Tiriel

Tiriel is a narrative poem by William Blake, written c.1789. Considered the first of his prophetic books, it is also the first poem in which Blake used free septenaries, which he would go on to use in much of his later verse. Tiriel was unpublished during Blake's lifetime and remained so until 1874, when it appeared in William Michael Rossetti's Poetical Works of William Blake.[1] Although Blake did not engrave the poem, he did make twelve sepia drawings to accompany the rough and unfinished manuscript. However, three of them are considered lost as they have not been traced since 1863.[2]

Synopsis

Many years before the poem begins, the sons of Har and Heva revolted and abandoned their parents. Tiriel subsequently set himself up as a tyrant in the west, driving one of his brothers, Ijim, into exile in the wilderness, and chaining the other, Zazel, in a cave in the mountains. Tiriel then made slaves of his own children, until eventually, led by the eldest son, Heuxos, they too rebelled, overthrowing their father. Upon his demise, Tiriel refused their offer of refuge in the palace and instead went into exile in the mountains with his wife, Myratana. Five years later, the poem begins with the now blind Tiriel returning to the kingdom with his dying wife, as he wants his children to see her death, believing them to be responsible and cursing them for betraying him five years previously; "Come you accursed sons./In my weak arms. I here have borne your dying mother/Come forth sons of the Curse come forth. see the death of Myratana" (1:7-9).[3] Soon thereafter, Myratana dies, and Tiriel's children again ask him to remain with them but he refuses and wanders away, again cursing them and telling them he will have his revenge;

There take the body. cursed sons. & may the heavens rain wrath

As thick as northern fogs. around your gates. to choke you up

That you may lie as now your mother lies. like dogs. cast out

The stink. of your dead carcases. annoying man & beast

Till your white bones are bleachd with age for a memorial.

No your remembrance shall perish. for when your carcases

Lie stinking on the earth. the buriers shall arise from the east

And. not a bone of all the soils of Tiriel remain

Bury your mother but you cannot bury the curse of Tiriel[4]— 1:42-50

After some time wandering, Tiriel eventually arrives at the "pleasant gardens" (2:10) of the Vales of Har, where he finds his parents, Har and Heva. However, they have both become senile and have regressed to a childlike state to such an extent that they think their guardian, Mnetha, is their mother. Tiriel lies about who he is, claiming that he was cast into exile by the gods, who then destroyed his race; "I am an aged wanderer once father of a race/Far in the north. but they were wicked & were all destroyd/And I their father sent an outcast" (2:44-46). Excited by the visit, Har and Heva invite Tiriel to help them catch birds and listen to Har's singing in the "great cage" (3:21). Tiriel refuses to stay, however, claiming his journey is not yet at an end, and resumes his wandering.

He travels into the forest and soon encounters his brother Ijim, who has recently been terrorised by a shapeshifting spirit to whom he refers to as "the Hypocrite". Upon seeing Tiriel, Ijim immediately assumes that Tiriel is another manifestation of the spirit;

This is the hypocrite that sometimes roars a dreadful lion

Then I have rent his limbs & left him rotting in the forest

For birds to eat but I have scarce departed from the place

But like a tyger he would come & so I rent him too

Then like a river he would seek to drown me in his waves

But soon I buffetted the torrent anon like to a cloud

Fraught with the swords of lightning. but I bravd the vengeance too

Then he would creep like a bright serpent till around my neck

While I was Sleeping he would twine I squeezd his poisnous soul

Then like a toad or like a newt. would whisper in my ears

Or like a rock stood in my way. or like a poisnous shrub

At last I caught him in the form of Tiriel blind & old[5]— 4:49-60

Tiriel assures Ijim that he is, in fact, the real Tiriel, but Ijim does not believe him and decides to return to Tiriel's palace to see the real Tiriel and thus expose the spirit as an imposter; "Impudent fiend said Ijim hold thy glib & eloquent tongue/Tiriel is a king. & thou the tempter of dark Ijim" (4:36-37). However, upon arriving at the palace, Heuxos informs Ijim that the Tiriel with him is indeed the real Tiriel, but Ijim suspects that the entire palace and everyone in it is part of the spirit's deception; "Then it is true Heuxos that thou hast turnd thy aged parent/To be the sport of wintry winds. (said Ijim) is this true/It is a lie & I am like the tree torn by the wind/Thou eyeless fiend. & you dissemblers. Is this Tiriels house/It is as false as Matha. & as dark as vacant Orcus/Escape ye fiends for Ijim will not lift his hand against ye" (4:72-77). As such, Ijim leaves, and upon his departure, Tiriel, descending ever more rapidly into madness, curses his children even more passionately than before;

