Toltec

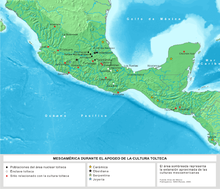

Distribution and influence of the Toltecs in Mesoamerica. | |

| Race | Coyotlatelcas, Chichimeca, Nahuas, Nonoalcas |

|---|---|

| Religion | Toltec Religion |

| Language | Nahuatl, Otomi |

| Geographical range | Mesoamerica (historically) |

| Period | Mesoamerican Postclassic Period |

| Dates | c. 950–1168 |

| Major sites | |

| Preceded by | |

| Followed by | League of Mayapan, Totonacapan, Azcapotzalco, |

| Cause of collapse | Arrival of Chichimec peoples who conquered Tula |

The Toltec culture (/ˈtɒltɛk/) was a pre-Columbian Mesoamerican culture that ruled a state centered in Tula, Hidalgo, Mexico, during the Epiclassic and the early Post-Classic period of Mesoamerican chronology, reaching prominence from 950 to 1150 CE.[1] The later Aztec culture considered the Toltec to be their intellectual and cultural predecessors and described Toltec culture emanating from Tōllān [ˈtoːlːãːn̥] (Nahuatl for Tula) as the epitome of civilization.[2] In the Nahuatl language the word Tōltēkatl [toːɬˈteːkat͡ɬ] (singular) or Tōltēkah [toːɬˈteːkaḁ] (plural) came to take on the meaning "artisan".[3] The Aztec oral and pictographic tradition also described the history of the Toltec Empire, giving lists of rulers and their exploits.

Modern scholars debate whether the Aztec narratives of Toltec history should be given credence as descriptions of actual historical events. While all scholars acknowledge that there is a large mythological part of the narrative, some maintain that, by using a critical comparative method, some level of historicity can be salvaged from the sources. Others maintain that continued analysis of the narratives as sources of factual history is futile and hinders access to learning about the culture of Tula.

Other controversies relating to the Toltec include the question of how best to understand the reasons behind the perceived similarities in architecture and iconography between the archaeological site of Tula and the Maya site of Chichén Itzá. Researchers are yet to reach a consensus in regard to the degree or direction of influence between these two sites.[4]

Origins of society at Tula

While the exact origins of the culture are unclear, it likely developed from a mixture of the Nonoalca people from the southern Gulf Coast and a group of sedentary Chichimeca from northern Mesoamerica. The former of these is believed to have composed the majority of the new culture and were influenced by the Mayan culture.[5] During Teotihuacan's apogee in the Early Classic period, these people were tightly integrated into the political and economic systems of the state and formed large settlements in the Tula region, most notably Villagran and Chingu.[6]

Beginning around 650 CE, the majority of these settlements were abandoned as a result of Teotihuacan's decline. The Coyotlatelco rose as the dominant culture in the region. It is with the Coyotlatelco that Tula, as it relates to the Toltec, was founded along with a number of hilltop communities.[7]

Tula Chico, as the settlement is referred to during this phase, grew into a small regional state out of the consolidation of the surrounding Coyotlatelco sites. The settlement was roughly three to six square kilometers in size with a gridded urban plan and a relatively large population.[8] The complexity of the main plaza was especially distinct from other Coyotlatelco sites in the area, as it had multiple ball courts and pyramids. The Toltec culture, as it is understood during its peak, can be tied directly to Tula Chico; after the site was burned and abandoned at the end of the Epiclassic period, Tula Grande was soon constructed bearing strong similarities 1.5 kilometers to the south.[9] It is during the Early Postclassic period that Tula Grande and its associated Toltec culture would become the dominant force in the broader region.

