Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia

| Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War II | |

Polish victims of a massacre committed by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army in the village of Lipniki, Wołyń (Volhynia), 1943 | |

| Location | Volhynia Eastern Galicia Polesie Lublin region |

| Date | 1943–1945 |

| Target | Poles |

Attack type | Massacre, ethnic cleansing, considered a genocide in Poland |

| Deaths | 60,000[1]–120,000 Poles[2] 340 Czechs[3] |

| Perpetrators | Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, Ukrainian Insurgent Army, Mykola Lebed, Roman Shukhevych |

| Motive | Anti-Polonism,[4] Anti-Catholicism,[5] Ukrainisation[3] |

The Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia (Polish: rzeź wołyńsko-galicyjska, lit. 'Volhynian-Galician slaughter'; Ukrainian: Волинсько-Галицька трагедія, romanized: Volynsʹko-Halytsʹka trahediya, lit. 'Volhynian-Galician tragedy')[a] were carried out in German-occupied Poland by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), with the support of parts of the local Ukrainian population, against the Polish minority in Volhynia, Eastern Galicia, parts of Polesia, and the Lublin region from 1943 to 1945.[6]

The peak of the massacres took place in July and August 1943. These killings were exceptionally brutal, and most of the victims were women and children.[7][3] The UPA's actions resulted in up to 100,000 Polish deaths.[8][9][10] Estimates of the death toll range from 60,000[11] to 120,000.[2] Other victims of the massacres included several hundred Armenians, Jews, Russians, Czechs, Georgians, and Ukrainians who were part of Polish families or opposed the UPA and impeded the massacres by hiding Polish escapees.[3]

The ethnic cleansing was a Ukrainian attempt to prevent the post-war Polish state from asserting its sovereignty over Ukrainian-majority areas that had been part of the pre-war Polish state.[12][13][3] The decision to force the Polish population to leave areas that the Banderite faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN-B) considered to be Ukrainian took place at a meeting of military referents[definition needed] in the autumn of 1942, and plans were made to liquidate Polish-community leaders and any of the Polish community who resisted.[14] Local UPA commanders in Volhynia began attacking the Polish population, committing massacres in numerous villages.[15]

Encountering resistance, the UPA commander in Volhynia, Dmytro Klyachkivsky ("Klym Savur"), issued an order in June 1943 for the "general physical liquidation of the entire Polish population".[16] The largest wave of attacks took place in July and August 1943, the assaults in Volhynia continuing until the spring of 1944, when the Red Army arrived in Volhynia and the Polish underground, which had organized Polish self-defense, formed the 27th AK Infantry Division.[17] Approximately 50,000–60,000 Poles died as a result of the massacres in Volhynia, while up to 2,000–3,000 Ukrainians died as a result of Polish retaliatory actions.[18][19][20]

At the 3rd OUN Congress in August 1943, Mykola Lebed criticized the Ukrainian Insurgent Army's actions in Volhynia as "banditry". The majority of delegates disagreed with his assessment, and the congress decided to extend the anti-Polish operation into eastern Galicia.[21] However, it took a different course: by the end of 1943, it was limited to killing leaders of the Polish community and exhorting Poles to flee to the west under threat of looming genocide.[22]

In March 1944, the UPA command, headed by Roman Shuchevych, issued an order to drive Poles out of Eastern Galicia, first with warnings and then by raiding villages, murdering men, and burning buildings.[23] A similar order was issued by the UPA commander in Eastern Galicia, Vasyl Sydor ("Shelest").[24] This order was often disobeyed and entire villages were slaughtered.[25] In Eastern Galicia between 1943 and 1946, OUN-B and UPA killed 20,000–25,000 Poles.[26] 1,000–2,000 Ukrainians were killed by the Polish underground.[27]

Some Ukrainian religious authorities, institutions, and leaders protested [when?] the slayings of Polish civilians, but to little effect.[28]

In 2008 Poland's Parliament adopted a resolution calling UPA's crimes against Poles "crimes bearing the hallmarks of genocide". In 2013 it adopted a resolution calling them "ethnic cleansing with the hallmarks of genocide". On 22 July 2016, Poland's Sejm established 11 July as a National Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Genocide committed by Ukrainian nationalists against citizens of the Second Polish Republic.[29] This characterization is disputed by Ukraine and by some non-Polish historians, who characterize it instead as ethnic cleansing.[30]

Background

Interwar period in Second Polish Republic

The recreated Polish state covered large territories inhabited by Ukrainians, while the Ukrainian movement failed to achieve independence. According to the Polish census of 1931, in Eastern Galicia, the Ukrainian language was spoken by 52% of the inhabitants, Polish by 40% and Yiddish by 7%. In Wołyn (Volhynia), Ukrainian was spoken by 68% of the inhabitants, Polish by 17%, Yiddish by 10%, German by 2%, Czech by 2% and Russian by 1%.[31][32]

Ukrainian radical nationalism

In 1920, exiled Ukrainian officers, mostly former Sich Riflemen and veterans of Polish–Ukrainian War, founded the Ukrainian Military Organization (UVO), an underground military organization with the goal of continuing the armed struggle for independent Ukraine.[33] As soon as the second half of 1922, UVO organized a wave of sabotage actions and assassination attempts on Polish officials and moderate Ukrainian activists.[34] In 1929, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) was formed in Vienna, Austria, and was the result of a union between several radical nationalist and extreme right-wing organisations with UVO.[35] Members of the organization carried out several acts of terror and assassinations in Poland, but it was still rather fringe movement, condemned for its violence by figures from mainstream Ukrainian society such as the head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, Andriy Sheptytsky.[36] The most popular political party among Ukrainians was in fact the Ukrainian National Democratic Alliance (UNDO), which was opposed to Polish rule but called for peaceful and democratic means to achieve independence from Poland.

By the beginning of the Second World War, the membership of OUN had risen to 20,000 active members, and the number of supporters was many times as many.[37]

Polish policy towards Ukrainian minority

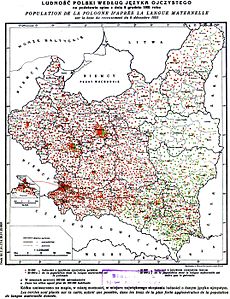

| Polish census of 1931 | |

|---|---|

| Original map showing the distribution of native languages spoken in Poland during the 1931 census. | |

|

The policy of the Polish authorities towards the Ukrainian minority was changeable throughout the interwar period, varying between attempts at assimilation, conciliation and a policy of repression.

For example in 1930 terror campaign and civil unrest in the Galician countryside resulted in Polish police exacting a policy of collective responsibility on local Ukrainians in an effort to "pacify" the region.[38] Ukrainian parliamentarians were placed under house arrest to prevent them from participating in elections, with their constituents terrorized into voting for Polish candidates.[38] Beginning in 1937, the Polish government in Volhynia initiated an active campaign to use religion as a tool for Polonization and to convert the Orthodox population to Roman Catholicism.[39] Over 190 Orthodox churches were destroyed and 150 converted to Roman Catholic churches.[40]

On the other hand just before the war, Volhynia was "the site of one of eastern Europe's most ambitious policies of toleration".[41] Through supporting Ukrainian culture and religious autonomy and the Ukrainization of the Orthodox Church, the Sanacja regime wanted to achieve Ukrainian loyalty to the Polish state and to minimise Soviet influences in the borderline region. That approach was gradually abandoned after Józef Piłsudski's death in 1935.[41][42] Practically all government and administrative positions, including the police, were assigned to Poles.[43]

Harsh policies implemented by the Second Polish Republic were often a response to OUN-B violence,[44] but contributed to a further deterioration of relations between the two ethnic groups. Between 1921 and 1938, Polish colonists and war veterans were encouraged to settle in the Volhynian and Galician countryside; their number reached 17,700 in Volhynia in 3,500 new settlements by 1939.[45] Between 1934 and 1938, a series of violent and sometimes-deadly[46] attacks against Ukrainians were carried out in other parts of Poland.[47] Volhynia was a place of increasingly violent conflict, with Polish police on one side and Western Ukrainian communists supported by many dissatisfied Ukrainian peasants on the other.[citation needed] The communists organized strikes, killed at least 31 suspected police informers in 1935–1936, and assassinated local Ukrainian officials for "collaboration" with the Polish government. The police conducted mass arrests, reported the killing of 18 communists in 1935, and killed at least 31 people in gunfights and during arrest attempts in 1936.[48]

Second World War

Soviet occupation of Volhynia and Eastern Galicia

In September 1939, Poland was invaded by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. The eastern part of Poland was annexed by the Soviet Union; Volhynia and Eastern Galicia were attached to the Ukrainian SSR. After the annexation, the Soviet NKVD started eliminating the predominantly Polish middle and upper classes, including social activists and military leaders. Between 1939 and 1941, 200,000 Poles were deported to Siberia.[49] The deportations and murders deprived the Poles of their community leaders.

