Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia

| Operation Danube | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War and the Prague Spring | |||||||

Soviet T-54 in Prague during the invasion | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Logistics support: |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Initial invasion: 250,000 (20 divisions)[2] 2,000 tanks[3] 800 aircraft Peak strength:[citation needed] 350,000–400,000 Soviet troops, 70,000–80,000 from Poland, Bulgaria and Hungary[4] 6,300 tanks[5] |

235,000 (18 divisions)[6][7] 2,500–3,000 tanks | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

87 wounded[8] 5 soldiers committed suicide[9] | 137 civilians and soldiers killed,[12] 500 seriously wounded[13] | ||||||

| 70,000 Czechoslovak citizens fled to the West immediately after the invasion. Total number of emigrants before the Velvet Revolution reached 300,000.[14] | |||||||

On 20–21 August 1968, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was jointly invaded by four fellow Warsaw Pact countries: the Soviet Union, the Polish People's Republic, the People's Republic of Bulgaria, and the Hungarian People's Republic. The invasion stopped Alexander Dubček's Prague Spring liberalisation reforms and strengthened the authoritarian wing of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ).

About 250,000 Warsaw Pact troops (afterwards rising to about 500,000), supported by thousands of tanks and hundreds of aircraft, participated in the overnight operation, which was code-named Operation Danube. The Socialist Republic of Romania and the People's Republic of Albania refused to participate.[15][16] East German forces, except for a small number of specialists, were ordered by Moscow not to cross the Czechoslovak border just hours before the invasion,[17] because of fears of greater resistance if German troops were involved, due to public perception of the previous German occupation three decades earlier.[18] 137 Czechoslovaks were killed[12] and 500 seriously wounded during the occupation.[13]

Public reaction to the invasion was widespread and divided, including within the communist world. Although the majority of the Warsaw Pact supported the invasion along with several other communist parties worldwide, Western nations, along with socialist countries such as Romania, and particularly the People's Republic of China and People's Republic of Albania condemned the attack. Many other communist parties also lost influence, denounced the USSR, or split up or dissolved due to conflicting opinions. The invasion started a series of events that would ultimately pressure Brezhnev to establish a state of détente with U.S. President Richard Nixon in 1972 just months after the latter's historic visit to the PRC.

Background

| Eastern Bloc |

|---|

|

Novotný's regime: late 1950s – early 1960s

The process of de-Stalinization in Czechoslovakia had begun under Antonín Novotný in the late 1950s and early 1960s, but had progressed more slowly than in most other states of the Eastern Bloc.[19] Following the lead of Nikita Khrushchev, Novotný proclaimed the completion of socialism, and the new constitution,[20] accordingly, adopted the name Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. The pace of change, however, was sluggish; the rehabilitation of Stalinist-era victims, such as those convicted in the Slánský trials, may have been considered as early as 1963, but did not take place until 1967.

In the early 1960s, Czechoslovakia underwent an economic downturn. The Soviet model of industrialization applied unsuccessfully since Czechoslovakia was already entirely industrialized before World War II, and the Soviet model mainly took into account less developed economies. Novotný's attempt at restructuring the economy, the 1965 New Economic Model, spurred increased demand for political reform as well.

1967 Writers' Congress

As the strict government eased its rules, the Union of Czechoslovak Writers cautiously began to air discontent, and in the union's gazette, Literární noviny, members suggested that literature should be independent of Party doctrine. In June 1967, a small fraction of the Czech writer's union sympathized with radical socialists, specifically Ludvík Vaculík, Milan Kundera, Jan Procházka, Antonín Jaroslav Liehm, Pavel Kohout and Ivan Klíma. A few months later, at a party meeting, it was decided that administrative actions against the writers who openly expressed support of reformation would be taken. Since only a small part of the union held these beliefs, the remaining members were relied upon to discipline their colleagues. Control over Literární noviny and several other publishing houses was transferred to the Ministry of Culture, and even members of the party who later became significant reformers, including Dubček, endorsed these moves.

Prague Spring

The Prague Spring (Czech: Pražské jaro, Slovak: Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization in Czechoslovakia that began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ), and continued until 21 August when the Soviet Union and other members of the Warsaw Pact invaded the country to halt the reforms.

The Prague Spring reforms were a strong attempt by Dubček to grant additional rights to the citizens of Czechoslovakia in an act of partial decentralization of the economy and democratization. The freedoms granted included a loosening of restrictions on the media, speech and travel. After national discussion of dividing the country into a federation of three republics, Bohemia, Moravia–Silesia and Slovakia, Dubček oversaw the decision to split into two, the Czech Republic and Slovak Republic.[21]

Brezhnev's government

Leonid Brezhnev and the leadership of the Warsaw Pact countries were worried that the unfolding liberalizations in Czechoslovakia, including the ending of censorship and political surveillance by the secret police, would be detrimental to their interests. The first such fear was that Czechoslovakia would defect from the Eastern Bloc, injuring the Soviet Union's position in a possible Third World War with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Not only would the loss result in a lack of strategic depth for the USSR,[22] but it would also mean that it could not tap Czechoslovakia's industrial base in the event of war.[23] Czechoslovak leaders had no intention of leaving the Warsaw Pact, but Moscow felt it could not be certain exactly of Prague's intentions. However, the Soviet government was initially hesitant to approve an invasion, due to Czechoslovakia's continued loyalty to the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union's recent diplomatic gains with the West as détente began.[24]

Other fears included the spread of liberalization and unrest elsewhere in Eastern Europe. The Warsaw Pact countries feared that if the Prague Spring reforms went unchecked, then those ideals might very well spread to Poland and East Germany, upsetting the status quo there as well. Within the Soviet Union, nationalism in the republics of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Ukraine was already causing problems, and many were worried that events in Prague might exacerbate those problems.[25]

According to documents from the Ukrainian Archives, compiled by Mark Kramer, KGB chairman Yuri Andropov and Communist Party of Ukraine leaders Petro Shelest and Nikolai Podgorny were the most vehement proponents of military intervention.[26] The other version says that the initiative for the invasion came originally from Poland as the Polish First Secretary Władysław Gomułka and later his collaborator, East German First Secretary Walter Ulbricht, pressured Brezhnev to agree on the Warsaw Letter and on ensued military involvement.[27][28] Gomułka accused Brezhnev of being blind and looking at the situation in Czechoslovakia with too much of emotion. Ulbricht, in turn, insisted upon the necessity to enact military action in Czechoslovakia while Brezhnev was still doubting. Poland's foreign policy on the issue is still unknown. The deliberation that took place in Warsaw meeting, resulted in a majority consensus rather than unanimity.[citation needed] According to Soviet politician Konstantin Katushev, "our allies were even more worried than we were by what was going on in Prague. Gomulka, Ulbricht, Bulgarian First Secretary Todor Zhivkov, even Hungarian First Secretary János Kádár, all assessed the Prague Spring very negatively."[29] The "hardline" faction among Eastern bloc leaders was represented by Ulbricht and Gomułka. Ulbricht, worried about his own power and the stability of the East German state, disavowed the reforms vehemently early on, as evidenced in his letters by the fact that he was concerned and fearful about “the effects of the cancer" of Dubcekism in his own country.” [30] He continued to emphasize that Dubcek's reforms were "antirevolutionary" and a mockery of the Marxist-Leninist ideology he espoused, and as a result emphatically called out for military intervention at the Warsaw Conference in July 1968.[31]

In addition, part of Czechoslovakia bordered Austria and West Germany, which were on the other side of the Iron Curtain. This meant both that foreign agents could slip into Czechoslovakia and into any member of the Eastern bloc and that defectors could slip out to the West.[32] The final concern emerged directly from the lack of censorship; writers whose work had been censored in the Soviet Union could simply go to Prague or Bratislava and air their grievances there, circumventing the Soviet Union's censorship.

