Italian War of 1542–1546

| Italian War of 1542–1546 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Italian Wars | |||||||

The siege of Nice by a Franco-Ottoman fleet in 1543 (drawing by Toselli, after an engraving by Aeneas Vico) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Kingdom of France[Ottoman Empire]] |

Holy Roman Empire Electorate of Saxony Brandenburg Spain England | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

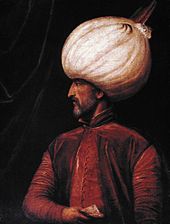

Francis I Dauphin Henri Duke of Orléans Count of Enghien Claude d'Annebault Suleiman I Hayreddin Barbarossa |

Charles V Alfonso d'Avalos René of Nassau-Chalon Ferrante Gonzaga Maurice of Saxony Maximiliaan van Egmond Henry VIII of England Duke of Norfolk Duke of Suffolk Viscount Lisle | ||||||

The Italian War of 1542–1546 was a conflict late in the Italian Wars, pitting Francis I of France and Suleiman I of the Ottoman Empire against the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and Henry VIII of England. The course of the war saw extensive fighting in Italy, France, and the Low Countries, as well as attempted invasions of Spain and England. The conflict was inconclusive and ruinously expensive for the major participants.

The war arose from the failure of the Truce of Nice, which ended the Italian War of 1536–1538, to resolve the long-standing conflict between Charles and Francis—particularly their conflicting claims to the Duchy of Milan. Having found a suitable pretext, Francis once again declared war against his perpetual enemy in 1542. Fighting began at once throughout the Low Countries; the following year saw the Franco-Ottoman alliance's attack on Nice, as well as a series of maneuvers in Northern Italy which culminated in the bloody Battle of Ceresole. Charles and Henry then proceeded to invade France, but the long sieges of Boulogne-sur-Mer and Saint-Dizier prevented a decisive offensive against the French.

Charles came to terms with Francis by the Treaty of Crépy in late 1544, but the death of Francis's younger son, the Duke of Orléans—whose proposed marriage to a relative of the Emperor was the foundation of the treaty—made it moot less than a year afterwards. Henry, left alone but unwilling to return Boulogne to the French, continued to fight until 1546, when the Treaty of Ardres finally restored peace between France and England. The deaths of King Francis of France and King Henry VIII of England, in early 1547 left the resolution of the Italian Wars to their successors.

Prelude

The Truce of Nice, which ended the Italian War of 1536–1538, provided little resolution to the long conflict between the Holy Roman Emperor and the King of France; although hostilities had ended, giving way to a cautious entente, neither monarch was satisfied with the war's outcome. Francis continued to harbor a desire for the Duchy of Milan, to which he held a dynastic claim; Charles, for his part, insisted that Francis comply at last with the terms of the Treaty of Madrid, which had been forced on the French king during his captivity in Spain after the Italian War of 1521–26.[1] Other conflicting claims to various territories—Charles's to Burgundy and Francis's to Naples and Flanders, among others—remained a matter of contention as well.

Negotiations between the two powers continued through 1538 and into 1539. In 1539, Francis invited Charles—who faced a rebellion in the Low Countries—to travel through France on his way north from Spain.[2] Charles accepted, and was richly received; but while he was willing to discuss religious matters with his host—the Protestant Reformation being underway—he delayed on the question of political differences, and nothing had been decided by the time he left French territory.[3]

In March 1540, Charles proposed to settle the matter by having Maria of Spain marry Francis's younger son, the Duke of Orléans; the two would then inherit the Netherlands, Burgundy, and Charolais after the Emperor's death.[4] Francis, meanwhile, was to renounce his claims to the duchies of Milan and Savoy, ratify the treaties of Madrid and Cambrai, and join an alliance with Charles.[5] Francis, considering the loss of Milan too large a price to pay for future possession of the Netherlands and unwilling to ratify the treaties in any case, made his own offer; on 24 April, he agreed to surrender the Milanese claim in exchange for immediate receipt of the Netherlands.[6] The negotiations continued for weeks, but made no progress, and were abandoned in June 1540.[7]