During the wartime Soviet occupation, Polish members of the local administration were replaced by Ukrainians and Jews,[50] and the Soviet NKVD subverted the Ukrainian independence movement. All local Ukrainian political parties were abolished. Between 20,000 and 30,000 Ukrainian activists fled to German-occupied territory; most of those who did not escape were arrested. For example, Dmytro Levytsky, head of the UNDO, was arrested along with many of his colleagues, and never heard from again.[51] The elimination by the Soviets of the moderate or liberal political leaders within Ukrainian society allowed the extremist underground OUN to remain the only surviving group with a significant organizational presence among western Ukrainians.[52]

OUN activities 1939–1941

In Kraków on 10 February 1940, a revolutionary faction of the OUN emerged, called the OUN-R or, after its leader Stepan Bandera, the OUN-B (Banderites). This was opposed by the current leadership of the organization, so it split, and the old group was called OUN-M after the leader Andriy Melnyk (Melnykites).[53]

On 22 June 1941, the Soviet Union was attacked by Germany; the Soviets quickly withdrew eastward and left Volhynia. The OUN supported Germans, seized about 213 villages and organized diversion in the rear of the Red Army.[54] The OUN-B formed Ukrainian militias that, displaying exceptional cruelty, carried out antisemitic pogroms and massacres of Jews. The biggest pogroms carried out by the Ukrainian nationalists took place in Lviv, resulting in the massacre of 6,000 Polish Jews.[55][56] The involvement of OUN-B is unclear, but at the very least OUN-B propaganda fuelled antisemitism.[57] The vast majority of pogroms carried out by the Banderites occurred in Eastern Galicia and Volhynia.[58][59] Several hundred Poles were also killed at the hands of Ukrainian nationalists at the time, and a group of about a hundred Polish students were murdered in Lviv.[60]

On 30 June 1941, the OUN-B proclaimed the establishment of Ukrainian State in Lviv. In response to the declaration, OUN-B leaders and associates were arrested and imprisoned by the Gestapo (ca. 1500 persons).[61] The OUN-M continued to operate openly, collaborating with the Germans and taking over local administration, but its leaders also began to be arrested and the organisation's influence was curtailed by the Germans in early 1942.[62] Meanwhile, the OUN-B, unwilling and unable to openly resist the Germans, began methodically creating a clandestine organization, engaging in propaganda work, and building weapons stockpiles.[63] It set out to infiltrate the local collaborationist police, from which it received training and weapons. The auxiliary police assisted the German SS in the murder by shooting of approximately 200,000 Volhynian Jews, and their experience both led them to believe the Germans would turn on them next and taught them how to make use of genocidal techniques.[64]

In the Chełm region, 394 Ukrainian community leaders were killed by the Poles on the grounds of collaboration with German authorities.[65]

Polish underground in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia

During the Soviet occupation, the Polish underground in the eastern territories collapsed. However, after the Germans took control of the area, the structures of the Home Army (AK) were rebuilt. In Volhynia, an Independent District of the Home Army was established, while in Eastern Galicia the Lwów Area of the Home Army was created. The former numbered around 8,000 sworn soldiers at the end of 1943, while the latter numbered around 27,000 at the beginning of 1944.[66] The Polish forces were preparing to launch an anti-German uprising once the German army disintegrated. From 1943 onwards, the plan was to focus on capturing Lwów and western Volhynia once the Red Army arrived, and a fight against Ukrainian forces was also anticipated.[67]

Due to OUN's collaboration with the Nazis, local Poles generally thought there is no possibility for reconciliation and that Ukrainians ought to be deported to Soviet Ukraine after the war. Such view was shared by the local Home Army command, but the Polish authorities in Warsaw and London took a more moderate stance, discussing the possibility of limited Ukrainian autonomy.[68][69]

Polish-Ukrainian antagonism

Both the Polish government-in-exile and the underground state and the Ukrainian OUN-B considered the possibility that in the event of mutually exhaustive attrition warfare between Germany and the Soviet Union, the region would become a scene of conflict between Poles and Ukrainians. In early 1943, the Polish underground considered the possibility of rapprochement with Ukrainians, which proved fruitless since neither side was willing to sacrifice their claims.[70]

The field of competition was the occupation administration. As a rule, the Germans preferred Ukrainians and filled administrative positions with them. However, a shortage of suitably qualified people forced the Germans to reach out to Poles, who began to gain the upper hand in lower-level administration during 1942.[71] This process caused unrest in the Ukrainian underground.[72]

Even in the interwar period, the OUN adhered to concepts of integral nationalism in its totalitarian form, which stipulated that a Ukrainian state must be ethnically homogeneous and the only way to defeat the Polish enemy was through the elimination of Poles from Ukrainian territories. From the OUN-B perspective, the Jews had already been annihilated, and the Russians and Germans were only temporarily in Ukraine, but Poles had to be forcefully removed.[73] The OUN-B came to believe that it had to move fast while the Germans still controlled the area in order to pre-empt future Polish efforts to re-establish Poland's prewar borders. The result was that the local OUN-B commanders in Volhynia and Galicia, if not the OUN-B leadership itself, decided that ethnic cleansing of Poles from the area through terror and murder to be necessary.[73]

Only one faction of Ukrainian nationalists, OUN-B under Mykola Lebed and then Roman Shukhevych, was committed to the ethnic cleansing of Volhynia. Taras Bulba-Borovets, the founder of the Ukrainian People's Revolutionary Army, rejected the idea and condemned the anti-Polish massacres when they started.[74][75] The OUN-M leadership did not believe that such an operation was advantageous in 1943.[73]

Massacres

Volhynia

Creation of UPA

By late 1942, the OUN-B in Volhynia was avoiding conflict with the German authorities and working with them; anti-German resistance was limited to Soviet partisans on the extreme northern edge of Volhynia, small bands of OUN-M fighters, and to a group of guerillas knowns as the UPA or the Polessian Sich, unaffiliated with the OUN-B and led by Taras Bulba-Borovets of the exiled Ukrainian People's Republic.[63] Soviet partisans raided local settlements in search of supplies. Soon Germans began "pacifying" entire villages in Volhynia in retaliation for real or alleged support of Soviet partisans; the raids were often conducted by Ukrainian auxiliary police units under the direct supervision of Germans.[76] One of the best-known examples was the pacification of Obórki, a village in Lutsk County, on 13–14 November 1942.[77][78]

In October 1942, OUN-B decided to form its own partisans, called OUN Military Detachments. Individual units entered active combat in February 1943 (first came the sotnia of Hryhoriy Perehinyak attack on German police station in Volodymyrets on 7 February).[79] At the third OUN-B conference (17–23 February 1943), the decision was made to launch an anti-German uprising in order to liberate as much territory as possible before the arrival of the Red Army. The uprising was to break out first in Volhynia; therefore, the formation of a partisan army called the Ukrainian Liberation Army began there.[80] The uprising broke out in mid-March, with Dmytro Klyachkivsky and Vasyl Ivakhiv leading it, then Klyachkivsky alone after Ivakhiv's death in May that year. It was also at that time that the name Ukrainian Liberation Army was abandoned and the name Ukrainian Insurgent Army, hijacked from Bulba-Borovets, began to be used, thus impersonating it. The base of the new army was made up of Ukrainian policemen, approximately 5,000 of whom deserted en masse between March and April 1943, and men absorbed from Bulba-Borovets and OUN-M units. By July 1943, the UPA had twenty thousand soldiers.[81] According to Timothy Snyder, in their struggle for dominance, OUN-B forces would kill tens of thousands of Ukrainians for supposed links to Melnyk or Bulba-Borovets.[74]

Even before the anti-German uprising began, OUN-B units started attacking Polish villages and murdering Poles. The attacks soon turned into a full-scale extermination campaign, aimed at killing off or driving out the Polish population from areas considered by OUN-B to be Ukrainian. With dominance secured in spring 1943, when the UPA had gained control over the Volhynian countryside from the Germans, the UPA began large-scale operations against the Polish population.[49][73]

First massacres

Between 1939 and 1943, the share of Polish population in Volhynia had dropped to about 8% (approximately 200,000 inhabitants). Volhynian Poles were dispersed across rural areas, Soviet deportations stripped them of their community leaders, and they had neither own local partisan army nor state power (with exception of the German occupants) to turn to for protection.[82]

On 9 February 1943, a UPA group, commanded by Hryhory Perehyniak, pretended to be Soviet partisans and assaulted the Parośle settlement in Sarny county.[83] It is considered a prelude to the massacres and is recognized as the first mass murder committed by the UPA in the area.[84] Estimates of the number of victims range from 149[85] to 173.[86]