Dubček's rise to power

As President Antonín Novotný was losing support, Alexander Dubček, First Secretary of the regional Communist Party of Slovakia, and economist Ota Šik challenged him at a meeting of the Central Committee. Novotný then invited Soviet premier Leonid Brezhnev to Prague that December, seeking support; but Brezhnev was surprised at the extent of the opposition to Novotný and thus supported his removal as Czechoslovakia's leader. Dubček replaced Novotný as First Secretary on 5 January 1968. On 22 March 1968, Novotný resigned his presidency and was replaced by Ludvík Svoboda, who later gave consent to the reforms.[citation needed]

When the KSČ Presidium member Josef Smrkovský was interviewed in a Rudé Právo article, entitled "What Lies Ahead", he insisted that Dubček's appointment at the January Plenum would further the goals of socialism and maintain the working class nature of the Communist Party.[citation needed]

Socialism with a human face

On the 20th anniversary of Czechoslovakia's "Victorious February", Dubček delivered a speech explaining the need for change following the triumph of socialism. He emphasized the need to "enforce the leading role of the party more effectively"[33] and acknowledged that, despite Klement Gottwald's urgings for better relations with society, the Party had too often made heavy-handed rulings on trivial issues. Dubček declared the party's mission was "to build an advanced socialist society on sound economic foundations ... a socialism that corresponds to the historical democratic traditions of Czechoslovakia, in accordance with the experience of other communist parties ..."[33]

In April, Dubček launched an "Action Programme" of liberalizations, which included increasing freedom of the press, freedom of speech and freedom of movement, with economic emphasis on consumer goods and the possibility of a multiparty government. The programme was based on the view that "Socialism cannot mean only liberation of the working people from the domination of exploiting class relations, but must make more provisions for a fuller life of the personality than any bourgeois democracy."[34] It would limit the power of the secret police[35] and provide for the federalization of the ČSSR into two equal nations.[36] The programme also covered foreign policy, including both the maintenance of good relations with Western countries and cooperation with the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc nations.[37] It spoke of a ten-year transition through which democratic elections would be made possible and a new form of democratic socialism would replace the status quo.[38]

Those who drafted the Action Programme were careful not to criticize the actions of the post-war Communist regime, only to point out policies that they felt had outlived their usefulness.[39] For instance, the immediate post-war situation had required "centralist and directive-administrative methods"[39] to fight against the "remnants of the bourgeoisie."[39] Since the "antagonistic classes"[39] were said to have been defeated with the achievement of socialism, these methods were no longer necessary. Reform was needed, for the Czechoslovak economy to join the "scientific-technical revolution in the world"[39] rather than relying on Stalinist-era heavy industry, labour power, and raw materials.[39] Furthermore, since internal class conflict had been overcome, workers could now be duly rewarded for their qualifications and technical skills without contravening Marxism-Leninism. The Programme suggested it was now necessary to ensure important positions were "filled by capable, educated socialist expert cadres" in order to compete with capitalism.[39]

Although it was stipulated that reform must proceed under KSČ direction, popular pressure mounted to implement reforms immediately.[40] Radical elements became more vocal: anti-Soviet polemics appeared in the press (after the abolishment of censorship was formally confirmed by law of 26 June 1968),[38] the Social Democrats began to form a separate party, and new unaffiliated political clubs were created. Party conservatives urged repressive measures, but Dubček counselled moderation and re-emphasized KSČ leadership.[41] At the Presidium of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia in April, Dubček announced a political programme of "socialism with a human face".[42] In May, he announced that the Fourteenth Party Congress would convene in an early session on 9 September. The congress would incorporate the Action Programme into the party statutes, draft a federalization law, and elect a new Central Committee.[43]

Dubček's reforms guaranteed freedom of the press and political commentary was allowed for the first time in mainstream media.[44] At the time of the Prague Spring, Czechoslovak exports were declining in competitiveness, and Dubček's reforms planned to solve these troubles by mixing planned and market economies. Within the party, there were varying opinions on how this should proceed; certain economists wished for a more mixed economy while others wanted the economy to remain mostly socialist. Dubček continued to stress the importance of economic reform proceeding under Communist Party rule.[45]

On 27 June, Ludvík Vaculík a leading author and journalist, published a manifesto titled The Two Thousand Words. It expressed concern about conservative elements within the KSČ and so-called "foreign" forces. Vaculík called on the people to take the initiative in implementing the reform programme.[46] Dubček, the party Presidium, the National Front, and the cabinet denounced this manifesto.[47]

Publications and media

Dubček's relaxation of censorship ushered in a brief period of freedom of speech and the press.[48] The first tangible manifestation of this new policy of openness was the production of the previously hard-line communist weekly Literarni noviny, renamed Literarni listy.[49][50]

The reduction and later complete abolition of the censorship on 4 March 1968 was one of the most important steps towards the reforms. It was for the first time in Czech history the censorship was abolished and it was probably the only reform fully implemented, albeit only for a short period. From the instrument of Party's propaganda media quickly became the instrument of criticism of the regime.[51][52]

Freedom of the press also opened the door for the first honest look at Czechoslovakia's past by Czechoslovakia's people. Many of the investigations centered on the country's history under communism, especially the Joseph Stalin-period.[49] In another television appearance, Goldstucker presented both doctored and undoctored photographs of former communist leaders who had been purged, imprisoned, or executed and thus erased from communist history.[50] The Writer's Union also formed a committee in April 1968, headed by the poet Jaroslav Seifert, to investigate the persecution of writers after the Communist takeover in February 1948 and rehabilitate the literary figures into the Union, bookstores and libraries, and the literary world.[53][54] Discussions on the current state of communism and abstract ideas such as freedom and identity were also becoming more common; soon, non-party publications began appearing, such as the trade union daily Práce (Labour). This was also helped by the Journalists Union, which by March 1968 had already convinced the Central Publication Board, the government censor, to allow editors to receive uncensored subscriptions for foreign papers, allowing for a more international dialogue around the news.[55]

The press, the radio, and the television also contributed to these discussions by hosting meetings where students and young workers could ask questions of writers such as Goldstucker, Pavel Kohout and Jan Procházka and political victims such as Josef Smrkovský, Zdeněk Hejzlar and Gustáv Husák.[56] Television also broadcast meetings between former political prisoners and the communist leaders from the secret police or prisons where they were held.[50] Most importantly, this new freedom of the press and the introduction of television into the lives of everyday Czechoslovak citizens moved the political dialogue from the intellectual to the popular sphere.

