Van Ness Bus Rapid Transit

| Van Ness Bus Rapid Transit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A southbound Muni bus at Fell Street in April 2022 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other name(s) | Van Ness Improvement Project | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | San Francisco, California, United States | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Termini |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | sfmta | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Bus rapid transit | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System | San Francisco Municipal Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Services | Muni: 30X, 47, 49, 76X, 79X, 90 Golden Gate Transit: 101, 130, 150 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | April 1, 2022[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 1.96 miles (3.15 km) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | Parallel overhead lines, 600 V DC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Van Ness Bus Rapid Transit is a bus rapid transit (BRT) corridor on Van Ness Avenue in San Francisco, California, United States. The 1.96-mile (3.15 km) line, which runs between Mission Street and Lombard Street, has dedicated center bus lanes and nine stations. It was built as part of the $346 million Van Ness Improvement Project, which also included utility replacement and pedestrian safety features. Van Ness Bus Rapid Transit is used by several San Francisco Municipal Railway (Muni) lines including the 49 Van Ness–Mission, as well as three Golden Gate Transit routes.

Public transit on Van Ness Avenue began with streetcar service in 1915. It was replaced by trolleybuses in 1950–51, with diesel bus routes later added. Planning for a rail line on the corridor began in 1989 with the passage of a ballot measure. By 1995, it was to be the last of four major rail corridors constructed in the city. The planned mode was replaced with BRT in 2003, with studies and environmental analysis lasting the next decade. Construction began in June 2016; the planned completion in 2019 was delayed several times. The corridor opened to service on April 1, 2022.

Design

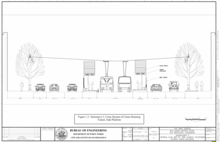

The Van Ness BRT corridor is 1.96 miles (3.15 km) long, running north–south between Lombard Street and Mission Street.[2]: 2–9 Van Ness Avenue has six travel lanes on this section – two general-purpose lanes in each direction, plus center-running red bus lanes. Nine stations are located along the corridor, each with side platforms on the right side of buses. A landscaped center median is located between the bus lanes except at stations. The northbound bus lane exits at Filbert Street, with a marked transition for buses to move to the curb lane.[3] The red lanes on Van Ness are poured red concrete, rather than paint or thermoplastic markings applied over conventional pavement, for increased durability. A 6-inch-thick (150 mm) layer of reinforced concrete was poured as the foundation, followed by a curing compound. The red concrete was then poured, with dowel baskets to join adjacent slabs, then topped with a color hardener layer. The finished lane pavement has a compressive strength of 8,000 pounds per square inch (55,000 kPa), 60% stronger than a typical roadway, extending its life.[4]

Services and stations

All services using Van Ness BRT operate only part of their length on the BRT lanes; they operate in mixed traffic or on separately installed bus lanes off the Van Ness corridor. SFMTA normally operates two primary routes along the full length of the BRT corridor – 47 Van Ness and 49 Van Ness-Mission – with combined headways as low as 3.5 minutes; several other routes (including the 30X Stockton Express, 76X Marin Headlands, 79X Arena Express, and 90 San Bruno Owl) operate on part or all of the corridor at lower frequencies.[5]: 2–17 In April 2020, SFMTA suspended the 47 Van Ness bus route due to the COVID-19 pandemic in California, leaving only route 49 running the full length of Van Ness BRT.[6] Golden Gate Transit (GGT) operates three routes along the Van Ness BRT corridor: 101, 130 (formerly 30), and 150 (formerly 70).[7]: 13, 32 GGT buses use only the seven stops from Union to Eddy, as they run on Golden Gate Avenue and McAllister Street to reach downtown San Francisco.[7]: 38 [8]