Throughout Volhynia, individuals, often with their families, began to be killed, while in the Kostopol and Sarny counties in the northeastern part of Volhynia, where Ivan Lytvynchuk "Dubovy" was in command, the UPA proceeded to systematically murder Poles.[87] They attacked dozens of villages, the largest massacre of which took place in Lipniki, where one of the first Polish self-defences was established, but despite resistance during the attack on the night of 26–27 March, the "Dubovy" unit murdered 184 people.[87] About 130 people were murdered in Brzezina on 8 April 1943.[88] Then the massacres began to be carried out in the westward located counties, mainly in the Lutsk county.[89] According to Timothy Snyder, in late March and early April 1943, the UPA forces killed 7,000 Polish civilians.[90]

Wave of massacres during Holy Week of 1943

The OUN-B and UPA leadership chose Holy Week (18–26 April) as the period for an organised attack on the Polish population, which was to include the western counties of Równo and Krzemieniec, where Petro Oilynyk "Eney" was in command.[91]

Several villages was attacked, but the most bloody was the massacre of the night of 22–23 April in Janowa Dolina, where UPA unit commanded by Ivan Lytvynchuk "Dubovy" killed 600 people and burned down the entire village.[92] In another massacre, according to the UPA reports, the Polish colonies of Kuty, in the Szumski region, and Nowa Nowica, in the Webski region, were liquidated for co-operation with the Gestapo and the other German authorities.[93] According to Polish sources, the Kuty self-defense unit managed to repel a UPA assault, but at least 53 Poles were murdered. The rest of the inhabitants decided to abandon the village and were escorted by the Germans who arrived at Kuty, alerted by the glow of fire and the sound of gunfire.[94]

The assaults spread throughout the eastern Volhynia, and in some localities Poles managed to organise self-defence units that were able to repel attacks by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, but in most cases the UPA slaughtered and burned Polish villages. In May and June, the purge extended to Petro Olijnyk's subordinate areas of the Rivne and Kremenets districts.[94] Maksym Skorupskyi, one of the UPA commanders, wrote in his diary: "Starting from our action on Kuty, day by day after sunset, the sky was bathing in the glow of conflagration. Polish villages were burning".[94]

Polish proposals for a truce

The local Home Army command, under Col. Kazimierz Bąbiński "Luboń", responded to the attacks by organising local self-defences, of which about 100 were formed by July 1943, in a bid to protect the population and prevent them from fleeing to the cities. It was determined to fight the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), not believing there was any possibility of an agreement, but at the same time it was obliged to carry out the plan of an anti-German general uprising, which ordered it to spare its forces until the Soviet-German front arrived.[95] On the opposite side was the local Government Delegate, Kazimierz Banach "Jan Linowski", who still believed in the plan agreed with headquarters and Home Army commander General Rowecki to reach an agreement with the Ukrainians, which he had been trying to implement since 1942.[96]

Among local Home Army soldiers, Banach had a reputation as a traitor. Banach attempted to hold talks with the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) through the local OUN SB commander Shabatura. Preliminary talks took place on 7 July. For the second round on 10 July, the plenipotentiary of the District Delegation, Zygmunt Rumel "Krzysztof Poręba", and the representative of the Volhynia District of the AK Krzysztof Markiewicz "Czart", together with the coachman Witold Dobrowolski, went. All three were brutally murdered on 10 July 1943 in the village of Kustycze.[97] This event ultimately discredited the stance taken by Banach. A plan was drawn up in the Home Army command to organise a military operation against the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) to thwart the next wave of genocidal attacks, which, according to intelligence information, was planned for 20 July.[98]

July wave of massacres

The Soviet victories acted as a stimulus for the escalation of massacres in July 1943, when the ethnic cleansing reached its peak.[50] In the 1990s, a citation from an alleged "secret directive" by Dmytro Klyachkivsky (head-commander of the UPA-North) was published by Polish historian Władysław Filar:

We should make a large action of the liquidation of the Polish element. As the German armies withdraw, we should take advantage of this convenient moment for liquidating the entire male population in the age from 16 up to 60 years. We cannot lose this fight, and it is necessary at all costs to weaken Polish forces. Villages and settlements lying next to the massive forests, should disappear from the face of the earth.[99][100]

Full text of the "secret order" was never published and its authenticity is questioned.[101]

The UPA command decided to extend the genocidal action to the western areas of Volhynia, the districts of Horochów, Kowel and Vladimir, an area more densely populated by Poles. The action was to be coordinated to exploit the element of surprise to the maximum. The day after murder of Polish emissaries, 11 July 1943, was the start of the operation and is regarded as the bloodiest day of the massacres,[102] with many reports of UPA units marching from village to village and killing Polish civilians.[103] On that day, UPA units surrounded and attacked Polish 96 villages and settlements located in counties Horochów, and Włodzimierz Wołyński, and 3 in Kowel county. Fifty villages in the first two counties were attacked the following day.[104]

In the Polish village of Gurów, out of 480 inhabitants, only 70 survived; in the settlement of Orzeszyn, the UPA killed 306 out of 340 Poles; in the village of Sadowa out of 600 Polish inhabitants, only 20 survived.[103] In Zagaje 260 Poles was killed.[105] The wave of massacres lasted five days until July 16. The UPA continued the ethnic cleansing, particularly in rural areas, until most Poles had been deported, killed or expelled. The thoroughly-planned actions were conducted by many units and were well-coordinated.[50] In August 1943, the Polish village of Gaj, near Kovel, was burned and some 600 people were massacred, and 438 people were killed, including 246 children, in Ostrówki. In July 1943, a total of 520 Polish villages were attacked, killing 10,000–11,000 Poles. At the same time, the killings in the eastern part of the county continued.[104]

August wave of massacres

Another large wave of slaughter of the Polish population took place on 29 and 30 August 1943, this time also covering the Luboml district.[106] The killings continued until mid-September.[107]

During the night of August 30 Ivan Klimchak "Lysiy" unit surrounded the village of Kąty, where Poles were murdered farm by farm, killing 180–213 people.[108] Then, on August 31, the unit killed 86–87 people in the village of Jankowce.[108] On the same day they surrounded the village of Ostrówek. The population was gathered in the school and church, valuables were taken away. Then the men were killed with blunt tools in three different places. The rest of the population was shot in the cemetery. A total of 476 to 520 people were killed.[108] Another unit entered the village of Wola Ostrowiecka on the morning of 30 August. Children were treated with candy, and a speech was made to the population calling for a joint fight against the Germans, then the entire population was gathered in the school. Men were led outside and killed with axes and blunt tools, then the school, with women and children inside, was set on fire and pelted with grenades.[108] Overall 572–520 people were killed.[108] In total, several hundred Polish villages were attacked in August 1943.

In the eastern part of Volhynia the slaughter of the Polish population continued, the attacks were generally not coordinated, the UPA units attacking those Polish villages that still survived. Many of them had been turned into self-defence points, so the massacres were often preceded by fights, sometimes the defenders managed to repel the UPA units.[109]

In the summer of 1943, in Volhynia, every Pole and every person with Polish roots was facing death at the hands of Ukrainian nationalists. Ukrainians with Polish roots were also killed, as were people from mixed families. Poles could only feel relatively safe in self-defence bases and larger towns.[110] One Polish refugee from Volhynia wrote at the time: "All around dead bodies and potential victims. It smells of corpses from every Pole now. There are living corpses walking around."[111]

Polish self-defence and reprisal

After unsuccessful attempts to conclude a truce with the UPA, the Polish underground moved to active defence and offensive actions. On 20 July 1943, decisions were made to form nine partisan units, totalling around a thousand men.[112] Their task was to support Polish self-defences and to attack UPA bases. There was a growing desire among the Polish population to retaliate against the Ukrainians. It is estimated that around 2,000 people were killed in Polish attacks on Ukrainian villages.[113]

The last wave of massacres in Volhynia in the winter of 1943–1944

The UPA's command decided to take advantage of the coming Soviet offensive to launch a final liquidation action against the Polish population.[114] It was decided to attack those villages from which German or Hungarian units had already withdrawn and the Soviets had not yet entered.[114] Many partisan units also undertook offensive actions against the Germans, making it impossible for them to protect the civilian population.[115] The attacks began on 7 December with assaults on the villages of Budki Borowskie, Dołhań and Okopy.[116] Most assaults took place right before Christmas. The attacks continued until March. One of the bloodiest massacres took place in Wiśniowiec, in February 1944, when the OUN SB units managed to capture the Monastery of the Discalced Carmelites, which had been attacked several times during 1943.[116] Almost all of the 300–400 Poles hiding there, including monks, were killed, as well as 138 people in neighbouring Wiśniowiec Stary.[117]

Operations of the 27th Volhynian Infantry Division of the Home Army

In January 1944, at the same time as the UPA was carrying out its last wave of massacres of the Polish population, the units of the Home Army in Volhynia embarked on the implementation of Operation Tempest, i.e. an anti-German uprising. To this end, AK units from across Volhynia were to assemble in western Volhynia to form the 27th Volhynian Infantry Division. However, some units, mainly those forming part of self-defences, refused to carry out the order, not wanting to leave the civilian population at the mercy of the UPA.[118] Despite this, the division was formed and managed to capture a part of Volhynia between Kovel and Volodymyr-Volynskyi. Fearful of being surrounded by UPA units, the division began fighting them. From 11 January to 18 March 1944, the division fought sixteen major clashes with the Ukrainians, coming out mostly successful.[119] The Ukrainian population was expelled from the captured villages in the area of Svynaryn forest and its surroundings. Ukrainian sources state that the division's soldiers committed atrocities in some Ukrainian villages, the greatest of which would be the crime in Ochniwka, where, according to Yaroslav Tsaruk (Ukrainian: Ярослав Царук), 166 people were allegedly killed.[120]

After the battles with the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, the division fought almost exclusively against the Germans, soon withdrawing from Volhynia to the Lublin region.

