United States Bill of Rights

| United States Bill of Rights | |

|---|---|

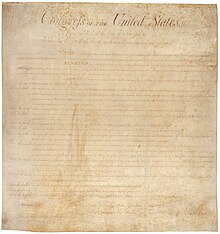

First page of an original copy of the twelve proposed articles of amendment, as passed by Congress | |

| Created | September 25, 1789 |

| Ratified | December 15, 1791 |

| Location | National Archives |

| Author(s) | 1st United States Congress, mainly James Madison |

| Purpose | To amend the Constitution of the United States |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States |

|---|

|

| Preamble and Articles |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

Unratified Amendments: |

| History |

| Full text |

The United States Bill of Rights comprises the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution. Proposed following the often bitter 1787–88 debate over the ratification of the Constitution and written to address the objections raised by Anti-Federalists, the Bill of Rights amendments add to the Constitution specific guarantees of personal freedoms and rights, clear limitations on the government's power in judicial and other proceedings, and explicit declarations that all powers not specifically granted to the federal government by the Constitution are reserved to the states or the people. The concepts codified in these amendments are built upon those in earlier documents, especially the Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776), as well as the Northwest Ordinance (1787),[1] the English Bill of Rights (1689), and Magna Carta (1215).[2]

Largely because of the efforts of Representative James Madison, who studied the deficiencies of the Constitution pointed out by Anti-Federalists and then crafted a series of corrective proposals, Congress approved twelve articles of amendment on September 25, 1789, and submitted them to the states for ratification. Contrary to Madison's proposal that the proposed amendments be incorporated into the main body of the Constitution (at the relevant articles and sections of the document), they were proposed as supplemental additions (codicils) to it.[3] Articles Three through Twelve were ratified as additions to the Constitution on December 15, 1791, and became Amendments One through Ten of the Constitution. Article Two became part of the Constitution on May 5, 1992, as the Twenty-seventh Amendment. Article One is still pending before the states.

Although Madison's proposed amendments included a provision to extend the protection of some of the Bill of Rights to the states, the amendments that were finally submitted for ratification applied only to the federal government. The door for their application upon state governments was opened in the 1860s, following ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment. Since the early 20th century both federal and state courts have used the Fourteenth Amendment to apply portions of the Bill of Rights to state and local governments. The process is known as incorporation.[4]

James Madison initially opposed the idea of creating a bill of rights, primarily for two reasons:

1. The Constitution did not grant the federal government the power to take away people’s rights. The federal government’s powers are “few and defined” (listed in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution). Any powers not listed in the Constitution reside with the states or the people themselves.[5][6][7]

2. By creating a list of people’s rights, then anything not on the list was therefore not protected. Madison and the other Framers believed that we have natural rights and they are too numerous to list. So, writing a list would be counterproductive.[8][9]

However, opponents of the ratification of the Constitution objected that it contained no bill of rights. So, in order to secure ratification, Madison agreed to support adding a bill of rights, and even served as its author. He resolved the dilemma mentioned in Item 2 above by including the 9th Amendment, which states that just because a right hasn’t been listed in the Bill of Rights doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist.[10]

There are several original engrossed copies of the Bill of Rights still in existence. One of these is on permanent public display at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

Background

Philadelphia Convention

I go further, and affirm that bills of rights, in the sense and to the extent in which they are contended for, are not only unnecessary in the proposed Constitution, but would even be dangerous. They would contain various exceptions to powers not granted; and, on this very account, would afford a colorable pretext to claim more than were granted. For why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do? Why, for instance, should it be said that the liberty of the press shall not be restrained, when no power is given by which restrictions may be imposed? I will not contend that such a provision would confer a regulating power; but it is evident that it would furnish, to men disposed to usurp, a plausible pretense for claiming that power. They might urge with a semblance of reason, that the Constitution ought not to be charged with the absurdity of providing against the abuse of an authority which was not given, and that the provision against restraining the liberty of the press afforded a clear implication, that a power to prescribe proper regulations concerning it was intended to be vested in the national government. This may serve as a specimen of the numerous handles which would be given to the doctrine of constructive powers, by the indulgence of an injudicious zeal for bills of rights.

Prior to the ratification and implementation of the United States Constitution, the thirteen sovereign states followed the Articles of Confederation, created by the Second Continental Congress and ratified in 1781. However, the national government that operated under the Articles of Confederation was too weak to adequately regulate the various conflicts that arose between the states.[11] The Philadelphia Convention set out to correct weaknesses of the Articles that had been apparent even before the American Revolutionary War had been successfully concluded.[11]

The convention took place from May 14 to September 17, 1787, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Although the Convention was purportedly intended only to revise the Articles, the intention of many of its proponents, chief among them James Madison of Virginia and Alexander Hamilton of New York, was to create a new government rather than fix the existing one. The convention convened in the Pennsylvania State House, and George Washington of Virginia was unanimously elected as president of the convention.[12] The 55 delegates who drafted the Constitution are among the men known as the Founding Fathers of the new nation. Thomas Jefferson, who was Minister to France during the convention, characterized the delegates as an assembly of "demi-gods."[11] Rhode Island refused to send delegates to the convention.[13]

On September 12, George Mason of Virginia suggested the addition of a Bill of Rights to the Constitution modeled on previous state declarations, and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts made it a formal motion.[14] However, after only a brief discussion where Roger Sherman pointed out that State Bills of Rights were not repealed by the new Constitution,[15][16] the motion was defeated by a unanimous vote of the state delegations. Madison, then an opponent of a Bill of Rights, later explained the vote by calling the state bills of rights "parchment barriers" that offered only an illusion of protection against tyranny.[17] Another delegate, James Wilson of Pennsylvania, later argued that the act of enumerating the rights of the people would have been dangerous, because it would imply that rights not explicitly mentioned did not exist;[17] Hamilton echoed this point in Federalist No. 84.[18]

Because Mason and Gerry had emerged as opponents of the proposed new Constitution, their motion—introduced five days before the end of the convention—may also have been seen by other delegates as a delaying tactic.[19] The quick rejection of this motion, however, later endangered the entire ratification process. Author David O. Stewart characterizes the omission of a Bill of Rights in the original Constitution as "a political blunder of the first magnitude"[19] while historian Jack N. Rakove calls it "the one serious miscalculation the framers made as they looked ahead to the struggle over ratification".[20]

Thirty-nine delegates signed the finalized Constitution. Thirteen delegates left before it was completed, and three who remained at the convention until the end refused to sign it: Mason, Gerry, and Edmund Randolph of Virginia.[21] Afterward, the Constitution was presented to the Articles of Confederation Congress with the request that it afterwards be submitted to a convention of delegates, chosen in each State by the people, for their assent and ratification.[22]

