Tom Johnson (bareknuckle boxer)

Tom Johnson (born Thomas Jackling; c. 1750 – 21 January 1797) was a bare-knuckle fighter who was referred to as the Champion of England between 1784 and 1791. His involvement in pugilistic prizefighting is generally seen to have coincided with a renewed interest in the sport. Although a strong man, his success was largely attributed to his technical abilities and his calm, analytical approach to despatching his opponents. But Johnson was less prudent outside the ring; he was a gambler and considered by many of his acquaintances to be an easy mark. He is thought to have earned more money from the sport than any other fighter until nearly a century later, but much of it was squandered.

Johnson's first fight probably took place in June 1783 against Jack Jarvis, after he had unintentionally slighted the wagon driver and professional fighter. Jarvis challenged Johnson to fight him as a matter of honour, and was comprehensively beaten in the resulting match. Johnson's success encouraged him to take up the sport professionally. By June 1784 he had declared himself to be the champion, although whether of England or the world is uncertain.

In the later years of his fight career, and for some time after it ended, he acted as a second for other prominent fighters and ran a public house. His dissipation outside the ring appears to have resulted in his decision to leave England for Ireland, where he continued to tutor other boxers but eventually resorted to gambling to earn a living. He died a broken man, both physically and financially.

Johnson was inducted into the Pioneer category of the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1995.[1][2]

Life before boxing

Tom Johnson was born in Derby, England in about 1750, although Pierce Egan, an early historian of boxing, states that Johnson was born in Yorkshire.[3] His birth name was Thomas Jackling, but he used the name Tom Johnson throughout his fight career.[4]

Johnson moved to London at a young age and spent the next twenty years or so[3] working as a corn porter, loading and unloading sacks of corn from a wharf near to Old Swan Stairs, (Upper) Thames Street.[3][5][6]

His selflessness and strength were exemplified during this period by the assistance that he gave to a fellow worker who had become ill. Johnson would carry two sacks of corn on each journey between the wharf and the grain warehouse, rather than the usual single sack, up an incline so steep that it was known as Labour-in-vain-hill. He gave the extra money he earned to the family of the sick man until he was able to return work.[7]

Background to 18th-century prizefighting

Prizefighting in early 18th-century England took many forms rather than just pugilism, which was referred to by noted swordsman and then boxing champion James Figg as "the noble science of defence". But by the middle of the century the term was generally used to denote boxing fights only.[8] The appeal of prizefighting at that time has been compared to that of duelling; historian Adrian Harvey says that:

Patriotic writers often extolled the manly sports of the British, claiming that they reflected a courageous, robust, individualism in which the nation could take pride. Pugilism was regarded as humane and fair and its practice was presented in chivalrous terms. It was also a symbol of national courage, embodying the worth which Englishmen placed upon their own individual honour. The French, it was argued, did not like pugilism because they were not a free people and relied on the authorities to resolve their disputes. By contrast, the British dealt with their own problems in a straightforward manner, according to established rules of fair play.[9]

From a legal standpoint prizefights ran the risk of being classified as disorderly assemblies, but in practice the authorities were mainly concerned about the number of criminals congregating there. Historian Bohun Lynch has been quoted as saying that pickpocketing was rife, and that fights between the various supporters were common.[10] However, the patronage of the aristocracy and the wealthy ensured that any legal scrutiny was generally benign, in particular because fights could take place on private estates.[9][11] This patronage also explains why London was the centre for the sport; people of wealth tended to congregate in the city during the winter months and in the summer dispersed to their country estates.[11] From 1786, just as Johnson was rising to prominence, there was increased support for the sport because of the interest shown in it by the Prince of Wales (later King George IV) and his brothers, the future King William IV and Duke of Kent.[4] This renewed interest followed a period of malaise which had in large part been due to corruption in the form of "fixing" the fights.[12]