Earth thus I stamp thy bosom rouse the earthquake from his den

To raise his dark & burning visage thro the cleaving ground

To thrust these towers with his shoulders. let his fiery dogs

Rise from the center belching flames & roarings. dark smoke

Where art thou Pestilence that bathest in fogs & standing lakes

Rise up thy sluggish limbs. & let the loathsomest of poisons

Drop from thy garments as thou walkest. wrapt in yellow clouds

Here take thy seat. in this wide court. let it be strown with dead

And sit & smile upon these cursed sons of Tiriel

Thunder & fire & pestilence. here you not Tiriels curse[6]— 5:4-13

Upon this declamation, four of his five daughters and one hundred of his one hundred and thirty sons are destroyed, including Heuxos. Tiriel then demands that his youngest and only surviving daughter, Hela, lead him back to the Vales of Har. She reluctantly agrees, but on the journey, she denounces him for his actions; "Silence thy evil tongue thou murderer of thy helpless children" (6:35). Tiriel responds in a rage, turning her locks of hair into snakes, although he vows that if she brings him to the Vales of Har, he will return her hair to normal. On the way through the mountains, as they pass the cave wherein lives Zazel and his sons, Hela's cries of lamentation awaken them, and they hurl dirt and stones at Tiriel and Hela, mocking them as they pass; "Thy crown is bald old man. The sun will dry thy brains away/And thou wilt be as foolish as thy foolish brother Zazel" (7:12-13). Eventually, Tiriel and Hela reach the Vales of Har, but rather than celebrating his return, Tiriel condemns his parents, and the way they brought him up, declaring that his father's laws and his own wisdom now "end together in a curse" (8:8);

The child springs from the womb. the father ready stands to form

The infant head while the mother idle plays with her dog on her couch

The young bosom is cold for lack of mothers nourishment & milk

Is cut off from the weeping mouth with difficulty & pain

The little lids are lifted & the little nostrils opend

The father forms a whip to rouze the sluggish senses to act

And scourges off all youthful fancies from the newborn man

Then walks the weak infant in sorrow compelld to number footsteps

Upon the sand. &c

And when the drone has reachd his crawling length

Black berries appear that poison all around him. Such was Tiriel

Compelld to pray repugnant & to humble the immortal spirit

Till I am subtil as a serpent in a paradise

Consuming all both flowers & fruits insects & warbling birds

And now my paradise is falln & a drear sandy plain

Returns my thirsty hissings in a curse on thee O Har

Mistaken father of a lawless race my voice is past[7]— 8:12-28

Upon this outburst, Tiriel then dies at his parents' feet; "He ceast outstretch'd at Har & Heva's feet in awful death" (8:29).

Characters

- Tiriel – as the former king of the west, Tiriel is of the body in Blake's mythological system, in which the west is assigned to Tharmas, representative of the senses. However, when he visits the Vales of Har, Tiriel falsely claims to be from the north, which is assigned to Urthona, representative of the imagination.[1] Most scholars agree that Tiriel's name was probably taken from Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa's De occulta philosophia libri tres (1651), where the name is associated with the planet Mercury and the elements sulphur and mercury.[8] Harold Bloom, however, believes the name is a combination of the word 'tyrant' and the Hebrew word for God, El.[9] In terms of Tiriel's character, David V. Erdman believes that he is partially based on King George III, who suffered bouts of insanity throughout 1788 and 1789. Erdman argues that "the pattern of Tiriel's "madness and deep dismay" parallels that of King George's,"[10] and thus the poem is "a symbolic portrait of the ruler of the British Empire. [Blake] knew that the monarch who represented the father principal of law and civil authority was currently insane."[11] As evidence, Erdman points out that during his bouts of insanity, George tended to become hysterical in the presence of four of his five daughters, only the youngest, (Amelia), could calm him (in the poem, Tiriel destroys four of his daughters but spares the youngest, his favourite).[12] Bloom believes that Tiriel is also partially based on William Shakespeare's King Lear and, in addition, is a satire "of the Jehovah of deistic orthodoxy, irascible and insanely rationalistic."[13] Northrop Frye makes a similar claim; "He expects and loudly demands gratitude and reverence from his children because he wants to be worshipped as a god, and when his demands are answered by contempt he responds with a steady outpouring of curses. The kind of god which the existence of such tyrannical papas suggests is the jealous Jehovah of the Old Testament who is equally fertile in curses and pretexts for destroying his innumerable objects of hatred."[14] Alicia Ostriker believes the character to be partially based on both Oedipus from Sophocles' Oedipus Rex and the prince of Tyre from the Book of Ezekiel (28:1-10), who is denounced by Ezekiel for trying to pass himself off as God.[8] Looking at the character from a symbolic point of view, Frye argues that he "symbolises a society or civilisation in its decline."[15]