Anti-Federalists

Following the Philadelphia Convention, some leading revolutionary figures such as Patrick Henry, Samuel Adams, and Richard Henry Lee publicly opposed the new frame of government, a position known as "Anti-Federalism".[23] Elbridge Gerry wrote the most popular Anti-Federalist tract, "Hon. Mr. Gerry's Objections", which went through 46 printings; the essay particularly focused on the lack of a bill of rights in the proposed Constitution.[24] Many were concerned that a strong national government was a threat to individual rights and that the President would become a king. Jefferson wrote to Madison advocating a Bill of Rights: "Half a loaf is better than no bread. If we cannot secure all our rights, let us secure what we can."[25] The pseudonymous Anti-Federalist "Brutus" (probably Robert Yates)[26] wrote,

We find they have, in the ninth section of the first article declared, that the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless in cases of rebellion—that no bill of attainder, or ex post facto law, shall be passed—that no title of nobility shall be granted by the United States, etc. If every thing which is not given is reserved, what propriety is there in these exceptions? Does this Constitution any where grant the power of suspending the habeas corpus, to make ex post facto laws, pass bills of attainder, or grant titles of nobility? It certainly does not in express terms. The only answer that can be given is, that these are implied in the general powers granted. With equal truth it may be said, that all the powers which the bills of rights guard against the abuse of, are contained or implied in the general ones granted by this Constitution.[27]

He continued with this observation:

Ought not a government, vested with such extensive and indefinite authority, to have been restricted by a declaration of rights? It certainly ought. So clear a point is this, that I cannot help suspecting that persons who attempt to persuade people that such reservations were less necessary under this Constitution than under those of the States, are wilfully endeavoring to deceive, and to lead you into an absolute state of vassalage.[28]

Federalists

Supporters of the Constitution, known as Federalists, opposed a bill of rights for much of the ratification period, in part because of the procedural uncertainties it would create.[29] Madison argued against such an inclusion, suggesting that state governments were sufficient guarantors of personal liberty, in No. 46 of The Federalist Papers, a series of essays promoting the Federalist position.[30] Hamilton opposed a bill of rights in The Federalist No. 84, stating that "the constitution is itself in every rational sense, and to every useful purpose, a bill of rights." He stated that ratification did not mean the American people were surrendering their rights, making protections unnecessary: "Here, in strictness, the people surrender nothing, and as they retain everything, they have no need of particular reservations." Patrick Henry criticized the Federalist point of view, writing that the legislature must be firmly informed "of the extent of the rights retained by the people ... being in a state of uncertainty, they will assume rather than give up powers by implication."[31] Other anti-Federalists pointed out that earlier political documents, in particular Magna Carta, had protected specific rights. In response, Hamilton argued that the Constitution was inherently different:

Bills of rights are in their origin, stipulations between kings and their subjects, abridgments of prerogative in favor of privilege, reservations of rights not surrendered to the prince. Such was the Magna Charta, obtained by the Barons, swords in hand, from King John.[32]

Massachusetts compromise

In December 1787 and January 1788, five states—Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, and Connecticut—ratified the Constitution with relative ease, though the bitter minority report of the Pennsylvania opposition was widely circulated.[33] In contrast to its predecessors, the Massachusetts convention was angry and contentious, at one point erupting into a fistfight between Federalist delegate Francis Dana and Anti-Federalist Elbridge Gerry when the latter was not allowed to speak.[34] The impasse was resolved only when revolutionary heroes and leading Anti-Federalists Samuel Adams and John Hancock agreed to ratification on the condition that the convention also propose amendments.[35] The convention's proposed amendments included a requirement for grand jury indictment in capital cases, which would form part of the Fifth Amendment, and an amendment reserving powers to the states not expressly given to the federal government, which would later form the basis for the Tenth Amendment.[36]

Following Massachusetts' lead, the Federalist minorities in both Virginia and New York were able to obtain ratification in convention by linking ratification to recommended amendments.[37] A committee of the Virginia convention headed by law professor George Wythe forwarded forty recommended amendments to Congress, twenty of which enumerated individual rights and another twenty of which enumerated states' rights.[38] The latter amendments included limitations on federal powers to levy taxes and regulate trade.[39]

A minority of the Constitution's critics, such as Maryland's Luther Martin, continued to oppose ratification.[40] However, Martin's allies, such as New York's John Lansing Jr., dropped moves to obstruct the Convention's process. They began to take exception to the Constitution "as it was", seeking amendments. Several conventions saw supporters for "amendments before" shift to a position of "amendments after" for the sake of staying in the Union. Ultimately, only North Carolina and Rhode Island waited for amendments from Congress before ratifying.[37]

Article Seven of the proposed Constitution set the terms by which the new frame of government would be established. The new Constitution would become operational when ratified by at least nine states. Only then would it replace the existing government under the Articles of Confederation and would apply only to those states that ratified it.

Following contentious battles in several states, the proposed Constitution reached that nine-state ratification plateau in June 1788. On September 13, 1788, the Articles of Confederation Congress certified that the new Constitution had been ratified by more than enough states for the new system to be implemented and directed the new government to meet in New York City on the first Wednesday in March the following year.[41] On March 4, 1789, the new frame of government came into force with eleven of the thirteen states participating.

New York Circular Letter

In New York, the majority of the Ratifying Convention was Anti-Federalist and they were not inclined to follow the Massachusetts Compromise. Led by Melancton Smith, they were inclined to make the ratification of New York conditional on prior proposal of amendments or, perhaps, insist on the right to secede from the union if amendments are not promptly proposed. Hamilton, after consulting with Madison, informed the Convention that this would not be accepted by Congress.

After ratification by the ninth state, New Hampshire, followed shortly by Virginia, it was clear the Constitution would go into effect with or without New York as a member of the Union. In a compromise, the New York Convention proposed to ratify, feeling confident that the states would call for new amendments using the convention procedure in Article V, rather than making this a condition of ratification by New York. John Jay wrote the New York Circular Letter calling for the use of this procedure, which was then sent to all the States. The legislatures in New York and Virginia passed resolutions calling for the convention to propose amendments that had been demanded by the States while several other states tabled the matter to consider in a future legislative session. Madison wrote the Bill of Rights partially in response to this action from the States.

Proposal and ratification

Anticipating amendments

Let me add that a bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular, and what no just government should refuse, or rest on inference.

