Tigalari script

| Tigalari | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | 9th century CE – present[1] |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Tutg (341), Tulu-Tigalari |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Tulu Tigalari |

| U+11380–U+113FF | |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmi script and its descendants |

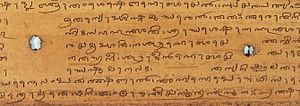

Tigalari (Tulu: Tigaḷāri lipi, , IPA: [t̪iɡɐɭaːri lipi]) or Tulu script (Tulu: tulu lipi)[a] is a Southern Brahmic script which was used to write Tulu, Kannada, and Sanskrit languages. It was primarily used for writing Vedic texts in Sanskrit.[3] It evolved from the Grantha script.

The oldest record of the usage of this script found in a stone inscription at the Sri Veeranarayana temple in Kulashekara here is in complete Tigalari/Tulu script and Tulu language and belongs to the 1159 CE.[4] The various inscriptions of Tulu from the 15th century are in the Tigalari script. Two Tulu epics named Sri Bhagavato and Kaveri from the 17th century were also written in the same script.[5] It was also used by Tulu-speaking Brahmins like Shivalli Brahmins and Kannada speaking Havyaka Brahmins and Kota Brahmins to write Vedic mantras and other Sanskrit religious texts. However, there has been a renewed interest among Tulu speakers to revive the script as it was formerly used in the Tulu-speaking region. The Karnataka Tulu Sahitya Academy, a cultural wing of the Government of Karnataka, has introduced Tuḷu language (written in Kannada script) and Tigalari script in schools across the Mangalore and Udupi districts.[6] The academy provides instructional manuals to learn this script and conducts workshops to teach it.[7]

Names

| Name of the script | Prevalent in | References to their roots |

|---|---|---|

| Arya Ezhuttu Grantha Malayalam |

Kerala, Parts of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu | Malayalam Speakers, Manipravala, Tamil Grantha |

| Western Grantha Tulu-Malayalam |

Few academic publications | 19th Century Western Scholars |

| Tulu-Tigalari | Malenadu and Karavali regions of Karnataka | Kannada speakers, Havyaka Brahmins, National Manuscript Mission Catalogues |

| Tulu Lipi Tulu Grantha Lipi |

Coastal Karnataka, Tulu Nadu | Tulu speakers, A C Burnell |

The name by which this script is referred to is closely tied with its regional, linguistic or historical roots. It would not be wrong to assign all the names mentioned above to this script.[6]

Arya Ezhuttu, or the more recently coined term Grantha Malayalam, is used to refer to this script in Kerala. Arya Ezhuttu covers the spectrum between the older script (that is Tigalari) until it was standardised by the lead types for Malayalam script (old style) in Kerala.[6]

Tigalari is used to this day by the Havyaka Brahmins of the Malanadu region. Tigalari is also the term that is commonly used to refer to this script in most manuscript catalogues and in several academic publications today. Gunda Jois has studied this script closely for over four decades now. According to his findings that were based on evidences found in stone inscriptions, palm leaf manuscripts and early research work done by western scholars like B. L. Rice, he finds the only name used for this script historically has been Tigalari.[6]

It is referred to as Tigalari lipi in Kannada-speaking regions (Malnad region) and Tulu speakers call it as Tulu lipi. It bears high similarity and relationship to its sister script Malayalam, which also evolved from the Grantha script.

This script is commonly known as the Tulu script or Tulu Grantha script in the coastal regions of Karnataka. There are several recent publications and instructional books for learning this script. It is also called the Tigalari script in—Elements of South Indian Palaeography by Rev. A C Burnell and a couple of other early publications of the Basel Mission press, Mangalore. Tulu Ramayana manuscript found in the Dharmasthala archives refers to this script as Tigalari Lipi.