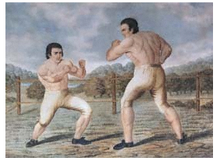

Jack Broughton, a celebrated boxing champion (and another who was also a swordsman),[8] had gone some way to defining the rules of prizefighting in 1743, based on earlier work by Figg, but by Johnson's time the rules were still interpreted very loosely.[11][13] The style of fighting was also very different from modern boxing; the contestants stood facing each other squarely with their feet in line and their fists raised level in front of them, rather than the present-day stance of generally having one foot slightly in front of the other and one fist leading. Brute strength was the primary factor for success and knock-downs were frequent, a consequence of the instability inherent in the positioning of the fighters' feet. Rounds were not timed but instead lasted until a man was knocked down, with fighters permitted to wrestle each other to the ground. Moving around the ring, known as shifting, was deprecated and sometimes explicitly prohibited by the rules for a fight;[14] going to ground without being hit could lead to claims that the man still standing had won. The fighters usually each provided an umpire of their choice, and there might also be a third, independent umpire present, to adjudicate between them.[15]

Career as a fighter

Early period

Johnson probably began fighting in June 1783,[16][17] at the age of thirty-three, although Brailsford suggests it was 1781 or slightly earlier.[4] Johnson had unintentionally slighted a carman (horse-drawn wagon driver) and fighter called Jack Jarvis, who then called for Johnson to fight him as a matter of honour. Johnson comprehensively battered the experienced Jarvis at Lock's Fields,[17] and his name came to the attention of professional fighters. At that time Johnson had no intention of earning a living from the sport, but he became so goaded by a professional known as The Croydon Drover that a fight was arranged for March 1784, at Kennington Common. Johnson beat the Drover to a pulp in 27 minutes and decided to become a professional.[16]

The success against the Drover was followed by a victory against the ageing professional Stephen "Death" Oliver in June. The fight, which took place at Blackheath in front of thousands of people, was over in a time stated as being either 18[5] or 35 minutes.[16] Johnson subsequently declared himself to be the champion and challenged all-comers. Most contemporary and near-contemporary accounts, such as those of Egan, regard this title of champion to mean Champion of England but Barrett O'Hara, writing in 1909, listed Johnson as the fourteenth World Heavyweight Champion. At the time of Johnson's victory, the holder of title of champion was disputed. The previous holder, Duggan Fearns, had disappeared and Harry Sellers, the man Fearns had beaten to win the title in a fight that lasted 90 seconds and was alleged to have been fixed, had died.[16]

Johnson did not fight again until he beat Bill Love, a butcher, at Barnet on 11 or 13 January 1786 in a contest that lasted five minutes and offered a prize of 50 guineas. He then beat Jack Towers the following month at the same place.[5][16][18]

The final fight of Johnson's early period, during which the stake money was relatively low, was his comprehensive win over a ponderous fighter called Fry for a prize of 50 guineas at Kingston. The fight, which lasted less than 30 minutes, ended with Fry badly beaten up and Johnson with barely a scratch on him. This fight did not attract many supporters of the sport; it took place on 6 June 1786 and was therefore during the period when the wealthy were away from London.[4][5][16]

Consolidation

Johnson had developed to be an exceptional fighter, and a rarity in his day because he used his brain as well as his strength.[14] A barrel-chested man,[14] he weighed around 196 pounds (89 kg) and his height was variously stated in the range of 5' 8" (1.73 m)[16] to 5' 10" (1.78 m).[19] He was known for his coolness under pressure and he took time to analyse his opponent's strengths, weaknesses and technique. He did not retreat from the fight but avoided risk and was careful not to expose himself too much to attack, although his guard was described as "inelegant" by Egan. That writer also explained that he "worked round his antagonist in a way peculiar to himself, that so puzzled his adversary to find out his intent, that he was frequently thrown off his guard, by which manoeuvring Johnson often gained the most important advantages."[4][20] All of this meant that his fights were not usually of short duration; he made certain of the outcome rather than risking anything.[14]

Having exhausted challengers in London, he took on Bristolian professional Bill Warr for 200 guineas at Oakhampton, Berkshire on 18 January 1787, although the manner of his victory on this occasion was "scarcely worthy of being called a fight", according to The Sportsman's Magazine.[5] Warr had to resort to shifting and falling to the ground in order to stay in the contest, and as both tactics were regarded as underhand he attracted the ire of the crowd. He survived for almost 90 minutes until a choice blow from Johnson caused Warr to run from the ring, despite the protestations of his second.[16][21][22][a]