The Van Ness BRT alignment has nine stations named after cross streets. Market Street station is located at Van Ness station, providing transfer to Muni Metro, while a transfer to the Geary BRT service is available at Geary–O'Farrell station.[9]: Fig.2-2

| Street | Image | Routes | Muni connections |

|---|---|---|---|

| Union |

|

Muni: (30X), 47, 49, 76X, 79X, 90 GGT: 101, 130, 150 |

|

| Vallejo |

|

Muni: (30X), 47, 49, (76X), 79X, 90 GGT: 101, 130, 150 |

— |

| Jackson |

|

Muni: 47, 49, 76X, 79X, 90 GGT: 101, 130, 150 |

|

| Sacramento |

|

Muni: 47, 49, 76X, 79X, 90 GGT: 101, 130, 150 |

|

| Sutter |

|

Muni: 47, 49, 76X, 79X, 90 GGT: 101, 130, 150 |

— |

| Geary–O'Farrell |

|

Muni: 47, 49, 79X, 90 GGT: 101, 130, 150 |

|

| Eddy |

|

Muni: 47, 49, 79X, 90 | |

| McAllister |

|

Muni: 47, 49, 79X, 90 | |

| Market (Van Ness station) |

|

Muni: 47, 49, 79X, 90 | |

| Muni routes 47, 76X, and 79X are suspended. (Routes in parentheses pass the stop but do not serve it.) | |||

Cost

As rated in November 2014 by the Federal Transit Administration (FTA), the project was planned to cost $162.7 million, with approximately $75 million to be provided as federal funding under the Small Starts Project Development Program.[10] In December 2016, the FTA awarded the $75 million Small Starts grant.[11] The entire Van Ness Improvement Project had a budget of $309 million when construction began.[12]: 25 By 2022, the budget for only the transit improvements had grown to $169.6 million, with a total project cost of $346 million.[13][12]: 7 Part of the increased cost was covered by contingency funds in the original funding; the FTA also awarded an additional $21.9 million to the project in 2021 using funds allotted from the American Rescue Plan.[14]

A 2021 civil grand jury report determined the planning process had failed to account for the location and future maintenance of underground utility lines; because existing water and sewer lines were buried under the center of Van Ness, they had to be relocated curbside to avoid future disruption of BRT service when these utilities required maintenance. The choice of center bus lanes, rather than side lanes, also required substantial reconfiguration and temporary de-energization of the trolleybus wires. The report found that the choice of center lanes increased the cost and complexity of the project, as well as the overall benefits.[12]: 7–9 Although the general position of the existing utility lines was known as early as 2006, detailed survey maps and routing were not developed until after the project had started construction, and the task of determining exact utility routing fell on the construction contractor rather than SFMTA, exceeding the contractor's intended scope of responsibilities and causing project cost and schedule overruns.[12]: 10–11

Public art

In August 2013, a selection panel of the San Francisco Arts Commission (SFAC) recommended the proposal from Cuban-born artist Jorge Pardo for consideration by the full SFAC over competing proposals from Norie Sato and Janet Zweig for a series of three sculptures that would be installed at the Market, Sutter and Union stations.[15] Pardo presented a formal proposal in 2015, calling for a series of caged weathering steel sculptures, lit from within.[16] According to Pardo, the three 20 ft-tall (6.1 m) sculptures were intended to be "urban coastal redwood[s] ... made of steel, light and weather". The SFAC formally selected Pardo in September 2015.[17] By 2017, the proposed work and location had been consolidated to a single installation at the two McAllister station platforms; each platform would have thirteen steel-and-polycarbonate light sculptures, distinguished by a warm or cool palette.[18] The Arts Commission authorized a budget of $815,000 for the work on October 2, 2017.[19] This final design subsequently was moved to the Geary–O'Farrell station, with the cool palette on the southbound platform and the warm palette on the northbound platform.[20][21]

Criticism

Some automobile drivers complained about possible changes in traffic patterns and loss of automobile parking along the corridor.[22] Concerns that trees would be removed were met with plans to plant more trees on the route.[23] Residents supportive of the project complained about continued delays in completing the project, and that the project took longer to complete than other similar projects in other cities because the SFMTA did not close the street to automobile traffic during construction.[24] Businesses along Van Ness complained of lost customers due to construction disruption and the delays in completion.[24] Mayor Ed Lee announced a Construction Mitigation Program (CMP) in September 2017 to provide grants to businesses affected by transit construction, but the focus of that program primarily focused on Union Square businesses and Central Subway construction. CMP funds were not available until November 2019, and were not opened for Van Ness businesses until September 2020.[25]