Francis soon began gathering new allies to his cause. William, Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg, who was engaged in the Guelders Wars, a dispute with Charles over the succession in Guelders, sealed his alliance with Francis by marrying Francis's niece, Jeanne d'Albret.[8] Francis sought an alliance with the Schmalkaldic League as well, but the League demurred; by 1542, the remaining potential French allies in northern Germany had reached their own understandings with the Emperor.[9] French efforts farther east were more fruitful, leading to a renewed Franco-Ottoman alliance; Suleiman the Magnificent of the Ottoman Empire, seeking to distract Charles from Ottoman advances in Hungary, encouraged the Franco-Imperial rift.[10]

On 4 July 1541, however, the French ambassador to the Ottoman court, Antoine de Rincon, was killed by Imperial troops as he was travelling near Pavia.[11] In response to Francis's protests, Charles denied all responsibility, promising to conduct an inquiry with the assistance of the Pope; he had by now formed plans for a campaign in North Africa, and wished to avoid further entanglements in Europe.[12]

By the end of September, Charles was in Majorca, preparing an attack on Algiers; Francis, considering it impolitic to attack a fellow Christian who was fighting the Muslims, promised not to declare war for as long as the Emperor was campaigning.[13] The Imperial expedition, however, was entirely unsuccessful; storms scattered the invasion fleet soon after the initial landing, and Charles had returned to Spain with the remainder of his troops by November.[14] On 8 March 1542, the new French ambassador, Antoine Escalin des Eymars, returned from Constantinople with promises of Ottoman aid in a war against Charles.[13] Francis declared war on 12 July, naming various injuries as the causes; among them was Rincon's murder, which he proclaimed "an injury so great, so detestable and so strange to those who bear the title and quality of prince that it cannot be in any way forgiven, suffered or endured".[15]

Initial moves and the Treaty of Venlo

The French immediately launched a two-front offensive against Charles. In the north, the Duke of Orléans attacked Luxembourg, briefly capturing the city; in the south, a larger army under Claude d'Annebault and King Francis's eldest son, the Dauphin Henri, unsuccessfully besieged the city of Perpignan in northern Spain.[16] Francis himself was meanwhile in La Rochelle, dealing with a revolt caused by popular discontent with a proposed reform of the gabelle tax.[17]

By this point, relations between Francis and Henry VIII were collapsing. Henry—already angered by the French refusal to pay the various pensions, which were owed to him under the terms of past treaties—was now faced with the potential of French interference in Scotland, where he was entangled in the midst of an attempt to marry his son to Mary, Queen of Scots, that would develop into the open warfare of the "Rough Wooing".[18] He had intended to begin a war against Francis in the summer of 1543, but negotiating a treaty to that effect with the Emperor proved difficult; since Henry was, in Charles's eyes, a schismatic, the Emperor could not promise to defend him against attack, nor sign any treaty which referred to him as the head of the Church—both points upon which Henry insisted.[19] Negotiations continued for weeks; finally, on 11 February 1543, Henry and Charles signed a treaty of offensive alliance, pledging to invade France within two years.[20] In May, Henry sent Francis an ultimatum threatening war within twenty days; and, on 22 June, at last declared war.[21]

Hostilities now flared up across northern France. On Henry's orders, Sir John Wallop crossed the Channel to Calais with an army of 5,000 men, to be used in the defense of the Low Countries.[22] The French, under Antoine de Bourbon, Duke of Vendôme, had captured Lillers in April; by June, d'Annebault had taken Landrecies as well.[23] Wilhelm of Cleves openly joined the war on Francis's side, invading Brabant, and fighting began in Artois and Hainaut.[18] Francis inexplicably halted with his army near Rheims; in the meantime, Charles attacked Wilhelm of Cleves, invading the Duchy of Jülich and capturing Düren.[24]

Concerned about the fate of his ally, Francis ordered the Duke of Orléans and d'Annebault to attack Luxembourg, which they took on 10 September; but it was too late for Wilhelm, as he had already surrendered on 7 September, signing the Treaty of Venlo with Charles.[25] By the terms of this treaty, Wilhelm was to concede the overlordship of the Duchy of Guelders and County of Zutphen to Charles, and to assist him in suppressing the Reformation.[26] Charles now advanced to besiege Landrecies, seeking battle with Francis; the French defenders of the town, commanded by Martin du Bellay, repulsed the Imperial attack, but Francis withdrew to Saint-Quentin on 4 November, leaving the Emperor free to march north and seize Cambrai.[27]