The 1st United States Congress, which met in New York City's Federal Hall, was a triumph for the Federalists. The Senate of eleven states contained 20 Federalists with only two Anti-Federalists, both from Virginia. The House included 48 Federalists to 11 Anti-Federalists, the latter of whom were from only four states: Massachusetts, New York, Virginia and South Carolina.[43] Among the Virginia delegation to the House was James Madison, Patrick Henry's chief opponent in the Virginia ratification battle. In retaliation for Madison's victory in that battle at Virginia's ratification convention, Henry and other Anti-Federalists, who controlled the Virginia House of Delegates, had gerrymandered a hostile district for Madison's planned congressional run and recruited Madison's future presidential successor, James Monroe, to oppose him.[44] Madison defeated Monroe after offering a campaign pledge that he would introduce constitutional amendments forming a bill of rights at the First Congress.[45]

Originally opposed to the inclusion of a bill of rights in the Constitution, Madison had gradually come to understand the importance of doing so during the often contentious ratification debates. By taking the initiative to propose amendments himself through the Congress, he hoped to preempt a second constitutional convention that might, it was feared, undo the difficult compromises of 1787, and open the entire Constitution to reconsideration, thus risking the dissolution of the new federal government. Writing to Jefferson, he stated, "The friends of the Constitution, some from an approbation of particular amendments, others from a spirit of conciliation, are generally agreed that the System should be revised. But they wish the revisal to be carried no farther than to supply additional guards for liberty."[46] He also felt that amendments guaranteeing personal liberties would "give to the Government its due popularity and stability".[47] Finally, he hoped that the amendments "would acquire by degrees the character of fundamental maxims of free government, and as they become incorporated with the national sentiment, counteract the impulses of interest and passion".[48] Historians continue to debate the degree to which Madison considered the amendments of the Bill of Rights necessary, and to what degree he considered them politically expedient; in the outline of his address, he wrote, "Bill of Rights—useful—not essential—".[49]

On the occasion of his April 30, 1789 inauguration as the nation's first president, George Washington addressed the subject of amending the Constitution. He urged the legislators,

whilst you carefully avoid every alteration which might endanger the benefits of an united and effective government, or which ought to await the future lessons of experience; a reverence for the characteristic rights of freemen, and a regard for public harmony, will sufficiently influence your deliberations on the question, how far the former can be impregnably fortified or the latter be safely and advantageously promoted.[50][51]

Madison's proposed amendments

James Madison introduced a series of Constitutional amendments in the House of Representatives for consideration. Among his proposals was one that would have added introductory language stressing natural rights to the preamble.[52] Another would apply parts of the Bill of Rights to the states as well as the federal government. Several sought to protect individual personal rights by limiting various Constitutional powers of Congress. Like Washington, Madison urged Congress to keep the revision to the Constitution "a moderate one", limited to protecting individual rights.[52]

Madison was deeply read in the history of government and used a range of sources in composing the amendments. The English Magna Carta of 1215 inspired the right to petition and to trial by jury, for example, while the English Bill of Rights of 1689 provided an early precedent for the right to keep and bear arms (although this applied only to Protestants) and prohibited cruel and unusual punishment.[39]

The greatest influence on Madison's text, however, was existing state constitutions.[53][54] Many of his amendments, including his proposed new preamble, were based on the Virginia Declaration of Rights drafted by Anti-Federalist George Mason in 1776.[55] To reduce future opposition to ratification, Madison also looked for recommendations shared by many states.[54] He did provide one, however, that no state had requested: "No state shall violate the equal rights of conscience, or the freedom of the press, or the trial by jury in criminal cases."[56] He did not include an amendment that every state had asked for, one that would have made tax assessments voluntary instead of contributions.[57] Madison proposed the following constitutional amendments:

First. That there be prefixed to the Constitution a declaration, that all power is originally vested in, and consequently derived from, the people.

That Government is instituted and ought to be exercised for the benefit of the people; which consists in the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the right of acquiring and using property, and generally of pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.

That the people have an indubitable, unalienable, and indefeasible right to reform or change their Government, whenever it be found adverse or inadequate to the purposes of its institution.

Secondly. That in article 1st, section 2, clause 3, these words be struck out, to wit: "The number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every thirty thousand, but each State shall have at least one Representative, and until such enumeration shall be made;" and in place thereof be inserted these words, to wit: "After the first actual enumeration, there shall be one Representative for every thirty thousand, until the number amounts to—, after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that the number shall never be less than—, nor more than—, but each State shall, after the first enumeration, have at least two Representatives; and prior thereto."

Thirdly. That in article 1st, section 6, clause 1, there be added to the end of the first sentence, these words, to wit: "But no law varying the compensation last ascertained shall operate before the next ensuing election of Representatives."

Fourthly. That in article 1st, section 9, between clauses 3 and 4, be inserted these clauses, to wit: The civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship, nor shall any national religion be established, nor shall the full and equal rights of conscience be in any manner, or on any pretext, infringed.

The people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable.

The people shall not be restrained from peaceably assembling and consulting for their common good; nor from applying to the legislature by petitions, or remonstrances for redress of their grievances.

The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed; a well armed and well regulated militia being the best security of a free country: but no person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms shall be compelled to render military service in person.No soldier shall in time of peace be quartered in any house without the consent of the owner; nor at any time, but in a manner warranted by law.

No person shall be subject, except in cases of impeachment, to more than one punishment, or one trial for the same offence; nor shall be compelled to be a witness against himself; nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor be obliged to relinquish his property, where it may be necessary for public use, without a just compensation.

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.The rights of the people to be secured in their persons, their houses, their papers, and their other property, from all unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated by warrants issued without probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, or not particularly describing the places to be searched, or the persons or things to be seized.

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, to be informed of the cause and nature of the accusation, to be confronted with his accusers, and the witnesses against him; to have a compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor; and to have the assistance of counsel for his defence.

The exceptions here or elsewhere in the Constitution, made in favor of particular rights, shall not be so construed as to diminish the just importance of other rights retained by the people, or as to enlarge the powers delegated by the Constitution; but either as actual limitations of such powers, or as inserted merely for greater caution.

Fifthly. That in article 1st, section 10, between clauses 1 and 2, be inserted this clause, to wit: No State shall violate the equal rights of conscience, or the freedom of the press, or the trial by jury in criminal cases.

Sixthly. That, in article 3d, section 2, be annexed to the end of clause 2d, these words, to wit: But no appeal to such court shall be allowed where the value in controversy shall not amount to — dollars: nor shall any fact triable by jury, according to the course of common law, be otherwise re-examinable than may consist with the principles of common law.

Seventhly. That in article 3d, section 2, the third clause be struck out, and in its place be inserted the clauses following, to wit: The trial of all crimes (except in cases of impeachments, and cases arising in the land or naval forces, or the militia when on actual service, in time of war or public danger) shall be by an impartial jury of freeholders of the vicinage, with the requisite of unanimity for conviction, of the right with the requisite of unanimity for conviction, of the right of challenge, and other accustomed requisites; and in all crimes punishable with loss of life or member, presentment or indictment by a grand jury shall be an essential preliminary, provided that in cases of crimes committed within any county which may be in possession of an enemy, or in which a general insurrection may prevail, the trial may by law be authorized in some other county of the same State, as near as may be to the seat of the offence.