The project has been criticized for using 6-inch (150 mm) platforms, the standard sidewalk height, instead of 14-inch (360 mm) platforms that would match the level of the bus floor to allow for level boarding.[26][27] Field tests indicated that interference with wheel lug nuts would create a gap at least 5 in (130 mm) wide between the edge of a 14-inch-high platform and the boarding doors, and bridge plates would be required at middle doors to meet ADA standards for level boarding; the added complexity could impact vehicle reliability. In addition, because the buses would also operate outside the Van Ness BRT corridor, they would continue to need to be equipped with boarding ramps at the front door for regular curbside service.[28]

Concrete poles

The original concrete poles built to support the overhead electrical supply lines for the streetcars in 1914 were moved onto the sidewalks in 1936 to accommodate the widening of Van Ness.[29]: 1–2 Since then, the poles have deteriorated due to extra loads from additional wires (added for the electrical return path when the lines were converted to trolleybus service) and modified catenary geometry, exhibiting significant spalling and cracking. In some cases, Muni has supplemented the original concrete poles by moving wires onto adjacent, modern metal poles. By the mid-1980s, records show the city was concerned the original poles could not support their existing loads and starting in 1997, began replacing missing cast iron pole bases with fiberglass replicas.[29]: 1–3 A 2009 evaluation of the original 1914/36 poles concluded they could not be rehabilitated and retrofitted for use on the modern BRT line because of their shape, height, and inadequate foundation.[29]: 1–4 [23] A separate report determined the original trolley poles were not eligible for retention on a historical basis due to their loss of physical integrity.[30]: 60

The city's Historic Preservation Commission provided conditional approval to remove the original 1914/1936 trolley poles and streetlamps in November 2015, but preservationists were concerned over the loss of the Van Ness "Ribbon of Light" and three prominent organizations formed the "Coalition to Save the Historic Streetlamps of Van Ness Avenue" in 2016.[23][31] The Board of Supervisors unanimously passed a resolution on September 20, 2016, urging SFMTA to "make all efforts to preserve the historic character of the Van Ness Corridor".[32] As a result, SFMTA approved the installation of 350 vintage-style light fixtures at a cost of $18,500 each, adding $6.5 million to the project cost. Ironically, because the proposed fixtures are insufficiently faithful to the original design, the Historic Preservation Commission required that modern-style light poles be used in the Civic Center Historic District instead as "they don't create a lot of visual clutter".[33] As a compromise, four poles were retained and restored in front of San Francisco City Hall and War Memorial Plaza.[32][34][33]

History

Early streetcar and bus service

The San Francisco Municipal Railway was formed in 1909 and opened its first line on Geary Boulevard in 1912. A bond issue to build routes serving the 1915 Panama–Pacific International Exposition was approved in 1913.[35]: 35 Construction work started on a Van Ness Avenue line on April 6, 1914; electrical and track work were completed by August 15 of that year, earning the contractors a $15,000 bonus (equivalent to $340,000 in 2023).[30]: 22 As completed, the line on Van Ness included 259 concrete poles to support the overhead electrical supply wires, and streetlights were added to the poles one year later.[29]: 1–2

Streetcar service on Van Ness Avenue began on August 15, 1914. The H Potrero ran the full length of Van Ness Avenue between Bay Street and Market Street, while the D Geary–Van Ness ran on Van Ness Avenue north of Geary Street.[35]: 38 Service on the F Stockton route, which used Van Ness Avenue between North Point Avenue and Chestnut Street, began on December 29, 1914.[35]: 43 Several other routes also ran on Van Ness for short periods: G Exposition and I Exposition in 1915, J Exposition in 1915–16, J Church in 1917–18, K Ingleside in 1918, and E Union Street and O Van Ness in 1932.[36]

Van Ness, famed as the widest street in the city and for its row of auto dealerships, also became busy with automobile traffic, as it became part of U.S. Route 101 in 1926.[30]: 23, 31 In 1934, with the opening of the Golden Gate Bridge imminent, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors proposed to expand surface streets to facilitate automobile traffic, including widening Van Ness from Market to Bay.[37]: 73 The widening of the roadway was carried out in 1936 by narrowing the sidewalks.[30]: 29 Soon after, the center-running streetcars on Van Ness were faulted for potentially holding up automobiles by their frequent stops.[38] Streetcar service was discontinued on Van Ness — D and H in 1950, and F in 1951 — and the overhead lines were reused for trolleybus service.[36][35]: 180 A median with trees was built down the center of Van Ness.[30]: 31

