Upper Canada

Province of Upper Canada | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1791–1841 | |||||||||

| Anthem: "God Save the King/Queen" | |||||||||

Map of Upper Canada (orange) with 21st-century Canada (pink) surrounding it | |||||||||

| Status | British colony | ||||||||

| Capital | Newark 1792–1797 (renamed Niagara 1798, Niagara-on-the-Lake 1970) York (later renamed Toronto in 1834) 1797–1841 | ||||||||

| Common languages | English | ||||||||

| Religion | Church of England (Official) [3] | ||||||||

| Government | Family Compact | ||||||||

| Sovereign | |||||||||

• 1791–1820 | George III | ||||||||

• 1820–1830 | George IV | ||||||||

• 1830–1837 | William IV | ||||||||

• 1837–1841 | Victoria | ||||||||

| Lieutenant-Governor; Executive Council of Upper Canada | |||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament of Upper Canada | ||||||||

| Legislative Council | |||||||||

| Legislative Assembly | |||||||||

| Historical era | British Era | ||||||||

| 26 December 1791 | |||||||||

| 10 February 1841 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1836[4] | 258,999 km2 (100,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1823[4] | 150,196 | ||||||||

• 1836[4] | 358,187 | ||||||||

| Currency | Halifax pound | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

| History of Ontario | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Upper Canada Topics | ||||||||||||

| Province of Canada Topics | ||||||||||||

| Province of Ontario topics | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

The Province of Upper Canada (French: province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the Province of Quebec since 1763. Upper Canada included all of modern-day Southern Ontario and all those areas of Northern Ontario in the Pays d'en Haut which had formed part of New France, essentially the watersheds of the Ottawa River or Lakes Huron and Superior, excluding any lands within the watershed of Hudson Bay. The "upper" prefix in the name reflects its geographic position along the Great Lakes, mostly above the headwaters of the Saint Lawrence River, contrasted with Lower Canada (present-day Quebec) to the northeast.

Upper Canada was the primary destination of Loyalist refugees and settlers from the United States after the American Revolution, who often were granted land to settle in Upper Canada. Already populated by Indigenous peoples, land for settlement in Upper Canada was made by treaties between the new British government and the Indigenous peoples, exchanging land for one-time payments or annuities. The new province was characterized by its British way of life, including bicameral parliament and separate civil and criminal law, rather than mixed as in Lower Canada or elsewhere in the British Empire.[5][failed verification] The division was created to ensure the exercise of the same rights and privileges enjoyed by loyal subjects elsewhere in the North American colonies.[6] In 1812, war broke out between Great Britain and the United States, leading to several battles in Upper Canada. The United States attempted to capture Upper Canada, but the war ended with the situation unchanged.

The government of the colony came to be dominated by a small group of persons, known as the "Family Compact", who held most of the top positions in the Legislative Council and appointed officials. In 1837, an unsuccessful rebellion attempted to overthrow the undemocratic system. Representative government would be established in the 1840s. Upper Canada existed from its establishment on 26 December 1791 to 10 February 1841, when it was united with adjacent Lower Canada to form the Province of Canada.

Establishment

As part of the 1763 Treaty of Paris which ended the Seven Years' War global conflict and the French and Indian War in North America, Great Britain retained control over the former New France, which had been defeated in the French and Indian War. The British had won control after Fort Niagara had surrendered in 1759 and Montreal capitulated in 1760, and the British under Robert Rogers took formal control of the Great Lakes region in 1760.[7] Fort Michilimackinac was occupied by Roger's forces in 1761.

The territories of contemporary southern Ontario and southern Quebec were initially maintained as the single province of Quebec, as it had been under the French. From 1763 to 1791, the Province of Quebec maintained its French language, cultural behavioural expectations, practices and laws. The British passed the Quebec Act in 1774, which expanded the Quebec colony's authority to include part of the Indian Reserve to the west (i.e., parts of southern Ontario), and other western territories south of the Great Lakes including much of what would become the United States' Northwest Territory, including the modern states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin and parts of Minnesota.

After the American War of Independence ended in 1783, Britain retained control of the area north of the Ohio River. The official boundaries remained undefined until 1795 and the Jay Treaty. The British authorities encouraged the movement of people to this area from the United States, offering free land to encourage population growth. For settlers, the head of the family received 100 acres (40 ha) and 50 acres (20 ha) per family member, and soldiers received larger grants.[8] These settlers are known as United Empire Loyalists and were primarily English-speaking Protestants. The first townships (Royal and Cataraqui) along the St. Lawrence and eastern Lake Ontario were laid out in 1784, populated mainly with decommissioned soldiers and their families.[9]

"Upper Canada" became a political entity on 26 December 1791 with the Parliament of Great Britain's passage of the Constitutional Act of 1791. The act divided the province of Quebec into Upper and Lower Canada, but did not yet specify official borders for Upper Canada. The division was effected so that Loyalist American settlers and British immigrants in Upper Canada could have English laws and institutions, and the French-speaking population of Lower Canada could maintain French civil law and the Catholic religion. The first lieutenant-governor was John Graves Simcoe.[10]

The 1795 Jay Treaty officially set the borders between British North America and the United States north to the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River. On 1 February 1796, the capital of Upper Canada was moved from Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake) to York (now Toronto), which was judged to be less vulnerable to attack by the US.

The Act of Union 1840, passed 23 July 1840 by the British Parliament and proclaimed by the Crown on 10 February 1841, merged Upper Canada with Lower Canada to form the short-lived United Province of Canada.

Government

Provincial administration

Upper Canada's constitution was said to be "the very image and transcript" of the British constitution, and based on the principle of "mixed monarchy" – a balance of monarchy, aristocracy and democracy.[11]

The Executive arm of government in the colony consisted of a lieutenant-governor, his executive council, and the Officers of the Crown (equivalent to the Officers of the Parliament of Canada): the Adjutant General of the Militia, the Attorney General, the Auditor General of Land Patents for Upper Canada, the Auditor General (only one appointment ever made), Crown Lands Office, Indian Office, Inspector General, Kings' Printer, Provincial Secretary and Registrar's Office, Receiver General of Upper Canada, Solicitor General, and Surveyor General.[12]

The Executive Council of Upper Canada had a similar function to the Cabinet in England but was not responsible to the Legislative Assembly. They held a consultative position, however, and did not serve in administrative offices as cabinet ministers do. Members of the Executive Council were not necessarily members of the Legislative Assembly but were usually members of the Legislative Council.[13]

Parliament

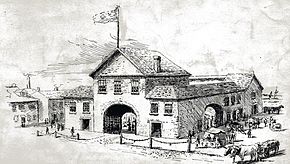

The Legislative branch of the government consisted of the parliament comprising legislative council and legislative assembly. When the capital was first moved to Toronto (then called York) from Newark (present-day Niagara-on-the-Lake) in 1796, the Parliament Buildings of Upper Canada were at the corner of Parliament and Front Streets, in buildings that were burned by US forces in the War of 1812, rebuilt, then burned again by accident in 1824. The site was eventually abandoned for another, to the west.

The Legislative Council of Upper Canada was the upper house governing the province of Upper Canada. Although modelled after the British House of Lords, Upper Canada had no aristocracy. Members of the Legislative council, appointed for life, formed the core of the oligarchic group, the Family Compact, that came to dominate government and economy in the province.

The Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada functioned as the lower house in the Parliament of Upper Canada. Its legislative power was subject to veto by the appointed Lieutenant Governor, Executive Council, and Legislative Council.

Districts and Local Government

Local government in the province of Upper Canada was based on districts. Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester created four districts 24 July 1788.[14]

- Lunenburgh District, later "Eastern"

- Mecklenburg District, later "Midland"

- Nassau District, later "Home"

- Hesse District, later "Western"

For militia and parliamentary purposes, Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe in a proclamation 16 July 1792 divided these districts into the nineteen original counties of Ontario: Glengarry, Stormont, Dundas, Grenville, Leeds, Frontenac, Ontario, Addington, Lennox, Prince Edward, Hastings, Northumberland, Durham, York, Lincoln, Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex and Kent.

By 1800, the four districts of Eastern, Midland, Home and Western had been increased to eight, the new ones being Johnston, Niagara, London and Newcastle. Additional districts were created from the existing districts as the population grew until 1849, when local government mainly based on counties came into effect. At that time, there were 20 districts; legislation to create a new Kent District was never completed. Up until 1841, the district officials were appointed by the lieutenant-governor, although usually with local input.