In cases of crimes committed not within any county, the trial may by law be in such county as the laws shall have prescribed. In suits at common law, between man and man, the trial by jury, as one of the best securities to the rights of the people, ought to remain inviolate.Eighthly. That immediately after article 6th, be inserted, as article 7th, the clauses following, to wit: The powers delegated by this Constitution are appropriated to the departments to which they are respectively distributed: so that the Legislative Department shall never exercise the powers vested in the Executive or Judicial, nor the Executive exercise the powers vested in the Legislative or Judicial, nor the Judicial exercise the powers vested in the Legislative or Executive Departments.

The powers not delegated by this Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the States respectively.

Ninthly. That article 7th, be numbered as article 8th.[58]

Crafting amendments

Federalist representatives were quick to attack Madison's proposal, fearing that any move to amend the new Constitution so soon after its implementation would create an appearance of instability in the government.[59] The House, unlike the Senate, was open to the public, and members such as Fisher Ames warned that a prolonged "dissection of the constitution" before the galleries could shake public confidence.[60] A procedural battle followed, and after initially forwarding the amendments to a select committee for revision, the House agreed to take Madison's proposal up as a full body beginning on July 21, 1789.[61][62]

The eleven-member committee made some significant changes to Madison's nine proposed amendments, including eliminating most of his preamble and adding the phrase "freedom of speech, and of the press".[63] The House debated the amendments for eleven days. Roger Sherman of Connecticut persuaded the House to place the amendments at the Constitution's end so that the document would "remain inviolate", rather than adding them throughout, as Madison had proposed.[64][65] The amendments, revised and condensed from twenty to seventeen, were approved and forwarded to the Senate on August 24, 1789.[66]

The Senate edited these amendments still further, making 26 changes of its own. Madison's proposal to apply parts of the Bill of Rights to the states as well as the federal government was eliminated, and the seventeen amendments were condensed to twelve, which were approved on September 9, 1789.[67] The Senate also eliminated the last of Madison's proposed changes to the preamble.[68]

On September 21, 1789, a House–Senate Conference Committee convened to resolve the numerous differences between the two Bill of Rights proposals. On September 24, 1789, the committee issued this report, which finalized 12 Constitutional Amendments for House and Senate to consider. This final version was approved by joint resolution of Congress on September 25, 1789, to be forwarded by John J. Beckley to the states on September 28.[69][70][71]

By the time the debates and legislative maneuvering that went into crafting the Bill of Rights amendments was done, many personal opinions had shifted. A number of Federalists came out in support, thus silencing the Anti-Federalists' most effective critique. Many Anti-Federalists, in contrast, were now opposed, realizing that Congressional approval of these amendments would greatly lessen the chances of a second constitutional convention.[72] Anti-Federalists such as Richard Henry Lee also argued that the Bill left the most objectionable portions of the Constitution, such as the federal judiciary and direct taxation, intact.[73]

Madison remained active in the progress of the amendments throughout the legislative process. Historian Gordon S. Wood writes that "there is no question that it was Madison's personal prestige and his dogged persistence that saw the amendments through the Congress. There might have been a federal Constitution without Madison but certainly no Bill of Rights."[74][75]

| Approval of the Bill of Rights in Congress and the States[76] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Seventeen Articles Approved by the House August 24, 1789 |

Twelve Articles Approved by the Senate September 9, 1789 |

Twelve Articles Approved by Congress September 25, 1789 |

Ratification Status |

| First Article: After the first enumeration, required by the first Article of the Constitution, there shall be one Representative for every thirty thousand, until the number shall amount to one hundred, after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that there shall be not less than one hundred Representatives, nor less than one Representative for every forty thousand persons, until the number of Representatives shall amount to two hundred, after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that there shall not be less than two hundred Representatives, nor less than one Representative for every fifty thousand persons. |

First Article: After the first enumeration, required by the first article of the Constitution, there shall be one Representative for every thirty thousand, until the number shall amount to one hundred; to which number one Representative shall be added for every subsequent increase of forty thousand, until the Representatives shall amount to two hundred, to which number one Representative shall be added for every subsequent increase of sixty thousand persons. |

First Article: After the first enumeration required by the first article of the Constitution, there shall be one Representative for every thirty thousand, until the number shall amount to one hundred, after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that there shall be not less than one hundred Representatives, nor less than one Representative for every forty thousand persons, until the number of Representatives shall amount to two hundred; after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that there shall not be less than two hundred Representatives, nor more than one Representative for every fifty thousand persons. |

Pending: Congressional Apportionment Amendment |

| Second Article: No law varying the compensation to the members of Congress, shall take effect, until an election of Representatives shall have intervened. |

Second Article: No law, varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives, shall take effect, until an election of Representatives shall have intervened. |

Second Article: No law, varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives, shall take effect, until an election of Representatives shall have intervened. |

Later ratified: May 5, 1992 Twenty-seventh Amendment |

| Third Article: Congress shall make no law establishing religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, nor shall the rights of Conscience be infringed. |

Third Article: Congress shall make no law establishing articles of faith, or a mode of worship, or prohibiting the free exercise of religion, or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition to the government for a redress of grievances. |

Third Article: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. |

Ratified: December 15, 1791 First Amendment |

| Fourth Article: The Freedom of Speech, and of the Press, and the right of the People peaceably to assemble, and consult for their common good, and to apply to the Government for a redress of grievances, shall not be infringed. |

(see Third Article above) | ||

| Fifth Article: A well regulated militia, composed of the body of the People, being the best security of a free State, the right of the People to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed, but no one religiously scrupulous of bearing arms, shall be compelled to render military service in person. |

Fourth Article: A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed. |

Fourth Article: A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed. |

Ratified: December 15, 1791 Second Amendment |

| Sixth Article: No soldier shall, in time of peace, be quartered in any house without the consent of the owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law. |

Fifth Article: No soldier shall, in time of peace, be quartered in any house without the consent of the owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law. |

Fifth Article: No soldier shall, in time of peace, be quartered in any house without the consent of the owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law. |

Ratified: December 15, 1791 Third Amendment |

| Seventh Article: The right of the People to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized. |

Sixth Article: The right of the People to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized. |

Sixth Article: The right of the People to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized. |

Ratified: December 15, 1791 Fourth Amendment |

| Eighth Article: No person shall be subject, except in case of impeachment, to more than one trial, or one punishment for the same offense, nor shall be compelled in any criminal case, to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation. |

Seventh Article: No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case, to be a witnesses against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation. |

Seventh Article: No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation. |

Ratified: December 15, 1791 Fifth Amendment |

| Ninth Article: In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation, to be confronted with the witnesses against him, to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defence. |

Eighth Article: In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation, to be confronted with the witnesses against him, to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favour, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defence. |

Eighth Article: In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence. |

Ratified: December 15, 1791 Sixth Amendment |

| Tenth Article: The trial of all crimes (except in cases of impeachment, and in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia when in actual service in time of War or public danger) shall be by an Impartial Jury of the Vicinage, with the requisite of unanimity for conviction, the right of challenge, and other accostomed [sic] requisites; and no person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherways [sic] infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment by a Grand Jury; but if a crime be committed in a place in the possession of an enemy, or in which an insurrection may prevail, the indictment and trial may by law be authorised in some other place within the same State. |