Czechoslovak negotiations with the USSR and other Warsaw Pact states

The Soviet leadership at first tried to stop or limit the impact of Dubček's initiatives through a series of negotiations. The Czechoslovak and Soviet Presidiums agreed to bilateral meeting to be held in July 1968 at Čierna nad Tisou, near the Slovak-Soviet border.[57] The meeting was the first time the Soviet Presidium met outside Soviet territory.[24] However, the main agreements were reached at the meetings of the “fours” - Brezhnev, Alexei Kosygin, Nikolai Podgorny, Mikhail Suslov - Dubček, Ludvík Svoboda, Oldřich Černík and Josef Smrkovský.[58]

At the meeting Dubček defended the program of the reformist wing of the KSČ while pledging commitment to the Warsaw Pact and Comecon. The KSČ leadership, however, was divided between vigorous reformers (Josef Smrkovský, Oldřich Černík, Josef Špaček and František Kriegel) who supported Dubček, and conservatives (Vasil Biľak, Drahomír Kolder, and Oldřich Švestka) who represented an anti-reformist stance. Brezhnev decided on compromise. The KSČ delegates reaffirmed their loyalty to the Warsaw Pact and promised to curb "anti-socialist" tendencies, prevent the revival of the Czechoslovak Social Democratic Party, and control the press by the re-imposition of a higher level of censorship.[57] In return the USSR agreed to withdraw their troops (still stationed in Czechoslovakia since the June 1968 maneuvers) and permit 9 September party congress. Dubček appeared on television shortly afterwards reaffirming Czechoslovakia's alliance with the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact.[24]

On 3 August, representatives from the Soviet Union, East Germany, People's Republic of Poland, the Hungarian People's Republic, the People's Republic of Bulgaria and Czechoslovakia met in Bratislava and signed the Bratislava Declaration.[59] The declaration affirmed unshakable fidelity to Marxism–Leninism and proletarian internationalism and declared an implacable struggle against bourgeois ideology and all "antisocialist" forces.[60] The Soviet Union expressed its intention to intervene in a Warsaw Pact country if a bourgeois system was ever established.[61] After the Bratislava conference, Soviet troops left Czechoslovak territory but remained along Czechoslovak borders.[60]

As these talks proved unsatisfactory, the USSR began to consider a military alternative. The Soviet Union's policy of compelling the socialist governments of its satellite states to subordinate their national interests to those of the Eastern Bloc (through military force if needed) became known as the Brezhnev Doctrine.[61]

United States

The United States and NATO largely ignored the situation in Czechoslovakia.[citation needed] Whilst the Soviet Union was concerned about the possibility of losing a regional ally and buffer state, the United States did not publicly seek an alliance with the Czechoslovak government. President Lyndon B. Johnson had already involved the United States in the Vietnam War and was unlikely to be able to drum up support for a conflict in Czechoslovakia. Also, he wanted to pursue an arms control treaty with the Soviets, SALT. He needed a willing partner in Moscow in order to reach such an agreement, and he did not wish to risk that treaty over what was ultimately a minor conflict in Czechoslovakia.[62][63] For these reasons, the United States stated that it would not intervene on behalf of the Prague Spring.[64]

Invasion and intervention

At approximately 11 pm on 20 August 1968,[65] Eastern Bloc armies from four Warsaw Pact countries – the Soviet Union, Bulgaria,[66] Poland and Hungary – invaded Czechoslovakia. That night, 250,000 Warsaw Pact troops and 2,000 tanks entered the country.[3] The total number of invading troops eventually reached 500,000,[citation needed] including 28,000 soldiers[67] of the Polish 2nd Army from the Silesian Military District.[citation needed] Brezhnev wanted the operation to appear multilateral (unlike the Soviet intervention in the Hungarian Revolution of 1956). Nevertheless, the invasion was decidedly dominated by troops from the Soviet Union, which outnumbered other participants five to one, and the Soviet High Command was in charge of the invading armies at all times.[4] The non-Soviet forces took no part in combat.[68] All invading Hungarian troops were withdrawn by 31 October.[69]

Romania did not take part in the invasion,[15] nor did Albania, which subsequently withdrew from the Warsaw Pact over the matter the following month.[16] The participation of East Germany was cancelled just hours before the invasion.[17] The decision for the non-participation of the East German National People's Army in the invasion was made on short notice by Brezhnev at the request of high-ranking Czechoslovak opponents of Dubček who feared much larger Czechoslovak resistance if German troops were present, due to previous experience with the German occupation.[18]

The invasion was well planned and coordinated; simultaneously with the border crossing by ground forces, a Soviet spetsnaz task force of the GRU (Spetsnaz GRU) captured Ruzyne International Airport in the early hours of the invasion. It began with a flight from Moscow which carried more than 100 agents in plain clothes and requested an emergency landing at the airport due to "engine failure". They quickly secured the airport and prepared the way for the huge forthcoming airlift, in which Antonov An-12 transport aircraft began arriving and unloading Soviet Airborne Forces equipped with artillery and light tanks.[70]

As the operation at the airport continued, columns of tanks and motorized rifle troops headed toward Prague and other major centers, meeting almost no resistance. Despite the fact that the Czechoslovak People's Army was one of the most advanced militaries in the Eastern Bloc, it failed to effectively resist the invasion due to its lack of an independent chain of command and the government's fears that it would side with the invaders as the Hungarian People's Army did during the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. The Czechoslovak People's Army was utterly defeated by the Warsaw Pact armies.

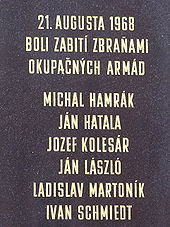

During the attack of the Warsaw Pact armies, 137 Czechs and Slovaks were killed,[12] and hundreds were wounded. Alexander Dubček called upon his people not to resist.[71] The Central Committee, including Dubček, hunkered down at its headquarters as Soviet forces seized control of Prague. Eventually, paratroopers cut the building's telephone lines and stormed the building. Dubček was promptly arrested by the KGB and taken to Moscow along with several of his colleagues.[24] Dubček and most of the reformers were returned to Prague on 27 August, and Dubček retained his post as the party's first secretary until he was forced to resign in April 1969 following the Czechoslovak Hockey Riots.

The invasion was followed by a wave of emigration, largely of highly qualified people, unseen before and stopped shortly after (estimate: 70,000 immediately, 300,000 in total).[72] Western countries allowed these people to immigrate without complications.

Failure to prepare

The Dubček regime took no steps to forestall a potential invasion, despite ominous troop movements by the Warsaw Pact. The Czechoslovak leadership believed that the Soviet Union and its allies would not invade, having believed that the summit at Čierna nad Tisou had smoothed out the differences between the two sides.[73] They also believed that any invasion would be too costly, both because of domestic support for the reforms and because the international political outcry would be too significant, especially with the World Communist Conference coming up in November of that year. Czechoslovakia could have raised the costs of such an invasion by drumming up international support or making military preparations such as blocking roads and ramping up security of their airports, but they decided not to, paving the way for the invasion.[74]

Letter of invitation

Although on the night of the invasion, the Czechoslovak Presidium declared that Warsaw Pact troops had crossed the border without the knowledge of the ČSSR Government, the Eastern Bloc press printed an unsigned request, allegedly by Czechoslovak party and state leaders, for "immediate assistance, including assistance with armed forces".[24][75] At the 14th KSČ Party Congress (conducted secretly, immediately following the intervention), it was emphasized that no member of the leadership had invited the intervention. At the time, a number of commentators believed the letter was fake or non-existent.

In the early 1990s, however, the Russian government gave the new Czechoslovak President, Václav Havel, a copy of a letter of invitation addressed to Soviet authorities and signed by KSČ members Biľak, Švestka, Kolder, Indra, and Kapek. It claimed that "right-wing" media were "fomenting a wave of nationalism and chauvinism, and are provoking an anti-communist and anti-Soviet psychosis". It formally asked the Soviets to "lend support and assistance with all means at your disposal" to save the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic "from the imminent danger of counterrevolution".[76]

A 1992 Izvestia article claimed that candidate Presidium member Antonin Kapek gave Brezhnev a letter at the Soviet-Czechoslovak Čierna and Tisou talks in late July which appealed for "fraternal help". A second letter was supposedly delivered by Biľak to Ukrainian Party leader Petro Shelest during the August Bratislava conference "in a lavatory rendezvous arranged through the KGB station chief".[76] This letter was signed by the same five as Kapek's letter, mentioned above.