Geographical distribution

The script is used all over Canara and Western Hilly regions of Karnataka. Many manuscripts are also found North Canara, Udupi, South Canara, Shimoga, Chikkamagaluru and Kasaragod district of Kerala. There are innumerable manuscripts found in this region. The major language of manuscripts is Sanskrit, mainly the works of Veda, Jyotisha and other Sanskrit epics.

Usage

Historical use

Thousands of manuscripts have been found in this script such as Vedas, Upanishads, Jyotisha, Dharmashastra, Purana and many more. Most works are in Sanskrit. However, some Kannada manuscripts are also found such as Gokarna Mahatmyam etc. The popular 16th-century work Kaushika Ramayana written in Old Kannada language by Battaleshwara of Yana, Uttara Kannada is found in this script. Mahabharato of 15th century written in this script in Tulu language is also found. But earlier to this several 12th-13th century Sanskrit manuscripts of Madhvacharya are also found. Honnavar in Uttara Kannada District is known for its Samaveda manuscripts. Other manuscripts like Devi Mahatmyam, from the 15th century and two epic poems written in the 17th century, namely Sri Bhagavato and Kaveri have also been found in Tulu language.

Modern use

Today the usage of the script has decreased. It is still used in parts of Kanara region and traditional maṭhas of undivided Dakshina Kannada and Uttara Kannada Districts.

The National Mission for Manuscripts has conducted several workshops on Tigalari script. Dharmasthala and the Ashta Mathas of Udupi have done significant work in preserving the script. Several studies and research work has been done on Tigalari script. Keladi houses over 400 manuscripts in Tigalari script.

There is a gaining support and interest by Tuluvas in revival of the script. Karnataka Tulu Sahitya Academy is constantly conducting meetings with experts for standardisation of Tulu script.[8] There is also huge support from Local MLAs for popularising the Tulu script.[9]

There are many places in Tulu Nadu region where sign boards are being installed in Tulu script.[10][11]

Preservation

- Keladi Museum & Historical Research Bureau, Shimoga, Karnataka

- The museum has a library of about a thousand paper and palm leaf manuscripts written in Kannada, Sanskrit, Tamil and Telugu, besides four hundred palm leaf manuscripts in Tigalari script. They relate to literature, art, dharmaśāstra, history, astrology, astronomy, medicine, mathematics and veterinary science. There are several collections in the museum, including art objects, arms coins, stone sculptures and copper plate inscriptions belonging to the Vijayanagara and Keladi eras. The Institution is affiliated to Gnana Sahyadri, Shankaraghatta, Kuvempu University of Shimoga.

- Oriental Research Institute Mysore

- The Oriental Research Institute Mysore houses over 33,000 palm leaf manuscripts. It is a research institute which collects, exhibits, edits and publishes rare manuscripts in both Sanskrit and Kannada. It contains many manuscripts, including Sharadatilaka, in Tigalari script. The Sharadatilaka is a treatise on theory and practice of Tantric worship. While the exact date of the composition is not known, the manuscript itself is thought to be about four hundred years old. The author of the text, Lakshmana Deshikendra, is said to have written the text as an aid to worship for those unable to go through voluminous Tantra texts. The composition contains the gist of major Tantra classics and is in verse form.

- Saraswathi Mahal Library, Thanjavur

- Built up by the Nayak and Maratha dynasties of Thanjavur, Saraswathi Mahal Library contains a very rare and valuable collection of manuscripts, books, maps and painting on all aspects of arts, culture and literature. The scripts include Grantha, Devanagari, Telugu and Malayalam, Kannada, Tamil, Tigalari and Oriya.

- French Institute of Pondicherry

- The French Institute of Pondicherry was established in 1955 with a view to collecting all material relating to Saiva Āgamas, scriptures of the Saiva religious tradition called the Shaiva Siddhanta, which has flourished in South India since the eighth century BCE The manuscript collection of the Institute[12] was compiled under its Founder–Director, Jean Filliozat. The manuscripts, which are in need of urgent preservation, cover a wide variety of topics such as Vedic ritual, Saiva Agama, Sthalapurana and scripts, such as Grantha and Tamil. The collection consists of approximately 8,600 palm-leaf codices, most of which are in the Sanskrit language and written in Grantha script; others are in Tamil, Malayalam, Telugu, Nandinagari and Tigalari scripts.