Justices of the Peace were appointed by the Lt. Governor. Any two justices meeting together could form the lowest level of the justice system, the Courts of Request. A Court of Quarter Sessions was held four times a year in each district composed of all the resident justices. The Quarter Sessions met to oversee the administration of the district and deal with legal cases. They formed, in effect, the municipal government until an area was incorporated as either a Police Board or a City after 1834.[15]

List of cities and towns of Upper Canada

Incorporated in Upper Canada era (to 1841)

- York (now Toronto), capital of Upper Canada

- Kingston

- Brockville

- Hamilton

- Cornwall

- Prescott

- Port Hope

- Picton

- Cobourg

- London

Incorporated in Canada West (1841-1867)

- Newark, now Niagara-on-the-Lake

- Brantford

- Bytown (now Ottawa)

- Goderich

- Belleville

- Peterborough

- Perth

- Napanee

- Guelph

- Whitby

- Paris, Ontario

- Lindsay, now part of Kawartha Lakes

- Galt, now part of Cambridge, Ontario

- Welland

- Sandwich (now Windsor)

- Stratford, Ontario

Politics

Family Compact

The Family Compact is the epithet applied to an oligarchic group of men who exercised most of the political and judicial power in Upper Canada from the 1810s to the 1840s. It was noted for its conservatism and opposition to democracy.[16] The uniting factors amongst the Compact were its loyalist tradition, hierarchical class structure and adherence to the established Anglican Church. Leaders such as John Beverley Robinson and John Strachan proclaimed it an ideal government, especially as contrasted with the rowdy democracy in the nearby United States.[17] The Family Compact emerged from the War of 1812 and collapsed in the aftermath of the Rebellions of 1837.

- Bishop Strachan, the acknowledged Anglican leader of the Family Compact

- John Robinson, acknowledged leader of the Family Compact, member of the Legislative Assembly and later the Legislative Council[18]

- William Henry Boulton, 8th Mayor of Toronto and member of the Legislative Assembly[19]

- Sir Allan Napier MacNab, 1st Baronet of the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada

- Henry Sherwood, 13th Parliament of Upper Canada representing Brockville

Reform movement

There were many outstanding individual reform politicians in Upper Canada, including Robert Randal, Peter Perry, Marshall Spring Bidwell, William Ketchum and Dr. William Warren Baldwin; however, organised collective reform activity began with Robert Fleming Gourlay. Gourlay was a well-connected Scottish emigrant who arrived in 1817, hoping to encourage "assisted emigration" of the poor from Britain. He solicited information on the colony through township questionnaires, and soon became a critic of government mismanagement. When the local legislature ignored his call for an inquiry, he called for a petition to the British Parliament. He organised township meetings, and a provincial convention – which the government considered dangerous and seditious. Gourlay was tried in December 1818 under the 1804 Sedition Act and jailed for 8 months. He was banished from the province in August 1819. His expulsion made him a martyr in the reform community.[20]

The next wave of organised Reform activity emerged in the 1830s through the work of William Lyon Mackenzie, James Lesslie, John Rolph, William John O'Grady and Dr Thomas Morrison, all of Toronto. They were critical to introducing the British Political Unions to Upper Canada. Political Unions were not parties. The unions organised petitions to Parliament.

The Upper Canada Central Political Union was organised in 1832–33 by Dr Thomas David Morrison (mayor of Toronto in 1836) while William Lyon Mackenzie was in England. This union collected 19,930 signatures on a petition protesting Mackenzie's unjust expulsion from the House of Assembly by the Family Compact.[21]

This union was reorganised as the Canadian Alliance Society (1835). It shared a large meeting space in the market buildings with the Mechanics Institute and the Children of Peace. The Canadian Alliance Society adopted much of the platform (such as secret ballot & universal suffrage) of the Owenite National Union of the Working Classes in London, England, that were to be integrated into the Chartist movement in England.[22]

The Canadian Alliance Society was reborn as the Constitutional Reform Society (1836), when it was led by the more moderate reformer, Dr William W. Baldwin. After the disastrous 1836 elections, it took the final form as the Toronto Political Union in 1837. It was the Toronto Political Union that called for a Constitutional Convention in July 1837, and began organising local "Vigilance Committees" to elect delegates. This became the organizational structure for the Rebellion of 1837.[23]

Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837

The Upper Canada Rebellion was an insurrection against the oligarchic government of the Family Compact in December 1837, led by William Lyon Mackenzie. Long term grievances included antagonism between Later Loyalists and British Loyalists, political corruption, the collapse of the international financial system and the resultant economic distress, and a growing republican sentiment. While public grievances had existed for years, it was the Lower Canada Rebellion (in present-day Quebec) that emboldened rebels in Upper Canada to revolt openly soon after. The Upper Canada Rebellion was largely defeated shortly after it began, although resistance lingered until 1838 (and became more violent) – mainly through the support of the Hunters' Lodges, a secret anti-British American militia that emerged in states around the Great Lakes. They launched the Patriot War in 1838–39.[24]

John Lambton, Lord Durham's support for "responsible government" undercut the Tories and gradually led the public to reject what it viewed as poor administration, unfair land and education policies, and inadequate attention to urgent transportation needs. Durham's report led to the administrative unification of Upper and Lower Canada as the Province of Canada in 1841. Responsible government did not occur until the late 1840s under Robert Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine.[25]

Sydenham and the Union of the Canadas

After the Rebellions, the new governor, Charles Poulett Thomson, 1st Baron Sydenham, proved an exemplary Utilitarian, despite his aristocratic pretensions. This combination of free trade and aristocratic pretensions needs to be underscored; although a liberal capitalist, Sydenham was no radical democrat. Sydenham approached the task of implementing those aspects of Durham's report that the colonial office approved of, municipal reform, and the union of the Canadas, with a "campaign of state violence and coercive institutional innovation ... empowered not just by the British state but also by his Benthamite certainties."[26] Like governors Bond Head before him, and Metcalfe after, he was to turn to the Orange Order for often violent support. It was Sydenham who played a critical role in transforming Compact Tories into Conservatives.

Sydenham introduced a vast expansion of the state apparatus through the introduction of municipal government. Areas not already governed through civic corporations or police boards would be governed through centrally controlled District Councils with authority over roads, schools, and local policing. A strengthened Executive Council would further usurp much of the elected assembly's legislative role, leaving elected politicians to simply review the administration's legislative program and budgets.

Settlement

First Nations dispossession and reserves

The First Nations occupying the territory that was to become Upper Canada were:

- Anishinaabe or Anishinabe—or more properly (plural) Anishinaabeg or Anishinabek. The plural form of the word is the autonym often used by the Odawa, Ojibwe, and Algonquin peoples.

- The Iroquois, also known as the Haudenosaunee or the "People of the Longhouse",[27]

Prior to the creation of Upper Canada in 1791, much land had already been ceded by the First Nations to the Crown in accordance with the Royal Proclamation of 1763. The first treaty was between the Seneca and the British in 1764, giving access to lands adjoining the Niagara River.[28] During the American Revolutionary War most of the First Nations supported the British. After the Americans launched a campaign that burned the villages of the Iroquois in New York State in 1779[29] the refugees fled to Fort Niagara and other British posts, and remained permanently in Canada.

Land was granted to these allied Six Nations who had served on the British side during the American Revolution by the Haldimand Proclamation (1784). Haldimand had purchased a tract of land from the Mississaugas. The nature of the grant and the administration of land sales by Upper Canada and Canada is a matter of dispute.

Between 1783 and 1812, fifteen land surrender treaties were concluded in Upper Canada. These involved one-time payments of money or goods to the Indigenous peoples. Some of the treaties spelled out designated reserve lands for the Indigenous peoples.[30]

Following the War of 1812, European settlers came in increasing numbers. The Indian Department focussed on converting the Indigenous peoples to abandon their old way of life and adopt agriculture. The treaties shifted from one-time payments in exchange to annual annuities from the sale of surrendered lands. Between 1825 and 1860, treaties were concluded for nearly all of the land-mass of the future province of Ontario. In 1836, Manitoulin Island was designated as a reserve for dispossessed natives, but much of this was ceded in 1862.[30]

Loyalists and the land grant system

Crown land policy to 1825 was multi-fold in the use of a "free" resource that had value to people who themselves may have little or no money for its purchase and for the price of settling upon it to support themselves and a create a new society. First, the cash-strapped Crown government in Canada could pay and reward the services and loyalty of the "United Empire Loyalists" who, originated outside of Canada, without encumbrance of debt by being awarded with small portions of land (under 200 acres or 80 hectares) with the proviso that it be settled by those to which it was granted; Second, portions would be reserved for the future use of the Crown and the clergy that did not require settlement by which to gain control. Lt. Governor Simcoe saw this as the mechanism by which an aristocracy might be created,[31] and that compact settlement could be avoided with the grants of large tracts of land to those Loyalists not required to settle on it as the means of gaining control.

