True History: An Account of Cannibal Captivity in Brazil

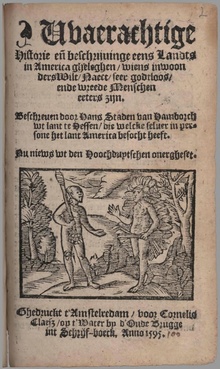

Title page of the 1595 Dutch Edition | |

| Author | Hans Staden |

|---|---|

| Original title | Warhaftige Historia und beschreibung eyner Landtschafft der Wilden Nacketen, Grimmigen Menschfresser-Leuthen in der Newenwelt America gelegen |

| Language | German |

| Publisher | Andreas Kolbe |

Publication date | 1557 |

| Publication place | Germany |

True History: An Account of Cannibal Captivity in Brazil (German: Warhaftige Historia und beschreibung eyner Landtschafft der Wilden Nacketen, Grimmigen Menschfresser-Leuthen in der Newenwelt America gelegen) is an account published by the German soldier Hans Staden in 1557 describing his two trips to the new world. The book is best known for Staden's descriptions of his experiences while held captive by the Tupinambá near Bertioga, Brazil.[1] True History became one of the best-selling travel narratives of the sixteenth century.[2]

Hans Staden arrived in Brazil as a gunner for the Portuguese in 1550 and was taken as a prisoner of war by the Tupinambá people of Brazil. The Tupinambá were reputed to perform cannibalistic rituals, especially with prisoners of war. Since the Tupinambá were French allies and the French and Portuguese were enemies, the account was a dramatic first person account from a Portuguese view of the natives.

Historical Context

During Staden's adventures, an imperial confrontation was taking place between the French, the Spanish and the Portuguese, whose naval power was unmatched at the time. They contended for resources and control of global trading, which often resulted in violence.[3] Due to Brazil's position as a top-priority resource, violence there was common.

Native tribes were forced to form alliances with western powers to survive. One tribe, known as the Tupiniquin, allied with the Portuguese; another, called the Tupinambá, allied with the French.[3] As a mercenary, Staden fought for both Portugal and France, eventually finding himself as part of a garrison in a Portuguese settlement, which led to his being captured by the Tupinambá. Staden's experience was one of the first accounts of cannibalism by a European, and later caused turmoil in the world of anthropology, which had previously disputed the existence of cannibalism.[3]

Background

Hans Staden was a German traveler born around 1520 in Hesse, a principality of the Holy Roman Empire. He studied in several towns in Hesse and even served as a soldier. In 1547, Staden declared that he would be leaving Hesse for India. He soon found himself in Latin America.

Staden was known as a “go-between,” a mediator of sorts between the Europeans and the indigenous tribes. In addition to mediation, he also acted as a broker and translator for the Europeans. He was a mediator in multiple respects: social, economic and trade. Like any other “go-between,” he did not take sides.

It was after Staden’s capture by the Tupinambá that he became a mediator. He possessed abundant knowledge of the land, geography and people, and during his time as a captive he made a conscious effort to learn the Tupinambá language, beliefs and customs.

Once Staden gained this abundant knowledge of Tupinambá, they became pawns in his game. He began to deceive them. He claimed that the tribe’s oracles and gourds, known as Tamaraka, were lying about him. He changed his self-image in order to make his captors fear him. While achieving his own ends, he also made offers to be their healer, mercenary and even prophet.

In 1552, after being released by Charles V, Staden returned home to Hesse, where he remained until his death in 1579. Allegedly, in 1556, he even spoke to a prince, Landgrave Phillip about his book. Staden described it as an adventure story, much more leisurely than the actual events.[4][clarification needed]

Synopsis

True History: An Account of Cannibal Captivity in Brazil recounts various observations Hans Staden, a German explorer, had of a tribal group in Brazil called Tupinambá. This travel log consists of two introductions, a list of illustrations, and a two-part narrative, with fifty-three chapters and thirty-six chapters, respectively. Staden introduces cannibalism as a cultural and religious practice alongside his survival journey. He shares his personal views on the indigenous culture, traditions, and lifestyle from the perspective of a European captive.

Staden’s experience begins with his capture by two Tupinambá males—Jeppipo Wasu and Alkindar Miri—who took him to a small village called Uwattibi [Ubatuba].[5] He initially felt fear because they desired to eat his flesh. Religious rituals such as singing, dancing, and worship that suggested cannibalistic intentions compounded his fear.[5] Ipperu Wasu, who held Staden as a captive, gave Staden to Alkindar Miri in return of a favor. Staden believed his death would involve barbaric methods, as he underwent a series of rites. The Tupinambá people decorated him with strings and rings, and further continued to dance as a form of ritual.[5]