Internal plot

Long before the invasion, planning for a coup was undertaken by Indra, Kolder and Biľak, among others, often at the Soviet embassy and at the Party recreation centre at Orlík Dam.[76] When these men had managed to convince a majority of the Presidium (six of eleven voting members) to side with them against Alexander Dubček's reformists, they asked the USSR to launch a military invasion. The USSR leadership was even considering waiting until the 26 August Slovak Party Congress, but the Czechoslovak conspirators "specifically requested the night of the 20th".[76]

The plan was to unfold as follows. A debate would unfold in response to the Kašpar report on the state of the country, during which conservative members would insist that Dubček present two letters he had received from the USSR; letters which listed promises he had made at the Čierna and Tisou talks but had failed to keep. Dubček's concealment of such important letters, and his unwillingness to keep his promises would lead to a vote of confidence which the now conservative majority would win, seizing power, and issue a request for Soviet assistance in preventing a counterrevolution. It was this formal request, drafted in Moscow, which was published in Pravda on 22 August without the signatories. All the USSR needed to do was suppress the Czechoslovak military and any violent resistance.[77]

With this plan in mind, the 16 to 17 August Soviet Politburo meeting unanimously passed a resolution to "provide help to the Communist Party and people of Czechoslovakia through military force".[77][4] At an 18 August Warsaw Pact meeting, Brezhnev announced that the intervention would go ahead on the night of 20 August, and asked for "fraternal support", which the national leaders of Bulgaria, East Germany, Hungary, and Poland duly offered.

Failure of the plot

The coup, however, did not go according to plan. Kolder intended to review the Kašpar report early on in the meeting, but Dubček and Špaček, suspicious of Kolder, adjusted the agenda so the upcoming 14th Party Congress could be covered before any discussion on recent reforms or Kašpar's report. Discussion of the Congress dragged on, and before the conspirators had a chance to request a confidence vote, early news of the invasion reached the Presidium.[75]

An anonymous warning was transmitted by the Czechoslovak Ambassador to Hungary, Jozef Púčik, approximately six hours before Soviet troops crossed the border at midnight.[75] When the news arrived, the solidarity of the conservative coalition crumbled. When the Presidium proposed a declaration condemning the invasion, two key members of the conspiracy, Jan Pillar and František Barbírek, switched sides to support Dubček. With their help, the declaration against the invasion won with a 7:4 majority.[76]

Moscow Protocol

By the morning of 21 August, Dubček and other prominent reformists had been arrested and were later flown to Moscow. There they were held in secret and interrogated for days.[78]

The conservatives asked Svoboda to create an "emergency government" but since they had not won a clear majority of support, he refused. Instead, he and Gustáv Husák traveled to Moscow on 23 August to insist Dubček and Černík should be included in a solution to the conflict. After days of negotiations, all members of the Czechoslovak delegation (including all the highest-ranked officials President Svoboda, First Secretary Dubček, Prime Minister Černík and Chairman of the National Assembly Smrkovský) but one (František Kriegel)[79] accepted the "Moscow Protocol", and signed their commitment to its fifteen points. The Protocol demanded the suppression of opposition groups, the full reinstatement of censorship, and the dismissal of specific reformist officials.[77] It did not, however, refer to the situation in the ČSSR as "counterrevolutionary" nor did it demand a reversal of the post-January course.[77]

Reactions in Czechoslovakia

Popular opposition was expressed in numerous spontaneous acts of nonviolent resistance. In Prague and other cities throughout the republic, Czechs and Slovaks greeted Warsaw Pact soldiers with arguments and reproaches. Vladimir Bogdanovich Rezun, then a junior officer who led a Soviet Tank column during the invasion, was given absurd information from his commanders about how the people of Czechoslovakia would welcome them as their "Liberators", and were instead attacked by angry crowds of people who threw stones, eggs, tomatoes, and apples upon crossing into Slovakia.[80] Every form of assistance, including the provision of food and water, was denied to the invaders. In an opposite case of subterfuge, Rezun recalled how local townspeople quietly opened the gates of the Czech breweries and spirit factories for the enlisted Soviet soldiers, making entire units inebriated and causing significant disruptions to the fury of the Soviet commanders.[81] Signs, placards, and graffiti drawn on walls and pavements denounced the invaders, the Soviet leaders, and suspected collaborationists. Pictures of Dubček and Svoboda appeared in the streets. Citizens gave wrong directions to soldiers and even removed street signs (except for those giving the direction back to Moscow).[82] Against organizers, perpetrators, and European leaders who pushed for the invasions, Czechoslovakians demonstrated their anger, expressed through art, songs, and media. One of the most famous examples can be seen in the case of Walter Ulbricht, the East German leader who heavily pushed for the invasion. He ordered the East German military to prepare two NVA divisions, comprising over 16,000 troops, for the invasion, but the Soviet Union did not allow him to deploy them, for fear of reawakening memories of the 1939 German invasion.[83] Despite the NVA troops being halted, anger and disdain for collaborators and advocates such as Ulbricht remained strong. One poster stated, “German soldiers go home and liquidate Ulbricht, who is a new Hitler! Your people do not agree with your actions!”[84]

Initially, some civilians tried to argue with the invading troops, but this met with little or no success. After the USSR used photographs of these discussions as proof that the invasion troops were being greeted amicably, secret Czechoslovak broadcasting stations discouraged the practice, reminding the people that "pictures are silent."[85] The protests in reaction to the invasion lasted only about seven days. Explanations for the fizzling of these public outbursts mostly center on demoralization of the population, whether from the intimidation of all the enemy troops and tanks or from being abandoned by their leaders. Many Czechoslovaks saw the signing of the Moscow Protocol as treasonous.[86] Another common explanation is that, due to the fact that most of Czech society was middle class, the cost of continued resistance meant giving up a comfortable lifestyle, which was too high a price to pay.[87]

The generalised resistance caused the Soviet Union to abandon its original plan to oust the First Secretary. Dubček, who had been arrested on the night of 20 August, was taken to Moscow for negotiations. It was agreed that Dubček would remain in office and a program of moderate reform would continue.

On 19 January 1969, student Jan Palach set himself on fire in Wenceslas Square in Prague to protest the renewed suppression of free speech.

Finally, on 17 April 1969, Dubček was replaced as First Secretary by Gustáv Husák, and a period of "Normalization" began. Pressure from the Soviet Union pushed politicians to either switch loyalties or simply give up. In fact, the very group that voted in Dubček and put the reforms in place were mostly the same people who annulled the program and replaced Dubček with Husák. Husák reversed Dubček's reforms, purged the party of its liberal members, and dismissed the professional and intellectual elites who openly expressed disagreement with the political turnaround from public offices and jobs. Many of those purged would later become the dissidents of Czechoslovak underground culture, active in Charter 77 and related movements that eventually met success in the Velvet Revolution.

Reactions in other Warsaw Pact countries

Soviet Union

For your freedom and ours

On 25 August, at the Red Square, eight protesters carried banners with anti-invasion slogans. The demonstrators were arrested and later punished, as the protest was dubbed "anti-Soviet".[88][89]

One unintended consequence of the invasion was that many within the Soviet State security apparatus and Intelligence Services were shocked and outraged at the invasion and several KGB/GRU defectors and spies such as Oleg Gordievsky, Vasili Mitrokhin, and Dmitri Polyakov have pointed out the 1968 invasion as their motivation for cooperating with the Western Intelligence agencies.