Assisted immigration

The Calton weavers were a community of handweavers established in the community of Calton, then in Lanarkshire just outside Glasgow, Scotland in the 18th century.[32] In the early 19th century, many of the weavers emigrated to Canada, settling in Carleton Place and other communities in eastern Ontario, where they continued their trade.[33]

In 1825, 1,878 Irish Immigrants from the city of Cork arrived in the community of Scott's Plains. The British Parliament had approved an experimental emigration plan to transport poor Irish families to Upper Canada in 1822. The scheme was managed by Peter Robinson, a member of the Family Compact and brother of the Attorney General. Scott's Plains was renamed Peterborough in his honour.

Talbot settlement

Thomas Talbot emigrated in 1791, where he became personal secretary to John Graves Simcoe, Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada. Talbot convinced the government to allow him to implement a land settlement scheme of 5,000 acres (2,000 ha) in Elgin County in the townships of Dunwich and Aldborough in 1803.[34] According to his government agreement, he was entitled to 200 acres (80 ha) for every settler who received 50 acres (20 ha); in this way he gained an estate of 20,000 acres (8,000 ha). Talbot's administration was regarded as despotic. He was infamous for registering settlers' names on the local settlement map in pencil and if displeased, erasing their entry. Talbot's abuse of power was a contributing factor in the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837.[35]

Crown and clergy reserves

The Crown reserves, one seventh of all lands granted, were to provide the provincial executive with an independent source of revenue not under the control of the elected Assembly. The clergy reserves, also one seventh of all lands granted in the province, were created "for the support and maintenance of a Protestant clergy" in lieu of tithes. The revenue from the lease of these lands was claimed by the Rev. John Strachan on behalf of the Church of England. These reserves were directly administered by the Crown; which, in turn, came under increasing political pressure from other Protestant bodies. The Reserve lands were to be a focal point of dissent within the Legislative Assembly.[36]

The Clergy Corporation was incorporated in 1819 to manage the clergy reserves. After the Rev. John Strachan was appointed to the Executive Council, the advisory body to the Lieutenant Governor, in 1815, he began to push for the Church of England's autonomous control of the clergy reserves on the model of the Clergy Corporation created in Lower Canada in 1817. Although all clergymen in the Church of England were members of the body corporate, the act prepared in 1819 by Strachan's former student, Attorney General John Beverly Robinson, also appointed the Inspector General and the Surveyor General to the board, and made a quorum of three for meetings; these two public officers also sat on the Legislative Council with Strachan. These three were usually members of the Family Compact.[37]

The clergy reserves were not the only types of landed endowment for the Anglican Church and clergy. The 1791 Act also provided for glebe land to be assigned and vested in the Crown (for which 22,345 acres (9,043 ha) were set aside), where the revenues would be remitted to the Church.[38] The act also provided for the creation of parish rectories, giving parishes a corporate identity so that they could hold property (although none were created until 1836, prior to the recall of John Colborne, in which he created 24 of them).[38] They were granted lands amounting to 21,638 acres (8,757 ha), of which 15,048 acres (6,090 ha) were drawn from the clergy reserves and other glebe lots, while 6,950 acres (2,810 ha) were taken from ordinary Crown lands.[39] A later suit to have this action annulled was dismissed by the Court of Chancery of Upper Canada.[40] The Province of Canada would later pass an Act in 1866 to authorize the disposal of such glebe and rectory lands not specifically used as churches, parsonages or burial grounds.[41]

Common school lands

In 1797, lands in twelve townships (six east of York, and six west, totalling about 500,000 acres (200,000 ha), were set aside, from which revenues arising from their sale or lease were dedicated to support the establishment of grammar schools and a university for the Province.[42] They were distributed as follows:

| District | Township | Original Royal grant (1797) | Townships set aside as substituted lands[a 1] | Lands alienated | Reinvested in the Crown[a 2] | Lands disposable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To individuals | Surveyor's % | To Upper Canada College | University[a 3] | UCC | |||||

| Ottawa | Alfred | 25,140 | – | 25,140 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Plantagenet | 40,000 | – | 40,000 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Midland | Bedford | 61,220 | – | 2,678 | 2,858 | – | – | – | 55,684 |

| Hinchinbroke | 51,100 | – | – | 2,437 | – | 48,663 | – | – | |

| Sheffield | 56,688 | – | – | 3,158 | – | – | – | 53,530 | |

| Newcastle | Seymour | 47,484 | – | – | 3,515 | 25,000 | – | 18,969 | – |

| London | Blandford | 20,400 | – | – | 1,179 | 5,000 | – | – | 14,221 |

| Houghton | 19,000 | – | 1,592 | 1,505 | – | – | – | 15,893 | |

| Middleton | 35,000 | – | 22,600 | 1,667 | – | – | – | 10,733 | |

| Southwold | 40,500 | – | 30,900 | 719 | – | – | – | 8,881 | |

| Warwick | – | 600 | – | – | – | – | – | 600 | |

| Westminster | 51,143 | – | 40,725 | 1,218 | – | – | – | 9,200 | |

| Yarmouth | 20,000 | – | 7,084 | 1,026 | – | – | – | 11,900 | |

| Home | Java[a 4] | – | 12,000 | – | – | 12,000 | – | – | – |

| Luther | – | 66,000 | – | – | – | 66,000 | – | – | |

| Merlin[a 4] | – | 40,000 | – | – | – | 23,281 | 5,031 | 11,688 | |

| Osprey | – | 50,000 | – | – | – | 50,000 | – | – | |

| Proton | – | 66,000 | – | – | – | – | – | 66,000 | |

| Sunnidale | – | 38,000 | – | – | – | 38,000 | – | – | |

| Totals | 467,675 | 272,600 | 170,719 | 19,282 | 42,000 | 225,944 | 24,000 | 258,330 | |

Land sale system

The land grant policy changed after 1825 as the Upper Canadian administration faced a financial crisis that would otherwise require raising local taxes, thereby making it more dependent on a local elected legislature. The Upper Canadian state ended its policy of granting land to "unofficial" settlers and implemented a broad plan of revenue-generating sales. The Crown replaced its old policy of land grants to ordinary settlers in newly opened districts with land sales by auction. It also passed legislation that allowed the auctioning of previously granted land for payment of back-taxes.[44]

Canada Company

The greater portion of British emigrants, arriving in Canada without funds and the most exalted ideas of the value and productiveness of land, purchase extensively on credit... Everything goes on well for a short time. A log-house is erected with the assistance of old settlers, and the clearing of forest is commenced. Credit is obtained at a neighbouring store ... During this period he has led a life of toil and privation... On the arrival of the fourth harvest, he is reminded by the storekeeper to pay his account with cash, or discharge part of it with his disposable produce, for which he gets a very small price. He is also informed that the purchase money of the land has been accumulating with interest ... he finds himself poorer than when he commenced operation. Disappointment preys on his spirit... the land ultimately reverts to the former proprietor, or a new purchaser is found.

— Patrick Shirreff, 1835

Few chose to lease the Crown reserves as long as free grants of land were still available. The Lieutenant Governor increasingly found himself depending upon the customs duties shared with, but collected in Lower Canada for revenue; after a dispute with the lower province on the relative proportions to be allocated to each, these duties were withheld, forcing the Lieutenant Governor to search for new sources of revenue. The Canada Company was created as a means of generating government revenue that was not under the control of the elected Assembly, thereby granting the Lt. Governor greater independence from local voters.

The plan for the Canada Company was promoted by the province's Attorney General, John Beverly Robinson, then studying law at Lincoln's Inn in London. The Lt. Governor's financial crisis led to a quick adoption of Robinson's scheme to sell the Crown reserves to a new land company which would provide the provincial government with annual payments of between £15,000 to £20,000. The Canada Company was chartered in London in 1826; after three years of mismanagement by John Galt, the company hired William Allan and Thomas Mercer Jones to manage the company's Upper Canadian business. Jones was to manage the "Huron Tract," and Allan to sell the Crown reserves already surveyed in other districts.[45]

According to the Canada Company, "the poorest individual can here procure for himself and family a valuable tract; which, with a little labour, he can soon convert into a comfortable home, such as he could probably never attain in any other country – all his own!" However, recent studies have suggested that a minimum of £100 to £200 plus the cost of land was required to start a new farm in the bush. As a result, few of these poor settlers had any hope of starting their own farm, although many tried.[46]

Huron Tract

The Huron Tract lies in the counties of Huron, Perth, Middlesex and present-day Lambton County, Ontario, bordering on Lake Huron to the west and Lake Erie to the east. The tract was purchased by the Canada Company for resale to settlers. Influenced by William "Tiger" Dunlop, John Galt and other businessmen formed the Canada Company.[47] The Canada Company was the administrative agent for the Huron Tract.

Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1806 | 70,718 | — |

| 1811 | 76,000 | +7.5% |

| 1814 | 95,000 | +25.0% |

| 1824 | 150,066 | +58.0% |

| 1825 | 157,923 | +5.2% |

| 1826 | 166,379 | +5.4% |

| 1827 | 177,174 | +6.5% |

| 1828 | 186,488 | +5.3% |

| 1829 | 197,815 | +6.1% |

| 1830 | 213,156 | +7.8% |

| 1831 | 236,702 | +11.0% |

| 1832 | 263,554 | +11.3% |

| 1833 | 295,863 | +12.3% |

| 1834 | 321,145 | +8.5% |

| 1835 | 347,359 | +8.2% |

| 1836 | 374,099 | +7.7% |

| 1837 | 397,489 | +6.3% |

| 1838 | 399,422 | +0.5% |

| 1839 | 409,048 | +2.4% |

| 1840 | 432,159 | +5.6% |

| Source: Statistics Canada website Censuses of Canada 1665 to 1871. See United Province of Canada for population after 1840. | ||

Ethnic groups

Although the province is frequently referred to as "English Canada" after the Union of the Canadas,[by whom?] and its ethnic homogeneity said to be a factor in the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837,[by whom?] there was range of ethnic groups in Upper Canada. However, due to the lack of a detailed breakdown, it is difficult to count each group, and this may be considered abuse of statistics. An idea of the ethnic breakdown can be had if one considers the religious census of 1842, which is helpfully provided below: Roman Catholics were 15% of the population, and adherents to this religion were, at the time, mainly drawn from the Irish and the French settlers. The Roman Catholic faith also numbered some votaries from amongst the Scottish settlers. The category of "other" religious adherents, somewhat under 5% of the population, included the Aboriginal and Metis culture.

First Nations

See above: Land Settlement

- Anishinaabe or Anishinabe—or more properly (plural) Anishinaabeg or Anishinabek. The plural form of the word is the autonym often used by the Odawa, Ojibwe, and Algonquin peoples.

- The Haudenosaunee, also known as the Iroquois or the "People of the Longhouse",[27]

Métis

Many British and French-Canadian fur traders married First Nations women from the Cree, Ojibwa, or Saulteaux First Nations. The majority of these fur traders were Scottish and French and were Catholic.[48]

Canadiens/French-Canadians

Early settlements in the region include the Mission of Sainte-Marie among the Hurons at Midland in 1649, Sault Ste. Marie in 1668, and Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit in 1701. Southern Ontario was part of the Pays d'en-haut (Upper Country) of New France, and later part of the province of Quebec until Quebec was split into Upper and Lower Canada in 1791. The first wave of settlement in the Detroit/Windsor area came in the 18th century during the French regime. A second wave came in the 19th and early 20th centuries to the areas of Eastern Ontario and Northeastern Ontario. In the Ottawa Valley, in particular, some families have moved back and forth across the Ottawa River for generations (the river is the border between Ontario and Quebec). In the city of Ottawa some areas such as Vanier and Orleans have a rich Franco-heritage where families often have members on both sides of the Ottawa River.

Loyalists/Later Loyalists

After an initial group of about 7,000 United Empire Loyalists were thinly settled across the province in the mid-1780s, a far larger number of "late-Loyalists" arrived in the late 1790s and were required to take an oath of allegiance to the Crown to obtain land if they came from the US. Their fundamental political allegiances were always considered dubious. By 1812, this had become acutely problematic since the American settlers outnumbered the original Loyalists by more than ten to one. Following the War of 1812, the colonial government under Lt. Governor Gore took active steps to prevent Americans from swearing allegiance, thereby making them ineligible to obtain land grants. The tensions between the Loyalists and late Loyalists erupted in the "Alien Question" crisis in 1820–21 when the Bidwells (Barnabas and his son Marshall) sought election to the provincial assembly. They faced opponents who claimed they could not hold elective office because of their American citizenship. If the Bidwells were aliens so were the majority of the province. The issue was not resolved until 1828 when the Colonial government retroactively granted them citizenship.

Freed slaves

The Act Against Slavery passed in Upper Canada on 9 July 1793. The 1793 "Act against Slavery" forbade the importation of any additional slaves and freed children. It did not grant freedom to adult slaves—they were finally freed by the British Parliament in 1833. As a consequence, many Canadian slaves fled south to New England and New York, where slavery was no longer legal. Many American slaves who had escaped from the South via the Underground Railroad or fleeing from the Black Codes in the Ohio Valley came north to Ontario, a good portion settling on land lots and began farming.[49] It is estimated that thousands of escaped slaves entered Upper Canada from the United States.[50]

British

The Great Migration from Britain from 1815 to 1850 has been numbered at 800,000. The population of Upper Canada in 1837 is documented at 409,000. Given the lack of detailed census data, it is difficult to assess the relative size of the American and Canadian born "British" and the foreign-born "British." By the time of the first census in 1841, only half of the population of Upper Canada were foreign-born British.[51]

Irish

Scottish

English

Religion

| Year | Pop. |

|---|---|

| Baptists | 16,411 |

| Catholics | 65,203 |

| Anglican | 107,791 |

| Congregational | 4,253 |

| Jews | 1,105 |

| Lutherans | 4,524 |

| Methodists | 82,923 |

| Moravians | 1,778 |

| Presbyterians | 97,095 |

| Quakers | 5,200 |

| Others | 19,422 |

| Source: Statistics Canada website Censuses of Canada 1665 to 1871. See United Province of Canada for population after 1840. | |

Church of England

The first Lt. Governor, Sir John Graves Simcoe, sought to make the Church of England the Established Church of the province. To that end, he created the clergy reserves, the revenues of which were to support the church. The clergy reserves proved to be a long-term political issue, as other denominations, particularly the Church of Scotland (Presbyterians) sought a proportional share of the revenues. The Church of England was never numerically dominant in the province, as it was in England, especially in the early years when most of the American born Later Loyalists arrived. The growth of the Church of England depended largely on later British emigration for growth.

The Church was led by the Rev. John Strachan (1778–1867), a pillar of the Family Compact. Strachan was part of the oligarchic ruling class of the province, and besides leading the Church of England, also sat on the Executive Council, the Legislative Council, helped found the Bank of Upper Canada, Upper Canada College, and the University of Toronto.

Catholic Church

Father Alexander Macdonell was a Scottish Catholic priest who formed his evicted clan into The Glengarry Fencibles regiment, of which he was chaplain. He was the first Catholic chaplain in the British Army since the Reformation. When the regiment was disbanded, Rev. Macdonell appealed to the government to grant its members a tract of land in Canada, and, in 1804, 160,000 acres (60,000 ha) were provided in what is now Glengarry County, Canada. In 1815, he began his service as the first Roman Catholic Bishop at St. Raphael's Church in the Highlands of Ontario.[52] In 1819, he was appointed Vicar Apostolic of Upper Canada, which in 1826 was erected into a suffragan bishopric of the Archdiocese of Quebec.[53][54] In 1826, he was appointed to the legislative council.[55]

Macdonell's role on the Legislative Council was one of the tensions with the Toronto congregation, led by Father William O'Grady. O'Grady, like Macdonell, had been an army chaplain (to Connell James Baldwin's soldiers in Brazil). O'Grady followed Baldwin to Toronto Gore Township in 1828. From January 1829 he was pastor of St. Paul's church in York. Tensions between the Scottish and Irish came to a head when O'Grady was defrocked, in part for his activities in the Reform movement. He went on to edit a Reform newspaper in Toronto, the Canadian Correspondent.

Ryerson and the Methodists

The undisputed leader of the highly fractious Methodists in Upper Canada was Egerton Ryerson, editor of their newspaper, The Christian Guardian. Ryerson (1803–1882) was an itinerant minister – or circuit rider – in the Niagara area for the Methodist Episcopal Church – an American branch of Methodism. As British immigration increased, Methodism in Upper Canada was torn between those with ties to the Methodist Episcopal Church and the British Wesleyan Methodists. Ryerson used the Christian Guardian to argue for the rights of Methodists in the province and, later, to help convince rank-and-file Methodists that a merger with British Wesleyans (effected in 1833) was in their best interest.