The Tupinambá distrusted the Portuguese, favoring the French, who established diplomatic relations through trade. The Tupinambá people categorized Staden as Portuguese, which put his life at risk.[5] The two natives who captured Staden harbored hostility against the Portuguese, who had slain their father. Their desire for revenge promised to ensure Staden’s fate. Despite Staden’s attempt to convince the Tupinambá by lying about his nationality, a Frenchman disproved Staden’s claim to be French.[5] Staden believed the Frenchman would support him, based on their mutual religious background. Instead, the Frenchman sided with the Tupinambá and departed as soon as he had his load ready.[5]

After several days' imprisonment, the Tupinambá transported Staden to another village, called Arirab [Ariro], where he met their highest king, Konyan Bebe. During his visit, Staden continued to persuade the king that he was not an enemy.[5] He flattered the king by noting his fierce and belligerent personality, while the king proceeded in questioning Staden’s nationality as well as sharing stories of how he had slain the Portuguese.[5] After his interrogation, the Tupinambá brought Staden back to Uwattibi. Staden expected to be killed upon arrival.[5] However, the Tupiniquins attacked the village, during which time Staden volunteered to assist the Tupinambá in combat. Despite his display of fealty, Staden again was placed under surveillance.[5]

In Part II, Staden shares his observations on the Tupinambá nature, culture, and lifestyle. His perception of South America was dominated by the rich forest and mountains.[5] He describes the indigenous people as savages who were naked, dark skinned, dextrous, and had facial paintings.[5] He notes that the dwellings were well protected from enemies, with resources such as food and wood located within their huts.[5] Staden notes the technology devised by the indigenous people. He recounts how the natives created fire through using friction, which later plays a crucial role in manufacturing cooking utensils such as pots.[5] In regions with no European presence, the natives use animal tools[clarification needed] to cut and hew, as they are unaware of axes, knives, and scissors.[5] Some European influence was scattered across the indigenous population. Staden mentions that a few tribal groups who participated in trade with the Europeans consumed salt, whereas those who did not do so ate no salt.[5] He mentions boiling as an essential part of the culinary culture.[5] The indigenous hunting techniques that involved using tools such as bows, arrows, and nets served as a huge contributor to the food supply.[5] Staden states “It seldom happens that a man returns empty-handed from hunting.”[5] Although Staden notes the indigenous communities “do not have any particular form of government or law,”[5] he notes that chiefs were integral political figures who tended to show competency in waging war and that social hierarchy existed in indigenous societies.[5]

Reception

His book was a success in 16th century Europe, and one of the most popular travel narratives of its time,[6] specially due to its descriptive nature, its illustrations and religious message.[7] The popularity of the work meant that it shaped the European imagination about Brazil during the first centuries of its colonization, helping to create both a paradisiacal vision of the New World and a demonic one when necessary.[8]

Many critics agree that Staden’s account is a unique source of information on indigenous cultures.[9][10][11][12] Some modern critics have argued that Staden's account is one of the most reliable of its kind because he spent a long time in Brazil and spoke indigenous languages.[13]

Depending on the edition, some critics take issue with the editors’ interpretation and introduction.[14] Some modern critics argue that Staden exaggerated accounts of cannibalism and even fabricated parts of his story based on similar narratives written by others.[15] Santana-Dezmann 2019 states that Staden helped to create an "irreal view" with prejudices and stereotypes about Brazil and its people, in a time which the country of Brazil and the Brazilian people didn't exist, and in a region that was still in its colonial period.[16]

The book has been translated into several languages,[a] received several adaptations at least since 1625,[18] and[19] has also been interpreted through several political and social movements according to their agendas. The interpretations include a “children’s book … Antropofagia [Cannibalism] … Estado Novo … Cinema Novo … neo-nationalist and postmodern commemoration … [and] a forgettable and tedious movie.”[20]

The Brazilian writer Monteiro Lobato deconstructed the portrait of Hans Staden as a “good European” in his adaptation of the work in the Sítio do Picapau Amarelo children's books series, showing that his survival was due to cowardice, not any "heroic traits".[21] Santana-Dezmann 2019 explains that under the indigenous beliefs, Staden's flesh carried his cowardice, so that's why he managed to stay alive.[22]

Selected editions

- Staden, Hans (1557). Warhaftige Historia und beschreibung eyner Landtschafft der Wilden Nacketen, Grimmigen Menschfresser-Leuthen in der Newenwelt America gelegen. Marpurg: Kolb. Original German edition, 1557.

- Staden, Hans (1874). The Captivity of Hans Stade of Hesse, in A.D. 1547-1555, Among the Wild Tribes of Eastern Brazil. Translated by Albert Tootal. annotated by Richard F. Burton. The Hakluyt Society. English translation by the Hakluyt Society, 1874.

- Staden, Hans (2008). Hans Staden's True History: An Account of Cannibal Captivity in Brazil. Translated by Neil L. Whitehead; Michael Harbsmeier. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4231-1. New English translation, 2008.