Reactions of other Ukrainian organisations

The killings were opposed by the Ukrainian Central Committee under Volodymyr Kubiyovych. In response, UPA units murdered Ukrainian Central Committee representatives and a Ukrainian Catholic priest who had read an appeal by the Ukrainian Central Committee from his pulpit.[121]

Eastern Galicia

Polish-Ukrainian tension in Eastern Galicia

The Polish underground stood firm on the integrity of the pre-war borders, but was prepared to make certain concessions to the Ukrainians. At the same time, it was convinced that the OUN, faced with a choice between western Ukraine belonging to the USSR or Poland, would ultimately opt for Poland.[122] However, the OUN rejected these proposals, issuing statements accusing the Polish population of collaboration with the Germans and Soviets. In this atmosphere, and against the backdrop of the ongoing ethnic cleansing of the Polish population in Volhynia, talks between the Polish underground and the OUN Central Provision had been taking place since the summer of 1943 on a possible agreement.[123] The last meeting took place on 8 March 1944.[124]

Decision to carry out anti-Polish action in Eastern Galicia

At the 3rd OUN Congress in August 1943, Mykola Lebed and Mykhailo Stepaniak criticised the UPA's actions in Volhynia as "bandit".[124] The majority of delegates, however, opposed his assessment and opted for transferring the Volhynian actions against Poles into Galicia.[125] It is not clear when the final decision was made, it was probably made by Shuchevych, at that time already the commander of the OUN-B and UPA, after inspecting Volhynia and seeing the effects of the action in the region.[125]

Ethnic cleansing

In late 1943 and early 1944, after most Poles in Volhynia had either been murdered or had fled the area, the conflict spread to the neighboring province of Galicia, where most of the population was still Ukrainian, but the Polish presence was strong. Unlike in the case of Volhynia, where Polish villages were usually destroyed and their inhabitants murdered without warning, in eastern Galicia, Poles were sometimes given the choice of fleeing or being killed. An order by a UPA commander in Galicia stated, "Once more I remind you: first call upon Poles to abandon their land and only later liquidate them, not the other way around". The choice of other tactics, combined with better Polish self-defence and a demographic balance more favorable to Poles, resulted in a significantly lower death toll among Poles in Galicia than in Volhynia.[126]

The methods used by Ukrainian nationalists in this area were the same: rounding up and killing all the Polish residents of the villages and then looting the villages and burning them to the ground.[50] On 28 February 1944, in the village of Korosciatyn 135 Poles were murdered;[127] the victims were later counted by a local Roman Catholic priest, Mieczysław Kamiński.[128] Jan Zaleski (father of Tadeusz Isakowicz-Zaleski) who witnessed the massacre, wrote in his diary: "The slaughter lasted almost all night. We heard terrible cries, the roar of cattle burning alive, shooting. It seemed that Antichrist himself began his activity!"[129] Kamiński claimed that in Koropiec, where no Poles were actually murdered, a local Greek Catholic priest, in reference to mixed Polish-Ukrainian families, proclaimed from the pulpit: "Mother, you're suckling an enemy – strangle it."[130] Among the scores of Polish villages whose inhabitants were murdered and all buildings burned are places like Berezowica, near Zbaraz; Ihrowica, near Ternopil; Plotych, near Ternopil; Podkamien, near Brody; and Hanachiv and Hanachivka, near Przemyślany.[131]

Roman Shukhevych, a UPA commander, stated in his order from 25 February 1944: "In view of the success of the Soviet forces it is necessary to speed up the liquidation of the Poles, they must be totally wiped out, their villages burned... only the Polish population must be destroyed".[32]

One of the most infamous massacres took place on 28 February 1944 in the Polish village of Huta Pieniacka, with over 1,000 inhabitants. The village had served as a shelter for refugees including Polish Jews[132] as well as a recuperation base for Polish and communist partisans. One AK unit was active there. In the winter of 1944, a Soviet partisan unit numbering 1,000 was stationed in the village for two weeks.[132][133][134] Huta Pieniacka's villagers, although poor, organized a well-fortified and armed self-defense unit, which fought off a Ukrainian and German reconnaissance attack on 23 February 1944.[135][unreliable source?] Two soldiers of the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Galicia (1st Ukrainian) Division of the Waffen-SS were killed and one wounded by the villagers. On February 28, elements of the Ukrainian 14th SS Division from Brody returned with 500–600 men, assisted by a group of civilian nationalists. The killing spree lasted all day. Kazimierz Wojciechowski, the commander of the Polish self-defense unit, was drenched with gasoline and burned alive at the main square. The village was utterly destroyed and all of its occupants killed.[133] The civilians, mostly women and children, were rounded up at a church, divided and locked into barns, which were set on fire.[136] Estimates of casualties in the Huta Pieniacka massacre vary and include 500 (Ukrainian archives),[137] over 1,000 (Tadeusz Piotrowski),[138] and 1,200 (Sol Littman).[139] According to IPN investigation, the crime was committed by the 4th battalion of the Ukrainian 14th SS Division[136] supported by UPA units and local Ukrainian civilians.[140]

A military journal of the Ukrainian 14th SS Division condemned the killing of Poles. In a 2 March 1944 article addressed to the Ukrainian youth, which was written by military leaders, Soviet partisans were blamed for the murders of Poles and Ukrainians, and the authors stated, "If God forbid, among those who committed such inhuman acts, a Ukrainian hand was found, it will be forever excluded from the Ukrainian national community".[141] Some historians deny the role of the Ukrainian 14th SS Division in the killings and attribute them entirely to German units, but others disagree.[142][verification needed] According to Yale historian Timothy Snyder, the Ukrainian 14th SS Division's role in the ethnic cleansing of Poles from western Ukraine was marginal.[143]

The village of Pidkamin (Podkamień), near Brody, was a shelter for Poles, who hid in the monastery of the Dominicans there. Some 2,000 persons, mostly women and children, were living there when the monastery was attacked in mid-March 1944 by the UPA units, which Polish Home Army accounts accused of co-operating with the Ukrainian SS. Over 250 Poles were killed.[132] In the nearby village of Palikrovy, 300 Poles were killed, 20 in Maliniska and 16 in Chernytsia. Armed Ukrainian groups destroyed the monastery and stole all valuables. What remained was the painting of Mary of Pidkamin, which now is kept in St. Wojciech Church in Wrocław. According to Kirichuk, the first attacks on the Poles took place there in August 1943 and were probably the work of the UPA units from Volhynia. In retaliation, Poles killed important Ukrainians, including a Ukrainian doctor from Lviv, called Lastowiecky and a popular football player from Przemyśl, called Wowczyszyn.

By the end of the summer, mass acts of terror aimed at Poles were taking place in Eastern Galicia to force Poles to settle on the western bank of the San River under the slogan "Poles behind the San". Snyder estimates that 25,000 Poles were killed in Galicia alone,[144] and Grzegorz Motyka estimated the number of victims at 30,000–40,000.[10]

The slaughter did not stop after the Red Army entered the areas, with massacres taking place in 1945 in such places as Czerwonogrod (Ukrainian: Irkiv), where 60 Poles were murdered on February 2, 1945,[145][146] the day before they were scheduled to depart for the Recovered Territories.