Poland

In the People's Republic of Poland, on 8 September 1968, Ryszard Siwiec immolated himself in Warsaw during a harvest festival at the 10th-Anniversary Stadium in protest against the Warsaw Pact's invasion of Czechoslovakia and the totalitarianism of the Communist regime.[90][91] Siwiec did not survive.[90] After his death, Soviets and Polish communists attempted to discredit his act by claiming that he was psychologically ill and mentally unstable.

Romania

A more pronounced effect took place in the Socialist Republic of Romania, which did not take part in the invasion. Nicolae Ceauşescu, who was already a staunch opponent of Soviet influence and had previously declared himself on Dubček's side, held a public speech in Bucharest on the day of the invasion, depicting Soviet policies in harsh terms. This response consolidated Romania's independent voice in the next two decades, especially after Ceauşescu encouraged the population to take up arms in order to meet any similar maneuver in the country: he received an enthusiastic initial response, with many people, who were by no means Communist, willing to enroll in the newly formed paramilitary Patriotic Guards.[citation needed]

East Germany

In the German Democratic Republic, the invasion aroused discontent mostly among young people who had hoped that Czechoslovakia would pave the way for a more liberal socialism.[92] However, isolated protests were quickly stopped by the Volkspolizei and Stasi.[93] The official government newspaper Neues Deutschland published an article before the invasion began, which falsely claimed that the Czechoslovak Presidium had ousted Dubcek and that a new "revolutionary" provisional government had Warsaw Pact military assistance.[24] Despite NVA troops being withheld from participating in the full-scale invasion, the East German state, specifically through media, preserved the illusion that East Germany played an important and "equal" role compared to other Eastern Bloc nations in the invasion. Until the fall of the Berlin Wall, the SED (ruling party that was in power for the entirety of East Germany's existence) not only failed to counter or dispute Western media's narratives about the role of the NVA in the invasion, but pushed the narrative that the NVA played a crucial and equal role as its Eastern Bloc allies. In 1985, the official East German military publishing house in Berlin published an article asserting that the NVD fought alongside their "fraternal" armies as equals in suppressing the "counterrevolution."[94]

Albania

The People's Republic of Albania responded in an opposite fashion. It was already feuding with Moscow over suggestions that Albania should focus on agriculture to the detriment of industrial development, and it also felt that the Soviet Union had become too liberal since the death of Joseph Stalin, as well as with Yugoslavia (which by that time was regarded as a threatening neighbor by Albania), which it was branding as "imperialist" in its propaganda. The invasion served as the tipping point, and in September 1968, Albania formally withdrew from the Warsaw Pact.[16] The economic fallout from this move was mitigated somewhat by a strengthening of Albanian relations with the People's Republic of China, which was also on increasingly strained terms with the Soviet Union.

Reactions around the world

On the night of the invasion, Canada, Denmark, France, Paraguay, the United Kingdom and the United States all requested a session of the United Nations Security Council.[95] The night of August 20, movie theaters in Prague showed news reels of a meeting between Brezhnev and Dubček. However the Warsaw Pact had amassed at the Czech border, and invaded overnight (August 20–21). That afternoon, on August 21, the council met to hear the Czechoslovak Ambassador Jan Mužík denounce the invasion. Soviet Ambassador Jacob Malik insisted the Warsaw Pact actions were those of "fraternal assistance" against "antisocial forces".[95] Many of the invading soldiers told the Czechs that they were there to "liberate" them from West German and other NATO hegemony. The next day, several countries suggested a resolution condemning the intervention and calling for immediate withdrawal. US Ambassador George Ball suggested that "the kind of fraternal assistance that the Soviet Union is according to Czechoslovakia is exactly the same kind that Cain gave to Abel".[95]

Ball accused Soviet delegates of filibustering to put off the vote until the occupation was complete. Malik continued to speak, ranging in topics from US exploitation of Latin America's raw materials to statistics on Czech commodity trading.[95] Eventually, a vote was taken. Ten members ( 4 with veto power) supported the motion; Algeria, India, and Pakistan abstained; the USSR (with veto power) and Hungary opposed it. Canadian delegates immediately introduced another motion asking for a UN representative to travel to Prague and work for the release of the imprisoned Czechoslovak leaders.[95] Malik accused Western countries of hypocrisy, asking "who drowned the fields, villages, and cities of Vietnam in blood?"[95] By 26 August, another vote had not taken place, but a new Czechoslovak representative requested the whole issue be removed from the Security Council's agenda.[citation needed]

The invasion occurred simultaneously with the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, and multiple political factions seized upon the events as a symbol. Student activists such as Abbie Hoffman and progressives such as Ralph Yarborough and Eugene McCarthy compared the repression of the Prague Spring to repression of Western student movements such as in the 1968 Chicago riots, with Hoffman calling Chicago "Czechago." On the other hand, anti-Communists such as John Connally used the incident to urge tougher relations with the Soviet Union and a renewed commitment to the Vietnam War.[24]

Although the United States insisted at the UN that Warsaw Pact aggression was unjustifiable, its position was weakened by its own actions. Only three years earlier, US delegates to the UN had insisted that the overthrow of the leftist government of the Dominican Republic, as part of Operation Power Pack, was an issue to be worked out by the Organization of American States (OAS) without UN interference. When UN Secretary-General U Thant called for an end to the bombing of Vietnam, the Americans questioned why he didn't similarly intervene on the matter of Czechoslovakia, to which he responded that "if Russians were bombing and napalming the villages of Czechoslovakia" he might have called for an end to the occupation.[95]

The United States government sent Shirley Temple Black, the famous child movie star, who became a diplomat in later life, to Prague in August 1968 to prepare to become the first United States Ambassador to a post-Communist Czechoslovakia. She attempted to form a motorcade for evacuation of trapped Westerners. Two decades later, when the Warsaw Pact forces left Czechoslovakia in 1989, Temple Black was recognized as the first American ambassador to a democratic Czechoslovakia. In addition to her own personnel, an attempt was made to evacuate a group of 150 American high school students stuck in the invasion who had been on a summer abroad trip studying Russian in the (then) USSR and affiliated countries. They were eventually evacuated by train to Vienna, smuggling their two Czech tour guides across the border who settled in New York.[96]

In Finland, a neutral country under some Soviet political influence at that time, the occupation caused a major scandal.[97]

The People's Republic of China objected furiously to the so-called Brezhnev Doctrine, which declared the Soviet Union alone had the right to determine what nations were properly Communist and could invade those Communist nations whose communism did not meet the Kremlin's approval.[98] Mao Zedong saw the Brezhnev doctrine as the ideological justification for a would-be Soviet invasion of China and launched a massive propaganda campaign condemning the invasion of Czechoslovakia, despite his own earlier opposition to the Prague Spring.[99] Speaking at a banquet held at the Romanian Embassy in Beijing on 23 August 1968, the Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai denounced the Soviet Union for "fascist politics, great power chauvinism, national egoism and social imperialism", going on to compare the invasion of Czechoslovakia to the Vietnam War and more pointedly to the policies of Adolf Hitler towards Czechoslovakia in 1938–39.[98] Zhou ended his speech with a barely veiled call for the people of Czechoslovakia to wage guerrilla war against the Red Army.[98] Along with the subsequent Sino-Soviet border conflict at Zhenbao island, the invasion of Czechoslovakia contributed to Chinese policy-makers' fears of Soviet invasion, leading them to accelerate the Third Front campaign, which had slowed during the Cultural Revolution.[100]

Communist parties worldwide

Reactions from communist parties outside the Warsaw Pact were generally split. Italian and Spanish eurocommunist parties denounced the occupation,[101] and even the Communist Party of France, which had pleaded for conciliation, expressed its disapproval about the Soviet intervention.[102] The Communist Party of Greece (KKE) suffered a major split over the internal disputes over the Prague Spring,[101] with the pro-Czech faction breaking ties with the Soviet leadership and founding the Eurocommunist KKE Interior. The Eurocommunist leadership of the Communist Party of Finland denounced the invasion as well, thereby however fueling the internal disputes with its pro-Soviet minority faction, which eventually led to the party's disintegration.[103] Others, including the Portuguese Communist Party, the South African Communist Party and the Communist Party USA, however supported the Soviet position.[101]

Christopher Hitchens recapitulated the repercussions of the Prague Spring to western Communism in 2008: "What became clear, however, was that there was no longer something that could be called the world Communist movement. It was utterly, irretrievably, hopelessly split. The main spring had broken. And the Prague Spring had broken it."[101]

Normalization (1969–1971)

In the history of Czechoslovakia, normalization (Czech: normalizace, Slovak: normalizácia) is a name commonly given to the period 1969–87. It was characterized by initial restoration of the conditions prevailing before the reform period led by Dubček, first of all, the firm rule of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and subsequent preservation of this new status quo.