The 47 Potrero (later 47 Van Ness) trolleybus service that replaced the H Potrero became the primary transit service on Van Ness Avenue for the next several decades, with the 45 Van Ness (the former D) supplementing it between Union Street and Sutter Street, and the 30 Stockton (the former F) between North Point and Chestnut streets. Route 30X Freeway Express (now 30X Marina Express) began using Van Ness Avenue between Broadway and Chestnut Street in 1956. Golden Gate Transit bus service to San Francisco began in January 1972. Civic Center routes used Van Ness Avenue between Lombard Street and McAllister Street, while Financial District routes used it between Lombard Street and North Point Street.[39]

Route 76 Fort Cronkite (now 76X Marin Headlands Express) began intermittent service on Van Ness Avenue in 1976, while the 42 Downtown Loop began operating along the full length of Van Ness Avenue on September 10, 1980.[36][40] The 49 Van Ness–Mission trolleybus route began operation on August 24, 1983.[41] Route 45 was rerouted off Van Ness Avenue on October 1, 1988, becoming the 45 Union/Stockton.[40] The 47 and the western portion of the 42 were merged into the 47 Van Ness on June 9, 2001.[42]

Bus rapid transit planning

The Proposition B sales tax expenditure plan, approved in 1989, included funding for "transit service improvements on Van Ness Avenue".[43] The transit expansion part of the expenditure plan formed the basis of the 1995 Four Corridor Plan by the San Francisco County Transportation Authority (SFCTA), which planned for rail expansions along four priority corridors including Van Ness.[44] The other three corridors included the Bayshore Corridor, which was implemented as the T Third Street Muni line; a proposed rail line along Geary Boulevard, which ultimately became the Geary Bus Rapid Transit project; and a third corridor to North Beach, implemented as the Central Subway project. The Van Ness corridor was to be the last of the four corridors, beyond the twenty year planning timeline of Proposition B.[45] Under the Four Corridor plan, a rail line was to be built along Van Ness Avenue and Mission Street from Aquatic Park to 16th Street Mission station, with a subway section between Market and Pacific streets.[44]: 10

In 2003, with Proposition B expiring in 2010, Proposition K was passed to provide additional sales tax funds. Its specified expenditure plan included BRT on the Geary and Van Ness corridors; these were identified as part of the New Expenditure Plan in the SFCTA Countywide Transportation Plan of 2004.[46][47]: 67, 113 Collectively, the Geary and Van Ness corridors had more than 200,000 automobile-based person-trips per day, with BRT implementation anticipated to remove approximately 4,500 vehicles at peak periods.[47]: 72 For Van Ness, the project was planned to include transit signal priority.[47]: 109 The SFCTA began to formally plan the project in 2004, with revenue service then planned for 2012.[48] A feasibility study was completed in 2006.[5] The proposed projects on Van Ness and Geary were anticipated to have short construction times (between 18 and 24 months) and lower costs than rail lines.[49]

The feasibility study was followed by a Technical Memorandum in 2008 and the Draft Environmental Impact Statement/Environmental Impact Report (DEIS) in 2011.[50][2][9] The DEIS identified three possible designs: curb lanes, median lanes with side platforms, and median lanes with a center island platforms.[9] The proposed service was estimated to reduce overall travel time by one-third and increase ridership by approximately the same proportion.[51]

Alternative 3 – center median lanes with side platforms was identified as the locally-preferred option in 2013 and selected for implementation.[52]: 10–27 The analysis showed that dedicated center lanes for BRT coupled with restricted left turns provided the greatest reduction in travel time compared with existing conditions, with up to 930 passengers per hour per lane with BRT versus 680 via private automobile.[52]: 10–5, 15 Alternative 4 (center platforms), which was not chosen, had carried an additional risk for vehicle procurement. Buses with doors on both sides would be needed, which would be a custom order as no trolleybus was available in North America with dual-sided boarding.[52]: 10–26

The Final Environmental Impact Statement was released in July 2013, and approved by the SFCTA and SFMTA that September.[53] Changes from the DEIS included several platform locations and elimination of most left turns on Van Ness.[9] Both agencies also approved the addition of an optional southbound platform at Vallejo Street (the northbound platform was already added in the LPA).[53] The Federal Transit Administration approved the FEIS in December 2013.[53] The "lengthy planning, review, and public-participation process" in 2014 was faulted for causing delays in BRT implementation, as opposition to the removal of an automobile lane and impacts to parking were not offset by a local working example demonstrating its benefits.[54] In addition, local opposition to the Van Ness BRT project included public hearings over median changes and tree removal, despite promises to replace 200 mature trees with 400 saplings.[55] Addenda regarding parking loss and street tree removal were published in 2014 and 2016.[53] By 2015, the new BRT service was scheduled to open in early 2019.[56]

