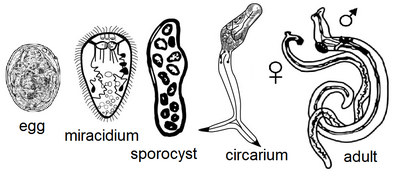

Trematode life cycle stages

Trematodes are parasitic flatworms of the class Trematoda, specifically parasitic flukes with two suckers: one ventral and the other oral. Trematodes are covered by a tegument, that protects the organism from the environment by providing secretory and absorptive functions.

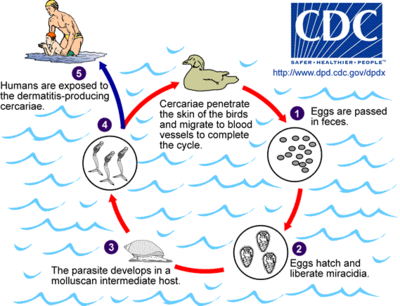

The life cycle of a typical trematode begins with an egg. Some trematode eggs hatch directly in the environment (water), while others are eaten and hatched within a host, typically a mollusc. The hatchling is called a miracidium, a free-swimming, ciliated larva. Miracidia will then grow and develop within the intermediate host into a sac-like structure known as a sporocyst or into rediae, either of which may give rise to free-swimming, motile cercariae larvae. The cercariae then could either infect a vertebrate host or a second intermediate host. Adult metacercariae or mesocercariae, depending on the individual trematode's life cycle, will then infect the vertebrate host or be rejected and excreted through the rejected host's faeces or urine.[1]

Typical life cycle stages

While the details vary with each species, the general life cycle stages are:

Egg

The egg is found in the faeces, sputum, or urine of the definitive host. Depending on the species, it will either be non-embryonated (immature) or embryonated (ready to hatch). The eggs of all trematodes (except schistosomes) are operculated. Some eggs are eaten by the intermediate host (snail) or they are hatched in their habitat (water).

Miracidium

Miracidia hatch from eggs either in the environment or in the intermediate host. They do not have a mouth; therefore they cannot eat and need to find a host quickly if they hatch in the environment. Energy is needed to develop into a sporocyst. The first intermediate host can differ for different trematodes.[3]

Sporocyst

Sporocysts are elongated sacs that produce either more sporocysts or rediae. This is where larvae can develop.[4]

- Mother sporocyst: These have loose plates (cilia) and migrate to gonads.

- Daughter sporocyst: These are an asexual production of cercariae; they absorb nutrients while having no mouth.

Redia (plural: rediae)

After the sporocyst the larva forms. The first development from it forms the redia.[5] They have a mouth which allows them to have an advantage to their competitors because they can just consume them and will either produce more rediae or start to form cercariae.

Parasite competition in snail hosts

Co-infections of different parasite species within the same host could occur and cause competition between the rediae and sporocysts. Not all trematode species have a redia stage; some may just have a sporocyst stage depending on the life cycle. The rediae are dominant over sporocysts because they have mouths and are able to either eat their competitors' food or their competitors.[citation needed]

Cercaria (plural: cercariae)

The larval form of the parasite develops within the germinal cells of the sporocyst or redia.[6] A cercaria has a tapering head with large penetration glands.[7] It may or may not have a long swimming "tail", depending on the species.[6] The motile cercaria finds and settles in a host where it will become either an adult, a mesocercaria, or a metacercaria, according to species.

- Mesocercaria: They are involved in an encysted stage either on vegetation or in a host tissue on the second intermediate host. They have a hard shell and are also involved in the trophic transmission. This is where the parasite is able to infect the definitive host because it consumes the second intermediate host that has metacercariae on/in it.[citation needed]

- Metacercaria: A cercaria encysted and resting. They are only involved when there are three intermediate host life cycles.[citation needed]

Species of family Syncoeliidae have mesocercariae or metacercariae that are not encysted and can be free floating, but details of the early stages of the life cycles of these marine parasites are not known.[8]: 228–234 Bony and cartilaginous fish are the definitive hosts within at least the gills, oral cavity or skin, and crustaceans like krill and copepods can be paratenic or possibly intermediate hosts.[9]: 32–33 Metacercariae of certain species, such as Copiatestes filiferum, have long filamentous structures termed byssal filaments,[10][11] which in C. filiferum have been reported to foul the feet of white-faced storm petrels and cause snagging-related mortality in this accidental host after the metacercariae dry out and form hardened connections between the legs.[12]

Cercaria is also used as a genus of trematodes, when adult forms are not known.[13] The usage dates back to Müller, in 1773.[14]

Adult

The fully developed mature stage. As an adult, it is capable of sexual reproduction.