- Har – Mary S. Hall believes that Har's name was derived from Jacob Bryant's A New System or Analysis of Antient Mythology (1776), where Bryant conflates the Amazonian deities Harmon and Ares with the Egyptian deity Harmonia, wife of Cadmus. Blake had engraved plates for the book in the early 1780s, so he would certainly have been familiar with its content.[16] As a character, S. Foster Damon believes that Har represents both the "decadent poetry of Blake's day"[17] and the traditional spirit of Christianity.[1] Northrop Frye reaches a similar conclusion but also sees divergence in the character, arguing that although Har and Heva are based on Adam and Eve, "Har is distinguished from Adam. Adam is ordinary man in his mixed twofold nature of imagination and Selfhood. Har is the human Selfhood which, though men spend most of their time trying to express it, never achieves reality and is identified only as death. Har, unlike Adam, never outgrows his garden but remains there shut up from the world in a permanent state of near-existence."[14] Bloom agrees with this interpretation, arguing that "Har is natural man, the isolated selfhood." Bloom also believes that Har is comparable to Struldbruggs from Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726) and Tithonus from Alfred, Lord Tennyson's poem of the same name (1859).[13] In another sense, Frye suggests that "Har represents the unborn theory of negative innocence established by obeying a moral law."[15] On the other hand, Anne Kostelanetz Mellor sees Har as representing simple innocence and the Vales of Har as representative of Eden.[18] 'Har' is the Hebrew word for 'mountain', thus giving an inherent irony to the phrase "Vales of Har". Damon believes this conveys the ironic sense that "he who was a mountain now lives in a vale, cut off from mankind.[17]

- Heva – Frye believes she is "a reduplicate Eve."[14] Damon argues that she represents neoclassical painting.[1]

- Ijim – Ostriker feels he represents superstition.[19] Damon believes he represents the power of the common people.[20] Ijim's name could have come from Emanuel Swedenborg's Vera Christiana Religio (1857);[14] "the ochim, tziim and jiim, which are mentioned in the prophetical parts of the Word." In the poem, Ijim encounters a tiger, a lion, a river, a cloud, a serpent, a toad, a rock, a shrub and Tiriel. In Swedenborg, "self-love causes its lusts to appear at a distance in hell where it reigns like various species of wild beasts, some like foxes and leopards, some like wolves and tigers, and some like crocodiles and venomous serpents." The word is also found in the Book of Isaiah 13:21, where it is translated as "satyrs".[20] According to Harold Bloom, "The Ijim are satyrs or wild men who will dance in the ruins of the fallen tyranny, Babylon. Blake's Ijim is a self-brutalised wanderer in a deathly nature [...] The animistic superstitions of Ijim are a popular support for the negative holiness of Tiriel."[13] On the other hand, W.H. Stevenson reads Ijim as "an old-fashioned Puritan – honest but grim, always a ready adversary of Sin."[21] Nancy Bogen believes he may be partially based on William Pitt, especially his actions during the Regency Crisis of 1788.[22]

- Zazel – Damon argues that Zazel represents the outcast genius.[20] As with Tiriel, his name was probably taken from Agrippa, where it is associated with Saturn and the element earth.[23] The name could also be a modification of the Hebrew word Azazel, which occurs in the Book of Leviticus, 16:10, and tends to be translated as "scapegoat".[24] Nancy Bogen believes he may be partially based on the Whig politician Charles James Fox, archrival of William Pitt.[22]

- Myratana – her name may have come from Myrina, Queen of Mauretania, who was described in Bryant's A New System.[25]

- Heuxos – Hall believes the name was derived from the Hyksos, an Asiatic people who invaded the Nile Delta in the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt c.1720 BC.[26]

- Yuva – son of Tiriel

- Lotho – son of Tiriel

- Hela – Damon argues that she symbolises touch and sexuality.[20] She is possibly named after Hel, the Scandinavian goddess of Hell in Thomas Gray's "The Descent of Odin" (1768).[19]

- Mnetha – Damon believes she represents the spirit of neoclassicism, which Blake felt encouraged inferior poetry and painting.[1] He also points out that Mnetha is "almost" an anagram of Athena, goddess of wisdom. Frye suggests that the name is an amalgamation of Athena and Mnemosyne, the personification of memory in Greek mythology.[27] Anne Kostelanetz Mellor sees her as representative of "that memory that preserves the vision of the past."[28]