Archaeology

Some archaeologists, such as Richard Diehl, argue for the existence of a Toltec archaeological horizon characterized by certain stylistic traits associated with Tula, Hidalgo and extending to other cultures and polities in Mesoamerica. Traits associated with this horizon are include the Mixtec-Puebla style[10] of iconography, Tohil plumbate ceramic ware, and Silho or X-Fine Orange Ware ceramics.[11] The presence of stylistic traits associated with Tula in Chichén Itzá is also taken as evidence for a Toltec horizon. The nature of interaction between Tula and Chichén Itzá has been especially controversial, with scholars arguing for either military conquest of Chichén Itzá by the Toltec, Chichén Itzá establishing Tula as a colony, or only loose connections between the two. Whether the Mixteca-Puebla art style has any meaning is also disputed.[12]

A contrary viewpoint is argued in a 2003 study by Michael E. Smith and Lisa Montiel, who compare the archaeological record related to Tula Hidalgo to those of the polities centered in Teotihuacan and Tenochtitlan. They conclude that relative to the influence exerted in Mesoamerica by Teotihuacan and Tenochtitlan, Tula's influence on other cultures was negligible and was probably not deserving of being defined as an empire, but more of a kingdom. While Tula does have the urban complexity expected of an imperial capital, its influence and dominance were not very far reaching.[13] Evidence for Tula's participation in extensive trade networks has been uncovered; for example, the remains of a large obsidian workshop.[14]

Material culture at Tula Grande

At its height, Tula Grande had an estimated population of as many as 60,000 and covered 16 square kilometers of hills, plains, valleys, and marsh.[7] Some of the most prominent examples of the Toltec material culture at the site include pyramids, ball-courts, and the Atlantean warrior sculptures on top of Pyramid B.[15] Various civic buildings surrounding a central plaza are especially distinctive, as excavations show the use of columns inside these buildings and in surrounding colonnades. One of these buildings, known as Building 3, is argued to have been a symbolically powerful building for the Toltec due to its reference in architecture to the historic and mythic homes of the people's ancestors.[16]

The physical layout of the broader plaza also partakes in referencing a shared past; its sunken colonnaded hall units are incredibly similar to those at cities of Tula's ancestral peoples. Importantly, these halls are known to have served as places to engage with both regional and long-distance trade networks and were possibly also used for diplomatic relations, suggesting that Tula Grande used these structures for a similar end. To that point, imported goods at Tula Grande shows that the Toltecs indeed interacted commercially with sites throughout Mesoamerica; shared ceramic and ritual figurine styles between Tula and regions such as Socunusco supplement this idea.[15][7]

Additionally, surveys of Tula Grande have suggested the existence of an "extensive and highly specialized workshop-based obsidian industry," at the site that could have been one of the sources of the city's economic and political power, taking on Teotihuacan's previous role as the region's distributor.[7] A survey done by Healan et al. recovered roughly 16,000 pieces of obsidian from the site's urban zone and over 25,000 from its surrounding residential areas. Tula's involvement in obsidian trade is also evidence for the city's interaction with another powerful city in the region, Chichén Itzá, as the vast majority of obsidian at both sites comes from the same two geological sources.

History of research

One of the earliest historical mentions of Toltecs was in the 16th century by the Dominican friar Diego Durán, who was best known for being one of the first westerners to study the history of Mesoamerica. Durán's work remains relevant to Mesoamerican societies, and based on his findings Durán claims that the Toltecs were disciples of the "High Priest Topiltzin."[17] Topiltzin and his disciples were said to have preached and performed miracles. "Astonished, the people called these men Toltecs," which Duran says, "means Masters, or Men Wise in Some Craft."[18] Duran speculated that this Topilzin may have been the Thomas the Apostle sent to preach the Christian Gospel among the "Indians", although he provides nothing more than circumstantial evidence of any contact between the hemispheres.

