Treaty of Constantinople (1590)

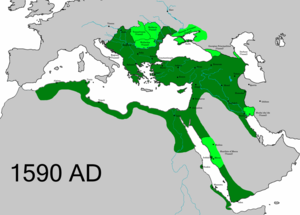

The Treaty of Constantinople, also known as the Peace of Istanbul[1][2] or the Treaty of Ferhad Pasha[3] (Turkish: Ferhat Paşa Antlaşması), was a treaty between the Ottoman Empire and the Safavid Empire ending the Ottoman–Safavid War of 1578–1590. It was signed on 21 March 1590 in Constantinople (present-day Istanbul). The war started when the Ottomans, then ruled by Murad III, invaded the Safavid possessions in Georgia, during a period of Safavid weakness.[4] With the empire beleaguered on numerous fronts and its domestic control plagued by civil wars and court intrigues, the new Safavid king Abbas I, who had been placed on the throne in 1588, opted for unconditional peace, which led to the treaty. The treaty put an end to 12 years of hostilities between the two arch rivals.[1] While both the war and the treaty were a success for the Ottomans, and severely disadvantageous for the Safavids, the new status quo proved to be short lived, as in the next bout of hostilities, several years later, all Safavid losses were recovered.

War

At the time the war commenced, the Safavid Empire was in a chaotic state under its weak ruler, Mohammad Khodabanda. In the resulting fighting, the Ottomans had managed to take most of the Safavid provinces of Azerbaijan (including the former capital Tabriz), Georgia (Kartli, Kakheti, eastern Samtskhe-Meskheti), Karabagh, Erivan, Shirvan and Khuzestan,[1] despite Mohammad Khodabanda's initially successful counterattack.[3][5] When Abbas I succeeded to the throne in 1588, the Safavid realm was still plagued by domestic issues, and thus the Ottomans managed to push further, taking Baghdad during that year and Ganja shortly after.[1] Confronted by even more problems (i.e. civil wars, uprisings,[6] and the war against the Uzbeks in the northeastern part of the realm), Abbas I agreed to sign a humiliating treaty with disadvantageous terms.[7][8]

Treaty

According to the treaty, the Ottoman Empire kept most of its gains in the war. These included most of the southern Caucasus (which included the Safavid domains in Georgia, composed of the Kingdoms of Kartli and Kakheti and the eastern part of the Samtskhe-Meskheti principality, as well as the Erivan Province, Karabakh, and Shirvan), the Azerbaijan Province (including Tabriz, but not Ardabil, which remained in Safavid hands), Luristan, Dagestan, most of the remaining parts of Kurdistan, Shahrizor, Khuzestan, Baghdad and Mesopotamia.[9] A clause was included in the treaty that stipulated that the Safavids would have to stop cursing the first three caliphs,[10][11] as was common ever since the first major Ottoman-Safavid treaty, namely the Peace of Amasya (1555). The Persians also agreed to pay obeisance to religious leaders of the Sunni faith.

Aftermath

This treaty was a success for the Ottoman Empire, as vast areas had been annexed. However, the new status quo did not last for long. Abbas I would use the time and resources which resulted from the peace on the main front with the Ottomans, to successfully deal with the other issues (including the Uzbeks and other revolts), while waiting for a suitable moment to regain his possessions.[12][2] When the Ottoman Empire during the reign of young sultan Ahmet I was engaged with the Celali revolts, he was able to regain most of his losses, which the Ottoman Empire had to accept in the Treaty of Nasuh Pasha, 22 years after this treaty.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Roemer 1986, p. 266.

- ^ a b Mitchell 2009, p. 178.

- ^ a b Mikaberidze 2011, p. 698.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2011, pp. 95, 698.

- ^ Floor 2001, p. 85.

- ^ Such as in Shirvan, which was sparked due to heavy taxation (Matthee (1999), p. 21)

- ^ Bengio & Litvak 2014, p. 61.

- ^ Prof. Yaşar Yücel-Prof. Ali Sevim:Türkiye Tarihi III, AKDTYKTTK Yayınları, 1991, pp. 21–23, 43–44

- ^ Mikaberidze (2011), p. 698; Meri & Bacharach (2006), p. 581; Iorga (2009), p. 213; Floor & Herzig (2015), p. 474; Newman (2012), p. 52; Bengio & Litvak (2014), p. 61; Mitchell (2009), p. 178

- ^ Floor & Herzig 2015, p. 474.

- ^ Newman 2012, p. 52.

- ^ Blow 2009, p. 36.

Sources

- Bengio, Ofra; Litvak, Meir (2014). Epilogue: The Sunni-Shi'i paradox. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 405. ISBN 978-0-2301-2092-1.

- Blow, David (2009). Shah Abbas: The Ruthless King Who Became an Iranian Legend. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0857716767.

- Floor, Willem (2001). Safavid Government Institutions. Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers. ISBN 978-1568591353.

- Floor, Willem; Herzig, Edmund, eds. (2015). Iran and the World in the Safavid Age. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1780769905.

- Iorga, Nicolae: Geschichte des Osmanischen Reichs Vol. III, (trans: Nilüfer Epçeli) Yeditepe Yayınları, 2009, ISBN 975-6480-20-3

- Matthee, Rudolph P. (1999). The Politics of Trade in Safavid Iran: Silk for Silver, 1600-1730. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521641319.

- Meri, Josef W.; Bacharach, Jere L. (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: L-Z, index. Taylor & Francis. p. 581. ISBN 978-0415966924.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander, ed. (2011). "Ottoman-Safavid Wars". Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1598843361.

- Mitchell, Colin p. (2009). The Practice of Politics in Safavid Iran: Power, Religion and Rhetoric. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0857715883.

- Newman, Andrew J. (2012). Safavid Iran: Rebirth of a Persian Empire. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0857716613.

- Roemer, H. R. (1986). "The Safavid Period". In Jackson, Peter; Lockhart, Laurence (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 6. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139054980.