"Normalization" is sometimes used in a narrower sense to refer only to the period 1969 to 1971.

The official ideology of normalization is sometimes called Husakism after the Czechoslovak leader Gustáv Husák.

Revoking or modifying the reforms and removing the reformers

When Husák replaced Dubček as leader of the KSČ in April 1969, his regime quickly acted in order to "normalize" the country's political situation. The chief objectives of Husák's normalization were the restoration of firm party rule and the reestablishment of Czechoslovakia's status as a committed member of the socialist bloc. The normalization process involved five interrelated steps:

- consolidate the Husák leadership and remove the reformers from leadership positions;

- revoke or modify the laws which were enacted by the reform movement;

- reestablish centralized control over the economy;

- reinstate the power of police authorities; and

- expand Czechoslovakia's ties with other socialist nations.

Within a week after he assumed power, Husák began to consolidate his leadership by ordering extensive purges of the reformers who were still occupying key positions in the mass media, judiciary, social and mass organizations, lower party organs, and, finally, the highest levels of the KSČ. In the fall of 1969, twenty-nine liberals on the Central Committee of the KSČ were replaced by conservatives. Among the liberals ousted was Dubček, who was dropped from the Presidium (the following year Dubček was expelled from the party; he subsequently became a minor functionary in Slovakia, where he still lived in 1987). Husák also consolidated his leadership by appointing potential rivals to the new government positions which were created as a result of the 1968 Constitutional Law of Federation (which created the Czech Socialist Republic and the Slovak Socialist Republic).

Once it had consolidated its power, the regime quickly moved to implement other normalization policies. In the two years which followed the invasion, the new leadership revoked some reformist laws (such as the National Front Act and the Press Act) and simply did not enforce others. It returned economic enterprises, which had been given substantial independence during the Prague Spring, to centralized control through contracts which were based on central planning and production quotas. It reinstated extreme police control, a step that was reflected in the harsh treatment of demonstrators who attempted to mark the first anniversary of the August intervention.

Finally, Husák stabilized Czechoslovakia's relations with its allies by arranging frequent intrabloc exchanges and visits and redirecting Czechoslovakia's foreign economic ties towards greater involvement with socialist nations.

By May 1971, Husák could report to the delegates who were attending the officially sanctioned Fourteenth Party Congress that the process of normalization had been satisfactorily completed and he could also report that Czechoslovakia was ready to proceed towards higher forms of socialism.

Later reactions and revisionism

The first government to offer an apology was the government of Hungary, on 11 August 1989. The Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party published its opinion on the fundamentally wrong decision to invade Czechoslovakia. In 1989, on the 21st anniversary of the military intervention, the House of the National Assembly of Poland adopted a resolution condemning the armed intervention. Another resolution was issued by the People's Assembly of East Germany on 1 December 1989, when it apologized for its involvement in the military intervention to the Czechoslovak people. Another apology was issued by Bulgaria on 2 December 1989.[104]

On 4 December 1989, Mikhail Gorbachev and other Warsaw Pact leaders drafted a statement which called the 1968 invasion a mistake. The statement, released by the Soviet news agency Tass, said that sending in troops constituted "interference in the internal affairs of a sovereign Czechoslovakia and it must be condemned."[105] The Soviet government also said that the 1968 action was "an unbalanced, inadequate approach, an interference in the affairs of a friendly country".[106] Gorbachev later said that Dubček "believed that he could build socialism with a human face. I have only a good opinion of him."[29]

The invasion was also condemned by the newly appointed Russian President Boris Yeltsin ("We condemn it as an aggression, as an attack on a sovereign, stand-up state as interference in its internal affairs").[104] During a state visit to Prague, on 1 March 2006, Vladimir Putin said that the Russian Federation bore moral responsibility for the invasion, referring to his predecessor Yeltsin's description of 1968 as an act of aggression: "When President Yeltsin visited the Czech Republic in 1993 he was not speaking just for himself, he was speaking for the Russian Federation and for the Russian people. Today, not only do we respect all agreements signed previously – we also share all the evaluations that were made at the beginning of the 1990s... I must tell you with absolute frankness – we do not, of course, bear any legal responsibility. But the moral responsibility is there, of course".[107]

Dubček stated: "My problem was not having a crystal ball to foresee the Russian invasion. At no point between January and August 20, in fact, did I believe that it would happen."[108]

On 23 May 2015, the Russian state television channel Russia-1 aired Warsaw Pact: Declassified Pages, a documentary that presented the invasion as a protective measure against a NATO coup.[109][110][111] The film was widely condemned as political propaganda.[112] Slovakia's Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that the film "attempts to rewrite history and to falsify historical truths about such a dark chapter of our history".[113] František Šebej, the Slovak chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the National Council, stated that "They describe it as brotherly help aimed to prevent an invasion by NATO and fascism. Such Russian propaganda is hostile toward freedom and democracy, and also to us."[114] Czech President Miloš Zeman stated that "Russian TV lies, and no other comment that this is just a journalistic lie, can not be said".[115] Czech Foreign Minister Lubomír Zaorálek said that the film "grossly distorts" the facts.[111][116] Russian ambassador to the Czech Republic, Sergei Kiselyov, has distanced himself from the film and stated that the documentary does not express the official position of the Russian government.[117] One of the most popular Russian online newspapers, Gazeta.Ru, has described the document as biased and revisionist, which harms Russia.[118]

See also

- History of Czechoslovakia (1948–1989)

- Ota Šik

- Prague Spring

- Hungarian Revolution of 1956

- 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

- List of conflicts related to the Cold War

- Foreign interventions by the Soviet Union

- Proletarian internationalism

- Civilian-based defense

References

- ^ Invasion cancelled, troops prepared, part of the executive staff

- ^ Rea, Kenneth "Peking and the Brezhnev Doctrine". Asian Affairs. 3 (1975) p. 22.

- ^ A Look Back ... The Prague Spring & the Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia Archived 29 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved on 11 June 2016.

- ^ a b Washington Post, (Final Edition), 21 August 1998, p. A11

- ^ a b c Van Dijk, Ruud, ed. (2008). Encyclopedia of the Cold War. Routledge. p. 718. ISBN 978-0203880210.

- ^ Invaze vojsk Varšavské smlouvy do Československa 21. srpna 1968. armyweb.cz. Retrieved on 11 June 2016.