The later debate about the nature of the Toltec culture goes back to the late 19th century. Mesoamericanist scholars such as Mariano Veytia, Manuel Orozco y Berra, Charles Etienne Brasseur de Bourbourg, and Francisco Clavigero all read the Aztec chronicles and believed them to be realistic historic descriptions of a pan-Mesoamerican empire based at Tula, Hidalgo.[19] This historicist view was first challenged by Daniel Garrison Brinton who argued that the "Toltecs" as described in the Aztec sources were merely one of several Nahuatl-speaking city-states in the Postclassic period, and not a particularly influential one at that. He attributed the Aztec view of the Toltecs to the "tendency of the human mind to glorify the good old days" and the confounding of the place of Tollan with the myth of the struggle between Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca.[20] Désiré Charnay, the first archaeologist to work at Tula, Hidalgo, defended the historicist views based on his impression of the Toltec capital, and was the first to note similarities in architectural styles between Tula and Chichén Itza. This led him to posit the theory that Chichén Itzá had been violently taken over by a Toltec military force under the leadership of Kukulcan.[21][22] Following Charnay the term Toltec has since been associated with the influx of certain Central Mexican cultural traits into the Maya sphere of dominance that took place in the late Classic and early Postclassic periods; the Postclassic Mayan civilizations of Chichén Itzá, Mayapán and the Guatemalan highlands have been referred to as "Toltecized" or "Mexicanized" Mayas.

The historicist school of thought persisted well into the 20th century, represented in the works of scholars such as David Carrasco, Miguel León-Portilla, Nigel Davies and H. B. Nicholson, which all held the Toltecs to have been an actual ethnic group. This school of thought connected the "Toltecs" to the archaeological site of Tula, which was taken to be the Tollan of Aztec myth.[23] This tradition assumes that much of central Mexico was dominated by a Toltec Empire between the 10th and 12th century AD. The Aztecs referred to several Mexican city states as Tollan, "Place of Reeds", such as "Tollan Cholollan". Archaeologist Laurette Séjourné, followed by the historian Enrique Florescano, have argued that the "original" Tollan was probably Teotihuacán.[24] Florescano adds that the Mayan sources refer to Chichén Itzá when talking about the mythical place Zuyua (Tollan).[citation needed]

Many historicists such as H. B. Nicholson (2001 (1957)) and Nigel Davies (1977) were fully aware that the Aztec chronicles were a mixture of mythical and historical accounts; this led them to try to separate the two by applying a comparative approach to the varying Aztec narratives. For example, they seek to discern between the deity Quetzalcoatl and a Toltec ruler often referred to as Topiltzin Ce Acatl Quetzalcoatl.[4]

Toltecs as myth

Since the 1990s, the historicist position has fallen out of favor for a more critical and interpretive approach to the historicity of the Aztec mythical accounts based on the original approach of Brinton. This approach applies a different understanding of the word Toltec to the interpretation of the Aztec sources, interpreting it as largely a mythical and philosophical construct by either the Aztecs or Mesoamericans generally that served to symbolize the might and sophistication of several civilizations during the Mesoamerican Postclassic period. The Nahuatl word for 'Toltec', for example, can mean 'master artisan' as well as 'inhabitant of Tula, Hidalgo', and the word Tollan (known as Tula in modern times) can refer specifically to Tula, Hidalgo, or more generally to all great cities through meaning 'place of the reeds'.[2]

Much of the questioning of these Aztec narratives is due to the lack of archaeological evidence to support them. Aztec accounts tell that the Toltec discovered medicine, designed the calendar system, created the Nahuatl language. More broadly, the Aztec traced most of their own societal achievements to the Toltec and their city Tollan, which was idolized as the epitome of state civilization with an enormous influence in the surrounding region. However, Tula—the site attributed with this Tollan—lacks much of the splendor that the Aztecs describe. For example, Tula was mainly built out of the relatively soft and unimpressive adobe brick, and while Tula certainly was a major regional city in its time, it was minuscule both in population and in influence in comparison to both its predecessor, Teotihuacan, and its Aztec descendant, Tenochtitlan.[2] Additional material remains at Tula, such as the destruction of Toltec buildings and monumental art coinciding with the arrival of Aztec ceramics, suggest that the Aztecs' reverence of the Toltec might have been mostly propagandistic, intentionally overexaggerating the previous culture to use it as a steppingstone for their own.[2]