Construction and opening

The first phase of construction involved the removal and replacement of underground water and sewer lines, some of which dated back to the 19th century. Half of the road width was closed at a time, with construction proceeding south simultaneously from Lombard Street and Sutter Street. This first phase was originally expected to last two years; BRT construction in the second phase was to last one year, while operator training, tree planting, and sidewalk work would last two months.[57]

Nine bus stops were eliminated on June 4, 2016, to speed up buses during construction and match the BRT stop spacing.[58] General traffic was reduced from three lanes per direction to two in October 2016, and most left turns were eliminated in November.[59][60] The one-way Franklin and Gough streets to the west received traffic signal upgrades to accommodate traffic diverted from Van Ness.[61] A groundbreaking ceremony was held on March 1, 2017, with completion then still planned for 2019.[62]

The median was cleared of trees and shrubs in June 2017, and utility work began that August. By October 2017, wet weather and contractor issues had delayed planned completion by six months to mid-2020.[63] An additional five-month delay due to unexpected abandoned utilities was announced in April 2018.[64] Items uncovered during utility work covered a broad range of history, from Ohlone artefacts to abandoned fiber optic cables originally placed during the dot-com boom.[65] Construction was 21% complete by mid-2018.[66] By early 2019, the project was 27% complete; continued utility and contractor conflicts delayed expected completion to late 2021.[67] The first half of utility reconstruction was completed in June 2019, with the second half finished in mid-2020.[68][69]

Construction of the second phase began in September 2020.[70] Excavation for the second phase uncovered tracks originally used for the California Street Cable Railroad, as well as original Belgian block stones from the early 20th century.[71][72] Further delays in 2020 pushed the estimated completion to 2022.[73] The first red concrete was poured for the BRT lanes on November 10, 2020, and hundreds of trees were planted along Van Ness at approximately the same time. Species planted include lemon-scented gum along the median and London plane, Brisbane box, and palm trees along the sidewalk.[74][75][76] The red concrete pour was completed in July 2021, and work continued on landscaping and median construction.[77][78][79]

Testing with Muni and Golden Gate Transit vehicles began on January 12, 2022, followed by driver training.[80][81] Revenue service began on April 1, 2022.[1][82] By the end of the month, northbound travel times had decreased by nine minutes – 35% – while ridership on route 49 had increased by 13%. Further decreases in travel time were expected as transit signal priority was activated and adjusted.[83] Route 49 remained temporarily operated solely by motorbuses – as had been the case during BRT construction, since 2016 – pending operations changes enabling its runs to be moved back to Potrero Division.[84] Two trolleybus-operated supplementary runs (not shown in public schedules) operating in the weekday midday period only began operation on July 25,[85] but regular, all-day, seven-days-a-week use of trolleybuses on route 49 did not resume until January 2023 – and temporarily covering only one-quarter of the route's runs.[86] In September 2024, the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy rated Van Ness BRT as "Silver" on its BRT Standard scale.[87]

See also

References

- ^ a b "BRT Service on Van Ness to Begin Tomorrow" (Press release). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. March 31, 2022.

- ^ a b "2: Project Alternatives". Draft Environmental Impact Statement / Environmental Impact Report: Van Ness Avenue Bus Rapid Transit Project (Report). San Francisco County Transportation Authority. October 2011.

- ^ "Appendix A: Alignment Plans: LPA Alternative" (PDF). Final Environmental Impact Statement / Environmental Impact Report: Van Ness Avenue Bus Rapid Transit Project. San Francisco County Transportation Authority. July 2013. pp. A1-1 to A1-9.

- ^ Rogozen, Nehama (Summer 2021). "Red transit lanes unique in design" (PDF). Van Ness Improvement Project Newsletter. No. 19. San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency.

- ^ a b Van Ness Avenue Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Feasibility Study (PDF) (Report). San Francisco County Transportation Authority. December 2006.