- ^ Šatraj, Jaroslav. "Operace Dunaj a oběti na straně okupantů". Cтрановедение России (Reálie Ruska). Západočeská univerzita v Plzni. Archived from the original on 8 January 2008. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ Minařík, Pavel; Šrámek, Pavel. "Čs. armáda po roce 1945". Vojenstvi.cz. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ "The Soviet War in Afghanistan: History and Harbinger of Future War". Ciaonet.org. 27 April 1978. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ Jak zemřeli vojáci armád při invazi '68: Bulhara zastřelili Češi, Sověti umírali na silnicích. Hospodářské noviny IHNED.cz. Retrieved on 11 June 2016.

- ^ Skomra, Sławomir. "Brali udział w inwazji na Czechosłowację. Kombatanci?" (in Polish). Agora SA. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ Gigov, Lyubomir (27 August 2024). "Bulgaria's Role in 1968 Invasion of Czechoslovakia". Bulgarian News Agency. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ a b c Fraňková, Ruth (18 August 2017). "Historians pin down number of 1968 invasion victims". radio.cz. Archived from the original on 26 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ a b "August 1968 – Victims of the Occupation". ustrcr.cz. Ústav pro studium totalitních režimů. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- ^ Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia Archived 31 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine. European Network Remembrance and Solidarity. Retrieved on 11 June 2016.

- ^ a b Soviet foreign policy since World .... Google Books. Retrieved on 23 June 2011.

- ^ a b c "1955: Communist states sign Warsaw Pact". BBC News. 14 May 1955. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ a b Stolarik, M. Mark (2010). The Prague Spring and the Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia, 1968: Forty Years Later. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. pp. 137–164. ISBN 9780865167513.

- ^ a b NVA-Truppen machen Halt an der tschechoslowakischen Grenze radio.cz. Retrieved on 12 June 2016.

- ^ Williams (1997), p. 170

- ^ Williams (1997), p. 7

- ^ Czech radio broadcasts 18–20 August 1968

- ^ Karen Dawisha (1981). "The 1968 Invasion of Czechoslovakia: Causes, Consequences, and Lessons for the Future" in Soviet-East European Dilemmas: Coercion, Competition, and Consent ed. Karen Dawisha and Philip Hanson. New York: Homs and Meier Publishers Inc.[page needed][ISBN missing]

- ^ Jiri Valenta, Soviet Intervention in Czechoslovakia, 1968: Anatomy of a Decision (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979) 3

- ^ a b c d e f g Kurlansky, Mark. (2004). 1968 : the year that rocked the world (1st ed.). New York: Ballantine. ISBN 0-345-45581-9. OCLC 53929433.

- ^ Jiri Valenta, "From Prague to Kabul," International Security 5, (1980), 117

- ^ Mark Kramer. Ukraine and the Soviet-Czechoslovak Crisis of 1968 (part 2) Archived 19 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. New Evidence from the Ukrainian Archives. Cold War International History Project Bulletin, Issue 14/15. 2004. pp. 273–275.

- ^ Hignett, Kelly (27 June 2012). "Dubcek's Failings? The 1968 Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia".

- ^ TismaneanuI, Vladimir, ed. (2011). "Crisis, Illusion and Utopia". Promises of 1968: Crisis, Illusion and Utopia (NED – New edition, 1 ed.). Central European University Press. ISBN 978-6155053047. JSTOR 10.7829/j.ctt1281xt.[page needed]

- ^ a b "Czech Republic: 1968 Viewed From The Occupiers' Perspective". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 9 April 2008.

- ^ Jiri Valenta, Soviet Intervention in Czechoslovakia, 1968: Anatomy of a Decision (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991).

- ^ Mark Stolarik, The Prague Spring and the Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia, 1968: Forty Years Later (Mundelein, Ill: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2010).

- ^ Valenta (Fn. 7) 17

- ^ Ello (1968), pp. 32, 54

- ^ Von Geldern, James; Siegelbaum, Lewis. "The Soviet-led Intervention in Czechoslovakia". Soviethistory.org. Archived from the original on 17 August 2009. Retrieved 7 March 2008.

- ^ Hochman, Dubček (1993)

- ^ Dubček, Alexander (10 April 1968). Kramer, Mark; Moss, Joy (eds.). "Akční program Komunistické strany Československa". Action Program (in Czech). Translated by Tosek, Ruth. Rudé právo. pp. 1–6. Archived from the original on 6 May 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2008.

- ^ a b Judt (2005), p. 441

- ^ a b c d e f g Ello (1968), pp. 7–9, 129–31

- ^ Derasadurain, Beatrice. "Prague Spring". thinkquest.org. Archived from the original on 14 November 2007. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ^ Kusin (2002), pp. 107–122

- ^ "The Prague Spring, 1968". Library of Congress. 1985. Retrieved 5 January 2008.

- ^ Williams (1997), p. 156

- ^ Williams (1997), p. 164

- ^ Williams (1997), pp. 18–22

- ^ Vaculík, Ludvík (27 June 1968). "Two Thousand Words". Literární listy.

- ^ Mastalir, Linda (25 July 2006). "Ludvík Vaculík: a Czechoslovak man of letters". Radio Prague. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ^ Williams, Tieren (1997). The Prague Spring and Its Aftermath: Czechoslovak Politics, 1968–1970. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 67.

- ^ a b Williams, p. 68

- ^ a b c Bren, Paulina (2010). The Greengrocer and His TV: The Culture of Communism after the 1968 Prague Spring. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 23ff. ISBN 978-0-8014-4767-9.

- ^ Vondrová, Jitka (25 June 2008). "Pražské Jaro 1968". Akademický bulletin (in Czech). Akademie věd ČR. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ Hoppe, Jiří (6 August 2008). "Co je Pražské jaro 1968?". iForum (in Czech). Charles University. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ Golan, Galia (1973). Cambridge Russian, Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies. Reform Rule in Czechoslovakia: The Dubček Era, 1968–1969. Vol. 11. Cambridge: CUP Archive, p. 10

- ^ Holy, p. 119

- ^ Golan, p. 112

- ^ Williams, p. 69

- ^ a b "1968: Bilateral meeting anticipated Soviet invasion" aktualne.cz. Retrieved on 11 June 2016.

- ^ Jiri Valenta (1979). Soviet Intervention in Czechoslovakia, 1968. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 151. ISBN 0-8018-4297-2.

- ^ "The Bratislava Declaration, August 3, 1968" Navratil, Jaromir. Archived 14 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine "The Prague Spring 1968". Hungary: Central European Press, 1998, pp. 326–329 Retrieved on 4 March 2013.

- ^ a b The Bratislava Meeting. stanford.edu. Archived 9 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 11 June 2016.

- ^ a b Ouimet, Matthew J. (2003). The Rise and Fall of the Brezhnev Doctrine in Soviet Foreign Policy. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-8078-2740-6.

- ^ Dawisha (Fn. 6) 10

- ^ Kurlander, David (17 September 2020). "A Shattering Moment: LBJ's Last Hope and The End of the Prague Spring". Cafe. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia - ABC News - August 21, 1968 Archived February 2, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Russians march into Czechoslovakia". The Times. London. 21 August 1968. Archived from the original on 11 September 2008. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ Czechoslovakia 1968 "Bulgarian troops". Google Books. Retrieved on 23 June 2011.

- ^ Jerzy Lukowski, Hubert Zawadzki: A Concise History of Poland, 2006. Google Books (17 July 2006). Retrieved on 23 June 2011.

- ^ Tismaneanu, Vladimir, ed. (2011). Promises of 1968: Crisis, Illusion, and Utopia. Central European University Press. p. 358. ISBN 9786155053047.

- ^ Czechoslovakia 1968 "Hungarian troops". Google Books (22 October 1968). Retrieved on 23 June 2011.