By Autumn 1944, anti-Polish actions stopped, and terror was used only against those who co-operated with the NKVD, but in late 1944-early 1945, the UPA performed a last massive anti-Polish action in the Ternopil region.[147] On the night of 5–6 February 1945, Ukrainian groups attacked the Polish village of Barysz, near Buchach; 126 Poles were massacred, including women and children. A few days later, on 12–13 February, a local group of OUN under Petro Khamchuk attacked the Polish settlement of Puźniki, killed around 100 people and burned houses. Most of those who survived moved to Niemysłowice near Prudnik, Silesia.[148]

Approximately 150[149]–366 Ukrainian and a few Polish inhabitants of Pawłokoma were killed on 3 March 1945 by a former Polish Home Army unit, aided by Polish self-defense groups from nearby villages. The massacre is believed to be an act of retaliation for earlier alleged murders by UPA of 9 or 11 Poles[150] in Pawłokoma and unspecified number of Poles killed by the UPA in the neighboring villages.

Atrocities

Attacks on Poles during the massacres in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia were marked with extreme sadism and brutality. Rape, torture and mutilation were commonplace, with entire villages wiped out as a result. Poles were burned alive, flayed, impaled, crucified, disembowelled, dismembered and beheaded. Women were gang raped and had their breasts sliced off, children were hacked to pieces with axes, babies were impaled on bayonets and pitchforks or bashed against trees.[151][152]

According to a document by the Polish underground, the crimes were atrocious:[152]

In all villages, settlements and colonies, without exception, the Ukrainians carried out the operation of murdering Poles with monstrous cruelty. Women – even pregnant ones – were nailed to the ground with bayonets, children were ripped apart by their legs, others were impaled on pitchforks and thrown over fences, members of intelligentsia were tied with barbed wire and thrown into wells, arms, legs and heads were chopped off with axes, tongues were cut out, ears and noses were cut off, eyes were gouged, genitals were butchered, bellies ripped open and entrails pulled out, heads were smashed with hammers, living children were thrown inside burning houses. The barbaric frenzy reached a point that people were sawed apart alive, women had their breasts severed; others were impaled or beaten to death with sticks. Many people were killed – after a death sentence – by having their hands and feet chopped off, and only then their heads.

According to eyewitness Tadeusz Piotrowski about the fate of his friend's family:[151]

First, they raped his wife. Then, they proceeded to execute her by tying her up to a nearby tree and cutting off her breasts. As she hung there bleeding to death, they began to hurl her two-year-old son against the house wall repeatedly until his spirit left his body. Finally, they shot her two daughters. When their bloody deeds were done and all had perished, they threw the bodies into a deep well in front of the house. Then, they set the house ablaze.

The atrocities were carried out indiscriminately and without restraint. The victims, regardless of their age or gender, were routinely tortured to death. Norman Davies in No Simple Victory gives a short but shocking description of the massacres:

Villages were torched. Roman Catholic priests were axed or crucified. Churches were burned with all their parishioners. Isolated farms were attacked by gangs carrying pitchforks and kitchen knives. Throats were cut. Pregnant women were bayoneted. Children were cut in two. Men were ambushed in the field and led away. The perpetrators could not determine the province's future. But at least they could determine that it would be a future without Poles.[153]

An OUN order from early 1944 stated:

Liquidate all Polish traces. Destroy all walls in the Catholic Church and other Polish prayer houses. Destroy orchards and trees in the courtyards so that there will be no trace that someone lived there.... Pay attention to the fact that when something remains that is Polish, then the Poles will have pretensions to our land".[154]

UPA commander's order of 6 April 1944 stated: "Fight them [the Poles] unmercifully. No one is to be spared, even in case of mixed marriages".[155]

Timothy Snyder describes the murders: "Ukrainian partisans burned homes, shot or forced back inside those who tried to flee, and used sickles and pitchforks to kill those they captured outside. In some cases, beheaded, crucified, dismembered, or disemboweled bodies were displayed, in order to encourage remaining Poles to flee".[49] The Ukrainian historian Yuryi Kirichuk described the conflict as similar to medieval peasant uprisings.[156]

According to the Polish historian Piotr Łossowski, the method used in most of the attacks was the same. At first, local Poles were assured that nothing would happen to them. Then, at dawn, a village was surrounded by armed members of the UPA, behind whom were peasants with axes, knives, hatchets, hammers, pitchforks, shovels, sickles, scythes, hoes and various other farming tools. All of the Poles who were encountered were murdered; most were killed in their homes but sometimes they were herded into churches or barns which were then set on fire. Many Poles were thrown down wells or killed and then buried in shallow mass graves as well. After a massacre, all goods were looted, including clothes, grain and furniture. The final part of an attack was setting fire to the entire village.[157] All vestiges of Polish existence were eradicated, even abandoned Polish settlements were burned to the ground.[50]

Even though it may be an exaggeration to say that the massacres enjoyed the general support of the Ukrainians, it has been suggested that without wide support from local Ukrainians, they would have been impossible.[49] The Ukrainian peasants who took part in the killings created their own groups, the SKV or Samoboronni Kushtchovi Viddily (Самооборонні Кущові Відділи, СКВ). Many of their victims who were perceived as Poles, even despite not knowing the Polish language, were murdered by СКВ along with the others.[158]

The violence reached its peak on 11 July 1943 known to many Poles as "Bloody Sunday" when the UPA carried out attacks on 100 Polish villages in Volhynia burning them to the ground and slaughtering some 8,000 Polish men, women and children including patients and nurses at a hospital. These attacks as well as others could have been stopped at anytime by the Germans who in some cases were stationed in garrisons in or near the villages that were attacked. German soldiers however were given orders not to intervene. In some cases individual German soldiers and officers made deals with the UPA to give weapons and other materials to them in exchange for a share of the loot taken from Poles.

Ukrainians in ethnically mixed settlements were offered material incentives to convince them to assist in the attacks on their Polish neighbors or warned by the UPA's security service (Sluzhba Bezbeky) to leave by night, and all remaining inhabitants were murdered at dawn. Many Ukrainians risked and in some cases lost their lives for trying to shelter or warn Poles.[49][159] Such activities were treated by the UPA as collaboration with the enemy and severely punished.[160] In 2007, the Polish Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) published a document, Kresowa Księga Sprawiedliwych 1939–1945. O Ukraińcach ratujących Polaków poddanych eksterminacji przez OUN i UPA ("Borderland's Book of the Righteous. About Ukrainians saving Poles from extermination of OUN and UIA"). The author of the book, IPN's historian Romuald Niedzielko, documented 1341 cases in which Ukrainian civilians helped their Polish neighbours, which caused 384 Ukrainians to be executed by the UPA.[161]

In Polish-Ukrainian families, one common UPA instruction was to kill one's Polish spouse and children born of that marriage. People who refused to carry such an order were often murdered, together with their entire family.[32][162]

According to Ukrainian sources, in October 1943 the Volhynian delegation of the Polish government estimated the number of Polish casualties in Sarny, Kostopol, Równe and Zdołbunów counties to exceed 15,000.[163] Timothy Snyder estimates that in July 1943, the UPA actions resulted in the deaths of at least 40,000 Polish civilians in Volhynia (in March 1944, another 10,000 were killed in Galicia),[164] causing additional 200,000 Poles to flee west before September 1944 and 800,000 afterward.[49][164]

Self-defence organizations

The massacres prompted Poles in April 1943 to begin to organize in self-defence, 100 of such organizations being formed in Volhynia in 1943. Sometimes, self-defence organizations obtained arms from the Germans, but other times, the Germans confiscated their weapons and arrested the leaders. Many of the organizations could not withstand the pressure of the UPA and were destroyed. Only the largest self-defense organizations, which were able to obtain help from the Home Army or Soviet partisans, were able to survive.[165] Kazimierz Bąbiński, commander of the Union for Armed Struggle-Home Army Wołyń in his order to AK partisan units stated:[166]

I forbid the use of the methods utilized by the Ukrainian butchers. We will not burn Ukrainian homesteads nor kill Ukrainian women and children in retaliation. The self-defence network must protect itself from the aggressors or attack the aggressors but leave the peaceful population and their possessions alone.