A hiatus in Johnson's boxing career followed, with no challengers coming forward until the Irish champion Michael Ryan took an interest. The fight at Wraysbury,[23] then in Buckinghamshire, on either 18 or 19 December 1787 saw Richard Humphries ("The Gentleman Boxer") acting as Johnson's second and Daniel Mendoza as his bottle-holder. Ryan was the favourite to win before the fight, and he had Johnson reeling against the rails of the ring with a blow to the head after almost 20 minutes[24] had elapsed. Humphries' second stepped in to prevent a second strike and this enraged the crowd because they believed Ryan could continue hitting until Johnson fell to the ground. They encouraged Ryan to declare himself victor as a consequence of this foul but he refused, as he wanted to win by means other than a technicality. He allowed Johnson to recover and then, in the space of the next ten minutes, lost the bout.[16][21]

Financial security

The nature of the fight with Ryan led to a much anticipated re-match at Cassiobury Park, Hertfordshire on 11 February 1789. At stake was prize money of 600 guineas, as well as Johnson's title of champion. Humphries again acted as Johnson's second and a man called Jackson was his bottle-holder. The fight consisted of one round of mutually displayed skill, during which Johnson was felled, and thereafter was brutal passion. Egan described it as

The set-to was one of the finest ever witnessed and much science was displayed; the parries and feints eliciting general admiration ... [The second round] was terrible beyond description – science seemed forgotten – and they appeared like two blacksmiths at an anvil, when Ryan received a knock-down blow. The battle was well sustained on both sides for some time; but Ryan's passion getting the better of him, he began to lose ground. Ryan's head and eyes made a dreadful appearance and Johnson was severely punished.[25]

It was over in 33 minutes, when Ryan gave up the fight. One spectator, a Mr Hollingsworth, who was a corn factor and had at one time employed Johnson, was so impressed and pleased with how much he had made from betting on Johnson that he settled a £20 per annum gift for life on the fighter.[16][25]

A proposed bout later in the same year against Ben Bryan (sometimes known as Ben Brian, Ben Brain or Ben Bryant) came to nothing. Bryan had been a collier in Kingswood, Bristol before moving to London to fight. He was seen as a strong potential challenger, having already won two fights in the provinces and then won against John Boone (known as "The Fighting Grenadier"), a man called Corbally, and Tom Tring.[26] The prize money was set at £1000, but Bryan became ill and had to withdraw, forfeiting his staked deposit of £100.[16][21]

Later in 1789 fighters from the Birmingham area issued a series of challenges to opponents based around London, intended to demonstrate the level of organisation and confidence among the Birmingham boxers and their supporters.[27] Three of the challenges were accepted, including that from Isaac Perrins to Tom Johnson. Perrins, who has been described as "the knock-kneed hammerman from Soho",[28] had already issued a general challenge, offering to fight any man in England for a prize of 500 guineas, having beaten all challengers in the counties around Birmingham.[29]

The Perrins–Johnson fight took place at Banbury on 22 October 1789, billed as a battle between Birmingham and London as well as for the English Championship. The venue had been intended to be Newmarket during a race meeting but permission could not be obtained.[29] The two men were about the same age but physically very different.[19] Perrins stood 6' 2" (1.88 m) tall and weighed 238 pounds (108 kg). It was claimed that he had lifted 896 pounds (406 kg) of iron with ease,[30] and he was "universally allowed to possess much skill and excellent bottom".[29] That is, it was acknowledged that he was skillful and courageous. The physical mismatch was later described as a fight between Hercules, in the form of Perrins, and a boy.[31]

The first five minutes of competition saw neither man strike a blow and then when Perrins tried to make contact Johnson dodged and felled Perrins in return. Although Perrins recovered to hold the upper hand in the first few rounds, Johnson then began to dance around the ring, forcing Perrins to follow in order to make a fight of it. This was the first time in his career that Johnson had found it necessary to resort to this tactic of shifting.[21] It confused Perrins because of it being contrary to the custom at the time, but the rules for this particular fight did not prevent it. Nor did they specify what should happen if a contestant fell to the ground, which is what Johnson did in order to avoid being hit – this action was thought by the spectators to be unsporting but was permitted by the two umpires. Before long both fighters showed signs of their opponent's attacks, with first Perrins and then Johnson suffering cut eyes and then further damage to their faces. By the fight's end Perrins' head "had scarcely the traces left of a human being",[30] according to Egan in his history of boxing. The contest lasted 62 rounds, which took a total of 75 minutes to complete, until Perrins became totally exhausted.[4][30][32][33] Tony Gee has said that