References

- ^ Whitehead, Neil L. (2000). "Hans Staden and the Cultural Politics of Cannibalism". Hispanic American Historical Review. 80 (4): 721–751. doi:10.1215/00182168-80-4-721. S2CID 145167648.

- ^ Häberlein, M. (2005). "Hans Staden". In Adam, Thomas (ed.). Germany and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

- ^ a b c Fritze, Ronald H. (2010). "Reviewed work: Hans Staden's "True History": An Account of Cannibal Captivity in Brazil. The Cultures and Practice of Violence, Michael Harbsmeier, Neil L. Whitehead". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 41 (2): 557–558. doi:10.1086/SCJ27867848. JSTOR 27867848.

- ^ Duffy, Eve M., and Alida C. Metcalf. The return of Hans Staden: a go-between in the Atlantic world. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Staden, Hans (2008). Hans Staden's True History: An Account of Cannibal Captivity in Brazil. Duke University Press. p. 117.

- ^ Häberlein, Mark. "Germany and the Americas: culture, politics and history".

- ^ Santana-Dezmann 2019, p. 60.

- ^ Santana-Dezmann 2019, p. 59.

- ^ Brotherston, Gordon (December 2009). "Reviewed Work(s): Hans Staden's True History: An Account of Cannibal Captivity in Brazil by Hans Staden, Neil L. Whitehead and Michael Harbsmeier". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 15 (4): 869–870. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2009.01589_12.x. JSTOR 40541770.

- ^ Jáuregui, Carlos A. (2010). "Reviewed Work(s): Hans Staden's True History: An Account of Cannibal Captivity in Brazil. [Warhafiige Historia und Beschreibung eyner Landtschafft der wilden, nacketen, grimmigen Menschfresser Leuthen in der Newenwelt America gelegen (1557)] by Hans Staden, Neil L. Whitehead and Michael Harbsmeier". Luso-Brazilian Review. 47 (1): 219–223. doi:10.1353/lbr.0.0102. JSTOR 40985181. S2CID 144486873.

- ^ Wright, Robin M. (Spring 2010). "Reviewed Work(s): Hans Staden's True History: An Account of Cannibal Captivity in Brazil by Hans Staden, Neil L. Whitehead and Michael Harbsmeier". Journal of Anthropological Research. 66 (1): 134–135. doi:10.1086/jar.66.1.27820857. JSTOR 27820857.

- ^ L.E.J. (March 1929). "Hans Staden: The True History of His Captivity, 1557 by Malcolm Letts". The Geographical Journal. 73 (3): 292. doi:10.2307/1784738. JSTOR 1784738.

- ^ Bieber, Judy (September 2011). "Hans Staden's True History: An Account of Cannibal Captivity in Brazil - By Hans Staden". Historian. 73 (3). College of Wooster Libraries: 585–587. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.2011.00301_29.x. S2CID 142966782.

- ^ Jáuregui, Carlos A. "Reviewed Work(s): Hans Staden's True History: An Account of Cannibal Captivity in Brazil. [Warhafiige Historia und Beschreibung eyner Landtschafft der wilden, nacketen, grimmigen Menschfresser Leuthen in der Newenwelt America gelegen (1557)] by Hans Staden, Neil L. Whitehead and Michael Harbsmeier". Luso-Brazilian.

- ^ Schmölz-Häberlein, Michaela. "Hans Staden, Neil L. Whitehead, and the Cultural Politics of Scholarly Publishing". Hispanic American Historical Review.

- ^ Santana-Dezmann 2019, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Santana-Dezmann 2019, pp. 113–115, Anexo II.

- ^ Santana-Dezmann 2019, p. 76.

- ^ L.E.J. (March 1929). "Hans Staden: The True History of His Captivity, 1557 by Malcolm Letts". The Geographical Journal. 73 (3): 292. doi:10.2307/1784738. JSTOR 1784738.

- ^ Jáuregui, Carlos A. (2010). "Reviewed Work(s): Hans Staden's True History: An Account of Cannibal Captivity in Brazil. [Warhafiige Historia und Beschreibung eyner Landtschafft der wilden, nacketen, grimmigen Menschfresser Leuthen in der Newenwelt America gelegen (1557)] by Hans Staden, Neil L. Whitehead and Michael Harbsmeier". Luso-Brazilian Review. 47 (1): 219–223. doi:10.1353/lbr.0.0102. JSTOR 40985181. S2CID 144486873.

- ^ Santana-Dezmann 2019, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Santana-Dezmann 2019, p. 68.

Note

- ^ Santana-Dezmann 2019, lists that the book was translated in 8 languages across 50 editions between 1557-1942.[17]

Additional reading

- Santana-Dezmann, Vanete (2019). Hy Brasil: a construção de uma nação (in Brazilian Portuguese) (1 ed.). Maringá: Viseu. p. 115. ISBN 978-8530009403. OCLC 1353609067.