Presbyterians

The earliest Presbyterian ministers in Upper Canada came from various denominations based in Scotland, Ireland, and the United States. The "Presbytery of the Canadas" was formed in 1818 primarily by Scottish Associate Presbyterian missionaries, yet independently of their mother denomination in the hope of including Presbyterian ministers of all stripes in Upper and Lower Canada. Although successfully including members from Irish Associate, and American Presbyterian and Reformed denominations, the growing group of missionaries belonging to the Church of Scotland remained separate. Instead, in 1831, they formed their own "Synod of the Presbyterian Church of Canada in Connection with the Established Church of Scotland". That same year the "Presbytery of the Canadas", having grown and been re-organized, became the "United Synod of Upper Canada". In its continued pursuit for Presbyterian unity (and a share of government funding from the clergy reserves for established churches) the United Synod sought a union with the Church of Scotland synod which it finally joined in 1840. However, some ministers had left the United Synod prior to this merger (including, notably, Rev. James Harris, Rev. William Jenkins, and Rev. Daniel Eastman). In the 1832 new Secessionist missionaries began to arrive, belonging to "The United Associate Synod in Scotland" (after 1847, the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland). Committed to the voluntarist principle of rejecting government funding they decided against joining the "United Synod of Upper Canada" and on Christmas Day 1834 formed the "Missionary Presbytery of the Canadas". Although this new presbytery was formed at Rev. James Harris's church in Toronto, he and his congregation remained independent from it. However, the voluntarist, Rev. Jenkins and his congregation in Richmond Hill joined the Missionary Presbytery a few years later. Rev. Eastman had left the United Synod in 1833 to form the "Niagara Presbytery" of the Presbyterian Church in the USA. After this presbytery dissolved following the Rebellion of 1837, he rejoined the United Synod which then joined the Church of Scotland. Outside of these four Presbyterian denominations, only two others gained a foothold in the province. The small "Stamford Presbytery" of the American Secessionist tradition was formed in 1835 in the Niagara region, and the Scottish Reformed Presbyterian or "Covenanter" tradition was represented in the province to an even lesser extent. Despite the numerous denominations, by the late 1830s, the Church of Scotland was the main expression of Presbyterianism in Upper Canada.

Mennonites, Tunkers, Quakers, and Children of Peace

These groups of later Loyalists were proportionately larger in the early decades of the province's settlement. The Mennonites, Tunkers, Quakers and Children of Peace are the traditional Peace churches. The Mennonites and Tunkers were generally German-speaking and immigrated as Later Loyalists from Pennsylvania. Many of their descendants continue to speak a form of German called Pennsylvania Dutch. The Quakers (Society of Friends) immigrated from New York, the New England States and Pennsylvania. The Children of Peace were founded during the War of 1812 after a schism in the Society of Friends in York County.[56] A further schism occurred in 1828, leaving two branches, "Orthodox" Quakers and "Hicksite" Quakers.

Poverty

In the decade ending in 1837, the population of Upper Canada doubled, to 397,489, fed in large part by erratic spurts of displaced paupers, the "surplus population" of the British Isles. Historian Rainer Baehre estimated that between 1831 and 1835 a bare minimum of one-fifth of all emigrants to the province arrived totally destitute, forwarded by their parishes in the United Kingdom.[57] The pauper immigrants arriving in Toronto were the excess agricultural workers and artisans whose growing ranks sent the cost of parish-based poor relief in England spiralling; a financial crisis that generated frenetic public debate and the overhaul of the Poor Laws in 1834. "Assisted emigration", a second solution to the problem touted by the Parliamentary Under-Secretary in the Colonial Office, Robert Wilmot Horton, would remove them permanently from the parish poor rolls.

The roots of Wilmot-Horton's "assisted emigration" policies began in April 1820, in the middle of an insurrection in Glasgow, where a young, already twice bankrupted William Lyon Mackenzie was setting sail for Canada on a ship called Psyche. After the week-long violence, the rebellion was easily crushed; the participants were driven less by treason than distress. In a city of 147,000 people without a regular parish system of poor relief, between ten and fifteen thousand were destitute. The Prime Minister agreed to provide free transportation from Quebec to Upper Canada, a 100-acre (40 ha) land grant, and a year's supply of provisions to any of the rebellious weavers who could pay their own way to Quebec. In all, in 1820 and 1821, a private charity helped 2,716 Lanarkshire and Glasgow emigrants to Upper Canada to take up their free grants, primarily in the Peterborough area.[58] A second project was the Petworth Emigration Committee organised by the Reverend Thomas Sockett, who chartered ships and sent emigrants from England to Canada in each of the six years between 1832 and 1837.[59] This area in the south of England was terrorised by the Captain Swing Riots, a series of clandestine attacks on large farmers who refused relief to unemployed agricultural workers. The area hardest hit – Kent – was the area where Sir Francis Bond Head, later Lt. Governor of Upper Canada in 1836, was the Assistant Poor Law Commissioner. One of his jobs was to force the unemployed into "Houses of Industry."

Trade, monetary policy, and financial institutions

Corporations

There were two types of corporate actors at work in the Upper Canadian economy: the legislatively chartered companies and the unregulated joint-stock companies. The joint stock company was popular in building public works, since it should be for general public benefit, as the benefit would otherwise be sacrificed to legislated monopolies with exclusive privileges. or lie dormant. An example of the legislated monopoly is found in the Bank of Upper Canada. However, the benefit of the joint-stock shareholders, as the risk takers, was whole and entire; and the general public benefitted only indirectly. As late as 1849, even the moderate reform politician Robert Baldwin was to complain that "unless a stop were made to it, there would be nothing but corporations from one end of the country to the other." Radical reformers, like William Lyon Mackenzie, who opposed all "legislated monopolies," saw joint stock associations as the only protection against "the whole property of the country... being tied up as an irredeemable appendage to incorporated institutions, and put beyond the reach of individual possession."[60] As a result, most of the joint-stock companies formed in this period were created by political reformers who objected to the legislated monopolies granted to members of the Family Compact.

Currency and banking

Currency

The government of Upper Canada never issued a provincial currency. A variety of coins, mainly of French, Spanish, English and American origin circulated. The government used the Halifax standard, where one pound Halifax equalled four Spanish dollars. One pound sterling equalled £1 2s 2¾d (until 1820), and £1 2s 6½d Halifax pounds after 1820.

Paper currency was issued primarily by the Bank of Upper Canada, although with the diversification of the banking system, each bank would issue its own distinctive notes.[61]

Bank of Upper Canada

The Bank of Upper Canada was "captured" from Kingston merchants by the York elite at the instigation of John Strachan in 1821, with the assistance of William Allan, a Toronto merchant and Executive Councillor. York was too small to warrant such an institution as indicated by the inability of its promoters to raise even the minimal 10% of the £200,000 authorised capital required for start-up. It succeeded where the Bank of Kingston had failed only because it had the political influence to have this minimum reduced by half, and because the provincial government subscribed for two thousand of its eight thousand shares. The administration appointed four of the bank's fifteen directors that, as with the Clergy Corporation, made for a tight bond between the nominally private company and the state. Forty-four men served as bank directors during the 1830s; eleven of them were executive councillors, fifteen of them were legislative councillors, and thirteen were magistrates in Toronto. More importantly, all 11 men who had ever sat on the Executive Council also sat on the board of the Bank at one time or another. 10 of these men also sat on the Legislative Council. The overlapping membership on the boards of the Bank of Upper Canada and on the Executive and Legislative Councils served to integrate the economic and political activities of church, state, and the "financial sector." These overlapping memberships reinforced the oligarchic nature of power in the colony and allowed the administration to operate without any effective elective check. The Bank of Upper Canada was a political sore point for the Reformers throughout the 1830s.[62]