Nice and Lombardy

On the Mediterranean, meanwhile, other engagements were underway. In April 1543, the Sultan had placed Hayreddin Barbarossa's fleet at the disposal of the French king. Barbarossa left the Dardanelles with more than a hundred galleys, raided his way up the Italian coast, and in July arrived in Marseilles, where he was welcomed by François de Bourbon, Count of Enghien, the commander of the French fleet.[28] On 6 August, the joint Franco-Ottoman fleet anchored off the Imperial city of Nice and landed troops at Villefranche; a siege of the city followed.[29] Nice fell on 22 August, although the citadel held out until the siege was lifted on 8 September.[30]

Barbarossa was by this point becoming a liability; on 6 September, he had threatened to depart if he were not given the means with which to resupply his fleet.[31] In response, Francis ordered that the population of Toulon—except for "heads of households"—be expelled, and that the city then be given to Barbarossa, who used it as a base for his army of 30,000 for the next eight months.[32] Yet Francis, increasingly embarrassed by the Ottoman presence, was unwilling to help Barbarossa recapture Tunis, which had been captured by Charles in 1535; so the Ottoman fleet—accompanied by five French galleys under Antoine Escalin des Aimars—sailed for Istanbul in May 1544, pillaging the Neapolitan coast along the way.[33]

In Piedmont, meanwhile, a stalemate had developed between the French, under the Sieur de Boutières, and the Imperial army, under Alfonso d'Avalos; d'Avalos had captured the fortress of Carignano, and the French had besieged it, hoping to force the Imperial army into a decisive battle.[34] During the winter of 1543–44, Francis significantly reinforced his army, placing Enghien in command.[35] D'Avalos, also heavily reinforced, advanced to relieve Carignano; and, on 11 April 1544, Enghien and d'Avalos fought one of the few pitched battles of the period at Ceresole.[36] Although the French were victorious, the impending invasion of France itself by Charles and Henry forced Francis to recall much of his army from Piedmont, leaving Enghien without the troops he needed to take Milan.[37] D'Avalos's victory over an Italian mercenary army in French service at the Battle of Serravalle in early June 1544 brought significant campaigning in Italy to an end.[38]

Danish-Norwegian participation

Emperor Charles V's refusal to recognize Christian of Holstein as King of Denmark and Norway, led to the Danish-French alliance in 1541.[39] Denmark-Norway declared war on the Netherlands, at that time under Charles's rule. Denmark-Norway, were to blockade The Sound and the Belt to Dutch shipping,[39][40] and a Danish contingent joined the Franco-Cleves army, which invaded Brabant in July.[41] Additionally fleet of 26 Danish vessels patrolled the North Sea.[41] After a failed attempt by Hamburg to mediate between the belligerents, a Danish fleet of 40 ships and 10.000 men, set sail for the Walcheren.[41] Yet this fleet would be scattered by a storm.[41] In the Holsteinian-Imperial border, Johann Rantzau prevented an invasion from Germany.[41]

A peace treaty was signed, between Denmark-Norway and the Holy Roman Empire, in 1544 at Speyer; Charles acknowledged Christian III as king of Denmark and Norway and free passage through the Sound (Øresund) was ensured.[39]

Invasion of France

On 31 December 1543, Henry and Charles had signed a treaty pledging to invade France in person by 20 June 1544; each was to provide an army of no less than 35,000 infantry and 7,000 cavalry for the venture.[42] Against this Francis could muster about 70,000 men in his various armies.[43] The campaign could not begin, however, until Henry and Charles had resolved their personal conflicts with Scotland and the German princes, respectively.[44] On 15 May, Henry was informed by Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, that, after his raids, Scotland was no longer in a position to threaten him; he then began to make preparations for a personal campaign in France—against the advice of his council and the Emperor, who believed that his presence would be a hindrance.[45] Charles had meanwhile reached an understanding with the princes at the Diet of Speyer, and the Electors of Saxony and Brandenburg had agreed to join his invasion of France.[46]

