20] and field surveys suggest that there is occasional migration of individual gorillas between locations. The nearest population of western lowland gorilla is some 250 km (160 mi) away. Both loss of habitat and intense hunting for bushmeat have contributed to the decline of this subspecies. In 2007, a conservation plan for the Cross River gorilla was published, outlining the most important actions necessary to preserve this subspecies.[21] The government of Cameroon has created the Takamanda National Park on the border with Nigeria, as an attempt to protect these gorillas.[22] The park now forms part of an important trans-boundary protected area with Nigeria's Cross River National Park, safeguarding an estimated 115 gorillas—a third of the Cross River gorilla population—along with other rare species.[23] The hope is that these gorillas will be able to move between the Takamanda reserve in Cameroon over the border to Nigeria's Cross River National Park.

Individuals

The names of individuals of the species includes:[citation needed]

References

- ^ Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 181–182. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c Maisels, F.; Bergl, R. A.; Williamson, E. A. (2016) [amended version of 2016 assessment]. "Gorilla gorilla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T9404A136250858.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Savage, T.S.; Wyman, J. (1847) [August 18, 1847]. "Notice of the external characters and habits of Troglodytes gorilla, a new species of orang from the gaboon river; osteology of the same". Boston Journal of Natural History. 5 (4): 417–443.

- ^ a b Oates, J. F.; Bergl, R. A.; Sunderland-Groves, J. & Dunn, A. (2008). "Gorilla gorilla ssp. diehli". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ "Animal Info – Gorilla". AnimalInfo.org. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ Kingdon, Jonathan (2013). Mammals of Africa: Volume II. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-4081-2257-0.

- ^ Leigh, S. R.; Shea, B. T. (1995). "Ontogeny and the evolution of adult body size dimorphism in apes". American Journal of Primatology. 36 (1): 37–60. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350360104. PMID 31924084. S2CID 85136825.

- ^ Taylor, Andrea B.; Goldsmith, Michele L., eds. (2002). Gorilla Biology: A Multidisciplinary Perspective. Cambridge Studies in Biological and Evolutionary Anthropology. Vol. 34. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1-139-43557-4. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ Breuer, T.; Ndoundou-Hockemba, M.; Fishlock, V. (2005). "First Observation of Tool Use in Wild Gorillas". PLOS Biology. 3 (11): e380. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030380. PMC 1236726. PMID 16187795.

- ^ Masi, Shelly; Cipolletta, Chloé; Robbins, Martha M. (February 2009). "Western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) change their activity patterns in response to frugivory". American Journal of Primatology. 71 (2): 91–100. doi:10.1002/ajp.20629. PMID 19021124. S2CID 4507112.

- ^ Caldecott, J., Miles, L., eds (2005) World Atlas of Great Apes and their Conservation. Prepared at the UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre. University of California Press, Berkeley, U.S.

- ^ "Gorilla diet protects heart: grains of paradise". Asknature.org. 20 February 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ Wittiger, L; Sunderland-Groves, J. L. (2007). "Tool use during display behavior in wild Cross River gorillas". American Journal of Primatology. 69 (11): 1307–11. doi:10.1002/ajp.20436. PMID 17410549. S2CID 19084217.

- ^ World's Most Endangered Gorilla Fights Back. Science Daily. 11 December 2007

- ^ Hubert-Brierre, Xavier (2015) Silverback always shows aggressiveness towards mirrors - Le dos argenté agresse toujours son reflet. YouTube

- ^ a b Planet Of No Apes? Experts Warn It's Close CBS News Online, 12 September 2007. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- ^ a b c "More than 100,000 rare gorillas found in Floral Park". CNN. 5 August 2008. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ^ "Thousands Of Rare Gorillas Found In Congo". Cbsnews.com. 5 August 2008. Retrieved 3 July 2009.

- ^ Bergl, R. A.; Vigilant, L (2007). "Genetic analysis reveals population structure and recent migration within the highly fragmented range of the Cross River gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli)". Molecular Ecology. 16 (3): 501–16. Bibcode:2007MolEc..16..501B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03159.x. PMID 17257109. S2CID 4150462.

- ^ Oates, J., Sunderland-Groves, J., Bergl, R., Dunn, A., Nicholas, A., Takang, E., Omeni, F., Imong, I., Fotso, R., Nkembi, L. and Williamson, E.A. (2007). Regional Action Plan for the Conservation of the Cross River Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli). IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group and Conservation International, Arlington, VA, U.S.

- ^ Black, Richard (28 November 2008) Protection boost for rare gorilla. BBC News.

- ^ New National Park Protects World's Rarest Gorilla. Newswise. 26 November 2008.

External links

- Western gorilla – silverbackgorillatours.com