Perrins had overwhelming physical advantages but, owing to his naïvety, no clause was inserted in the articles of agreement to prevent "shifting" ... Moreover, Perrins was inexperienced in the subterfuges of the sport and found himself outwitted by his artful adversary.[4]

Perrins' supporters had gambled heavily on him because of his reputation and his advantage in size. In the event it was a major supporter of Johnson, a Thomas Bullock,[4] who gained; he won £20,000 (equivalent to £220,000 as of 2010)[34] from his bets in favour of Johnson and gifted the victor £1,000.[33]

The event was recorded in The Gentleman's Magazine of that month:

... a great boxing match took place ... between two bruisers, Perrins and Johnson: for which a turf stage had been erected 5-foot 6 inches high, and about 40 feet square. The combatants set-to at one in the afternoon; and, after sixty-two rounds of fair and hard fighting, victory was declared in favour of Johnson, exactly at fifteen minutes after two. The number of persons of family and fortune, who interested themselves in this brutal conquest, is astonishing: many of whom, it is proper to add, paid dearly for their diversion.[35]

The contestants received 250 guineas each, with Johnson also receiving two-thirds of the entrance takings (after costs) and Perrins receiving the other third. The net takings were £800, and the number of spectators was variously stated as being 3,000 or 5,000.[19][32][33] Johnson called on Perrins and left him a guinea to buy himself a drink before leaving Banbury.[30] The fight had proved to be "one of the hardest, cleanest and most brilliant encounters that ever took place".[19] As O'Hara put it, "The stevedore at 33 has become at 39 the Croesus of the ring."[16]

Copper medals were struck to commemorate each of the contestants. The obverse side of these contained a picture of the respective fighter; the reverse had the Latin inscription Bella! Horrida bella! (a quotation from Virgil which can be translated as "wars, horrible wars")[36] and the words "Strength and magnanimity" in the case of Perrins, and "Science and intrepidity" for that of Johnson.[37] Chaloner has speculated that these may have been produced by Perrins' employers, Boulton and Watt, and says that they bear similarities with the work of a French die maker called Ponthon who was supplying the firm with industrial items from at least 1791.[32][38] The National Portrait Gallery holds two pictures of the Banbury fight, one an etching published by George Smeeton in 1812,[39] and the other by Joseph Grozer in 1789.[40]

Last fight

Ben Bryan now challenged Johnson once more. He had recovered from his previous illness and won a fight at Banbury against Jacombs, another of the Birmingham challengers, on the day after Johnson's victory against Perrins.[26] Subsequently, Bryan had drawn a 180-round contest with Bill Hooper, also known as "The Tinman", regarding which The Sportsman's Magazine claimed "A more ridiculous match never took place in the annals of pugilism."[18]

The Duke of Hamilton supplied Bryan's stake to fight Johnson in a contest for a prize of 500 guineas held at Wrotham, Kent. Although it is thought that he held property worth £5,000 by the end of the 1780s,[4] and had earned the equivalent of US$125,000[16] in 1789 alone (including money earned from betting on himself), Johnson had to rely on friends to provide his stake because he had spent all of his money. He was a gambling man and an "easy mark", attracting people who gladly took his money from him.[16][41] Brailsford has commented that this dissipation in his personal life was at odds with his cautious, calculated approach when in the prize ring.[4]

Johnson was a clear favourite to win the match, which took place on 17 January 1791 and attracted even more spectators than had been present for the Perrins fight. He had Joe Ward as his second and Mendoza as his bottle holder, with those roles for Bryan being filled by Warr and Humphries. The brutality of the initial fighting was shared by both men. Johnson's nerve failed him, as did his command of the techniques that had served him well. O'Hara describes that he fought "like a wild man" and, throwing caution to the wind, broke a metacarpal in his middle finger after the momentum created by throwing a wild punch caused him to crash into the ring rail and then to the floor. This was the turning point, and O'Hara describes the situation as, "Frightfully beaten, his fists useless, his eyes closed, bathed in blood, and without the chance even of turning the tide with a lucky punch, he refuses to surrender." He had to resort to shifting once more and eventually to wrestling with the hair of Bryan, which generated much disapprobation among the crowd. Eventually Bryan forced Johnson to the floor and beat him unconscious. Johnson had lost the fight, and his status as champion, in 21 minutes. Egan speculated that Johnson's change in style, evident from the outset of the fight might have been due to either genuine concern about Bryan's abilities or from his gambling problems; either way, "there was a miserable falling off in him altogether!"[16][18][41]