By May 1544, two Imperial armies were poised to invade France: one, under Ferrante Gonzaga, Viceroy of Sicily, north of Luxemburg; the other, under Charles himself, in the Palatinate.[44] Charles had gathered a combined force of more than 42,000 for the invasion, and had arranged for another 4,000 men to join the English army.[47] On 25 May, Gonzaga captured Luxembourg and moved towards Commercy and Ligny, issuing a proclamation that the Emperor had come to overthrow "a tyrant allied to the Turks".[48] On 8 July, Gonzaga besieged Saint-Dizier; Charles and the second Imperial army soon joined him.[49]

Henry, meanwhile, had sent an army of some 40,000 to Calais under the joint command of Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, and Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk.[50] This force consisted of 36,000 infantry (including 8,000 Landsknecht) and 6,000 cavalry (including another 2,000 German mercenaries). It was organized into three armies, one of 16,000 and two of 13,000 each. By western continental standards, the army was obsolescent; it had little heavy cavalry and a shortage of both pike and shot, the bulk of its troops being armed with longbows or bills. The few cuirassiers and arquebusiers, the latter only accounting for single digit percentages of the host, were mostly foreign mercenaries.[51] Henry hired additional arquebusiers from Italy, but still only 2,000 of the 28,000 soldiers who besieged Boulogne that year were equipped with firearms.[52]

While Henry continued to squabble with the Emperor over the goals of the campaign and his own presence in France, this massive army moved slowly and aimlessly into French territory.[53] Finally, Henry decided that the army was to be split. Norfolk, ordered to besiege Ardres or Montreuil, advanced towards the latter; but he proved unable to mount an effective siege, complaining of inadequate supplies and poor organization.[54] Suffolk was ordered to attack Boulogne; on 14 July, Henry crossed to Calais and moved to join him.[55] A siege of Boulogne began on 19 July—despite the protests of the Emperor, who insisted that Henry should advance towards Paris.[56]

Charles himself, on the other hand, was still delayed at Saint-Dizier; the city, fortified by Girolamo Marini and defended by Louis IV de Bueil, Count of Sancerre, continued to hold out against the massive Imperial army.[57] On 24 July, Charles captured Vitry-en-Perthois, from which French forces had harassed his supply lines; finally, on 8 August, the defenders of Saint-Dizier, running low on supplies, sought terms.[58] On 17 August, the French capitulated, and were permitted by the Emperor to leave the city with banners flying; their resistance for 41 days had broken the Imperial offensive.[59] Some of Charles's advisers suggested withdrawing, but he was unwilling to lose face and continued to move towards Châlons, although the Imperial army was prevented from advancing across the Marne by a French force waiting at Jâlons.[60] The Imperial troops marched rapidly through Champagne, capturing Épernay, Châtillon-sur-Marne, Château-Thierry, and Soissons.[61]

The French made no attempts to intercept Charles. Troops under Jacques de Montgomery, Sieur de Lorges, sacked Lagny-sur-Marne, whose citizens had allegedly rebelled; but no attempt was made to engage the advancing Imperial army.[62] Paris was gripped by panic, although Francis insisted that the population had nothing to fear.[63] Charles finally halted his advance and turned back on 11 September.[64] Henry, meanwhile, was personally directing the besiegers at Boulogne; the town fell in early September, and a breach was made into the castle on 11 September.[65] The defenders finally surrendered a few days later.[66]

Treaty of Crépy

Charles, short on funds and needing to deal with increasing religious unrest in Germany, asked Henry to continue his invasion or to allow him to make a separate peace.[67] By the time Henry had received the Emperor's letter, however, Charles had already concluded a treaty with Francis—the Peace of Crépy—which was signed by representatives of the monarchs at Crépy in Picardy on 18 September 1544.[68] The treaty had been promoted at the French court by the Emperor's sister, Queen Eleanor, and by Francis's mistress, the Duchess of Étampes. By its terms, Francis and Charles would each abandon their various conflicting claims and restore the status quo of 1538; the Emperor would relinquish his claim to the Duchy of Burgundy and the King of France would do the same for the Kingdom of Naples, as well as renouncing his claims as suzerain of Flanders and Artois.[69] The Duke of Orléans would marry either Charles's daughter Mary or his niece Anna; the choice was to be made by Charles. In the first case, the bride would receive the Netherlands and Franche-Comté as a dowry; in the second, Milan. Francis, meanwhile, was to grant the duchies of Bourbon, Châtellerault, and Angoulême to his son; he would also abandon his claims to the territories of the Duchy of Savoy, including Piedmont and Savoy itself. Finally, Francis would assist Charles against the Ottomans—but not, officially, against the heretics in his own domains.[70] A second, secret accord was also signed; by its terms, Francis would assist Charles with reforming the church, with calling a General Council, and with suppressing Protestantism—by force if necessary.[71]