Deviations from the typical life cycle

Not all trematodes follow the typical sequence of eggs, miracidia, sporocysts, rediae, cercariae, and adults. In some species, the redial stage is omitted, and sporocysts produce cercariae. In other species, the cercaria develops into an adult within the same host.

Many digenean trematodes require two hosts; one (typically a snail) where asexual reproduction occurs in sporocysts, the other a vertebrate (typically a fish) where the adult form engages in sexual reproduction to produce eggs. In some species (for example Ribeiroia) the cercaria encysts, waits until their host is eaten by a third host, in whose gut it emerges and develops into an adult.

Most trematodes are hermaphroditic, but members of the family Schistosomatidae are dioecious. Males are shorter and stouter than the females.[7]

Representations of life cycles of several different trematode species

See also

References

- ^ Poulin, Robert; Cribb, Thomas H (2002). "Trematode life cycles: Short is sweet?". Trends in Parasitology. 18 (4): 176–83. doi:10.1016/S1471-4922(02)02262-6. PMID 11998706.

- ^ Caffara, Monica; Davidovich, Nadav; Falk, Rama; Smirnov, Margarita; Ofek, Tamir; Cummings, David; Gustinelli, Andrea; Fioravanti, Maria L (2014). "Redescription of Clinostomum phalacrocoracis metacercariae (Digenea: Clinostomidae) in cichlids from Lake Kinneret, Israel". Parasite. 21: 32. doi:10.1051/parasite/2014034. PMC 4078730. PMID 24986336.

- ^ Galaktionov, K. V., & Dobrovolʹskiĭ, A. A. (2003). The biology and evolution of trematodes: An essay on the biology, morphology, life cycles, transmission, and evolution of digenetic trematodes. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.[page needed]

- ^ Fried, Bernard, and Thaddeus K. Graczyk. Echinostomes as Experimental Models for Biological Research. Springer, 2011.[page needed]

- ^ Fried, Bernard, and Thaddeus K. Graczyk. Echinostomes as Experimental Models for Biological Research. Springer, 2011.[page needed]

- ^ a b "Glossary". VPTH 603 Veterinary Parasitology. University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ a b "Schistosoma". Australian Society for Parasitology. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ Gibson, David I.; Bray, Rodney A. (1977). "The Azygiidae, Hirudinellidae, Ptychogonimidae, Sclerodistomidae and Syncoeliidae (Digenea) of fishes from the northeast Atlantic". Bulletin of the British Museum of Natural History. 32 (6): 167–245.

- ^ Morales-Ávila, José Raúl; Gomez-Gutierrez, Jaime; Gómez del Prado-Rosas, María del Carmen; Robinson, Carlos J. (2015). Klimpel, Sven (ed.). "Larval trematodes Paronatrema mantae and Copiatestes sp. parasitize Gulf of California krill (Nyctiphanes simplex, Nematoscelis difficilis)". Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 116 (1): 23–35. doi:10.3354/dao02901. PMID 26378405.

- ^ Overstreet, Robin M. (1970). "A Syncoeliid (Hemiuroidea Faust, 1929) Metacercaria on a Copepod from the Atlantic Equatorial Current". The Journal of Parasitology. 56 (4): 834–836. doi:10.2307/3277733.

- ^ Gibson, David; Appeltans, Ward. "Copiatestes filiferus (Leuckart in Sars, 1885) Gibson & Bray, 1977". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ Claugher, D. (1976). "A trematode associated with the death of the white-faced storm petrel (Pelagodroma marina) on the Chatham Islands". Journal of Natural History. 10 (6): 633–641. Bibcode:1976JNatH..10..633C. doi:10.1080/00222937600770501.

- ^ Cercaria at WoRMS

- ^ Vermium terrestrium et fluviatile seu animalium infusorium, helminthicorum et testaceorum, non marinorum, succinct historia. OF Müller, 1773

External links