Scholars such as Michel Graulich (2002) and Susan D. Gillespie (1989) maintained that the difficulties in salvaging historic data from the Aztec accounts of Toltec history are too great to overcome. For example, there are two supposed Toltec rulers identified with Quetzalcoatl: the first ruler and founder of the Toltec dynasty and the last ruler, who saw the end of the Toltec glory and was forced into humiliation and exile. The first is described as a valiant triumphant warrior, but the last as a feeble and self-doubting old man.[26] This caused Graulich and Gillespie to suggest that the general Aztec cyclical view of time,[citation needed] in which events repeated themselves at the end and beginning of cycles or eras was being inscribed into the historical record by the Aztecs, making it futile to attempt to distinguish between a historical Topiltzin Ce Acatl and a Quetzalcoatl deity.[27] Graulich argued that the Toltec era is best considered the fourth of the five Aztec mythical "Suns" or ages, the one immediately preceding the fifth Sun of the Aztec people, presided over by Quetzalcoatl. This caused Graulich to consider that the only possibly historical data in the Aztec chronicles are the names of some rulers and possibly some of the conquests ascribed to them.[27]

Furthermore, among the Nahuan peoples the word Tolteca was synonymous with artist, artisan or wise man, and Toltecayotl,[14] literally 'Toltecness', meant art, culture, civilization, and urbanism and was seen as the opposite of Chichimecayotl ('Chichimecness'), which symbolized the savage, nomadic state of peoples who had not yet become urbanized.[28] This interpretation argues that any large urban center in Mesoamerica could be referred to as Tollan and its inhabitants as Toltecs – and that it was a common practice among ruling lineages in Postclassic Mesoamerica to strengthen claims to power by asserting Toltec ancestry. Mesoamerican migration accounts often state that Tollan was ruled by Quetzalcoatl (or Kukulkan in Yucatec and Q'uq'umatz in Kʼicheʼ), a godlike mythical figure who was later sent into exile from Tollan and went on to found a new city elsewhere in Mesoamerica. According to Patricia Anawalt, a professor of anthropology at UCLA, assertions of Toltec ancestry and claims that their elite ruling dynasties were founded by Quetzalcoatl have been made by such diverse civilizations as the Aztec, the Kʼicheʼ and the Itza' Mayas.[29]

While the skeptical school of thought does not deny that cultural traits of a seemingly central Mexican origin have diffused into a larger area of Mesoamerica, it tends to ascribe this to the dominance of Teotihuacán in the Classic period and the general diffusion of cultural traits within the region. Recent scholarship, then, does not see Tula, Hidalgo as the capital of the Toltecs of the Aztec accounts. Rather, it takes Toltec to mean simply an inhabitant of Tula during its apogee. Separating the term Toltec from those of the Aztec accounts, it attempts to find archaeological clues to the ethnicity, history and social organization of the inhabitants of Tula.[4]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Smith, Michael Ernest (2012). The Aztecs (3rd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-1-4051-9497-6. OCLC 741355736.

- ^ a b c d Iverson (2017).

- ^ Berit (2015), p. [page needed].

- ^ a b c Smith (2007), p. [page needed].

- ^ Prem, Hanns J. (1997). The ancient Americas: a brief history and guide to research. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. p. 22. ISBN 0-585-13359-X. OCLC 43476754.

- ^ Smith, Michael E.; Diehl, Richard A.; Berlo, Janet Catherine (1993). "Mesoamerica after the Decline of Teotihuacan A. D. 700-900 ". Ethnohistory. 40 (1): 143. doi:10.2307/482182. ISSN 0014-1801.

- ^ a b c d Healan, Dan M.; Cobean, Robert H. (24 September 2012). "Tula and the Toltecs". Oxford Handbooks Online. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195390933.013.0026.