— "Luboń"

On 20 July 1943, Polish self-defense units were ordered to subordinate themselves to the Home Army's control. Ten days later, the Home Army declared itself in support of an independent Ukrainian state that would encompass non-Polish inhabited areas, and made an appeal to end the civilian bloodshed.[167]

Polish self-defence organizations started to take part in revenge massacres of Ukrainian civilians in the summer of 1943, when Ukrainian villagers who had nothing to do with the massacres suffered at the hands of Polish partisan forces. Evidence includes a letter dated 26 August 1943 to the local Polish self-defence in which the AK commander Kazimierz Bąbiński criticized the burning of neighboring Ukrainian villages, the killing of any Ukrainian who crossed its path and the robbing of Ukrainians of their material possessions.[168] The total number of Ukrainian civilians murdered in Volyn in retaliatory acts by Poles is estimated at 2,000–3,000.[169]

The 27th Home Army Infantry Division was established in January 1944 with the purpose of fighting the UPA and later the German forces.[167]

German involvement

While Germans actively encouraged the conflict, they tried not to get directly involved. Special German units formed from the collaborationist Ukrainian and later the Polish auxiliary police were deployed in pacification actions in Volhynia, and some of their crimes were attributed to the Home Army or to the UPA.[citation needed]

According to Yuriy Kirichuk the Germans actively prodded both sides of the conflict against each other.[170] Erich Koch once said: "We have to do everything possible so that a Pole meeting a Ukrainian, would be willing to kill him and conversely, a Ukrainian would be willing to kill a Pole". Kirichuk quotes a German commissioner from Sarny who responded to the Polish complaints: "You want Sikorski, the Ukrainians want Bandera. Fight each other".[170]

The Germans replaced Ukrainian policemen who deserted from the German service with Polish policemen. Around 1,200 local Poles joined the police, mainly out of desire to avenge UPA atrocities and to obtain means to defend themselves.[171] German policy called for the murder of the family of every Ukrainian police officer who deserted and the destruction of the village of any Ukrainian police officer who deserted with his weapons. Those retaliations were carried out using newly recruited Polish policemen. Polish participation in the German police followed UPA attacks on Polish settlements, but it provided Ukrainian nationalists with useful sources of propaganda and was used as a justification for the ethnic cleansing. The OUN-B leader summarized the situation in August 1943 by saying that the German administration "uses Polaks in its destructive actions. In response we destroy them unmercifully".[93] Despite the desertions in March and April 1943, Ukrainian policemen continued to comprise a significant part of the auxiliary police forces and to pacify Polish and other villages under German orders.[172]

On 25 August 1943, the German authorities ordered all Poles to leave the villages and settlements and to move to larger towns.[citation needed]

Soviet partisan units in the area were aware of the massacres. On 25 May 1943, the commander of the Soviet partisan forces of the Rivne area stressed in his report to the headquarters that Ukrainian nationalists did not shoot the Poles but cut them dead with knives and axes, with no consideration for age or gender.[173]

Number of victims

According to historian George Liber,

the range of these estimates is very broad and must be treated with considerable caution... It is tempting to split the difference between the high and low estimates or to use the highest number of civilian victims to rationalize claims of ethnic cleansing or genocide...[174]

Polish casualties

The death toll among civilians murdered during the Volhynia Massacre is still being researched. At least 10% of ethnic Poles in Volhynia were killed by the UPA, according to Ivan Katchanovski, and thus "Polish casualties comprised about 1% of the prewar population of Poles on territories where the UPA was active and 0.2% of the entire ethnically Polish population in Ukraine and Poland".[175] Łossowski emphasizes that documentation is far from conclusive, as in numerous cases, no survivors were later able to testify.[citation needed]

The Soviet and German invasions of prewar eastern Poland, the UPA massacres, and the postwar Soviet expulsions of Poles contributed to the virtual elimination of a Polish presence in the region. Those who remained left Volhynia, mostly for the neighbouring province of Lublin. After the war, the survivors moved further west to the territories of Lower Silesia. Polish orphans from Volhynia were kept in several orphanages, with the largest of them around Kraków. Several former Polish villages in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia no longer exist, and those that remain are in ruins.[citation needed]

The Institute of National Remembrance estimates that 100,000 Poles were killed by the Ukrainian nationalists (40,000–60,000 victims in Volhynia, 30,000–40,000 in Eastern Galicia and at least 4,000 in Lesser Poland, including up to 2,000 in the Chełm region).[176] For Eastern Galicia, other estimates range between 20,000 and 25,000,[177] 25,000 and 30,000–40,000.[10] In his 2006 general history of WWII, Niall Ferguson gives the total number of Polish victims in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia as between 60,000 and 80,000.[178] G. Rossolinski-Liebe estimated 70,000–100,000.[179] John P. Himka says that "perhaps a hundred thousand" Poles were killed in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia.[8] According to Motyka, from 1943 to 1945 in all territories covered by the conflict, approximately 100,000 Poles were killed.[180] Ivan Katchanovski, a Ukrainian political scientist, writes that, according to Polish and Western estimates, 35,000–60,000 Poles were killed by the UPA in Volhynia alone; he states: "the lower bound of these estimates [35,000] is more reliable than higher estimates which are based on an assumption that the Polish population in the region was several times less likely to perish as a result of Nazi genocidal policies compared to other regions of Poland and compared to the Ukrainian population of Volhynia".[175] Władysław Siemaszko and his daughter Ewa have documented 33,454 Polish victims, 18,208 of whom are known by surname.[181] (in July 2010, Ewa increased the accounts to 38,600 documented victims, 22,113 of whom are known by surname[182]). At the first-ever joint Polish-Ukrainian conference in Podkowa Leśna, organized on June 7–9, 1994 by Karta Centre, and subsequent Polish-Ukrainian historian meetings, with almost 50 Polish and Ukrainian participants, an estimate of 50,000 Polish deaths in Volhynia was settled on,[183] which they considered to be moderate.[citation needed] According to the sociologist Piotrowski, the UPA actions resulted in an estimated number of 68,700 deaths in Wołyń Voivodeship.[184] Per Anders Rudling states that the UPA killed 40,000–70,000 Poles in the area.[32] Some extreme estimates place the number of Polish victims as high as 300,000.[185][verification needed] Also, the numbers include Polonized Armenians killed in the massacres, such as in Kuty.[186] The studies from 2011[clarification needed] quote 91,200 confirmed deaths, 43,987 of which are known by name.[187]

Ukrainian casualties

After the initiation of the massacres, Polish self-defense units responded in kind. All conflicts resulted in Poles taking revenge on Ukrainian civilians.[7] A. Rudling estimates Ukrainian casualties which were caused by Polish retribution at 2,000–3,000 in Volhynia.[32] G. Rossolinski-Liebe puts the number of Ukrainians, both OUN-UPA members and civilians, killed by Poles during and after World War II to be 10,000–20,000.[179] According to Kataryna Wolczuk, for all of the areas affected by conflict, the Ukrainian casualties range from 10,000 to 30,000 between 1943 and 1947.[188] According to Motyka, the author of a fundamental monograph about the UPA,[according to whom?][189] estimations of 30,000 Ukrainian casualties are unsupported;[27] his estimates are 2,000–3,000 Ukrainians killed in Volhynia and 10,000–15,000 in all of the territories covered by the conflict in 1943–1947. He states that most of the Ukrainian casualties occurred within the post-war Polish borders (8,000–10,000, including 5,000–6,000 Ukrainians killed in 1944–1947).[27]

The historian Timothy Snyder considers it likely that the UPA killed as many Ukrainians as it killed Poles, because local Ukrainians who did not adhere to its form of nationalism were considered traitors.[7]

Responsibility

The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), of which the UPA had become the armed wing, promoted the removal, by force if necessary, of non-Ukrainians from the social and economic spheres of a future Ukrainian state.[190]

The OUN adopted in 1929 the Ten Commandments of the Ukrainian Nationalists to which all of its members were expected to adhere. They stated, "Do not hesitate to carry out the most dangerous deeds" and "Treat the enemies of your nation with hatred and ruthlessness".[191]

The decision of ethnic cleansing of the area east of the Bug River was taken by the UPA early in 1943. In March 1943, the OUN(B) (specifically Mykola Lebed[192]) imposed a collective death sentence of all Poles living in the former east of the Second Polish Republic, and a few months later, local units of the UPA were instructed to complete the operation soon.[193] The decision to eliminate the territory's Poles determined the course of future events. According to Timothy Snyder, the ethnic cleansing of the Poles was exclusively the work of the extremist Bandera faction of the OUN, rather than its Melnyk faction or other Ukrainian political or religious organizations. Polish investigators claim that the OUN-B central leadership decided in February 1943 to drive all Poles out of Volhynia to obtain an "ethnically pure territory" in the postwar period. Among those who were behind the decision, Polish investigators singled out Dmytro Klyachkivsky, Vasyl Ivakhov, Ivan Lytvynchuk and Petro Oliynyk.[194]

Ethnic violence was exacerbated with the circulation of posters and leaflets inciting the Ukrainian population to murder Poles and "Judeo-Muscovites" alike.[195][196][197]

Taras Bulba-Borovets, the founder of the UPA, criticized the attacks as soon as they began:

The axe and the flail have gone into motion. Whole families are butchered and hanged, and Polish settlements are set on fire. The "hatchet men", to their shame, butcher and hang defenceless women and children.... By such work Ukrainians not only do a favor for the SD [German security service], but also present themselves in the eyes of the world as barbarians. We must take into account that England will surely win this war, and it will treat these "hatchet men" and lynchers and incendiaries as agents in the service of Hitlerite cannibalism, not as honest fighters for their freedom, not as state-builders.[198]

According to prosecutor Piotr Zając, the Polish Institute of National Remembrance in 2003 considered three different versions of the events in its investigation:[199]

- The Ukrainians at first planned to chase the Poles out, but events got out of hand over time.