(see Seventh Article above) | ||

| Eleventh Article: No appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States, shall be allowed, where the value in controversy shall not amount to one thousand dollars, nor shall any fact, triable by a Jury according to the course of the common law, be otherwise re-examinable, than according to the rules of common law. |

Ninth Article: In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by Jury shall be preserved, and no fact, tried by a Jury, shall be otherwise re-examined in any court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law. |

Ninth Article: In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by Jury shall be preserved, and no fact, tried by a Jury, shall be otherwise re-examined in any court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law. |

Ratified: December 15, 1791 Seventh Amendment |

| Twelfth Article: In suits at common law, the right of trial by Jury shall be preserved. |

(see Ninth Article above) | ||

| Thirteenth Article: Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted. |

Tenth Article: Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted. |

Tenth Article: Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted. |

Ratified: December 15, 1791 Eighth Amendment |

| Fourteenth Article: No State shall infringe the right of trial by Jury in criminal cases, nor the rights of conscience, nor the freedom of speech, or of the press. |

(see Third and Ninth Articles above) | ||

| Fifteenth Article: The enumeration in the Constitution of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people. |

Eleventh Article: The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people. |

Eleventh Article: The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people. |

Ratified: December 15, 1791 Ninth Amendment |

| Sixteenth Article: The powers delegated by the Constitution to the government of the United States, shall be exercised as therein appropriated, so that the Legislative shall never exercise the powers vested in the Executive or Judicial; nor the Executive the powers vested in the Legislative or Judicial; nor the Judicial the powers vested in the Legislative or Executive. |

|||

| Seventeenth Article: The powers not delegated by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it, to the States, are reserved to the States respectively. |

Twelfth Article: The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people. |

Twelfth Article: The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people. |

Ratified: December 15, 1791 Tenth Amendment |

Ratification process

The twelve articles of amendment approved by congress were officially submitted to the Legislatures of the several States for consideration on September 28, 1789. The following states ratified some or all of the amendments:[77][78][79]

- New Jersey: Articles One and Three through Twelve on November 20, 1789, and Article Two on May 7, 1992

- Maryland: Articles One through Twelve on December 19, 1789

- North Carolina: Articles One through Twelve on December 22, 1789

- South Carolina: Articles One through Twelve on January 19, 1790

- New Hampshire: Articles One and Three through Twelve on January 25, 1790, and Article Two on March 7, 1985

- Delaware: Articles Two through Twelve on January 28, 1790

- New York: Articles One and Three through Twelve on February 24, 1790

- Pennsylvania: Articles Three through Twelve on March 10, 1790, and Article One on September 21, 1791

- Rhode Island: Articles One and Three through Twelve on June 7, 1790, and Article Two on June 10, 1993

- Vermont: Articles One through Twelve on November 3, 1791

- Virginia: Article One on November 3, 1791, and Articles Two through Twelve on December 15, 1791[80]

(After failing to ratify the 12 amendments during the 1789 legislative session.)

Having been approved by the requisite three-fourths of the several states, there being 14 States in the Union at the time (as Vermont had been admitted into the Union on March 4, 1791),[73] the ratification of Articles Three through Twelve was completed and they became Amendments 1 through 10 of the Constitution. Congress, now meeting at Congress Hall in Philadelphia, was informed of this by President Washington on January 18, 1792.[81]

As they had not yet been approved by 11 of the 14 states, the ratification of Article One (ratified by 10) and Article Two (ratified by 6) remained incomplete. The ratification plateau they needed to reach soon rose to 12 of 15 states when Kentucky joined the Union (June 1, 1792). On June 27, 1792, the Kentucky General Assembly ratified all 12 amendments, however this action did not come to light until 1996.[82]

Article One came within one state of the number needed to become adopted into the Constitution on two occasions between 1789 and 1803. Despite coming close to ratification early on, it has never received the approval of enough states to become part of the Constitution.[74] As Congress did not attach a ratification time limit to the article, it is still pending before the states. Since no state has approved it since 1792, ratification by an additional 27 states would now be necessary for the article to be adopted.

Article Two, initially ratified by seven states through 1792 (including Kentucky), was not ratified by another state for eighty years. The Ohio General Assembly ratified it on May 6, 1873 in protest of an unpopular Congressional pay raise.[83] A century later, on March 6, 1978, the Wyoming Legislature also ratified the article.[84] Gregory Watson, a University of Texas at Austin undergraduate student, started a new push for the article's ratification with a letter-writing campaign to state legislatures.[83] As a result, by May 1992, enough states had approved Article Two (38 of the 50 states in the Union) for it to become the Twenty-seventh Amendment to the United States Constitution. The amendment's adoption was certified by Archivist of the United States Don W. Wilson and subsequently affirmed by a vote of Congress on May 20, 1992.[85]

Three states did not complete action on the twelve articles of amendment when they were initially put before the states. Georgia found a Bill of Rights unnecessary and so refused to ratify. Both chambers of the Massachusetts General Court ratified a number of the amendments (the Senate adopted 10 of 12 and the House 9 of 12), but failed to reconcile their two lists or to send official notice to the Secretary of State of the ones they did agree upon.[86][73] Both houses of the Connecticut General Assembly voted to ratify Articles Three through Twelve but failed to reconcile their bills after disagreeing over whether to ratify Articles One and Two.[87] All three later ratified the Constitutional amendments originally known as Articles Three through Twelve as part of the 1939 commemoration of the Bill of Rights' sesquicentennial: Massachusetts on March 2, Georgia on March 18, and Connecticut on April 19.[73] Connecticut and Georgia would also later ratify Article Two, on May 13, 1987 and February 2, 1988 respectively.

Application and text

The Bill of Rights had little judicial impact for the first 150 years of its existence; in the words of Gordon S. Wood, "After ratification, most Americans promptly forgot about the first ten amendments to the Constitution."[88][89] The Court made no important decisions protecting free speech rights, for example, until 1931.[90] Historian Richard Labunski attributes the Bill's long legal dormancy to three factors: first, it took time for a "culture of tolerance" to develop that would support the Bill's provisions with judicial and popular will; second, the Supreme Court spent much of the 19th century focused on issues relating to intergovernmental balances of power; and third, the Bill initially only applied to the federal government, a restriction affirmed by Barron v. Baltimore (1833).[91][92][93] In the 20th century, however, most of the Bill's provisions were applied to the states via the Fourteenth Amendment—a process known as incorporation—beginning with the freedom of speech clause, in Gitlow v. New York (1925).[94] In Talton v. Mayes (1896), the Court ruled that constitutional protections, including the provisions of the Bill of Rights, do not apply to the actions of American Indian tribal governments.[95] Through the incorporation process the Supreme Court succeeded in extending to the states almost all of the protections in the Bill of Rights, as well as other, unenumerated rights.[96] The Bill of Rights thus imposes legal limits on the powers of governments and acts as an anti-majoritarian/minoritarian safeguard by providing deeply entrenched legal protection for various civil liberties and fundamental rights.[a][98][99][100] The Supreme Court for example concluded in the West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943) case that the founders intended the Bill of Rights to put some rights out of reach from majorities, ensuring that some liberties would endure beyond political majorities.[98][99][100][101] As the Court noted, the idea of the Bill of Rights "was to withdraw certain subjects from the vicissitudes of political controversy, to place them beyond the reach of majorities and officials and to establish them as legal principles to be applied by the courts."[101][102] This is why "fundamental rights may not be submitted to a vote; they depend on the outcome of no elections."[101][102]