Bank wars: the Scottish joint-stock banks

The difference between the chartered banks and the joint-stock banks lay almost entirely on the issue of liability and its implications for the issuance of bank notes. The joint-stock banks lacked limited liability, hence every partner in the bank was responsible for the bank's debts to the full extent of their personal property. The formation of new joint-stock banks blossomed in 1835 in the aftermath of a parliamentary report by Dr Charles Duncombe, which established their legality here. Duncombe's report drew in large part on an increasingly dominant banking orthodoxy in the United Kingdom which challenged the English system of chartered banks. Duncombe's Select Committee on Currency offered a template for the creation of joint-stock banks based on several successful British banks. Within weeks two Devonshire businessmen, Capt. George Truscott and John Cleveland Green, established the "Farmer's Bank" in Toronto. The only other successful bank established under this law was "The Bank of the People" which was set up by Toronto's Reformers. The Bank of the People provided the loan that allowed William Lyon Mackenzie to establish the newspaper The Constitution in 1836 in the lead up to the Rebellion of 1837. Mackenzie wrote at the time: "Archdeacon Strachan's bank (the old one) ... serve the double purpose of keeping the merchants in chains of debt and bonds to the bank manager, and the Farmer's acres under the harrow of the storekeeper. You will be shewn how to break this degraded yoke of mortgages, ejectments, judgments and bonds. Money bound you – money shall loose you".[63] During the financial panic of 1836, the Family Compact sought to protect its interests in the nearly bankrupt Bank of Upper Canada by making joint-stock banks illegal.[64]

Trade

After the Napoleonic Wars, as industrial production in Britain took off, English manufacturers began dumping cheap goods in Montreal; this allowed an increasing number of shopkeepers in York to obtain their goods competitively from Montreal wholesalers. It was during this period that the three largest pre-war merchants who imported directly from Britain retired from business as a result; Quetton St. George in 1815, Alexander Wood in 1821, and William Allan in 1822. Toronto and Kingston then underwent a boom in the number of increasingly specialised shops and wholesalers.[65] The Toronto wholesale firm of Isaac Buchanan and Company were one of the largest of the new wholesalers. Isaac Buchanan was a Scots merchant in Toronto, in partnership with his brother Peter, who remained in Glasgow to manage the British end of the firm. They established their business in Toronto in 1835, having bought out Isaac's previous partners, William Guild and Co., who had established themselves in Toronto in 1832. As a wholesale firm, the Buchanan's had invested more than £10,000 in their business.[66]

Another of those new wholesale businesses was the Farmers' Storehouse Company. The Farmers Storehouse Company was formed in the Home District and is probably Canada's first Farmers' Cooperative. The Storehouse expedited the sale of farmer's wheat to Montreal, and provided them with cheaper consumer goods.[67]

Wheat and grains

Upper Canada was in the unenviable position of having few exports with which to pay for all its imported manufactured needs. For the vast majority of those who settled in rural areas, debt could be paid off only through the sale of wheat and flour; yet, throughout much of the 1820s, the price of wheat went through periodic cycles of boom and bust depending upon the British markets that ultimately provided the credit upon which the farmer lived. In the decade 1830–39, exports of wheat averaged less than £1 per person a year (less than £6 per household), and in the 1820s just half that.[68]

Given the small amounts of saleable wheat and flour, and the rarity of cash, some have questioned how market oriented these early farmers were. Instead of depending on the market to meet their needs, many of these farmers depended on networks of shared resources and cooperative marketing. For example, rather than hire labour, they met their labour needs through "work bees." such farmers are said to be 'subsistence oriented' and not to respond to market cues; rather, they engage in a moral economy seeking 'subsistence insurance' and a 'just price'. The Children of Peace in the village of Hope (now Sharon) are a well documented example. They were the most prosperous agricultural community in Canada West by 1851.[69]

Timber

The Ottawa River timber trade resulted from Napoleon's 1806 Continental Blockade in Europe. The United Kingdom required a new source of timber for its navy and shipbuilding. Later the UK's application of gradually increasing preferential tariffs increased Canadian imports. The trade in squared timber lasted until the 1850s. The transportation of raw timber by means of floating down the Ottawa River was proved possible in 1806 by Philemon Wright.[70] Squared timber would be assembled into large rafts which held living quarters for men on their six-week journey to Quebec City, which had large exporting facilities and easy access to the Atlantic Ocean.

The timber trade was Upper and Lower Canada's major industry in terms of employment and value of the product.[71] The largest supplier of square red and white pine to the British market was the Ottawa River[72] and the Ottawa Valley. They had "rich red and white pine forests."[73] Bytown (later called Ottawa), was a major lumber and sawmill centre of Canada.[74]

Transportation and communications

Canal system

The early nineteenth century was the age of canals. The Erie Canal, stretching from Buffalo to Albany, New York, threatened to divert all of the grain and other trade on the upper Great Lakes through the Hudson River to New York city after its completion in 1825. Upper Canadians sought to build a similar system that would tie this trade to the St Lawrence River and Montreal.

Rideau Canal

The Rideau Canal's purpose was military and hence was paid for by the British and not the local treasury. It was intended to provide a secure supply and communications route between Montreal and the British naval base in Kingston. The objective was to bypass the St. Lawrence River bordering New York; a route which would have left British supply ships vulnerable to an attack. Westward from Montreal, travel would proceed along the Ottawa River to Bytown (now Ottawa), then southwest via the canal to Kingston and out into Lake Ontario. Because the Rideau Canal was easier to navigate than the St. Lawrence River due to the series of rapids between Montreal and Kingston, it became a busy commercial artery from Montreal to the Great Lakes. The construction of the canal was supervised by Lieutenant-Colonel John By of the Royal Engineers. The work started in 1826, and was completed 6 years later in 1832 at a cost of £822,000.

Welland Canal

The Welland Canal was created to directly link Lake Erie with Lake Ontario, bypassing Niagara Falls and the Erie Canal. It was the idea of William Hamilton Merritt who owned a sawmill, grist mill and store on the Twelve Mile Creek. The Legislature authorised the joint-stock Welland Canal Company on 19 January 1824, with a capitalisation of $150,000, and Merritt as the agent. The canal was officially opened exactly five years later on 30 November 1829. However, the original route to Lake Erie followed the Welland and Niagara Rivers and was difficult and slow to navigate. The Welland Canal Company obtained a loan of 50,000 pounds from the province of Upper Canada in March 1831 to cut a canal directly to Gravelly Bay (now Port Colborne) as the new Lake Erie terminus for the canal.[75]

By the time the canal was finished in 1837, it had cost the province £425,000 in loans and stock subscriptions. The company was supposed to have been a private one using private capital; but the province had little private capital available, hence most of the original funds came from New York. To keep the canal in Upper Canadian hands, the province had passed a law barring Americans from the company's directorate. The company was thus controlled by the Family Compact, even though they had few shares. By 1834, it was clear the canal would never make money and that the province would be on the hook for the large loans; the canal and the canal company thus became a political issue, as local farmers argued the huge expense would ultimately only benefit American farmers in the west and the merchants who transported their grain.[76]

Desjardins Canal

The Desjardins Canal, named after its promoter Pierre Desjardins, was built to give Dundas, Ontario, easier access to Burlington Bay and Lake Ontario. Access to Lake Ontario from Dundas was made difficult by the topography of the area, which included a natural sand and gravel barrier, across Burlington Bay which allowed only boats with a shallow draft through. In 1823 a canal was dug through the sandbar. In 1826 the passage was completed, allowing schooners to sail to neighbouring Hamilton. Hamilton then became a major port and quickly expanded as a centre of trade and commerce. In 1826 a group of Dundas businessmen incorporated to compete with Hamilton and increase the value of their real estate holdings. The project to build Desjardins Canal continued for ten years, from 1827 to 1837, and required constant infusions of money from the province. In 1837, the year it opened, the company's income was £6,000, of which £5,000 was from a government loan and £166 was received from canal tolls.

Lake traffic: steamships

There is disagreement as to whether the Canadian-built Frontenac (170 feet; 52 m), launched on 7 September 1816, at Ernestown, Ontario or the US-built Ontario (110 feet; 34 m), launched in the spring of 1817 at Sacketts Harbor, New York, was the first steamboat on the Great Lakes. While Frontenac was launched first, Ontario began active service first.[77] The first steamboat on the upper Great Lakes was the passenger-carrying Walk-In-The-Water, built in 1818 to navigate Lake Erie.

In the years between 1809 and 1837 just over 100 steamboats were launched by Upper and Lower Canadians for the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes trade, of which ten operated on Lake Ontario.[78] The single largest engine foundry in British North America before 1838 was the Eagle Foundry of Montreal, founded by John Dod Ward in the fall of 1819 which manufactured 33 of the steam engines. The largest Upper Canadian engine manufacturer was Sheldon & Dutcher of Toronto, who made three engines in the 1830s before being driven to Bankruptcy by the Bank of Upper Canada in 1837.[79]

The major owner-operators of steamships on Lake Ontario were Donald Bethune, John Hamilton, Hugh Richardson, and Henry Gildersleeve, each of whom would have invested a substantial fortune.[80]

Roads

Besides marine travel, Upper Canada had a few Post roads or footpaths used for transportation by horse or stagecoaches along the key settlements between London to Kingston.