- ^ von Krogh, Bonnie Jean (April 6, 2020). "Muni Prepares to Deliver Essential Trips Only" (Press release). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency.

- ^ a b "Golden Gate Transit Guide, Winter 2021/22" (PDF). Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. December 12, 2021.

- ^ "Golden Gate Transit Bus Stop List" (PDF). Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. December 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Chapter 2: Project Alternatives". Final Environmental Impact Statement/Environmental Impact Report: Van Ness Avenue Bus Rapid Transit Project (PDF). San Francisco County Transportation Authority. July 2013. pp. 2-1 – 2-3.

- ^ "Van Ness Avenue BRT, San Francisco California" (PDF). Federal Transit Administration, United States Department of Transportation. November 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Lizzie (December 27, 2016). "Feds award millions to Van Ness Avenue bus improvement project". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Van Ness Avenue: What Lies Beneath (PDF) (Report). San Francisco Civil Grand Jury. June 2021.

- ^ "Van Ness Improvement Project". San Francisco County Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on March 30, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Transportation Secretary Buttigieg Announces $250 Million in American Rescue Plan Funding Allocations to Advance 22 Transit Projects in 13 States" (Press release). United States Federal Transit Administration. June 11, 2021.

- ^ Van Ness Avenue Bus Rapid Transit Public Art Project: Project Summary (PDF) (Report). San Francisco Arts Commission. August 21, 2013.

- ^ Pardo, Jorge (October 2015). "San Francisco Van Ness BRT Proposal" (PDF). City and County of San Francisco.

- ^ "Selected Artwork Proposal for the Van Ness Bus Rapid Transit Public Art Project" (Press release). San Francisco Arts Commission. September 9, 2015. Archived from the original on September 20, 2015.

- ^ Caltagirone, Shelley; Frye, Tim (March 8, 2017). "Van Ness BRT Public Art Installation, Case No. 2014-001204CWP" (PDF). Architectural Review Committee of the Historic Preservation Commission, San Francisco Planning Department.

- ^ "Meeting of the Full Arts Commission". San Francisco Arts Commission. October 2, 2017.

RESOLUTION NO. 1002-17-291: Motion to authorize the Director of Cultural Affairs to enter into contract with artist Jorge Pardo for an amount not to exceed $815,000 for the design development, construction documents, fabrication, transportation and consultation during installation, for the Van Ness Avenue Bus Rapid Transit Project

- ^ "Van Ness Bus Rapid Transit Public Art". San Francisco Arts Commission. Archived from the original on February 21, 2022.

- ^ "Van Ness Bus Rapid Transit: Public Art Project for Geary Boarding Platforms" (PDF). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. February 21, 2019.

- ^ Tyler, Carolyn (November 19, 2014). "Concerns raised over BRT lanes on San Francisco's Van Ness Avenue". ABC7 News. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ a b c Rodriguez, Joe Fitzgerald (January 15, 2016). "Trees, historic trolley poles to be removed for bus project". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ a b Swan, Rachel (August 18, 2019). "City says it's back on track with long-delayed Van Ness transit project". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on August 18, 2019.

- ^ Sisto, Carrie (September 25, 2020). "City offers grants to Van Ness businesses impacted by construction, but some say it's not enough". Hoodline. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (July 15, 2014). "Muni opposition hinders bus rapid transit". San Francisco Gate. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ "Xcelsior Trolley-Electric bus brochure" (PDF). New Flyer. September 8, 2021.

- ^ Saage, Lee (July 9, 2014). Major Capital Projects Update — Van Ness Avenue Bus Rapid Transit Project (PDF) (Report). San Francisco County Transportation Agency.

- ^ a b c d San Francisco Department of Public Works, Bureau of Engineering (October 2, 2009). Van Ness Avenue Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Overhead Contact System (OCS) Support Poles / Streetlights: Conceptual Engineering Report (PDF) (Report). San Francisco County Transportation Authority.

- ^ a b c d e JRP Historical Consulting (December 2009). Historic Resources Inventory and Evaluation Report, Van Ness Avenue Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Project, San Francisco California (PDF) (Report). San Francisco County Transportation Authority.

- ^ Brown, Darcy; Buhler, Mike; Warshell, Jim (September 19, 2016). "Save San Francisco's Ribbon of Light". Beyond Chron. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ a b Gabancho, Peter (December 16, 2016). "Alternative streetlight design for Van Ness Avenue" (PDF). Historic Preservation Commission.