- The decision to exterminate the Poles came directly from the OUN-UPA headquarters.

- The decision to exterminate the Poles can be attributed to some of the leaders of the OUN-UPA in the course of an internal conflict in the organisation.

The IPN concluded that the second version to be the most likely.[200]

In October 1943 the OUN issued a communication (in Ukrainian only) that condemned the "mutual mass murders" of Ukrainians and Poles.[201]

Reconciliation

In 1944–1945, the UPA and Home Army initiated a ceasefire and orders to cease any actions against civilians, and with mediation of Orthodox and Roman Catholic clergy a meeting was arranged between commanders of both formations. The agreement resulted in joint UPA-Home Army operation against NKVD prison in Hrubieszów. By 1948, both organisations largely ceased to exist with its members arrested or escaping to the West.[202]

The question of official acknowledgment of the ethnic cleansing remains a matter of discussion between Polish and Ukrainian historians and political leaders. Efforts are ongoing to bring about reconciliation between Poles and Ukrainians regarding the events. The Polish side has made steps towards reconciliation; in 2002 President Aleksander Kwaśniewski expressed regret over the resettlement program, known as Operation Vistula: "The infamous Operation Vistula is a symbol of the abominable deeds perpetrated by the communist authorities against Polish citizens of Ukrainian origin." He stated that the argument that "Operation Vistula was the revenge for the slaughter of Poles by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army" in 1943–1944 to be "fallacious and ethically inadmissible" by invoking "the principle of collective guilt".[203] The Ukrainian government has not yet issued an apology.[204][205]

On 11 July 2003, Presidents Aleksander Kwaśniewski and Leonid Kuchma attended a ceremony held in the Volhynian village of Pavlivka (previously known as Poryck),[206] where they unveiled a monument to the reconciliation. The Polish president said that it is unjust to blame the entire Ukrainian nation for these acts of terror: "The Ukrainian nation cannot be blamed for the massacre perpetrated on the Polish population. There are no nations that are guilty.... It is always specific people who bear the responsibility for crimes".[207]

Between 2015 and 2018 a Forum of Polish and Ukrainian Historians was jointly researching archival documents, including new archives declassified by Ukrainian government. Another joint effort resulted in publishing multi-volume book "Poland and Ukraine in the 1930s–1940s: Unknown documents from the secret service archives"[208] first volume of which was published in 1998 and 10th in 2020. The cooperation is led on government level by Institute of National Remembrance (Poland) and Sectoral State Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine (HDA SBU).[209]

In 2016 Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko visited Warsaw and paid tribute to the victims at the Volhynia monument.[210]

In 2017, Ukrainian politicians banned the exhumation of the remains of Polish victims in Ukraine killed by the UPA in revenge for Polish demolition of the illegal UPA monument in the village of Hruszowice.[211][212]

In 2018, Polish president Andrzej Duda refused to participate in a joint ceremony commemorating the 75th anniversary of the massacres with the Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko and instead travelled to Lutsk to hold a separate event.[213][clarification needed]

In May 2023, Ukraine's Rada chairman Ruslan Stefanchuk spoke in front of the Polish Sejm, where he expressed sympathy to the victims of the massacre, their families and descendants and called for reconciliation. Stefanchuk promised continued joint work on explaining the details of the tragedy. The speech was described as Polish minister of foreign affairs Zbigniew Rau as "promising".[214]

In June 2023 archeological excavations started in a former village of Puzhniki in Volhynia by a group of Polish scientists to identify possible mass graves of the massacre victims.[215]

In July 2023, Polish president Andrzej Duda and Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky jointly paid tribute to the victims in Lutsk, administrative capital of the Volhynia region, attended a mass in local church on the 80th anniversary of the tragedy.[216] A joint declaration on the need of reconciliation was also signed by heads of Roman Catholic Church in Poland, archbishop Stanisław Gądecki, and Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church Sviatoslav Shevchuk.[217] Polish Sejm adopted a resolution commemorating the victims, blaming OUN and UPA, praising rescue offered to the Poles by some Ukrainian individuals, calling for reconciliation recognizing guilt of the perpetrators and highlighting the need for exhumations.[218]

Classification as genocide

Scholarly consensus

UCLA historian Jared McBride, an expert in the region and in the Holocaust, writing in Slavic Review in 2016, said there is a "scholarly consensus that this was a case of ethnic cleansing as opposed to genocide".[219]

Writing in 2004, historian Antony Polonsky, an expert on the Holocaust and Polish Jewish history, said that the "[massacres'] goal was not so much genocide as it was to force the local Polish population to leave."[220]: 290

Historian Per Anders Rudling wrote in 2006 that the goal of the OUN-UPA was not the extermination of Poles but ethnic cleansing of the region to attain an ethnically homogeneous state. The goal was thus to prevent a repeat of 1918–20, when Poland crushed Ukrainian independence, as the Polish Home Army was attempting to restore the Polish Republic in its pre-1939 borders.[32]

According to a 2010 conference paper by Ivan Katchanovski, the mass killings of Poles in Volhynia by the UPA cannot be classified as a genocide because there is no evidence that the UPA intended to annihilate entire or significant parts of the Polish nation, the UPA action was mostly limited to a relatively small area and the number of Poles killed was quite a small fraction of the prewar Polish population in both the territories in which the UPA operated and of the entire Polish population in Poland and Ukraine.[175]

In 2016, Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe, author of a scholarly biography of Bandera, argued that the killings were ethnic cleansing rather than genocide. Rossoliński-Liebe sees "genocide", in this context, as a word that is sometimes used in political attacks on Ukraine.[221]

However, historian Grzegorz Motyka, an expert on Polish-Ukrainian issues, argued in 2021 that "although the anti-Polish action was an ethnic cleansing, it also meets the definition of genocide".[222]

Polish view

The Polish Institute of National Remembrance investigated the crimes committed by the UPA against the Poles in Volhynia, Galicia and prewar Lublin Voivodeship and collected over 10,000 pages of documents and protocols. The massacres were described by the commission's prosecutor, Piotr Zając, as bearing the characteristics of a genocide: "there is no doubt that the crimes committed against the people of Polish nationality have the character of genocide".[223] The Institute of National Remembrance stated:

The Volhynian massacres have all the traits of genocide listed in the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, which defines genocide as an act "committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such".[224]

Some participants at a conference on the massacres held in 2008 by the Institute used the word "Zagłada", originally applied to the Final Solution, to describe them.[225]

On 15 July 2009, the Sejm of the Republic of Poland unanimously adopted a resolution regarding "the tragic fate of Poles in Eastern Borderlands". The text of the resolution states that July 2009 marks the 66th anniversary "of the beginning of anti-Polish actions by the Organization of Ukrainian nationalists and the UPA on Polish Eastern territories – mass murders characterised by ethnic cleansing with marks of genocide".[226] On 8 July 2016, the Sejm passed a resolution declaring 11 July a National Day of Remembrance of the victims of the Genocide of the Citizens of the Polish Republic committed by Ukrainian Nationalists and formally called the massacres a genocide.[227][228]

A number of Polish authors, especially on the right, have labeled the Volhynia massacres worse than Nazi or Soviet atrocities in terms of their brutality, though not in scale, as so many of the victims were tortured and mutilated.[229]

Ukrainian view

In Ukraine, the events are called "Volhynia tragedy".[230][4] Coverage in textbooks may be brief and/or euphemistic.[231] Some Ukrainian historians accept the genocide classification, but argue that it was a "bilateral genocide" and that the Home Army was responsible for crimes against Ukrainian civilians that were equivalent in nature.[229]

Many Ukrainians perceived the 2016 resolution as an "anti-Ukrainian gesture" in the context of Vladimir Putin's attempts to use the Volhynia issue to divide Poland and Ukraine in the context of the Russian–Ukrainian war. In September 2016, the Verkhovna Rada passed a resolution condemning "the one-sided political assessment of the historical events" in Poland.[229] According to Ukrainian historian Andrii Portnov, the classification as genocide has been strongly supported by Poles who were expelled from the east and by parts of the Polish right-wing politics.

Ukrainian historians called for assessing the massacres in the historical context, pointing out historical repressions against Ukrainian population and forced polonization in pre-war Poland.[214]

Ukrainian historian Yuri Shapoval openly speaks about the "Volhynia Slaughter" and calls for increased recognition of the massacre inside Ukraine, pointing out very complex ethnic composition of these territories, mutual historical resentments and incitement by external parties, Soviets, Germans and Polish government on exile.[208]

In popular culture

In 2009, a Polish historical documentary film Było sobie miasteczko... was produced by Adam Kruk for Telewizja Polska which tells the story of the Kisielin massacre.[232]

The massacre of Poles in Volhynia was depicted in the 2016 movie Volhynia, which was directed by the Polish screenwriter and film director Wojciech Smarzowski.