The Governor's Road was built beginning in 1793 from Dundas to Paris and then to the proposed capital of London by 1794. The road was further extended eastward with new capital of York in 1795. his road was eventually known as Dundas Road.

A second route was known as Lakeshore Road or York Road which was built from York to Trent River from 1799 to 1900 and later extended eastwards to Kingston in 1817. This road was later renamed as Kingston Road.

United States relations

War of 1812 (1812–1815)

During the War of 1812 with the United States, Upper Canada was the chief target of the Americans, since it was weakly defended and populated largely by American immigrants. However, division in the United States over the war, a lackluster American militia, the incompetence of American military commanders, and swift and decisive action by the British commander, Sir Isaac Brock, kept Upper Canada part of British North America.

Detroit was captured by the British on 6 August 1812. The Michigan Territory was held under British control until it was abandoned in 1813. The Americans won the decisive Battle of Lake Erie (10 September 1813) and forced the British to retreat from the western areas. On the retreat they were intercepted at the Battle of the Thames (5 October 1813) and destroyed in a major American victory that killed Tecumseh and broke the power of Britain's Indian allies.[81]

Major battles fought on territory in Upper Canada included:

- Battle of Queenston Heights, 13 October 1812

- Burning and Battle of York, 27 April 1813

- Battle of Fort George, 27 May 1813

- Battle of Stoney Creek, 5 June 1813

- Battle of Beaver Dams, 24 June 1813

- Battle of Lake Erie, 10 September 1813

- Battle of the Thames, 5 October 1813

- Battle of Crysler's Farm, 11 November 1813

- Burning of Newark, 10 December 1813

- Battle of Chippawa, 5 July 1814

- Battle of Lundy's Lane, 25 July 1814

Many other battles were fought in American territory bordering Upper Canada, including the Northwest Territory (most in modern-day Michigan), upstate New York and naval battles in the Great Lakes.

The Treaty of Ghent (ratified in 1815) ended the war and restored the status quo ante bellum.

1837 Rebellion and Patriot War

Mackenzie, Duncombe, John Rolph and 200 supporters fled to Navy Island in the Niagara River, where they declared themselves the Republic of Canada on 13 December. They obtained supplies from supporters in the United States, resulting in British reprisals (see Caroline affair). This incident has been used to establish the principle of "anticipatory self-defense" in international politics, which holds that it may be justified only in cases in which the "necessity of that self-defense is instant, overwhelming, and leaving no choice of means, and no moment for deliberation". This formulation is part of the Caroline test. The Caroline affair is also now invoked frequently in the course of the dispute around preemptive strike (or preemption doctrine).

On 13 January 1838, under attack by British armaments, the rebels fled. Mackenzie went to the United States where he was arrested and charged under the Neutrality Act.[82] The Neutrality Act of 1794 made it illegal for an American to wage war against any country at peace with the United States. Application of the Neutrality Act during the Patriot War led to the largest use of US government military force against its own citizens since the Whiskey Rebellion.[83]

The extended series of incidents comprising the Patriot War were finally settled by US Secretary of State Daniel Webster and Alexander Baring, 1st Baron Ashburton, in the course of their negotiations leading to the Webster–Ashburton Treaty of 1842.

Education

In 1807, the Grammar School Act allowed the government to take over various grammar schools across the province and incorporating them into a network of eight new, public grammar schools (secondary schools), one for each of the eight districts (Eastern, Johnstown, Midland, Newcastle, Home, Niagara, London, and Western):[84]

- Eastern Grammar School in New Johnstown or current day Cornwall, Ontario – founded as Cornwall Grammar School and later became Cornwall Collegiate and Vocational School.

- Johnstown District Grammar School, Maitland, Ontario

- Midland Grammar School – created to replace Kingston Grammar School established in 1792 and later became Kingston Collegiate and Vocational Institute

- Newcastle District Grammar School, Coburg

- Home District Grammar School in York, Upper Canada, later becoming Royal Grammar School, Toronto High School and finally to the current name Jarvis Collegiate Institute.

- St. Catherine's and District Grammar School (Niagara District)

- London District Grammar School latter became London Central Secondary School

- Western District Grammar School in Sandwich or current day Windsor, Ontario – grammar school is gone and is now the site of General Brock Public School.[85]

Canada West

Canada West was the western portion of the United Province of Canada from 10 February 1841, to 1 July 1867.[86] Its boundaries were identical to those of the former province of Upper Canada. Lower Canada would also become Canada East.

The area was named the province of Ontario under the British North America Act of 1867.

See also

Notes

- ^ "Early flags". Government of Canada. 28 August 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ "Royal Union Flag". The Flags of Canada. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ Section 38, Constitutional Act, 1791, Revised Statutes of Canada 1985, App. II, No. 3.

- ^ a b Butler (1843), pp. 10, 20

- ^ "Juriglobe".

- ^ "Constitutional Act 1791". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Craig (1963), p. 2

- ^ Craig (1963), pp. 5–6

- ^ Craig (1963), p. 6

- ^ "Biography – SIMCOE, JOHN GRAVES". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. V. 1801–1820.

- ^ McNairn (2000), pp. 23–62

- ^ Armstrong (1985), pp. 8–12

- ^ Armstrong (1985), p. 39

- ^ Craig (1963), p. 12;George W. Spragge, "The Districts of Upper Canada, 1788-1849," in Profiles of a Province: Studies in Ontario History, (Toronto: Ontario Historical Society, 1967), 34-42, maps.

- ^ Craig (1963), pp. 30–31

- ^ Wallace (1915)

- ^ Mills, David; Panneton, Daniel (20 March 2017) [7 February 2006]. "Family Compact". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ "Biography – ROBINSON, Sir JOHN BEVERLEY". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IX. 1861–1870.

- ^ "Biography – BOULTON, WILLIAM HENRY". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. X. 1871–1880.

- ^ Craig (1963), pp. 93–99

- ^ Wilton (2001), pp. 146–147

- ^ Schrauwers (2009), pp. 181–184

- ^ Schrauwers (2009), pp. 192–199

- ^ Greer, Allan (1995). "1837–38: Rebellion Reconsidered". Canadian Historical Review. LXVII (1): 1–30. doi:10.3138/chr-076-01-01.

- ^ Careless (1967), pp. 113–30

- ^ McKay, Ian (2000). "The Liberal Order Framework: A prospectus for a reconnaissance of Canadian History". Canadian Historical Review. 81 (4): 616–678. doi:10.3138/chr.81.4.616. S2CID 162365787.

- ^ a b Haudenosaunee is /hɔːdɛnəˈʃɔːniː/ in English, Akunęhsyę̀niˀ in Tuscarora (Rudes, B., Tuscarora English Dictionary, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), and Rotinonsionni in Mohawk.

- ^ "Upper Canada Land Surrenders". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Mintz (1999)

- ^ a b "Upper Canada Land Surrenders and the Williams Treaties (1764-1862/1923)". www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. 15 February 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Gates (1968)

- ^ Calton is now within Glasgow itself.

- ^ Campey (2005), p. 52ff

- ^ Humber (1991), p. 193

- ^ Craig (1963), pp. 142–144

- ^ Craig (1963), pp. 171–179

- ^ Wilson, George A. (1959). The Political and Administrative History of the Upper Canada Clergy Reserves, 1790–1855. Toronto: PhD Thesis, Dept. of History, University of Toronto. pp. 133ff.

- ^ a b Hayes, Alan L. (2004). Anglicans in Canada: Controversies and Identity in Historical Perspective. Urba and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. pp. 59–61. ISBN 0-252-02902-X.

- ^ Wilson, Alan (1969). The Clergy Reserves of Upper Canada (PDF). Historical Booklet No. 23. Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association. p. 17. ISBN 0-88798-057-0. ISSN 0068-886X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Attorney-General v Grasett, 5 Gr 412 (C.C.U.C. 12 May 1856).; affirmed on appeal, Attorney-General v Grasett, 6 Gr 200 (C.E.A.U.C. 1857).

- ^ An Act to provide for the sale of the Rectory Lands in this Province, S.Prov.C. 1866, c. 16 , as amended by c. 17

- ^ The Origin, History and Management of the University of King's College. Toronto: George Brown. 1844. p. 9.

- ^ Hodgins, J. George (1894). "V: Educational Provisions of the Upper Canada Legislature in 1832, 1833". Documentary History of Education in Upper Canada. Vol. II (1831-1836). Toronto: Warwick Bros. & Rutter. pp. 102–105.