- ^ a b Matier, Phil; Ross, Andrew (October 22, 2017). "Retro-look Van Ness streetlights back in plan, but purists take dim view". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on February 1, 2018.

- ^ "Van Ness H-line Poles Becoming History". Market Street Railway. January 15, 2016. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Perles, Anthony (1981). The People's Railway: The History of the Municipal Railway of San Francisco. Interurban Press. ISBN 0916374424.

- ^ a b c McKane, John; Perles, Anthony (1982). Inside Muni: The Properties and Operations of the Municipal Railway of San Francisco. Glendale, California: Interurban Press. pp. 174–192, 203, 225, 232, 234, 239. ISBN 0-916374-49-1.

- ^ "Department of Public Works: Projects Contemplated". Journal of Proceedings, Board of Supervisors, City and County of San Francisco. 29 (2). San Francisco Board of Supervisors: 71–73. January 8, 1934.

- ^ Beach, Cameron; Laubscher, Rick (October 5, 2020). "What might have been". Market Street Railway. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ "S.F. Stops Listed for New Marin Transit". The San Francisco Examiner. December 23, 1971. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Callwell, Robert (September 1999). "Transit in San Francisco: A Selected Chronology, 1850–1995" (PDF). San Francisco Municipal Railway. pp. 58, 67.

- ^ Mitchell, Dave (August 17, 1983). "Muni to test-drive 16 routes — 3rd big change since 1979". San Francisco Examiner. p. 14 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "SAN FRANCISCO / Revised MUNI routes beginning tomorrow". SF Gate. June 8, 2001. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ "San Francisco Voter Information Pamphlet" (PDF). San Francisco Department of Elections. November 7, 1989. p. 34. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 17, 2019. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ a b Four Corridor Plan. San Francisco County Transportation Authority. June 1995 – via Internet Archive 2018.

- ^ Rodriguez, Joe Fitzgerald (October 26, 2015). "Planning new transit '90s style". San Francisco Examiner. p. A8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "San Francisco Voter Information Pamphlet" (PDF). San Francisco Department of Elections. November 4, 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 17, 2019. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ a b c San Francisco Countywide Transportation Plan (PDF) (Report). San Francisco County Transportation Authority. July 2004.

- ^ Bialick, Aaron (December 2, 2011). "What's the Hold Up for Van Ness BRT?". Streetsblog SF. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ "Editorial: Let the buses roll in San Francisco". San Francisco Chronicle. January 21, 2007. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Parsons Transportation Group (March 2008). Van Ness Avenue Bus Rapid Transit Technical Memorandum: BRT Design Criteria (PDF) (Report). San Francisco County Transportation Authority.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael; Wildermuth, John (November 7, 2011). "Proposed Van Ness rapid bus touted for speed, reliability". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c "10: Alternatives Analysis and the Locally Preferred Option" (PDF). Final Environmental Impact Statement / Environmental Impact Report: Van Ness Avenue Bus Rapid Transit Project (Report). San Francisco County Transportation Authority. July 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Calendar Item No 10.3" (PDF). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. February 10, 2020. p. 5.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (May 7, 2014). "Why bus rapid transit has stalled in Bay Area". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Tucker, Jill (August 24, 2015). "Neighbors speak up to save Van Ness Avenue trees". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (October 30, 2015). "Transit project changes: What it means for your Bay Area commute". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Cronin, Sean (Spring 2016). "Constructing Your New Avenue" (PDF). Van Ness Improvement Project Newsletter. No. 2. San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency.

- ^ "First Step for Van Ness BRT: Consolidating Bus Stops to Save Travel Time" (Press release). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. May 20, 2016.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (October 4, 2016). "Upgrades to Van Ness, Polk streets will require patience". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (November 14, 2016). "Left turns whittled down on SF's Van Ness Avenue". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ "You Asked!" (PDF). Van Ness Improvement Project. No. 5. San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Spring 2017. p. 2.