The treaty was poorly received by the Dauphin, who felt that his brother was being favored over him, by Henry VIII, who believed that Charles had betrayed him, and also by the Sultan.[72] Francis would fulfill some of the terms; but the death of the Duke of Orléans in 1545 rendered the treaty moot.[73]

Boulogne and England

The conflict between Francis and Henry continued. The Dauphin's army advanced on Montreuil, forcing Norfolk to raise the siege; Henry himself returned to England at the end of September 1544, ordering Norfolk and Suffolk to defend Boulogne.[74] The two dukes quickly disobeyed this order and withdrew the bulk of the English army to Calais, leaving some 4,000 men to defend the captured city.[75] The English army, outnumbered, was now trapped in Calais; the Dauphin, left unopposed, concentrated his efforts on besieging Boulogne.[76] On 9 October, a French assault nearly captured the city, but was beaten back when the troops prematurely turned to looting.[77] Peace talks were attempted at Calais without result; Henry refused to consider returning Boulogne, and insisted that Francis abandon his support of the Scots.[78] Charles, who had been appointed as a mediator between Francis and Henry, was meanwhile drawn into his own disputes with the English king.[79]

Francis now embarked on a more dramatic attempt to force Henry's hand—an attack on England itself. For this venture, an army of more than 30,000 men was assembled in Normandy, and a fleet of some 400 vessels prepared at Le Havre, all under the command of Claude d'Annebault.[80] On 31 May 1545, a French expeditionary force landed in Scotland.[81] In early July, the English under John Dudley, Viscount Lisle, mounted an attack on the French fleet, but had little success due to poor weather; nevertheless, the French suffered from a string of accidents: d'Annebault's first flagship burned, and his second ran aground.[82] Finally leaving Le Havre on 16 July, the massive French fleet entered the Solent on 19 July and briefly engaged the English fleet, to no apparent effect; the major casualty of the skirmish, the Mary Rose, sank accidentally.[83] The French landed on the Isle of Wight on 21 July, and again at Seaford on 25 July, but these operations were abortive, and the French fleet soon returned to blockading Boulogne.[84] D'Annebault made a final sortie near Beachy Head on 15 August, but retired to port after a brief skirmish.[82]

Treaty of Ardres

By September 1545, the war was a virtual stalemate; both sides, running low on funds and troops, unsuccessfully sought help from the German Protestants.[85] Henry, Francis, and Charles attempted extensive diplomatic maneuvering to break the deadlock; but none of the three trusted the others, and this had little practical effect.[86] In January 1546, Henry sent the Earl of Hertford to Calais, apparently preparing for an offensive; but one failed to materialize.[87]

Francis could not afford to resume a large war, and Henry was concerned only for the disposition of Boulogne. Negotiations between the two resumed on 6 May.[88] On 7 June 1546, the Treaty of Ardres—also known as the Treaty of Camp—was signed by Claude d'Annebault, Pierre Ramon, and Guillaume Bochetel on behalf of Francis, and Viscount Lisle, Baron Paget and Nicholas Wotton on behalf of Henry.[89] By its terms, Henry would retain Boulogne until 1554, then return it in exchange for two million écus; in the meantime, neither side would construct fortifications in the region, and Francis would resume payment of Henry's pensions. Upon hearing the price demanded for Boulogne, the Imperial ambassador told Henry that the city would remain in English hands permanently.[90]

During the treaty negotiations, two Protestant mediators—Han Bruno of Metz and Johannes Sturm—were concerned that Henry's war in Scotland was a stumbling block. The sixteenth article of the treaty made Scotland a party to the new peace, and Henry pledged not to attack the Scots again without cause.[91] This gave Scotland a respite from the War of the Rough Wooing, but the fighting would recommence 18 months later.[92]