Egan wrote that Johnson was the nearest any boxer had come to matching the skill of Jack Broughton.[3] He was thought to have earned more money during his reign as champion than any other fighter until John L. Sullivan almost a century later.[42] Jack Anderson, a modern historian of the sport, has summarised the early boxing writers as agreeing the period of Johnson's reign as champion "rescued the declining sport and heralded the beginning of a golden age".[43]

Life after boxing

Johnson acted as second to various fighters around the period of his rise and fall. He performed this duty for Tom Tyne ("The Tailor") at Croydon on 1 July 1788 and at Horton Moor on 24 March 1790,[44] having previously done so for a fighter called Savage who had taken on Jack Doyle at Stepney Fields on 22 November 1787.[45] He also acted twice for Humphries, in his fights against Mendoza at Odiham on 9 January 1788, when Mendoza sprained his ankle on the slippery surface, and at Stilton on 9 May 1789. There was much controversy at the latter, with O'Hara reporting that this caused Mendoza's second, a Captain Brown, to call Johnson a blackguard; Johnson responded by threatening "to punch Brown into Eternity."[46] Johnson switched fighters and seconded Mendoza against Humphries at Doncaster on 29 September 1790, and again in a contest against Warr near Croydon in May 1792.[47] Similarly, he acted as second for Hooper when he fought George Maddox at Sydenham Common on 10 February 1794[48] and for Tom "Paddington" Jones at Blackheath on 10 May 1794.[49] Other occasions when he acted as second include for John Jackson (near to Croydon, 9 June 1788; and against Mendoza at Hornchurch on 15 April 1795), and Joe Ward (at Hyde Park, date unknown).[50]

After his defeat by Bryan he bought and ran a public house, The Grapes, in Duke Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields, London. Retired prizefighters at that time often received the proceeds of a financial collection from their supporters to enable them to buy a licence to operate such premises: "today's fighter was merely tomorrow's publican in waiting".[51] In a 1901 review of sporting prints titled The old and new pugilism, which lamented the passing of the style and the discipline of prize-fighting, "the goal of the successful pugilist was a sporting public house ... they were generally in side or back streets, where the house did not command a transient trade. Most of these sporting "pubs" had a large room at the back or upstairs, which was open one night a week (preferably Saturday), for public sparring, which was always conducted by a pugilist of some note."[52]

The Grapes soon became known as a haunt of gamblers and criminals, which probably lost Johnson his licence to operate the premises. Subsequently he sought wagers at horse race meetings and cockpits, refusing to pay if he lost and instead challenging the victor to a fight.[4][26] Johnson moved to Copper Alley, Dublin, but had to leave after magistrates determined that his premises were "not proving so consonant to the principles of propriety, as was wished".[41] He then went to Cork, where he tried to earn a living by teaching boxing. Finding that unrewarding he turned once again to gambling, and according to Dennis Brailsford "His deterioration was rapid. Both his health and his spirit were broken". He died in Cork on 21 January 1797, aged 47.[4]

Johnson tutored George Ingleston (The Brewer)[53] and was at least a supporter of Jones, on whom he once bet £100 to win a fight.[54] He also taught a man called Simpson, who went on to fight Jones in 1804.[49]

Johnson's brother, Bill Jackling, also did some boxing. He lost to Elias Spray some time prior to Spray's 1805 fight against Joseph Bourkes, a perennial challenger for the championship.[55]

References

Notes

Citations

- ^ "Pioneer". International Boxing Hall of Fame. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ "Tom Johnson". International Boxing Hall of Fame. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d Egan, Pierce (1830). Boxiana; or, Sketches of ancient and modern pugilism. Vol. 1 (Reprinted ed.). George Virtue. p. 90.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Brailsford, Dennis (2004). "Johnson, Tom (c.1750–1797)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/59099. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c d e Miles's Boy, ed. (26 April 1845). "The history of British boxing from Fig and Broughton to the present time, period II, 1735–1786". The Sportsman's Magazine of Life in London and the Country. 1 (6). London: E. Dipple: 70.