- ^ Chinn, Jerold (March 2, 2017). "Work begins on Van Ness transit corridor". SF Bay. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ Rodriguez, Joe Fitzgerald (October 16, 2017). "Two-mile-long Van Ness bus lane project faces two-year delay". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ Rodriguez, Joe Fitzgerald (April 23, 2018). "Van Ness Bus Rapid Transit construction delayed another 5 months". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ Morales-Zanoletti, Estefani (Spring 2019). "Digging up history under Van Ness" (PDF). Van Ness Improvement Project Newsletter. No. 10. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Daniels, Meghan (Summer 2018). "Hidden City: Utilities Under Van Ness" (PDF). Van Ness Improvement Project Newsletter. No. 7. San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency.

- ^ "Project Timeline" (PDF). Van Ness Improvement Project Newsletter. No. 9. San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Winter 2019.

- ^ Morales-Zanoletti, Estefani (Summer 2019). "Traffic Switch on Van Ness Avenue" (PDF). Van Ness Improvement Project Newsletter. No. 11. San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency.

- ^ Rogozen, Nehama (Summer 2020). "Building the BRT: Construction moves to the center" (PDF). Van Ness Improvement Project Newsletter. No. 15. San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency.

- ^ "Traffic switches on Van Ness" (PDF). Van Ness Improvement Project Newsletter. No. 16. San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Fall 2020.

- ^ "Uncovering Cal Cable's past". Market Street Railway. October 24, 2020. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ "Original tracks from California Street cable car line uncovered on Van Ness" (PDF). Van Ness Improvement Project Newsletter. No. 17. San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Winter 2021.

- ^ Graf, Carly (December 3, 2020). "SFMTA board scrutinizes Van Ness BRT spending". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Barmann, Jay (November 10, 2020). "Four Years Into Van Ness Bus Lane Project, Red Concrete Gets Poured for Lanes". SFist. Archived from the original on February 21, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Jeffrey Tumlin 🏳️🌈 [@jeffreytumlin] (November 10, 2020). "Crews are hard at work today putting down red concrete for Van Ness Ave bus lanes" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "Trees bring life to Van Ness corridor" (PDF). Van Ness Improvement Project Newsletter. No. 18. San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Spring 2021.

- ^ Jeffrey Tumlin 🏳️🌈 [@jeffreytumlin] (June 30, 2021). "I spend most days pouring over spreadsheets, editing docs + sitting thru 8 hrs of Zoom meetings. So I leapt at chance to join Bauman crews pouring final blocks of Van Ness red lanes. That's me⬇️" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Cano, Ricardo (July 2, 2021). "Van Ness project has been plagued by delays and ruined businesses. Grand jury says setbacks were 'avoidable'". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on February 15, 2022.

- ^ Cordoba, Eric (September 17, 2021). "09/22/2021 Community Advisory Committee Meeting: Progress Report for Van Ness Avenue Bus Rapid Transit Project" (PDF). San Francisco County Transportation Authority.

The project has now completed construction of the center-running red transit lanes, a significant milestone.

- ^ SFMTA [@sfmta_muni] (January 12, 2022). "Today, along with @GoldenGateBus , we began joint testing of #VanNessBRT. We're making sure that signals work as well as addressing turn and passing clearances with vehicles traveling in the opposite direction" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Rogozen, Nehama (January 25, 2022). "Bus Testing on the New Van Ness BRT Corridor a Success" (Press release). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency.

- ^ Stinson, Sarah (April 1, 2022). "New Van Ness rapid transit unveils today". KRON4. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ Cano, Ricardo (April 28, 2022). "One month after its debut, this is how S.F.'s Van Ness BRT is performing". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- ^ "Trolleynews [regular news section]". Trolleybus Magazine. Vol. 58, no. 363. UK: National Trolleybus Association. May–June 2022. pp. 128–129. ISSN 0266-7452.

- ^ "Trolleynews [regular news section]". Trolleybus Magazine. Vol. 58, no. 365. UK: National Trolleybus Association. September–October 2022. p. 217. ISSN 0266-7452.

- ^ "Trolleynews [regular news section]". Trolleybus Magazine. Vol. 59, no. 367. UK: National Trolleybus Association. January–February 2023. p. 41. ISSN 0266-7452.

- ^ Gravener, John (September 3, 2024). "International Review of Van Ness BRT Ranks it Among Top in the World" (Press release). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency.

External links

- SFMTA project website

- SFCTA project website

- Final Environmental Impact Statement: Volume I, Volume II, Addendum (2016)