Aftermath

Exorbitantly expensive, the war was the costliest conflict of both Francis's and Henry's reigns.[93] In England, the need for funds led to what Elton terms "an unprecedented burden of taxation", as well as the systematic debasement of coinage.[94] Francis also imposed a series of new taxes and instituted several financial reforms.[95] He was not, therefore, in a position to assist the German Protestants, who were now engaged in the Schmalkaldic War against the Emperor; by the time any French aid was to be forthcoming, Charles had already won his victory at the Battle of Mühlberg.[96] As for Suleiman, the conclusion of the Truce of Adrianople in 1547 brought his own struggle against the Habsburgs to a temporary halt.[97]

Henry VIII of England died on 28 January 1547 and was succeeded by his son Edward VI ; on 31 March, the death of King Francis followed and was succeeded by his son, Henry II of France.[98] Henry's successors continued his entanglements in Scotland; when, in 1548, friction with the Scots led to the resumption of hostilities around Boulogne, they decided to avoid a two-front war by returning the city four years early, in 1550.[99] As successor to King Francis, king Henry II of France had ambitions in Italy and hostility towards Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, which soon led to the Italian War of 1551–1559.[100]

Notes

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 385–387.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 389–391.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 391–393. Knecht writes that "the Emperor's itinerary from Loches northwards had evidently been devised to show him the principal artistic achievements of [Francis's] reign.... no expense had been spared to make his stay memorable" (Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 392).

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 394. The proposal specified, however, that the territories would revert to the Habsburg line if Mary died childless. Several other marriages between the Habsburg and Valois were also considered—notably one between Charles's son Phillip and Jeanne d'Albret.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 394. Knecht, citing Brandi, terms the proposed alliance "a league in defence of Christendom" (Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 394).

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 394–395.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 395. The failure of the negotiations led to the downfall of Anne de Montmorency, who had been their chief proponent; for more details, see Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 395–397.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 396.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 478. Among other factors, the German Protestants were critical of the treatment accorded to the Huguenots in France.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 478–479.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 479. Also killed was one Cesare Fregoso, a diplomat in French employ on his way to Venice.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 479. The Pope's intervention was requested by Francis himself.

- ^ a b Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 479.

- ^ Arnold, Renaissance at War, 144–145; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 479. The Imperial troops abandoned their horses—those they had not been forced to eat—and their guns as they evacuated.

- ^ Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 72; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 479–480.

- ^ Black, European Warfare, 80; Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 72; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 480.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 480. For more details of the gabelle revolt, see Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 480–483.

- ^ a b Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 486.

- ^ Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 388–389. The matter of royal style was finally resolved by referring to Henry as "Defender of the Faith, etc." in the final documents.

- ^ Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 72; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 486; Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 388–389.

- ^ Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 72; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 486; Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 389. Elton argues that the only explanation for this move is that Henry believed his Scottish entanglements to be concluded (Elton, England Under the Tudors, 194).

- ^ Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 389.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 486–487.

- ^ Black, European Warfare, 80; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 487.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 487. Wilhelm's surrender made his marriage to Jeanne d'Albret pointless, and it was annulled in 1545.

- ^ Blockmans and Prevenier, Promised Lands, 232; Hughes, Early Modern Germany, 57.

- ^ Black, European Warfare, 80; Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 72; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 487.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 487.

- ^ Arnold, Renaissance at War, 180; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 487–488.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 488–489.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 489.

- ^ Arnold, Renaissance at War, 180; Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 72–73; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 489. The Ottomans opened a mosque and a slave market in the city, shocking European observers—who were, however, favorably impressed by the strict discipline of the Ottoman troops.

- ^ Crowley, Empires of the Sea, 75–79; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 489; Setton, Papacy and the Levant, 472–473. Knecht gives the date of the fleet's departure as 23 May, while Setton cites 26 May. Setton also notes that the Sultan, told by the French ambassador of the affair, "promised to pay for the supplies with which his fleet had been furnished" (Setton, Papacy and the Levant, 473).

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 490; Oman, Art of War, 229–230.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 229–230.

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 187–190; Oman, Art of War, 239–243.

- ^ Black, "Dynasty Forged by Fire", 43; Oman, Art of War, 242.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 490; Oman, Art of War, 242–243.

- ^ a b c Sicking, Louis (2006). "Amphibious Warfare in the Baltic: The Hansa, Holland and the Habsburgs". In Fissel, Trim; Fissel, Mark C. (eds.). Amphibious Warfare, 1000–1700. Brill. p. 91.