- Clithyma and Makuth – sons of Tiriel mentioned in a deleted passage

- Four unnamed daughters and one hundred and twenty-five unnamed sons

Manuscript

Tiriel survives in only a single manuscript copy, located in the British Museum. An eight-page document written in Blake's hand, the manuscript is inscribed "Tiriel / MS. by Mr Blake". It is believed that up to page 8, line 4 ("Lead me to Har & Heva I am Tiriel King of the west"), the poem is a fair copy, transcribed from somewhere else, but at 8:4 the number of corrections and alterations increases, and the writing becomes scribbled and in a different ink to the rest of the poem. This difference has led Erdman to argue that the later part of the poem was not transcribed, but was worked out in the manuscript itself, and may have been rushed. Additionally, many of the handwritten corrections, emendations and deletions in the parts of the poem prior to 8:4 are in the same ink as the lines after 8:4, suggesting Blake went back over the manuscript and revised earlier parts of it when he returned to finish it.[29]

A considerable amount of material has been deleted by Blake in the manuscript.[30] For example, when Tiriel initially arrives in the Vales of Har, he lies about his identity. In the poem as Blake left it, the scene reads "I am not of this region, said Tiriel dissemblingly/I am an aged wanderer once father of a race/Far in the north" (2:43-44). However, in the original manuscript, between these two lines is contained the line "Fearing to tell them who he was, because of the weakness of Har." Similarly, when Har recognises Tiriel he proclaims "Bless thy face for thou are Tiriel" (3:6), to which Tiriel responds "Tiriel I never saw but once I sat with him and ate" (3:7). Between these two lines were originally the lines "Tiriel could scarcely dissemble more & his tongue could scarce refrain/But still he fear'd that Har & Heva would die of joy and grief."

The longest omissions occur during the encounter with Ijim and when Tiriel returns to the Vales of Har. When Ijim arrives at the palace with Tiriel, he begins by saying "Then it is true Heuxos that thou hast turned thy aged parent/To be the sport of wintry winds" (4:72-73). However, originally, Ijim begins,

Lotho. Clithyma. Makuth fetch your father

Why do you stand confounded thus. Heuxos why art thou silent

O noble Ijim thou hast brought our father to our eyes

That we may tremble & repent before thy mighty knees

O we are but the slaves of Fortune. & that most cruel man

Desires our deaths. O Ijim if the eloquent voice of Tiriel

Hath workd our ruin we submit nor strive against stern fate

He spoke & kneeld upon his knee. Then Ijim on the pavement

Set aged Tiriel. in deep thought whether these things were so[31]

The second large deletion occurs towards the end of the poem, when Tiriel asks Har "Why is one law given to the lion & the patient Ox/And why men bound beneath the heavens in a reptile form" (8:9-10). Originally, however, between these two lines was

Dost thou not see that men cannot be formed all alike

Some nostrild wide breathing out blood. Some close shut up

In silent deceit. poisons inhaling from the morning rose

With daggers hid beneath their lips & poison in their tongue

Or eyed with little sparks of Hell or with infernal brands

Flinging flames of discontent & plagues of dark despair

Or those whose mouths are graves whose teeth the gates of eternal death

Can wisdom be put in a silver rod or love in a golden bowl

Is the son of a king warmed without wool or does he cry with a voice

Of thunder does he look upon the sun & laugh or stretch

His little hands into the depths of the sea, to bring forth

The deadly cunning of the flatterer & spread it to the morning[32]

A major question concerning the manuscript is whether or not Blake ever intended to illuminate it. Whether he had devised his method for relief etching at the time of composition is unknown, although he did make twelve drawings which were apparently to be included with the poem in some shape or form. Peter Ackroyd suggests that the illustrations, "conceived in the heroic style," were inspired by the work of James Barry and George Romney, both of whom Blake admired and were intended for illustration rather than illumination.[33] Most scholars agree with this theory (i.e. the images wouldn't be combined with the text, they would simply accompany the text) and it has been suggested that Blake abandoned the project when he discovered the technique to realise his desire for full integration of text and image.[1] His first relief etching was The Approach of Doom (1788), and his first successful combination of words and pictures were All Religions are One and There is No Natural Religion (both 1788), but they were experiments only.[34] His first 'real' illuminated book was The Book of Thel (1789) and it is possible that he abandoned Tiriel to work on Thel after making his breakthrough with All Religions and Natural Religion. According to David Bindman, for example, "Tiriel's clear separation of text and design is transitional in being an example of the conventional method of combining text with design implicitly rejected by Blake in developing the method of illuminated printing. He probably abandoned the series because his new technique took him beyond what had now become for him an obsolete method."[35]

Blake's mythology

Although Blake had yet to formulate his mythological system, several preliminary elements of that system are present in microcosm in Tiriel. According to Peter Ackroyd, "the elements of Blake's unique mythology have already begun to emerge. It is the primeval world of Bryant and of Stukeley, which he had glimpsed within engravings of stones and broken pillars."[33] Elements of his later mythology are thus manifested throughout the poem.