See also

- Historiography of the Massacre of Poles in Volhynia

- 27th Polish Home Army Infantry Division

- Baligród massacre

- Bloody Sunday on Volhynia

- Budy Ossowskie massacre

- Chodaczków Wielki massacre

- Chrynów massacre

- Dominopol massacre

- Gaj massacres

- Głęboczyca massacre

- Gurów massacre

- Hurby massacre

- Huta Pieniacka massacre

- Janowa Dolina massacre

- Kisielin massacre

- Koliyivschyna

- Korosciatyn massacre

- Marianna Dolińska

- Massacre of Ostrówki

- Massacre of Wola Ostrowiecka

- Muczne massacre

- Operation Vistula

- Palikrowy massacre

- Parośla I massacre

- Pidkamin massacre

- Poryck Massacre

- Przebraże Defence

- Wiązownica massacre

- Wiśniowiec massacres

- Zagaje massacre

- List of massacres in Ukraine

Notes

- ^ Also referred to by several other names, which may reflect either full or partial territorial scope: the Volhynian massacre (Polish: rzeź wołyńska, lit. 'Volhynian slaughter'), the Volhynian tragedy (Ukrainian: Воли́нська траге́дія, romanized: Volynsʹka trahediya), the Volhynian–Galician massacre, the Anti-Polish Operation (Polish: akcja antypolska; Ukrainian: антипольська акція, romanized: antypolʹsʹka aktsiya).

References

- ^ Ferguson, Niall (2006). The War of the World: Twentieth-Century Conflict and the Descent of the West. Penguin Publishing. p. 455. ISBN 1-59420-100-5.

- ^ a b Hryciuk & Palski 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Kulińska 2010, p. 27–30.

- ^ a b Andrii Portnov (16 November 2016). "Clash of victimhoods: The Volhynia Massacre in Polish and Ukrainian memory".

- ^ "OUN i UPA od walk do ludobójstwa". Rzeczpospolita (in Polish).

Ogromne straty ze strony OUN-UPA poniósł Kościół rzymskokatolicki, naturalny u wierzących chrześcijan szacunek dla duchownych, świątyń, cmentarzy i religijnych praktyk został bowiem w duszach nacjonalistów ukraińskich zrujnowany.

[The Roman Catholic Church suffered huge losses from the OUN-UPA; the natural respect among Christian believers for clergy, temples, cemeteries and religious practices was ruined in the souls of Ukrainian nationalists.] - ^ Institute of National Remembrance. "What were the Volhynian Massacres?". Volhynia Massacre. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ a b c Timothy Snyder (24 February 2010). "A Fascist Hero in Democratic Kiev". The New York Review of Books. NYR Daily.

Bandera aimed to make of Ukraine a one-party fascist dictatorship without national minorities.... UPA partisans murdered tens of thousands of Poles, most of them women and children. Some Jews who had taken shelter with Polish families were also killed.

- ^ a b J. P. Himka. Interventions: Challenging the Myths of Twentieth-Century Ukrainian history. University of Alberta. 28 March 2011. p. 4, reproduced in The Convolutions of Historical Politics, edited by Alexei Miller and Maria Lipman, 211–238. Budapest and New York: Central European University Press, 2012, p. 214

- ^ Ahonen, Pertti (2008). Peoples on the Move: Population Transfers and Ethnic Cleansing Policies During World War II and Its Aftermath. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 99.

- ^ a b c Motyka 2011, p. 447.

- ^ Ferguson, Niall (2006). The War of the World: Twentieth-Century Conflict and the Descent of the West. Penguin Publishing. p. 455. ISBN 1-59420-100-5.

- ^ Snyder 2003b, p. 197–234.

- ^ Komański & Siekierka 2006, p. 203.

- ^ Motyka 2006, p. 305-306.

- ^ Motyka 2006, p. 306-307.

- ^ Motyka 2006, p. 307-308.

- ^ Motyka 2006, p. 327-360.

- ^ Motyka 2006, p. 412.

- ^ Snyder 2003a, p. 175.

- ^ Burds, Jeffrey (1999). "Comments on Timothy Snyder's article, "To Resolve the Ukrainian Question once and for All: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ukrainians in Poland, 1943–1947"". Journal of Cold War Studies. 1 (2). (1) Chronology.

The more I study Galicia, the more I come to the conclusion that *the defining issue was not Soviet or German occupation and war, but rather the civil war between ethnic Ukrainians and ethnic Poles.

- ^ Motyka 2006, p. 366-367.

- ^ Motyka 2006, p. 369-376.

- ^ Motyka 2006, p. 377.

- ^ Motyka 2006, p. 378.

- ^ Motyka 2006, p. 377-378.

- ^ Motyka 2006, p. 410-411.

- ^ a b c Motyka 2011, p. 448.

- ^ McBride 2016a, p. 641.

- ^ "Sejm przyjął uchwałę dotyczącą Wołynia ze stwierdzeniem o ludobójstwie". Rzeczpospolita (in Polish). Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ^ McBride 2016a, p. 631-632.

- ^ Subtelny 1988, p. 429.

- ^ a b c d e f A. Rudling. Theory and Practice. Historical representation of the wartime accounts of the activities of OUN-UPA (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists-Ukrainian Insurgent Army). East European Jewish Affairs. Vol. 36. No. 2. December 2006. pp. 163–179.

- ^ Motyka 2006, p. 36.

- ^ Motyka 2006, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Rudling, Per A. (November 2011). "The OUN, the UPA and the Holocaust: A Study in the Manufacturing of Historical Myths". Number 2107. University of Pittsburgh: The Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Studies. p. 3 (6 of 76 in PDF). ISSN 0889-275X.

- ^ Bohdan Budurowycz. (1989). Sheptytski and the Ukrainian National Movement after 1914 (chapter). In Paul Robert Magocsi (ed.). Morality and Reality: The Life and Times of Andrei Sheptytsky. Edmonton, Alberta: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, University of Alberta. p. 57.

- ^ Subtelny 1988, p. 444.

- ^ a b Subtelny 2000, p. 430.

- ^ Timothy Snyder. (2005). Sketches from a Secret War: A Polish Artist's Mission to Liberate Soviet Ukraine. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 167

- ^ Subtelny 2000, p. 432The remaining Orthodox churches were forced to use the Polish language in their sermons. In August 1939, the last remaining Orthodox church in the Volhynian capital of Lutsk was converted to a Roman Catholic church by a decree of the Polish government.

- ^ a b Snyder 2003b, p. 202.

- ^ Timothy Snyder. (2005). Sketches from a Secret War: A Polish Artist's Mission to Liberate Soviet Ukraine. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 32–33, 152–162

- ^ Сивицький, М. Записки сірого волиняка Львів 1996 с. 184

- ^ Motyka 2006, p. 58.

- ^ Lidia Głowacka, Andrzej Czesław Żak, Osadnictwo wojskowe na Wolyniu w latach 1921–1939 w swietle dokumentów centralnego archiwum wojskowego Archived 2014-08-15 at the Wayback Machine (Military Settlers in Volhynia in the years 1921–1939), PDF, pp. 143 (4 / 25 in PDF), 153 (14 / 25 in PDF). "Mimo ogromnych trudności, kryzysu gospodarczego na początku lat 30. i złożonej sytuacji politycznej na tym terenie, osadnicy zdołali zagospodarować znaczne obszary ziemi i stworzyć od podstaw wiele osad z nowoczesną – jak na owe czasy –infrastrukturą. W 1939 r. na Wołyniu mieszkało około 17,7 tys. osadników wojskowych i cywilnych w ponad 3,500 osad."

- ^ In one of many such incidents, the Papal Nuncio in Warsaw reported that Polish mobs attacked Ukrainian students in their dormitory under the eyes of Polish police, a screaming Ukrainian woman was thrown into a burning Ukrainian store by Polish mobs and a Ukrainian seminary was destroyed during which religious icons were desecrated and eight people were hospitalized with serious injuries and two killed. See Burds 1999.

- ^ Burds 1999.

- ^ According to official data, 20 communists were injured during police actions in 1935, and in one case policemen wounded at least seven people while being assaulted by a crowd armed with sickles and clubs. The communists retaliated against those who failed to participate in strikes. From: Timothy Snyder (2007). Sketches from a Secret War: A Polish Artist's Mission to Liberate Soviet Ukraine. Yale University Press. pp. 137, 142.

- ^ a b c d e f Snyder 1999.