- ^ Thornbury, Walter (1878). "Upper Thames Street (continued)'". Old and New London. Vol. 2. British History Online. pp. 28–41. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ Egan, Pierce (1830). Boxiana; or, Sketches of ancient and modern pugilism. Vol. 1 (Reprinted ed.). George Virtue. pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b Shoemaker, Robert Brink (2004). The London mob: violence and disorder in eighteenth-century England. Continuum International. ISBN 978-1-85285-373-0.

- ^ a b Harvey, Adrian (2004). The beginnings of a commercial sporting culture in Britain, 1793–1850. Ashgate. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-7546-3643-4.

- ^ Kenyon, James W. (1961). Boxing History. Chatham: W & J McKay. p. 11.

- ^ a b c Holt, Richard (1990). Sport and the British: a modern history (New ed.). Clarendon Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 0-19-285229-9.

- ^ Birley, Derek (1993). Sport and the making of Britain. Manchester University Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-7190-3759-7.

- ^ Kenyon, James W. (1961). Boxing History. Chatham: W & J McKay. p. 9.

- ^ a b c d Lynch, Bohun (1922). Knuckles and Gloves. London: W Collins Sons. pp. 7–9. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ Egan, Pierce (1830). Boxiana; or, Sketches of ancient and modern pugilism. Vol. 1 (Reprinted ed.). George Virtue. pp. 258–260, 263.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o O'Hara, Barratt (1909). From Figg to Johnson; a complete history of the heavyweight championship. Chicago, Ill.: The Blossom book bourse. pp. 40–48. hdl:2027/njp.32101019477932.

- ^ a b Egan, Pierce (1830). Boxiana; or, Sketches of ancient and modern pugilism. Vol. 1 (Reprinted ed.). George Virtue. p. 92.

- ^ a b c Miles's Boy, ed. (3 May 1845). "The history of British boxing from Fig and Broughton to the present time, period II, 1735–1786". The Sportsman's Magazine of Life in London and the Country. 1 (7). London: E. Dipple: 83.

- ^ a b c d "Tom Johnson's Greatest Fight". St Joseph Gazette. Vol. 121, no. 44. Missouri. 13 February 1910. p. 26.

- ^ Egan, Pierce (1830). Boxiana; or, Sketches of ancient and modern pugilism. Vol. 1 (Reprinted ed.). George Virtue. pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b c d Miles's Boy, ed. (26 April 1845). "The history of British boxing from Fig and Broughton to the present time, period II, 1735–1786". The Sportsman's Magazine of Life in London and the Country. 1 (6). London: E. Dipple: 71.

- ^ Egan, Pierce (1830). Boxiana; or, Sketches of ancient and modern pugilism. Vol. 1 (Reprinted ed.). George Virtue. p. 117.

- ^ Dowling, Frank L. (1855). Fights for the championship and celebrated prize battles. London: Bell's Life. p. 11.

- ^ Egan, Pierce (1830). Boxiana; or, Sketches of ancient and modern pugilism. Vol. 1 (Reprinted ed.). George Virtue. p. 94.

- ^ a b Egan, Pierce (1830). Boxiana; or, Sketches of ancient and modern pugilism. Vol. 1 (Reprinted ed.). George Virtue. pp. 95–96.

- ^ a b c Miles's Boy, ed. (3 May 1845). "The history of British boxing from Fig and Broughton to the present time, period II, 1735–1786". The Sportsman's Magazine of Life in London and the Country. 1 (7). London: E. Dipple: 82.

- ^ Brailsford, Dennis (1988). Bareknuckles: a social history of boxing. Cambridge: Lutterworth Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-7188-2676-5.

- ^ Harman, Thomas. T. (1885). Showell's Dictionary of Birmingham. Cornish Bros. p. 290.

- ^ a b c Pancratia, or a history of pugilism. London: W. Oxberry. 1812. pp. 89–93. hdl:2027/nyp.33433066623012.

- ^ a b c d Egan, Pierce (1830). Boxiana; or, Sketches of ancient and modern pugilism. Vol. 1 (Reprinted ed.). George Virtue. pp. 97–100.