- ^ Donald J. Harreld (2004) The Dutch Economy in the Golden Age (16th – 17th Centuries) https://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-dutch-economy-in-the-golden-age-16th-17th-centuries/

- ^ a b c d e Bain 2023, p. 71.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 490; Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 389.

- ^ The number was a record high for the whole century; see John A. Lynn, "Recalculating French Army Growth during the Grand Siècle, 1610–1715", in Rogers, Military Revolution, 117–148.

- ^ a b Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 490.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 490; Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 393–394.

- ^ Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 73; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 490. Francis attempted to dispatch an embassy to the Diet, but was denied a safe-conduct; Knecht writes that his herald "was sent home after being told that he deserved to be hanged" (Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 490).

- ^ Tracy, Emperor Charles V, 196. Tracy cites a letter by Charles which gives the composition of the Imperial army as "16,000 High Germans, 10,000 Low Germans, 9,000 Spaniards, and 7,000 heavy cavalry" and the composition of the force sent to join the English as "2,000 Landsknechte and 2,000 cavalry" (Tracy, Emperor Charles V, 196).

- ^ Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 73; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 490–491.

- ^ Black, European Warfare, 81; Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 73; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 491.

- ^ Black, European Warfare, 81; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 491; Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 394.

- ^ Ian Heath. "Armies of the Sixteenth Century: The Armies of England, Ireland, the United Provinces, and the Spanish Netherlands 1487–1609." Foundry Books, 1997. p. 32.

- ^ Heath, p. 37.

- ^ Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 394. Scarisbrick relates that Norfolk wrote to the Privy Council that "he had expected to know, before this, where he was supposed to be going" (Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 394).

- ^ Black, European Warfare, 81; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 491; Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 394–395.

- ^ Elton, England Under the Tudors, 195; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 491; Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 395. Henry could not ride, and was carried in a litter; Elton notes that "at fifty-four Henry was in fact an old man" (Elton, England Under the Tudors, 195).

- ^ Arnold, Renaissance at War, 180; Black, European Warfare, 81; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 491; Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 395.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 491. Knecht notes that Marini was "one of the best military engineers of his day" (Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 491).

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 491.

- ^ Arnold, Renaissance at War, 180; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 491.

- ^ Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 73; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 491–492.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 492.

- ^ Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 73; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 492.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 492–493.

- ^ Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 73; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 493.

- ^ Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 395. Henry apparently greatly enjoyed the proceedings of the siege.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 493; Phillips, "Testing the 'Mystery'", 47; Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 395.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 493.

- ^ Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 74; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 493. At the time of the treaty, "Crépy" was spelt "Crespy", so the treaty is also known as the "Treaty of Crespy"; see The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013), s.v. "Crespy, Treaty of", http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1E1-X-Crespy.html (accessed 22 July 2014).

- ^ Armstrong, Emperor Charles V, 28.

- ^ Armstrong, Emperor Charles V, 28–29; Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 74; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 493. Charles was to make the choice of bride within four months of the treaty.

- ^ Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 74; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 493. Blockmans notes that Francis pledged to provide 10,000 infantry and 400 cavalry to Charles for a venture against the Protestants.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 493–494; Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 396. Knecht, citing Rozet, Lembey, and Charriere, notes that the Sultan "nearly had the French ambassador impaled" (Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 494).

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 494.

- ^ Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 395–396.

- ^ Phillips, "Testing the 'Mystery'", 47; Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 396–397.

- ^ Elton, England Under the Tudors, 195; Phillips, "Testing the 'Mystery'", 47, 51–52; Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 397.

- ^ Arnold, Renaissance at War, 180; Phillips, "Testing the 'Mystery'", 48–50.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 501; Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 397–398.

- ^ Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 398–399.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 502; Phillips, "Testing the 'Mystery'", 50–51. Although d'Annebault bore the title of "Admiral", he had no experience in naval warfare.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 501–502.

- ^ a b Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 502.

- ^ Elton, England Under the Tudors, 195; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 502; Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 401.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 502; Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 401–402.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 502–503; Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 399–400.

- ^ Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 404–407.

- ^ Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 408.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 503; Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 408.

- ^ Gairdner and Brodie, Letters & Papers, 507–509.

- ^ Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 409.

- ^ Elton, England Under the Tudors, 195; Gairdner and Brodie, Letters & Papers, 508; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 503; Phillips, "Testing the 'Mystery'", 52; Scarisbrick, Henry VIII, 409.

- ^ Merriman, Rough Wooings, 163, 195–201.