First Amendment

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.[103]

The First Amendment prohibits the making of any law respecting an establishment of religion, impeding the free exercise of religion, abridging the freedom of speech, infringing on the freedom of the press, interfering with the right to peaceably assemble or prohibiting the petitioning for a governmental redress of grievances. Initially, the First Amendment applied only to laws enacted by Congress, and many of its provisions were interpreted more narrowly than they are today.[104]

In Everson v. Board of Education (1947), the Court drew on Thomas Jefferson's correspondence to call for "a wall of separation between church and State", though the precise boundary of this separation remains in dispute.[104] Speech rights were expanded significantly in a series of 20th- and 21st-century court decisions that protected various forms of political speech, anonymous speech, campaign financing, pornography, and school speech; these rulings also defined a series of exceptions to First Amendment protections. The Supreme Court overturned English common law precedent to increase the burden of proof for libel suits, most notably in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964).[105] Commercial speech is less protected by the First Amendment than political speech, and is therefore subject to greater regulation.[104]

The Free Press Clause protects publication of information and opinions, and applies to a wide variety of media. In Near v. Minnesota (1931)[106] and New York Times v. United States (1971),[107] the Supreme Court ruled that the First Amendment protected against prior restraint—pre-publication censorship—in almost all cases. The Petition Clause protects the right to petition all branches and agencies of government for action. In addition to the right of assembly guaranteed by this clause, the Court has also ruled that the amendment implicitly protects freedom of association.[104]

Second Amendment

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.[103]

The Second Amendment protects the individual right to keep and bear arms. The concept of such a right existed within English common law long before the enactment of the Bill of Rights.[108] First codified in the English Bill of Rights of 1689 (but there only applying to Protestants), this right was enshrined in fundamental laws of several American states during the Revolutionary era, including the 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights and the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776. Long a controversial issue in American political, legal, and social discourse, the Second Amendment has been at the heart of several Supreme Court decisions.

- In United States v. Cruikshank (1876), the Court ruled that "[t]he right to bear arms is not granted by the Constitution; neither is it in any manner dependent upon that instrument for its existence. The Second Amendment means no more than that it shall not be infringed by Congress, and has no other effect than to restrict the powers of the National Government."[109]

- In United States v. Miller (1939), the Court ruled that the amendment "[protects arms that had a] reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia".[110]

- In District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), the Court ruled that the Second Amendment "codified a pre-existing right" and that it "protects an individual right to possess a firearm unconnected with service in a militia, and to use that arm for traditionally lawful purposes, such as self-defense within the home" but also stated that "the right is not unlimited. It is not a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose".[111]

- In McDonald v. Chicago (2010),[112] the Court ruled that the Second Amendment limits state and local governments to the same extent that it limits the federal government.[113]

Third Amendment

No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.[103]

The Third Amendment restricts the quartering of soldiers in private homes, in response to Quartering Acts passed by the British parliament during the Revolutionary War. The amendment is one of the least controversial of the Constitution, and, as of February 2024, has never been the primary basis of a Supreme Court decision.[114][115][116]

Fourth Amendment

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.[103]

The Fourth Amendment guards against unreasonable searches and seizures, along with requiring any warrant to be judicially sanctioned and supported by probable cause. It was adopted as a response to the abuse of the writ of assistance, which is a type of general search warrant, in the American Revolution. Search and seizure (including arrest) must be limited in scope according to specific information supplied to the issuing court, usually by a law enforcement officer who has sworn by it. The amendment is the basis for the exclusionary rule, which mandates that evidence obtained illegally cannot be introduced into a criminal trial.[117] The amendment's interpretation has varied over time; its protections expanded under left-leaning courts such as that headed by Earl Warren and contracted under right-leaning courts such as that of William Rehnquist.[118]

Fifth Amendment

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.[103]

The Fifth Amendment protects against double jeopardy and self-incrimination and guarantees the rights to due process, grand jury screening of criminal indictments, and compensation for the seizure of private property under eminent domain. The amendment was the basis for the court's decision in Miranda v. Arizona (1966), which established that defendants must be informed of their rights to an attorney and against self-incrimination prior to interrogation by police; the Miranda warning.[119]

Sixth Amendment

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defense.[103]

The Sixth Amendment establishes a number of rights of the defendant in a criminal trial:

- to a speedy and public trial

- to trial by an impartial jury

- to be informed of criminal charges

- to confront witnesses

- to compel witnesses to appear in court

- to assistance of counsel[120]

In Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), the Court ruled that the amendment guaranteed the right to legal representation in all felony prosecutions in both state and federal courts.[120]

Seventh Amendment

In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise re-examined in any court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.[103]

The Seventh Amendment guarantees jury trials in federal civil cases that deal with claims of more than twenty dollars. It also prohibits judges from overruling findings of fact by juries in federal civil trials. In Colgrove v. Battin (1973), the Court ruled that the amendment's requirements could be fulfilled by a jury with a minimum of six members. The Seventh is one of the few parts of the Bill of Rights not to be incorporated (applied to the states).[121]

Eighth Amendment

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.[103]

The Eighth Amendment forbids the imposition of excessive bails or fines, though it leaves the term "excessive" open to interpretation.[122] The most frequently litigated clause of the amendment is the last, which forbids cruel and unusual punishment.[123][124] This clause was only occasionally applied by the Supreme Court prior to the 1970s, generally in cases dealing with means of execution. In Furman v. Georgia (1972), some members of the Court found capital punishment itself in violation of the amendment, arguing that the clause could reflect "evolving standards of decency" as public opinion changed; others found certain practices in capital trials to be unacceptably arbitrary, resulting in a majority decision that effectively halted executions in the United States for several years.[125] Executions resumed following Gregg v. Georgia (1976), which found capital punishment to be constitutional if the jury was directed by concrete sentencing guidelines.[125] The Court has also found that some poor prison conditions constitute cruel and unusual punishment, as in Estelle v. Gamble (1976) and Brown v. Plata (2011).[123]

Ninth Amendment

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.[103]

The Ninth Amendment declares that there are additional fundamental rights that exist outside the Constitution. The rights enumerated in the Constitution are not an explicit and exhaustive list of individual rights. It was rarely mentioned in Supreme Court decisions before the second half of the 20th century, when it was cited by several of the justices in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965). The Court in that case voided a statute prohibiting use of contraceptives as an infringement of the right of marital privacy.[126] This right was, in turn, the foundation upon which the Supreme Court built decisions in several landmark cases, including, Roe v. Wade (1973), which overturned a Texas law making it a crime to assist a woman to get an abortion, and Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), which invalidated a Pennsylvania law that required spousal awareness prior to obtaining an abortion.