- ^ "GRU, Alpha and Vympel: Russia's most famous covert operators". rbth.com. 18 June 2017.

- ^ Williams (1997), p. 158

- ^ "Day when tanks destroyed Czech dreams of Prague Spring" ("Den, kdy tanky zlikvidovaly české sny Pražského jara") at Britské Listy (British Letters). Britskelisty.cz. Retrieved on 23 June 2011.

- ^ Jiri Valenta, "Could the Prague Spring Have Been Saved" Orbis 35 (1991) 597

- ^ Valenta (Fn. 23) 599.

- ^ a b c H. Gordon Skilling, Czechoslovakia's Interrupted Revolution, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976)

- ^ a b c d e Kieran Williams, "The Prague Spring and its aftermath: Czechoslovak politics 1968–1970," (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

- ^ Vladimir Kusin, From Dubcek to Charter 77 (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1978) p. 21

- ^ "The Man Who Said "No" to the Soviets". 21 August 2015.

- ^ Suvorov 162

- ^ Suvorov 185

- ^ John Keane, Vaclav Havel: A Political Tragedy in Six Acts (New York: Basic Books, 2000) 213

- ^ Mark Stolarik, The Prague Spring and the Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia, 1968: Forty Years Later (Mundelein, Ill: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2010).

- ^ Pabel, Hilmar. “Poster Protesting the Invasion of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic by Warsaw Pact Troops (August 21, 1968).” Ghdi Image. https://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/sub_image.cfm?image_id=2495.

- ^ Bertleff, Erich. Mit bloßen Händen – der einsame Kampf der Tschechen und Slowaken 1968. Verlag Fritz Molden.

- ^ Alexander Dubcek, "Hope Dies Last" (New York: Kodansha International, 1993) 216

- ^ Williams (Fn. 25) 42

- ^ Letter by Yuri Andropov to Central Committee about the demonstration, 5 September 1968, in the Vladimir Bukovsky's archive, (PDF, faximile, in Russian), JHU.edu Archived 8 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Andropov to the Central Committee. The Demonstration in Red Square Against the Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia. 20 September 1968, at Andrei Sakharov's archive, in Russian and translation into English, Yale.edu Archived 12 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b (in English) "Hear My Cry – Maciej Drygas". culture.pl. June 2007. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ^ (in English) "Czech Prime Minister Mirek Topolánek honoured the memory of Ryszard Siwiec". www.vlada.cz. Press Department of the Office of Czech Government. Retrieved 22 August 2008.

- ^ Allinson, Mark (2000). Politics and Popular Opinion in East Germany, 1945–68. Manchester University Press. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-0719055546.

- ^ Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung: Die versäumte Revolte: Die DDR und das Jahr 1968 – Ideale sterben langsam (in German). Bpb.de (2 March 2011). Retrieved on 23 June 2011.

- ^ Mark Stolarik, The Prague Spring and the Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia, 1968: Forty Years Later (Mundelein, Ill: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2010).

- ^ a b c d e f g Franck, Thomas M. (1985). Nation Against Nation: What Happened to the U.N. Dream and What the U.S. Can Do About It. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503587-2.

- ^ "International; Prague's Spring Into Capitalism" by Lawrence E. Joseph at The. New York Times (2 December 1990). Retrieved on 23 June 2011.

- ^ Jutikkala, Eino; Pirinen, Kauko (2001). Suomen historia (History of Finland). ISBN 80-7106-406-8.

- ^ a b c Rea, Kenneth "Peking and the Brezhnev Doctrine". Asian Affairs. 3 (1975) p. 22.

- ^ Rea, Kenneth "Peking and the Brezhnev Doctrine". Asian Affairs. 3 (1975)p. 22.

- ^ Meyskens, Covell F. (2020). Mao's Third Front: The Militarization of Cold War China. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 150. doi:10.1017/9781108784788. ISBN 978-1-108-78478-8. OCLC 1145096137. S2CID 218936313.

- ^ a b c d Hitchens, Christopher (25 August 2008). "The Verbal Revolution. How the Prague Spring broke world communism's main spring". Slate. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Devlin, Kevin. "Western CPs Condemn Invasion, Hail Prague Spring". Blinken Open Society Archives. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ Tuomioja, Erkki (2008). "The Effects of the Prague Spring in Europe". Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ a b Raduševič, Mirko. "Gorbačov o roce 1968: V životě jsem nezažil větší dilema". Literární noviny (in Czech). Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ Imse, Ann (5 December 1989). "Soviet, Warsaw Pact Call 1968 Invasion of Czechoslovakia a Mistake With AM-Czechoslovakia, Bjt". Associated Press News. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ Schodolski, Vincent J. (5 December 1989). "Soviets: Prague Invasion Wrong". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018.

- ^ Cameron, Rob (2 March 2006). "Putin: Russia bears "moral responsibility" for 1968 Soviet invasion". Radio Prague. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ Alexander Dubcek, "Hope Dies Last" (New York: Kodansha International, 1993) 128

- ^ "Russian TV doc on 1968 invasion angers Czechs and Slovaks". BBC News. 1 June 2015.

- ^ "Russian Documentary On 'Helpful' 1968 Invasion Angers Czechs". Radio Free Europe. 1 June 2015.

- ^ a b Mortkowitz Bauerova, Ladka; Ponikelska, Lenka (1 June 2015). "Russian 1968 Prague Spring Invasion Film Angers Czechs, Slovaks". bloomberg.com.

- ^ Bigg, Claire. "4 distortions about Russian history that the Kremlin is now promoting". Business Insider. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Statement of the Speaker of the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs of the Slovak Republic on the documentary film of the Russian television about the 1968 invasion". Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs of the Slovak Republic. 31 May 2015. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

- ^ "Fico to return to Moscow to meet Putin, Medvedev". Czech News Agency. Prague Post. 1 June 2015. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ "Zeman: Ruská televize o roce 1968 lže, invaze byla zločin". Novinky.cz (in Czech). Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ "Ministr Zaorálek si předvolal velvyslance Ruské federace". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic (in Czech). 1 June 2015. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ "Zaorálek k sankčnímu seznamu: Takové zacházení s Čechy odmítáme". Česká televize. 1 June 2015 (in Czech).

- ^ "Neobjektivita škodí Rusku, napsal k dokumentu o srpnu 1968 ruský deník". Novinky.cz (in Czech).

Further reading

- Bischof, Günter; Karner, Stefan; Ruggenthaler, Peter, eds. (2010). The Prague Spring and the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. The Harvard Cold War studies book series. Lanham, Md: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-4304-9. OCLC 436358434.

- Suvorov, Viktor (1981). The liberators. London: H. Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-241-10675-4.

- Williams, Kieran (2011). "Civil Resistance in Czechoslovakia: From Soviet Invasion to 'Velvet Revolution', 1968–89". In Roberts, Adam; Garton Ash, Timothy (eds.). Civil resistance and power politics: the experience of non-violent action from Gandhi to the present. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 110–26. ISBN 978-0-19-969145-6.

- Windsor, Philip (1969). Windsor, Philip; Roberts, Adam (eds.). Czechoslovakia 1968: Reform, repression and resistance. An ISS paperback. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-1498-5.

External links

Media related to Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia at Wikimedia Commons- "Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia": Collection of archival documents on www.DigitalArchive.org

- Project 1968–1969, page dedicated to documenting the invasion, created by the Totalitarian Regime Study Institute

- Breaking news coverage of the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia as heard on WCCO Radio (Minneapolis, MN) and CBS Radio as posted on RadioTapes.com

- The short film Russian Invasion of Czechoslovakia (1968) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The short film Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia (1968) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.