Convention of Pardo

El Pardo Palace | |

| Context | Agree compensation for commercial claims; Commission to establish boundaries between Spanish Florida and Georgia |

|---|---|

| Signed | 14 January 1739 |

| Location | Royal Palace of El Pardo, Madrid |

| Effective | Not ratified |

| Signatories | |

| Parties | |

The Convention of Pardo, also known as the Treaty of Pardo or Convention of El Pardo, was a 1739 agreement between Britain and Spain. It sought to resolve trade issues between the two countries and agree boundaries between Spanish Florida and the English colony of Georgia.

The Convention established a Boundary Commission to set borders between Georgia and Florida, while Spain provided compensation of £95,000 for confiscated British property. In return, the British South Sea Company would pay £68,000 to settle Spanish claims for profits due on the Asiento de Negros.

Despite being owned by the British government, it refused to do so; both countries rejected the Convention, leading to the outbreak of the War of Jenkins' Ear on 23 October 1739.

Background

In the 18th century, wars were often fought over commercial issues, due to the then dominant economic theory of mercantilism. This viewed trade as a finite resource, so if one country increased its share, it must be at the expense of others.[1]

The 1713 Treaty of Utrecht ending the War of the Spanish Succession included commercial provisions allowing Britain to trade directly with New Spain. They included the Asiento de Negros, a monopoly to supply 5,000 slaves a year to its colonies in the Americas and the Navio de Permiso, permitting British ships to sell 1,000 tons of goods in Porto Bello and Veracruz.[2] However, these turned out to be relatively unprofitable and have been described as a 'commercial illusion'; between 1717 and 1733, the British sent only eight ships to the Americas.[3]

The real profits came from smuggled goods that evaded customs duties, with demand from Spanish colonists creating a large black market.[4] Accepting it could not be stopped, the Spanish authorities used it as an informal instrument of policy. During the 1727 to 1729 Anglo-Spanish War, French ships carrying contraband were let through, while British ships were stopped.[5]

The British accepted the occasional confiscation of ships and goods as part of the cost of business but were concerned by the prospect of being replaced by the French.[6] These were heightened by the 1733 Pacte de Famille between Louis XV and his uncle Philip V, indicating greater alignment between France and Spain.[7]

The 1729 Treaty of Seville allowed the Spanish to board British vessels trading with New Spain; in 1731, Robert Jenkins, captain of the Rebecca, claimed a coast guard officer severed his ear. The legend this was later exhibited to the House of Commons has no basis in fact and the incident forgotten with the easing of restrictions in 1732.[8]

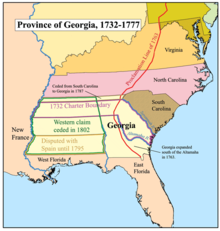

The establishment of the British colony of Georgia in early 1733 increased tension, since it appeared to threaten Spanish Florida, vital for protecting trade between mainland Spain and its colonies.[9] A second round of 'depredations' in 1738 led to demands for compensation, British newsletters and pamphlets presenting them as inspired by France.[10] This placed political pressure on Robert Walpole, the long-serving British Prime Minister, to reach a satisfactory deal.

Negotiations

Delegates from both sides met at the El Pardo palace in Madrid from late 1738. By January 1739, they had drawn up a basic agreement. The British had initially demanded £200,000 in compensation but ultimately accepted just £95,000. Spain originally demanded unlimited rights to search vessels, but this was eventually restricted to those in Spanish waters.

In return, the British South Sea Company would pay Philip V of Spain £68,000 to settle his share of proceeds from the Asiento de Negros and a Boundary Commission established to settle borders between Georgia and Florida. The chief British negotiator Sir Benjamin Keene felt this was a good deal and signed on 14 January.

Aftermath

The Convention was extremely unpopular in London. Many merchant captains were unhappy that the British compensation claim had been more than halved, the South Sea Company being concerned by the agreement allowing the Spanish limited rights to search British ships. Within months, the situation had turned sharply towards war, and the Convention grew increasingly fragile. Opponents published a list of all those who voted in favour of the Convention, including details of their income from government positions.[11]

When the South Sea Company refused to pay the agreed £68,000, Philip V rescinded the asiento de Negros. On 20 July 1739, the Admiralty sent a naval force under Admiral Vernon to the West Indies, reaching Antigua in early October. Three British ships attacked La Guaira, principal port of the Province of Venezuela on 22 October; Britain formally declared war the next day, beginning the War of Jenkins' Ear.[12]

Sir Benjamin Keene was closely associated with Walpole and after his fall, there was some discussion of impeaching him for negotiating the Convention. The war later become submerged into the wider War of the Austrian Succession. The issues that had started the war were largely ignored during the Congress of Breda and the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle that ended it in 1748, as they were no longer priorities for the two sides.

Some issues were eventually resolved in the 1750 Treaty of Madrid, but illegal British trade with the Spanish colonies continued to flourish. The Spanish Empire in the Caribbean remained intact and victorious despite several English attempts to seize some of its heavily defended and fortified colonies. Spain would later use its trading routes and resources to help the rebels' cause in the American Revolution.

The issue resurfaced in the dispute between the United States and Spain known as the West Florida Controversy; it was initially resolved by Pinckney's Treaty in 1796, then settled when Spanish Florida was relinquished in the 1819 Adams-Onis Treaty.

References

- ^ Rothbard, Murray (23 April 2010). "Mercantilism as the Economic Side of Absolutism". Mises.org. Good summary of the concept. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ Browning 1993, p. 21.

- ^ Anderson 1976, p. 293.

- ^ Richmond 1920, p. 2.

- ^ Mclachlan 1940, pp. 91–93.

- ^ Woodfine 1998, p. 92.

- ^ McKay 1983, pp. 138–140.

- ^ Harbron 1998, p. 3.

- ^ Ibañez 2008, p. 18.

- ^ Mclachlan 1940, pp. 94.

- ^ The History and Proceedings of the House of Commons: 1740. Houses of Parliament. 1742. pp. 469–472.

- ^ Rodger 2005, p. 238.

Sources

- Anderson, MS (1976). Europe in the Eighteenth Century, 1713-1783 : (A General History of Europe). Longman. ISBN 978-0582486720.

- Browning, Reed (1975). The Duke of Newcastle. Yale University. ISBN 9780300017465.

- Browning, Reed (1993). The War of the Austrian Succession. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0312094836.

- Harbron, John (1998). Trafalgar and the Spanish Navy: The Spanish Experience of Sea Power. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0870216954.

- Ibañez, Ignacio Rivas (2008). Mobilizing Resources for War: The Intelligence Systems during the War of Jenkins' Ear. PHD UCL.

- McKay, Derek (1983). The rise of the great powers, 1648-1815. London: Longman. ISBN 978-0582485549.

- Mclachlan, Jean O (1940). Trade and Peace with Old Spain (2015 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107585614.

- Richmond, Herbert (1920). The Navy in the War of 1739-48 - War College Series (2015 ed.). War College Series. ISBN 978-1296326296.

- Rodger, NAM (2005). The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649-1815. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393060508.

- Simms, Brendan. Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire. Penguin Books, 2008.

- Woodfine, Philip (1998). Britannia's Glories: The Walpole Ministry and the 1739 War with Spain. Royal Historical Society. ISBN 978-0861932306.