Tenth Amendment

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.[103]

The Tenth Amendment reinforces the principles of separation of powers and federalism by providing that powers not granted to the federal government by the Constitution, nor prohibited to the states, are reserved to the states or the people. The amendment provides no new powers or rights to the states, but rather preserves their authority in all matters not specifically granted to the federal government nor explicitly forbidden to the states.[127]

Display and honoring of the Bill of Rights

George Washington had fourteen handwritten copies of the Bill of Rights made, one for Congress and one for each of the original thirteen states.[128] The copies for Georgia, Maryland, New York, and Pennsylvania went missing.[129] The New York copy is thought to have been destroyed in a fire.[130] Two unidentified copies of the missing four (thought to be the Georgia and Maryland copies) survive; one is in the National Archives, and the other is in the New York Public Library.[131][132] North Carolina's copy was stolen from the State Capitol by a Union soldier following the Civil War. In an FBI sting operation, it was recovered in 2003.[133][134] The copy retained by the First Congress has been on display (along with the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence) in the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom room at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C. since December 13, 1952.[135]

After fifty years on display, signs of deterioration in the casing were noted, while the documents themselves appeared to be well preserved.[136] Accordingly, the casing was updated and the Rotunda rededicated on September 17, 2003. In his dedicatory remarks, President George W. Bush stated, "The true [American] revolution was not to defy one earthly power, but to declare principles that stand above every earthly power—the equality of each person before God, and the responsibility of government to secure the rights of all."[137]

In 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared December 15 to be Bill of Rights Day, commemorating the 150th anniversary of the ratification of the Bill of Rights.[138] In 1991, the Virginia copy of the Bill of Rights toured the country in honor of its bicentennial, visiting the capitals of all fifty states.[139]

See also

- Anti-Federalism

- Constitutionalism in the United States

- Founding Fathers of the United States

- Four Freedoms

- Institute of Bill of Rights Law

- Patients' [bill of] rights

- Second Bill of Rights

- States' rights

- Substantive due process

- Taxpayer Bill of Rights

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom

- We Hold These Truths

Notes

- ^ In Robertson v. Baldwin, 165 U.S. 275 (1897), the United States Supreme Court stated that there are exceptions for the civil liberties and fundamental rights secured by the Bill of Rights: "The law is perfectly well settled that the first ten amendments to the Constitution, commonly known as the 'Bill of Rights,' were not intended to lay down any novel principles of government, but simply to embody certain guaranties and immunities which we had inherited from our English ancestors, and which had, from time immemorial, been subject to certain well recognized exceptions arising from the necessities of the case. In incorporating these principles into the fundamental law, there was no intention of disregarding the exceptions, which continued to be recognized as if they had been formally expressed. Thus, the freedom of speech and of the press (Article I) does not permit the publication of libels, blasphemous or indecent articles, or other publications injurious to public morals or private reputation; the right of the people to keep and bear arms (Article II) is not infringed by laws prohibiting the carrying of concealed weapons; the provision that no person shall be twice put in jeopardy (Art. V) does not prevent a second trial if upon the first trial the jury failed to agree or if the verdict was set aside upon the defendant's motion, United States v. Ball, 163 U. S. 662, 163 U. S. 627, nor does the provision of the same article that no one shall be a witness against himself impair his obligation to testify if a prosecution against him be barred by the lapse of time, a pardon, or by statutory enactment, Brown v. Walker, 161 U. S. 591, and cases cited. Nor does the provision that an accused person shall be confronted with the witnesses against him prevent the admission of dying declarations, or the depositions of witnesses who have died since the former trial."[97]

References

Citations

- ^ Bryan, Dan (April 8, 2012). "The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and its Effects". American History USA. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- ^ "Bill of Rights". history.com. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on February 25, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ England, Trent; Spalding, Matthew. "Essays on Article V: Amendments". The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on July 1, 2018. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ "Bill of Rights – Facts & Summary". History.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 8, 2015.

- ^ Rossiter, Clinton, ed. The Federalist Papers, p. 260, Federalist #45, Penguin Putnam, Inc., 1961.

- ^ Samples, John, ed. James Madison and the Future of Limited Government, p. 25, 29-30, 31, 34, Cato Institute, Washington, D.C., 2002. ISBN 1-930865-23-6.

- ^ Ketcham, Ralph. James Madison: A Biography, p. 226, American Political Biography Press, Newtown, Connecticut, 1971. ISBN 0-945707-33-9.

- ^ Ketcham, Ralph. James Madison: A Biography, p. 226, 291, American Political Biography Press, Newtown, Connecticut, 1971. ISBN 0-945707-33-9.

- ^ Samples, John, ed. James Madison and the Future of Limited Government, p. 27, 29-30, 31, 34, Cato Institute, Washington, D.C., 2002. ISBN 1-930865-23-6.

- ^ The Constitution of the United States and the Constitution of the State of California, p. 56, California Legislature Assembly, 1989.

- ^ a b c Lloyd, Gordon. "Introduction to the Constitutional Convention". Teaching American History. Archived from the original on August 16, 2013. Retrieved October 6, 2007.

- ^ Stewart, p. 47.

- ^ Beeman, p. 59.

- ^ Beeman, p. 341.

- ^ "Madison Debates, September 12". Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ^ Sherman apparently expressed the consensus of the convention. His argument was that the Constitution should not be interpreted to authorize the federal government to violate rights that the states could not violate.

Slotnick, Elliot E. (1999). Judicial Politics: Readings from Judicature. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-938870-91-3. - ^ a b Beeman, p. 343.

- ^ Rakove, p. 327.

- ^ a b Stewart, p. 226.

- ^ Rakove, p. 288.

- ^ Beeman, p. 363.

- ^ "Federal Convention, Resolution and Letter to the Continental Congress". The Founders' Constitution. The University of Chicago Press. p. 195. Archived from the original on June 7, 2013. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ^ Labunski, p. 20.

- ^ Labunski, p. 63.

- ^ "Jefferson's letter to Madison, March 15, 1789". The Founders' Constitution. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2006.

- ^ Hamilton et al., p. 436

- ^ Brutus, p. 376

- ^ Brutus, p. 377

- ^ Rakove, p. 325.

- ^ Labunski, p. 62.

- ^ Rakove, p. 323.

- ^ "On opposition to a Bill of Rights". The Founders' Constitution. University of Chicago Press. Archived from the original on January 14, 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2006.