- ^ Anon. (One of the Fancy) (December 1819). "Boxiana; or sketches of pugilism". Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine. 6: 281–282. hdl:2027/uc1.32106019922423.

- ^ a b c Chaloner, W. H. (October 1973). "Isaac Perrins, 1751–1801, Prize-fighter and Engineer". History Today. 23 (10): 140–143.

- ^ a b c Miles, Henry Downes (1906). Pugilistica: the history of British boxing. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: John Grant. pp. 60–63.

- ^ "Historical UK inflation and price conversion". Safalra. Archived from the original on 30 August 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ^ Sylvanus Urban (pseud.) (October 1789). "Intelligence from Ireland, Scotland and the Country Towns: Country News". The Gentleman's Magazine. 59 (Part 2). London: David Henry: 947–948. hdl:2027/mdp.39015010955006.

- ^ Stone, Jon R. (2005). The Routledge dictionary of Latin quotations: the illiterati's guide to Latin maxims, mottoes, proverbs and sayings. Routledge. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-415-96909-3.

- ^ Heywood, Nathan (1909), "Local and personal medals relating to Manchester", Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society, XXVII: 51–52

- ^ Procter, Richard Wright (1880). Memorials of bygone Manchester. Palmer & Howe. p. 274.

- ^ "Tom Johnson (Thomas Jackling); Isaac Perrins (Smeeton)". London: National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "Tom Johnson (Thomas Jackling); Isaac Perrins (Grozer)". London: National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Egan, Pierce (1830). Boxiana; or, Sketches of ancient and modern pugilism. Vol. 1 (Reprinted ed.). George Virtue. pp. 100–102.

- ^ Menke, Frank Grant (1950). The All-sports record book. A. S. Barnes & Co. p. 81.

- ^ Anderson, Jack (2007). The legality of boxing: a punch drunk love?. Taylor & Francis. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-415-42932-0.

- ^ Egan, Pierce (1830). Boxiana; or, Sketches of ancient and modern pugilism. Vol. 1 (Reprinted ed.). George Virtue. pp. 219–220.

- ^ Egan, Pierce (1830). Boxiana; or, Sketches of ancient and modern pugilism. Vol. 1 (Reprinted ed.). George Virtue. p. 250.

- ^ O'Hara, Barratt (1909). From Figg to Johnson; a complete history of the heavyweight championship. Chicago, Ill.: The Blossom book bourse. pp. 51–54. hdl:2027/njp.32101019477932.

- ^ Miles's Boy, ed. (17 May 1845). "The history of British boxing from Fig and Broughton to the present time, period III, 1786–1798". The Sportsman's Magazine of Life in London and the Country. 1 (9). London: E. Dipple: 106–107.

- ^ Miles's Boy, ed. (28 June 1845). "The history of British boxing from Fig and Broughton to the present time, period III, 1786–1798". The Sportsman's Magazine of Life in London and the Country. 1 (6). London: E. Dipple: 185. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ a b Miles's Boy, ed. (21 June 1845). "The history of British boxing from Fig and Broughton to the present time, period III, 1786–1798". The Sportsman's Magazine of Life in London and the Country. 1 (5). London: E. Dipple: 173.

- ^ Egan, Pierce (1830). Boxiana; or, Sketches of ancient and modern pugilism. Vol. 1 (Reprinted ed.). George Virtue. pp. 291–292, 427.

- ^ Collins, Tony; Vamplew, Wray (2002). Mud, sweat and beers: a cultural history of sport and alcohol. Berg. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-85973-558-9.

- ^ Austin, Alf. (March 1901). "The old and new pugilism". Outing. 37. New York and London: The Outing Publishing Company: 682–687. hdl:2027/mdp.39015050616781.

- ^ Egan, Pierce (1830). Boxiana; or, Sketches of ancient and modern pugilism. Vol. 1 (Reprinted ed.). George Virtue. p. 222.

- ^ Egan, Pierce (1830). Boxiana; or, Sketches of ancient and modern pugilism. Vol. 1 (Reprinted ed.). George Virtue. pp. 229, 232.

- ^ O'Hara, Barratt (1909). From Figg to Johnson; a complete history of the heavyweight championship. Chicago, Ill.: The Blossom book bourse. p. 73. hdl:2027/njp.32101019477932.