- ^ Smith, Michael E. (1993). "Review of Mesoamerica after the Decline of Teotihuacan A. D. 700-900". Ethnohistory. 40 (1): 143–144. doi:10.2307/482182. ISSN 0014-1801.

- ^ Healan, Dan M.; Cobean, Robert H. (24 September 2012). Tula and the Toltecs. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195390933.013.0026.

- ^ Nicholson (2020), p. [page needed].

- ^ Diehl (1993), p. [page needed].

- ^ Smith & Heath-Smith (1980), p. [page needed].

- ^ Smith & Montiel (2001).

- ^ a b Healan (1989), p. [page needed].

- ^ a b Smith, Michael E. (11 January 2016), "Toltec Empire", The Encyclopedia of Empire, Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–2, retrieved 12 March 2022

- ^ Kowalski, Jeff Karl; Kristin-Graham, Cynthia, eds. (2011). Twin Tollans: Chichén Itzá, Tula, and the epiclassic to early postclassic Mesoamerican world. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. ISBN 978-0-88402-372-2. OCLC 916484803.

- ^ Duran (2010), p. [page needed].

- ^ Duran (1971), p. [page needed].

- ^ Veytia (2000), p. [page needed].

- ^ Brinton (1887), p. [page needed].

- ^ Charnay (1885), p. [page needed].

- ^ Diehl (1993), p. 274.

- ^ Smith (2007), p. [page needed].

- ^ Séjournée (1994), p. [page needed].

- ^ "Eagle Relief, Toltec". Metropolitan Museum of Art website.

- ^ Gillespie (1989), p. [page needed].

- ^ a b Graulich (2002), p. [page needed].

- ^ Morritt (2011), p. [page needed].

- ^ Anawalt (1990).

Works cited

- Anawalt, Patricia Rieff (1990). "The Emperors' Cloak: Aztec Pomp, Toltec Circumstances". American Antiquity. 55 (2): 291–307. doi:10.2307/281648. JSTOR 281648.

- Berit, Ase (2015). Lifelines in World History: The Ancient World, The Medieval World, The Early Modern World, The Modern World. Routledge.

- Brinton, Daniel Garrison (1887). "Were the Toltecs an Historic Nationality?". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 24 (126): 229–241. JSTOR 983071.

- Charnay, Desiré (1885). "La Civilisation Tolteque". Revue d'Ethnographie. iv: 281.

- Davies, Nigel (1977). The Toltecs: Until the Fall of Tula. Civilization of the American Indian series, Vol. 153. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1394-4.

- Diehl, Richard A. (1993). "The toltec Horizon in Mesoamerica: New perspectives on an old issue". In Don Stephen Rice (ed.). Latin American horizons: a symposium at Dumbarton Oaks, 11th and 12th October 1986. Dumbarton Oaks.

- Duran, Diego (1971) [ca. 1574-76]. Book of the Gods and Rites and the Ancient Calendar. Translated by Doris Heyden and Fernando Horcasitas. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, Publishing Division of the University. pp. 57–69. ISBN 0-8061-0889-4.

- Duran, Diego (2010) [ca. 1574-76]. The History of the Indies of New Spain. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, Publishing Division of the University.

- Florescano, Enrique (1999). The Myth of Quetzalcoatl [El mito de Quetzalcóatl]. Translated by Lysa Hochroth. Raúl Velázquez (illus.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7101-8. OCLC 39313429.

- Gillespie, Susan D. (1989). The Aztec Kings: The Construction of Rulership in Mexica History. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-1095-4. OCLC 60131674.

- Graulich, Michel (2002). "Los reyes de Tollan". Revista Española de Antropología Americana (in Spanish). 32: 87–114.

- Healan, Dan M. (1989). Tula of the Toltecs: Excavations and Survey. University of Iowa Press.