- ^ Labunski, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Beeman, p. 388.

- ^ Beeman, pp. 389–90.

- ^ Beeman, p. 390.

- ^ a b Maier, p. 431.

- ^ Labunksi, pp. 113–15

- ^ a b Brookhiser, p. 80.

- ^ Maier, p. 430.

- ^ Maier, p. 429.

- ^ "From Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, 20 December 1787". founders.archives.gov. United States National Archives and Records Administration. December 20, 1787. Archived from the original on January 30, 2023. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

- ^ Maier, p. 433.

- ^ Brookhiser, p. 76.

- ^ Labunski, pp. 159, 174.

- ^ Labunski, p. 161.

- ^ Labunski, p. 162.

- ^ Brookhiser, p. 77.

- ^ Labunski, p. 192.

- ^ Labunski, p. 188.

- ^ Gordon Lloyd. "Anticipating the Bill of Rights in the First Congress". TeachingAmericanHistory.org. Ashland, Ohio: The Ashbrook Center at Ashland University. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ a b Labunski, p. 198.

- ^ Labunski, p. 199.

- ^ a b Madison introduced "amendments culled mainly from state constitutions and state ratifying convention proposals, especially Virginia's." Levy, p. 35

- ^ "Virginia Declaration of Rights: Primary Documents of American History (Virtual Programs & Services, Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- ^ Ellis, p. 210.

- ^ Ellis, p. 212.

- ^ Lloyd, Gordon Lloyd. "Madison's Speech Proposing Amendments to the Constitution: June 8, 1789". 50 Core Documents That Tell America's Story, teachingamericanhistory.org. Ashland, Ohio: Ashbrook Center at Ashland University. Archived from the original on August 9, 2018. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ^ Labunski, pp. 203–205.

- ^ Labunski, p. 215.

- ^ Labunski, p. 201.

- ^ Brookhiser, p. 81.

- ^ Labunski, p. 217.

- ^ Labunski, pp. 218–220.

- ^ Ellis, p. 207.

- ^ Labunski, p. 235.

- ^ Labunski, p. 237.

- ^ Labunski, p. 221.

- ^ Adamson, Barry (2008). Freedom of Religion, the First Amendment, and the Supreme Court: How the Court Flunked History. Pelican Publishing. p. 93. ISBN 9781455604586. Archived from the original on May 11, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2015 – via Google Books.

- ^ Graham, John Remington (2009). Free, Sovereign, and Independent States: The Intended Meaning of the American Constitution. Foreword by Laura Tesh. Arcadia. Footnote 54, pp. 193–94. ISBN 9781455604579. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2015 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Creating the United States - Creating the Bill of Rights". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ^ Wood, p. 71.

- ^ a b c d Levy, Leonard W. (1986). "Bill of Rights (United States)". Encyclopedia of the American Constitution. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ a b Wood, p. 69.

- ^ Ellis, p. 206.

- ^ Gordon Lloyd. "The Four Stages of Approval of the Bill of Rights in Congress and the States". TeachingAmericanHistory.org. Ashland, Ohio: The Ashbrook Center at Ashland University. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ "The Constitution of the United States of America: Analysis and Interpretation, Centennial Edition, Interim Edition: Analysis of Cases Decided by the Supreme Court of the United States to June 26, 2013" (PDF). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. 2013. p. 25. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 25, 2014. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- ^ James J. Kilpatrick, ed. (1961). The Constitution of the United States and Amendments Thereto. Virginia Commission on Constitutional Government. p. 64.

- ^ Wonning, Paul R. (2012). A Short History of the United States Constitution: The Story of the Constitution the Bill of Rights and the Amendments. Mossy Feet Books. pp. 27–28. ISBN 9781310451584. Archived from the original on December 9, 2016. Retrieved September 7, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Ratifications of the Amendments to the Constitution of the United States | Teaching American History". teachingamericanhistory.org. Archived from the original on September 18, 2016. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ "Founders Online: From George Washington to the United States Senate and House o ..." Archived from the original on March 13, 2018. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- ^ Kyvig, pp. 464–467.

- ^ a b Dean, John W. (September 27, 2002). "The Telling Tale of the Twenty-Seventh Amendment". FindLaw. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ Bernstein, Richard B. (1992). "The Sleeper Wakes: The History and Legacy of the Twenty-Seventh Amendment". Fordham Law Review. 61 (3): 537. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ Bernstein, Richard B. (2000). "Twenty-Seventh Amendment". Encyclopedia of the American Constitution. Archived from the original on September 19, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ Kaminski, John P.; Saladino, Gaspare J.; Leffler, Richard; Schoenleber, Charles H.; Hogan, Margaret A. "The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution, Digital Edition" (PDF). Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2015. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ Kyvig, p. 108.

- ^ Wood, p. 72.

- ^ "The Bill of Rights: A Brief History". ACLU. Archived from the original on August 30, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Labunski, p. 258.

- ^ Labunski, pp. 258–259.

- ^ "Barron v. Mayor & City Council of Baltimore – 32 U.S. 243 (1833)". Justia.com. Archived from the original on May 21, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ Levy, Leonard W. (January 1, 2000). "BARRON v. CITY OF BALTIMORE 7 Peters 243 (1833)". Encyclopedia of the American Constitution. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ Labunski, p. 259.

- ^ Deloria, Vine Jr. (2000). "American Indians and the Constitution". Encyclopedia of the American Constitution. Archived from the original on September 19, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ Drexler, Ken. "Research Guides: 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Primary Documents in American History: Introduction". guides.loc.gov. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- ^ Robertson, at 281-282.

- ^ a b Jeffrey Jowell and Jonathan Cooper (2002). Understanding Human Rights Principles. Oxford and Portland, Oregon: Hart Publishing. p. 180. ISBN 9781847313157. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ a b Loveland, Ian (2002). "Chapter 18 – Human Rights I: Traditional Perspectives". Constitutional Law, Administrative Law, and Human Rights: A Critical Introduction (Seventh ed.). London: Oxford University Press. p. 559. ISBN 9780198709039. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ a b Jayawickrama, Nihal (2002). The Judicial Application of Human Rights Law: National, Regional and International Jurisprudence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 98. ISBN 9780521780421. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ a b c West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624, Majority Opinion, item 3 (US 1943) (""The very purpose of a Bill of Rights was to withdraw certain subjects from the vicissitudes of political controversy, to place them beyond the reach of majorities and officials and to establish them as legal principles to be applied by the courts. One's right to life, liberty, and property, to free speech, a free press, freedom of worship and assembly, and other fundamental rights may not be submitted to vote; they depend on the outcome of no elections.""), archived from the original.

- ^ a b Obergefell v. Hodges, No. 14-556, slip op. Archived April 12, 2019, at the Wayback Machine at 24 (U.S. June 26, 2015).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Bill of Rights Transcript". Archives.gov. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved May 15, 2010.