Although Northrop Frye speculates that the Vales of Har are located in Ethiopia,[14] due to the pyramids in the illustration Tiriel supporting Myratana, S. Foster Damon believes the poem to be set in Egypt, which is a symbol of slavery and oppression throughout Blake's work.[20] For example, in The Book of Urizen (1794), after the creation of mortal man,

They lived a period of years

Then left a noisom body

To the jaws of devouring darkness

And their children wept, & built

Tombs in the desolate places,

And form'd laws of prudence, and call'd them

The eternal laws of God

And the thirty cities remaind

Surrounded by salt floods, now call'd

Africa: its name was then Egypt.

The remaining sons of Urizen

Beheld their brethren shrink together

Beneath the Net of Urizen;

Perswasion was in vain;

For the ears of the inhabitants,

Were wither'd, & deafen'd, & cold:

And their eyes could not discern,

Their brethren of other cities.

So Fuzon call'd all together

The remaining children of Urizen:

And they left the pendulous earth:

They called it Egypt, & left it.[36]— Chap: IX, stanzas 4-8 (Plate 28, lines 1-22)

Similarly, in The Book of Los (1795), Urizen is imprisoned within "Coldness, darkness, obstruction, a Solid/Without fluctuation, hard as adamant/Black as marble of Egypt; impenetrable" (Chap. I, Verse 10). Many years later, in On Virgil (1822), Blake claims that "Sacred Truth has pronounced that Greece & Rome as Babylon & Egypt: so far from being parents of Arts & Sciences as they pretend: were destroyers of all Art." Similarly, in The Laocoön (also 1822), he writes "The Gods of Greece & Egypt were Mathematical Diagrams," "These are not the Works/Of Egypt nor Babylon Whose Gods are the Powers of this World. Goddess, Nature./Who first spoil & then destroy Imaginative Art For their Glory is War and Dominion" and "Israel delivered from Egypt is Art delivered from Nature & Imitation."

Another connection to Blake's later mythology is found in The Vales of Har, which are mentioned in The Book of Thel (1789). It is in the Vales where lives Thel herself, and throughout the poem, they are represented as a place of purity and innocence; "I walk through the vales of Har. and smell the sweetest flowers" (3:18). At the end of the poem, when Thel is shown the world of experience outside the Vales, she panics and flees back to the safety of her home; "The Virgin started from her seat, & with a shriek./Fled back unhinderd till she came into the vales of Har" (6:21-22).

The characters of Har and Heva also reappear in the Africa section of The Song of Los (1795), which is set chronologically before Tiriel. Disturbed by the actions of their family, Har and Heva flee into the wilderness, and turn into reptiles;

Since that dread day when Har and Heva fled.

Because their brethren & sisters liv'd in War & Lust;

And as they fled they shrunk

Into two narrow doleful forms:

Creeping in reptile flesh upon

The bosom of the ground:[37]— The Song of Los; Plate 4, lines 4-9

Damon refers to this transformation as turning them into "serpents of materialism," which he relates back to their role in Tiriel.[17]

Har and Ijim are also briefly mentioned in Vala, or The Four Zoas (1796–1803), where Har is the sixteenth son of Los and Enitharmon, and Ijim the eighteenth. Har's immediate father is Satan, representative of self-love in Blake, and his children are Ijim and Ochim (The Four Zoas, VIII:360).

Although Tiriel himself is not featured in any of Blake's later work, he is often seen as a foreshadowing of Urizen, limiter of men's desires, embodiment of tradition and conformity, and a central character in Blake's mythology, appearing in Visions of the Daughters of Albion (1793), America a Prophecy (1793), Europe a Prophecy (1794), The Book of Urizen (1794), The Book of Ahania (1795), The Book of Los (1795), The Song of Los (1795), Vala, or The Four Zoas (1796–1803), Milton a Poem (1804–1810), and Jerusalem The Emanation of the Giant Albion (1804–1820). Tiriel is similar to Urizen insofar as "he too revolted, set himself up as a tyrant, became a hypocrite, ruined his children by his curse, and finally collapsed."[38]