- ^ Elton, England Under the Tudors, 195; Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 503. The English war effort cost nearly two million pounds. Francis had needed more than two million écus for his navy alone, and was spending almost 250,000 écus per year on new fortifications.

- ^ Elton, England Under the Tudors, 195.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 504–507.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 517–518. Knecht writes that "in November [1546], Annebault declared that the imperial alliance needed to be preserved at all costs, regardless of the Protestants. By January 1547, however, the military situation had become so ominous for the Protestants that Francis saw the need to strengthen their hand" (Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 518).

- ^ Kinross, Ottoman Centuries, 234–235.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 541–542; Phillips, "Testing the 'Mystery'", 52.

- ^ Phillips, "Testing the 'Mystery'", 52.

- ^ Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 75; Mallett and Shaw, The Italian Wars, 250–255.

References

- Armstrong, Edward. The Emperor Charles V. Volume 2. London: Macmillan and Co., 1902.

- Arnold, Thomas F. The Renaissance at War. Smithsonian History of Warfare, edited by John Keegan. New York: Smithsonian Books / Collins, 2006. ISBN 0-06-089195-5.

- Black, Jeremy. "Dynasty Forged by Fire". MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History 18, no. 3 (Spring 2006): 34–43. ISSN 1040-5992.

- Black, Jeremy. European Warfare, 1494–1660. Warfare and History, edited by Jeremy Black. London: Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0-415-27532-6.

- Blockmans, Wim. Emperor Charles V, 1500–1558. Translated by Isola van den Hoven-Vardon. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-340-73110-9.

- Blockmans, Wim and Walter Prevenier. The Promised Lands: The Low Countries Under Burgundian Rule, 1369–1530. Translated by Elizabeth Fackelman. Edited by Edward Peters. The Middle Ages Series, edited by Ruth Mazo Karras. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8122-1382-3.

- Crowley, Roger. Empires of the Sea: The Siege of Malta, the Battle of Lepanto, and the Contest for the Center of the World. New York: Random House, 2008.

- Elton, G. R. England Under the Tudors. A History of England, edited by Felipe Fernández-Armesto. London: The Folio Society, 1997.

- Gairdner, James and R. H. Brodie, eds. Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, of the Reign of Henry VIII. Vol. 21, part 1. London, 1908.

- Hall, Bert S. Weapons and Warfare in Renaissance Europe: Gunpowder, Technology, and Tactics. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8018-5531-4.

- Hughes, Michael. Early Modern Germany, 1477–1806. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992. ISBN 0-8122-1427-7.

- Kinross, Patrick Balfour. The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire. New York: HarperCollins, 1977. ISBN 0-688-08093-6.

- Knecht, Robert J. Renaissance Warrior and Patron: The Reign of Francis I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-521-57885-X.

- Mallett, Michael and Christine Shaw. The Italian Wars, 1494–1559: War, State and Society in Early Modern Europe. Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited, 2012. ISBN 978-0-582-05758-6.

- Merriman, Marcus. The Rough Wooings: Mary Queen of Scots, 1542–1551. East Linton: Tuckwell Press, 2000. ISBN 1-86232-090-X.

- Oman, Charles. A History of the Art of War in the Sixteenth Century. London: Methuen & Co., 1937.

- Phillips, Charles and Alan Axelrod. Encyclopedia of Wars. Vol. 2. New York: Facts on File, 2005. ISBN 0-8160-2851-6.

- Phillips, Gervase. "Testing the 'Mystery of the English'". MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History 19, no. 3 (Spring 2007): 44–54. ISSN 1040-5992.

- Rogers, Clifford J., ed. The Military Revolution Debate: Readings on the Military Transformation of Early Modern Europe. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1995. ISBN 0-8133-2054-2.

- Scarisbrick, J. J. Henry VIII. London: The Folio Society, 2004.

- Setton, Kenneth M. The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571). Vol. 3, The sixteenth century to the reign of Julius III. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society, 1984. ISBN 0-87169-161-2.

- Tracy, James D. Emperor Charles V, Impresario of War: Campaign Strategy, International Finance, and Domestic Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 0-521-14766-2.

- Bain, Nisbet (2023). Scandinavia A Political History of Denmark, Norway and Sweden from 1512 to 1900. CUP Archive. p. 71.