- Iverson, Shannon Dugan (1 March 2017). "The Enduring Toltecs: History and Truth During the Aztec-to-Colonial Transition at Tula, Hidalgo". Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 24 (1): 90–116. doi:10.1007/s10816-017-9316-4. ISSN 1573-7764. OCLC 1188163515.

- Morritt, Robert D. (2011). Olde New Mexico. New Castle: Cambridge Scholars.

- Nicholson, H. B. (2020). "Mixteca–Puebla". oxfordartonline.com. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T058690. Archived from the original on 4 June 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- Séjournée, Laurette (1994). Teotihuacan, capital de los Toltecas (in Spanish). Mexico, DF: Siglo Veintiuno Editores.

- Smith, Michael E.; Heath-Smith, Cynthia (1980). "Waves of Influence in Postclassic Mesoamerica? A Critique of the Mixteca-Puebla Concept" (PDF). Anthropology. 4 (2): 15–50.

- Smith, Michael E.; Montiel, Lisa M. (2001). "The Archaeological Study of Empires and Imperialism in Prehispanic Central Mexico". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 20 (3): 245–284. doi:10.1006/jaar.2000.0372.

- Smith, Michael E. (2007). "Tula and Chichén Itzá: Are We Asking the Right Questions?". In Kowalski, Jeff Karl; Kristin-Graham, Cynthia (eds.). Twin Tollans: Chichén Itzá, Tula, and the Epiclassic to Early Postclassic Mesoamerican World. Washington DC: Dumbarton Oaks. pp. 579–617.

- Veytia, Mariano (2000) [1836]. Hemingway, Donald W.; Hemingway, W. David (eds.). Ancient America Rediscovered [Historia antigua de Mexico, book 1, ch. 1-23]. Translated by Ronda Cunningham (1st English ed.). Springville, UT: Bonneville Books. ISBN 1-55517-479-5. OCLC 45203586.

Further reading

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1876). The Native Races of the Pacific States of North America: Primitive History. Vol. 5. D. Appleton.

- Carrasco, David (1982). Quetzalcoatl and the Irony of Empire: Myths and Prophecies in the Aztec Tradition. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-09487-1. OCLC 0226094871.

- Davies, Nigel (1980). The Toltec Heritage: From the Fall of Tula to the Rise of Tenochtitlan. Civilization of the American Indian series, Vol. 153. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1505-X. OCLC 5103377.

- de Sahagún, Bernardino (1950–1982) [ca. 1540–85]. Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain, 13 vols. in 12. vols. I-XII. Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J.O. Anderson (eds., trans., notes and illus.) (translation of Historia General de las Cosas de la Nueva España ed.). Santa Fe, NM and Salt Lake City: School of American Research and the University of Utah Press. ISBN 0-87480-082-X. OCLC 276351.

- Diehl, Richard A. (1983). Tula: The Toltec Capital of Ancient Mexico. New York: Thames & Hudson.

- Kirchhoff, Paul (1985). "El imperio tolteca y su caída.". In Jesús Monjarás-Ruiz; Rosa Brambila; Emma Pérez-Rocha (eds.). Mesoamérica y el centro de México: Una antología. Mexico City: Instituo Nacional de Antropología e Historia. pp. 249–272. ISBN 978-968-6038-26-2.

- Miller, Mary; Karl Taube (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya: An Illustrated Dictionary of Mesoamerican Religion. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05068-6. OCLC 27667317.

- Ringle, William M.; Tomás Gallareta Negrón; George J. Bey (1998). "The Return of Quetzalcoatl". Ancient Mesoamerica. 9 (2). Cambridge University Press: 183–232. doi:10.1017/S0956536100001954.

- Smith, Michael E. (1984). "The Aztlan Migrations of Nahuatl Chronicles: Myth or History?" (PDF online facsimile). Ethnohistory. 31 (3). Columbus, OH: American Society for Ethnohistory: 153–186. doi:10.2307/482619. ISSN 0014-1801. JSTOR 482619. OCLC 145142543.

External links

Media related to Toltec at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Toltec at Wikimedia Commons