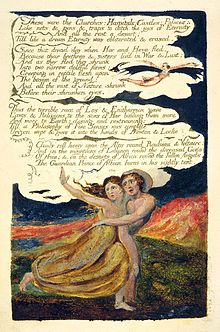

Other aspects of Blake's mythology also begin to emerge during the poem. For example, Damon argues that the death of the four unnamed daughters and the corruption of the fifth is Blake's first presentation of the death of the four senses and the corruption of touch, or sex; "all imaginative activity based on the senses disappears except automatic sexual reproduction. Even this proves too much for his moral virtue."[39] As Damon elaborates, "Hela's Medusan locks are the torturing thoughts of suppressed lust."[40] The corruption of the senses plays an important role throughout Europe a Prophecy ("the five senses whelm'd/In deluge o'er the earth-born man"), The Book of Urizen ("The senses inwards rush'd shrinking,/Beneath the dark net of infection"), The Song of Los ("Thus the terrible race of Los & Enitharmon gave/Laws & Religions to the sons of Har binding them more/And more to Earth: closing and restraining:/Till a Philosophy of Five Senses was complete"), The Four Zoas ("Beyond the bounds of their own self their senses cannot penetrate") and Jerusalem ("As the Senses of Men shrink together under the Knife of flint").

Harold Bloom points out that the points of the compass, which would come to play a vital role in Blake's later mythological system, are used symbolically for the first time in Tiriel; "the reference to "the western plains" in line 2 marks the onset of Blake's directional system, in which the west stands for man's body, with its potential either for sensual salvation or natural decay."[13] In The Four Zoas, Milton and Jerusalem, after the Fall of the primeval man, Albion, he is divided fourfold, and each of the four Zoas corresponds to a point on the compass and an aspect of Fallen man; Tharmas is west (the body), Urizen is south (Reason), Luvah is east (emotions) and Urthona is north (imagination).

Another subtle connection with the later mythological system is found when Tiriel has all but thirty of his sons killed; "And all the children in their beds were cut off in one night/Thirty of Tiriels sons remaind. to wither in the palace/Desolate. Loathed. Dumb Astonishd waiting for black death" (5:32-34). Damon believes this foreshadows The Book of Urizen, where Urizen brings about the fall of the thirty cities of Africa; "And their thirty cities divided/In form of a human heart", "And the thirty cities remaind/Surrounded by salt floods" (27:21-22 and 28:8-9).

Another minor connection to the later mythology is that two lines from the poem are used in later work by Blake. The deleted line "can wisdom be put in a silver rod, or love in a golden bowl?" is found in the Motto from The Book of Thel, and a version of the line "Why is one law given to the lion & the patient Ox?" (8:9) is found as the final line of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790); "One Law for the Lion & Ox is Oppression."

Critical interpretations

Tiriel has provoked a number of divergent critical responses. For example, according to G.E. Bentley, "Tiriel has always proved a puzzle to commentators on Blake."[2] Similarly, Kathleen Raine points out, "this phantasmagoria on the theme of the death of an aged king and tyrant-father may be – indeed, must be – read at several levels."[41] Making much the same point, W.H. Stevenson argues that "the theme is not clearly related to any political, philosophical, religious or moral doctrine."[42]

Northrop Frye reads the poem symbolically, seeing it primarily as "a tragedy of reason,"[14] and arguing that "Tiriel is the puritanical iconoclasm and brutalised morality that marks the beginning of cultural decadence of which the lassitude of Deism is the next stage, and Ijim is introduced to show the mental affinity between Deism and savagery."[43]

A different reading is given by S. Foster Damon, who argues that it is "an analysis of the decay and failure of Materialism at the end of the Age of Reason."[1] Similarly, arguing that Har represents Christianity and Heva is an Eve figure, Damon believes the poem illustrates that "by the end of the Age of Reason, official religion had sunk into the imbecility of childhood."[17]

David V. Erdman looks at the poem from a political perspective, reading it in the light of the commencement of the French Revolution in July 1789, with the Storming of the Bastille. He believes the poem deals both with pre-revolutionary France and "unrevolutionary" England, where people were more concerned with the recently revealed madness of George III than with righting the wrongs of society, as Blake saw them; "in France the people in motion were compelling the King to relax his grasp on the spectre. In England, the royal grasp had suddenly failed but there seemed nothing for the people to do but wait and see [...] when the King's recovery was celebrated, a bit prematurely, in March 1789, "happiness" was again official. Popular movements did exist, but except for the almost subterranean strike of the London blacksmiths for a shorter workday, they were largely humanitarian or pious in orientation and in no immediate sense revolutionary."[44] He also feels the poem deals with "the internal disintegration of despotism,"[45] and finds a political motive in Tiriel's final speech, which he sees as inspired by Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Emile, or On Education.[46]