- ^ Schrauwers, Albert (Spring 2010). "The Gentlemanly Order & the Politics of Production in the Transition to Capitalism in the Home District, Upper Canada". Labour/Le Travail. 65 (1): 26–31. JSTOR 20798984.

- ^ Lee (2004), pp. 98–148

- ^ Ankli, Robert E.; Duncan, Kenneth (1984). "Farm Making Costs in Early Ontario". Canadian Papers in Rural History. 4: 33–49.

- ^ "What was the Huron Tract?". Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ "Complete History of the Canadian Metis Culturework=Metis nation of the North West". Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ Cooper, Afua, "Acts of Resistance: Black Men and Women Engage Slavery in Upper Canada, 1793–1803," Ontario History, Spring 2007, Vol. 99 Issue 1, pp 5–17

- ^ "Underground Railroad". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Wilton (2001), p. 9

- ^ "The Parish of St. Raphael Glengarry Emigration of 1786 Bishop Alexander Macdonell 1762–1840". ontarioplaques.com. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ "Multiculturalism". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ "Why is Canada the most tolerant country in the world? Luck".

- ^ "Bishop Alexander MacDonell". catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ Reaman (1957), pp. 40–124

- ^ Baehre, Rainer (1981). "Pauper Emigration to Upper Canada in the 1830s". Historie Sociale/Social History. XIV (28): 340.

- ^ Johnston (1972), pp. 51–54

- ^ Cameron & Maude (2000)

- ^ Schrauwers (2009), p. 21

- ^ McCalla (1993), pp. 245247

- ^ Schrauwers (2010), pp. 22–26

- ^ Schrauwers, Albert (2011). "'Money bound you – money shall loose you': Micro-credit, Social Capital and the Meaning of Money in Upper Canada". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 52 (2): 314–343. doi:10.1017/s0010417511000077. S2CID 154484234.

- ^ Schrauwers (2009), pp. 151–174

- ^ Schrauwers (2009), p. 107

- ^ McCalla (1979), p. 28

- ^ Schrauwers (2009), pp. 102–106

- ^ McCalla (1993), p. 75

- ^ Schrauwers (2009), pp. 41–50

- ^ Woods (1980), p. 89

- ^ Greening (1961), pp. 111

- ^ Greening (1961), p. 111

- ^ Bond (1984), p. 43

- ^ (Mika 1982, p. 121)

- ^ Craig (1963), pp. 153–160

- ^ Aitken, Hugh G.T. (1953). "Yates and McIntyre: Lottery Managers". The Journal of Economic History. 13 (1): 36–57. doi:10.1017/S0022050700070030. S2CID 153540099.

- ^ The debate is addressed by Barlow Cumberland in Chapter 2 of A Century of Sail and Steam on the Niagara River. Retrieved 26 March 2011

- ^ McCalla (1993), p. 119

- ^ Lewis, Walter (1997). "The First Generation of Marine Engines in Central Canadian Steamers, 1809–1837". The Northern Mariner. VII (2): II.

- ^ McCalla (1993), p. 120

- ^ Young, Bennett Henderson, The Battle of the Thames: In Which Kentuckians Defeated the British, French and Indians, 5 October 1813. Louisville, Ky.: Morton, 1903.

- ^ Armstrong, Frederick H.; Stagg, Ronald J. (1976). "McKenzie, William Lyon". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IX (1861–1870) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Bonthius, Andrew (2003). "The Patriot War of 1837–1838: Locofocoism with a Gun?". Labour/Le Travail. 52 (2): 11–12. doi:10.2307/25149383. JSTOR 25149383. S2CID 142863197.

- ^ "Education in Upper Canada From 1783 To 1844". canada.yodelout.com.

- ^ "Western District Grammar School – Southwestern Ontario Digital Archive". swoda.uwindsor.ca.

- ^ Careless, J.M.S.; Foot, Richard (4 March 2015) [7 February 2006]. "Province of Canada, 1841–67". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada.

References

- Armstrong, Frederick Henry (1985). Handbook of Upper Canadian Chronology (revised ed.). Dundurn. ISBN 978-0-919670-92-1.

- Bond, Courtney C.J. (1984). Where Rivers Meet: An Illustrated History of Ottawa. Windsor Publications.

- Butler, Samuel (1843). The Emigrant's Handbook of Facts Concerning Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Cape of Good Hope, &c. Glasgow: W.R. M'Phun. ISBN 9780665952821.

- Cameron, Wendy; Maude, Mary McDougall (2000). Assisting Emigration to Upper Canada: The Petworth Project, 1832–1837. Montreal-Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 9780773520349.

- Campey, Lucille H. (2005). The Scottish pioneers of Upper Canada, 1784–1855: Glengarry and beyond. Dundurn Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1-897045-01-5.

- Careless, J.M.S. (1967). The Union of the Canadas: The Growth of Canadian Institutions 1841–1857. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 9780771019128.

- Craig, Gerald M. (1963). Upper Canada: The Formative Years, 1784-1841, republished 2013. McClelland and Stewart. ISBN 978-0-19-900904-6.

- Gates, Lillian (1968). Land Policies of Upper Canada. Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press.

- Greening, W.E. (1961). The Ottawa. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart.

- Humber, Charles J. (1991). Allegiance: the Ontario Story. Mississauga, Ontario: Heirloom Publishing.

- Johnston, H.J.M. (1972). British Emigration Policy 1815–1830: 'Shovelling Out the Paupers. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Lee, Robert C. (2004). The Canada Company and the Huron Tract, 1826–1853: Personalities, Profits and Politics. Toronto: Natural Heritage Books. ISBN 9781896219943.

- McCalla, Douglas (1979). The Upper Canada Trade 1834–1872: A Study of the Buchanan's Business. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- McCalla, Douglas (1993). Planting the Province: The Economic History of Upper Canada 1784–1870. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- McNairn, Jeffrey L. (2000). The Capacity To Judge: Public Opinion and Deliberative Democracy in Upper Canada,1791-1854. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-3916-4.

- Mika, Nick & Helma (1982). Bytown: The Early Days of Ottawa. Belleville, Ont.: Mika Publishing Company.

- Mintz, Max M. (1999). Seeds of Empire: The American Revolutionary Conquest of the Iroquois. New York University Press.

- Reaman, G. Elmore (1957). The Trail of the Black Walnut. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart.

- Schrauwers, Albert (2009). Union is Strength: W.L. Mackenzie, the Children of Peace and the Emergence of Joint Stock Democracy in Upper Canada. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9927-3.

- Spragge, George W. "The Districts of Upper Canada, 1788-1849," in Profiles of a Province: Studies in Ontario History, (Toronto: Ontario Historical Society, 1967), 34-42, originally published in Ontario History, XXXIX (1947), 91-100.

- Wallace, W. Stewart (1915). The Family Compact: A Chronicle of the Rebellion in Upper Canada. Glasgow, Brook.

- Wilton, Carol (2001). Popular Politics and Political Culture in Upper Canada, 1800-1850. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2054-7.

- Woods, Shirley E. Jr (1980). Ottawa: The Capital of Canada. Toronto: Doubleday Canada.

Statutes

- Stewart Derbishire and George Desbarats, printers (1859). The consolidated statutes for Upper Canada. Toronto: Toronto : Printed by S. Derbishire and G. Desbarats, law printer to the Queen.

- James Nickalls Jr (1831). The Statutes of the Province of Upper Canada: Together with Such British Statutes, Ordinances of Quebec, and Proclamationsas relate to the said province. Kingston: Printed by F.M. Hill.

Further reading

- Clarke, John. Land Power and Economics on the Frontier of Upper Canada McGill-Queen's University Press (2001) 747pp. (ISBN 0-7735-2062-7)

- Di Mascio, Anthony. The Idea of Popular Schooling in Upper Canada: Print Culture, Public Discourse, and the Demand for Education (McGill-Queen's University Press; 2012) 248 pages; building a common system of schooling in the late-18th and early 19th centuries.

- Dieterman, Frank. Government on fire: the history and archaeology of Upper Canada's first Parliament Buildings Eastendbooks, 2001.

- Dunham, Eileen. Political unrest in Upper Canada 1815–1836 McClelland and Stewart, 1963.

- Errington, Jane. The lion, the eagle, and Upper Canada: a developing colonial ideology McGill-Queen's University Press, 1987.

- Grabb, Edward; Duncan, Jeff; Baer, Douglas (2000). "Defining Moments and Recurring Myths: Comparing Canadians and Americans after the American Revolution". The Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology. 37 (4): 373–419. doi:10.1111/j.1755-618X.2000.tb00595.x.