Anne Kostelanetz Mellor also reads the poem as a political tract, although from a very different perspective than Erdman. She argues that the poem engages with "Blake's increasing uncertainty about both the social and the aesthetic implications of a closed form or system"[47] and concludes with the edict that Tiriel's "repressive reign of deceit, slander, discontent and despair enslaves not only the ruled but the ruler as well [...] his closed mind, chained to closed palaces and legal systems ends by destroying both itself and everything over which it gains power.[48] In this sense, she reads Tiriel's final speech as "reflecting the agony of a self trapped in the repressive social mores and intellectual absolutism of eighteenth-century England."[49]

Harold Bloom, however, is not convinced of a political interpretation, arguing instead that "Tiriel's failure to learn until too late the limitations of his self-proclaimed holiness is as much a failure in a conception of divinity as it is of political authority."[13]

Another theory is suggested by Peter Ackroyd, who argues that the poem is "a fable of familial blindness and foolishness – fathers against sons, brother against brother, a family dispersed and alienated – which concludes with Blake's belief in the spiritual rather than the natural, man."[33]

Alicia Ostriker believes that the poem deals with "the failure of natural law."[19]

Perhaps the most common theory, however, is summarised by Nelson Hilton, who argues that it "suggests in part a commentary on the state of the arts in an age which could conceive of poetry as a golden structure built with "harmony of words, harmony of numbers" (John Dryden) [...] exchanging the present for the past, Tiriel views late eighteenth-century English artistic material and practice as an impotent enterprise with nothing left but to curse its stultifying ethos of decorum and improvement."[50] Hilton is here building on the work of Damon, who argued that Mnetha represents "neoclassical criticism, which protects decadent poetry (Har) and painting (Heva)."[51] Additionally, Har sings in a "great cage" (3:21), which to Damon suggests the heroic couplet, which Blake abhorred.[17] Hilton believes the phrase "great cage" recalls the poem 'Song: "How sweet I roamd from field to field"' from Poetical Sketches (1783), which also deals with oppression and failure to achieve fulfillment.[50] Similarly, in this same line of interpretation, Ostriker argues that "our singing birds" (3:20) and "fleeces" (3:21) suggest neoclassical lyric poetry and pastoral poetry, while Erdman argues that "To catch birds & gather them ripe cherries" (3:13) "signifies triviality and sacchurnity of subject matter", whilst "sing in the great cage" (3:21) "signifies rigidity of form."[52]

Adaptations

Tiriel (Russian: Тириэль) is a 1985 opera with libretto and music by Russian/British composer Dmitri Smirnov partially based on Blake's text. The opera incorporates material from several of Blake's other poems; the "Introduction", "A Cradle Song" and "The Divine Image" from Songs of Innocence (1789), and "The Tyger" from Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1794).

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g Damon (1988: 405)

- ^ a b Bentley (1967)

- ^ All quotations from the poem are taken from Erdman, The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake (1988), which retains both Blake's inconsistent spelling and often bizarre punctuation.

- ^ Erdman (1988: 277)

- ^ Erdman (1988: 281)

- ^ Erdman (1988: 282)

- ^ Erdman (1988: 285)

- ^ a b Ostriker (1977: 879)

- ^ Harold Bloom, "Commentary" in Erdman (1982: 946)

- ^ Erdman (1977: 133-134)

- ^ Erdman (1977: 135)

- ^ Erdman (1977: 137)

- ^ a b c d e Bloom (1982: 946)

- ^ a b c d e f Frye (1947: 242)

- ^ a b Frye (1947: 243)

- ^ Erdman (1977: 133n41)

- ^ a b c d e Damon (1988: 174)

- ^ Mellor (1974: 30)

- ^ a b c Ostriker (1977: 880)

- ^ a b c d e Damon (1988: 406)

- ^ Stevenson (2007: 88)

- ^ a b Bogen (1969: 150)

- ^ Damon (1988: 457)

- ^ Ostriker (1977: 879-880)

- ^ Hall (1969: 170)

- ^ Hall (1969: 174)

- ^ Frye (1947: 243-244)

- ^ Mellor (1974: 31)

- ^ Erdman (1982: 814)

- ^ All information regarding deleted material taken from Erdman (1982: 814-815)

- ^ Erdman (1988: 814-815)

- ^ Erdman (1988: 815)

- ^ a b c Ackroyd (1995: 110)

- ^ Damon (1988: 16)

- ^ Bindman (2003: 90)

- ^ Erdman (1988: 83)

- ^ Erdman (1988: 68)

- ^ Damon (1988: 407)

- ^ Frye (1947: 245)

- ^ Damon (1988: 179)

- ^ Raine (1968: 34)

- ^ Stevenson (2007: 80)

- ^ Frye (1947: 244)

- ^ Erdman (1977: 131-132)

- ^ Erdman (1977: 151)

- ^ Erdman (1977: 140)

- ^ Mellor (1974: 28)

- ^ Mellor (1974: 29-30)

- ^ Mellor (1974: 33)

- ^ a b Hilton (2003: 195)

- ^ Damon (1988: 282)

- ^ Erdman (1977: 134n43)

Further reading

- Ackroyd, Peter. Blake (London: Vintage, 1995)

- Behrendt, Stephen C. "The Worst Disease: Blake's Tiriel", Colby Library Quarterly, 15:3 (Fall, 1979), 175-87

- Bentley, G.E. and Nurmi, Martin K. A Blake Bibliography: Annotated Lists of Works, Studies and Blakeana (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1964)

- Bentley, G.E. (ed.) Tiriel: facsimile and transcript of the manuscript, reproduction of the drawings and a commentary on the poem (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967)

- ——— . (ed.) William Blake: The Critical Heritage (London: Routledge, 1975)

- ——— . Blake Books: Annotated Catalogues of William Blake's Writings (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977)

- ——— . William Blake's Writings (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978)

- ——— . The Stranger from Paradise: A Biography of William Blake (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001)

- Bindman, David. "Blake as a Painter" in Morris Eaves (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to William Blake (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 85-109

- Bogen, Nancy. "A New Look at Blake's Tiriel", BYNPL, 73 (1969), 153-165

- Damon, S. Foster. A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake (Hanover: University Press of New England 1965; revised ed. 1988)

- Erdman, David V. Blake: Prophet Against Empire (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1954; 2nd ed. 1969; 3rd ed. 1977)

- ——— . (ed.) The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake (New York: Anchor Press, 1965; 2nd ed. 1982; Newly revised ed. 1988)

- Essick, Robert N. "The Altering Eye: Blake's Vision in the Tiriel Designs" in Morton D. Paley and Michael Phillips (eds.), Essays in Honour of Sir Geoffrey Keynes (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973), 50-65

- Frye, Northrop. Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1947)

- Gilchrist, Alexander. Life of William Blake, "Pictor ignotus". With selections from his poems and other writings (London: Macmillan, 1863; 2nd ed. 1880; rpt. New York: Dover Publications, 1998)

- Hall, Mary S. "Tiriel: Blake's Visionary Form Pedantic", BYNPL, 73 (1969), 166-176

- Raine, Kathleen. "Some Sources of Tiriel", Huntington Library Quarterly, 21:1 (November, 1957), 1-36

- ——— . Blake and Tradition (New York: Routledge, 1968)

- Hilton, Nelson. "Literal/Tiriel/Material", in Dan Miller, Mark Bracher and Donald Ault (eds.), Critical Paths: Blake and the Argument of Method (Durham: Duke University Press, 1987), 99-110

- ——— . "Blake's Early Works" in Morris Eaves (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to William Blake (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 191-209

- Keynes, Geoffrey. (ed.) The Complete Writings of William Blake, with Variant Readings (London: Nonesuch Press, 1957; 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1966)

- Mellor, Anne Kostelanetz. Blake's Human Form Divine (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1974)

- Ostriker, Alicia (ed.) William Blake: The Complete Poems (London: Penguin, 1977)

- Ostrom, Hans. "Blake's Tiriel and the Dramatization of Collapsed Language," Papers On Language and Literature, 19:2 (Spring, 1983), 167-182

- Sampson, John (ed.) The poetical works of William Blake; a new and verbatim text from the manuscript engraved and letterpress originals (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1905)

- Schuchard, Marsha Keith. "Blake's Tiriel and the Regency Crisis: Lifting the Veil on a Royal Masonic Scandal", in Jackie DiSalvo, G.A. Rosso and Christopher Z. Hobson (eds.), Blake, Politics, and History (New York: Garland, 1998) 115-35

- Spector, Sheila A. "Tiriel as Spenserian Allegory Manqué", Philological Quarterly, 71:3 (Autumn, 1992), 313-35

- Stevenson, W.H. (ed.) Blake: The Complete Poems (Longman Group: Essex, 1971; 2nd ed. Longman: Essex, 1989; 3rd ed. Pearson Education: Essex, 2007)