- The Shaiva Agama is composed in Sanskrit and written in Tigalari script. Though there may be a few copies of these texts available elsewhere, this particular codex comes from southern Karnataka, providing glimpses into the regional variations and peculiarities in ritual patterns. The manuscript was copied in the 18th century on (sritala) palm leaf manuscripts.

Apart from these they are also found in Dharmasthala, Ramachandrapura Matha of Hosanagar, Shimoga, Sonda Swarnavalli Matha of Sirsi and the Ashta Mathas of Udupi.

Characters

A chart showing a complete list of consonant and vowel combinations used in the Tigalari script.

Comparison with other scripts

Tigalari and Malayalam are both descended from Grantha script, and resemble each other both in their individual letters and in using consonant conjuncts less than other Indic scripts. It is assumed that a single script around 9th-10th century called Western Grantha, evolved from Grantha script and later divided into two scripts.[13]

The following table compares the consonants ka, kha, ga, gha, ṅa with other Southern Indic scripts such as Grantha, Tigalari, Malayalam, Kannada and Sinhala.

Unicode

The Tigalari script was added to the Unicode Standard in September 2024 with the release of version 16.0. The Unicode block for Tigalari, named Tulu-Tigalari, is located at U+11380–U+113FF:

| Tulu-Tigalari[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1138x | | | | | | | | | | | | | ||||

| U+1139x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+113Ax | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+113Bx | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+113Cx | | | | | | | | | | | | |||||

| U+113Dx | | | | | | | | | ||||||||

| U+113Ex | | | ||||||||||||||

| U+113Fx | ||||||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Notes

References

- ^ Diringer, David (1948). Alphabet a key to the history of mankind. p. 385.

- ^ Handbook of Literacy in Akshara Orthography, R. Malatesha Joshi, Catherine McBride(2019), p.28

- ^ "ScriptSource - Tigalari". scriptsource.org.

- ^ "Tulu stone inscription in Veeranarayana temple belongs to 1159 A.D.: Historian". The Hindu. 22 February 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ Steever, Sanford B (2015). The Dravidian Languages. Routledge. pp. 158–163. ISBN 9781136911644.

- ^ a b c d Vaishnavi Murthy K Y; Vinodh Rajan. "L2/17-378 Preliminary proposal to encode Tigalari script in Unicode" (PDF). unicode.org. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ Kamila, Raviprasad (23 August 2013). "Tulu academy's script classes attract natives". The Hindu. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ Shenoy, Jaideep (30 November 2019). "Karnataka Tulu Sahitya academy to convene meet of experts for standardisation of Tulu script". The Times of India. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ Shenoy, Jaideep (18 November 2019). "MLA Vedavyas Kamath gives Tulu an online fillip". The Times of India. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ Monteiro, Walter (21 July 2020). "Karkala: Nandalike Abbanadka Friends Club inaugurates road signboard in Tulu". Daijiworld. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ DHNS, Harsha (21 June 2020). "Athikaribettu GP's initiative to publicise Tulu gets good response". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ The digitized Tigalari manuscripts can be viewed at "Welcome to the IFP Manuscripts Database". Archived from the original on 24 November 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ Andronov, Mikhail Sergeevich. A Grammar of the Malayalam Language in Historical Treatment. Wiesbaden : Harrassowitz, 1996.

Further reading

- S. Muhammad Hussain Nainar (1942), Tuhfat-al-Mujahidin: An Historical Work in The Arabic Language, University of Madras, ISBN 9789839154801

- J. Sturrock (1894), Madras District Manuals - South Canara (Volume-I), Madras Government Press

- Harold A. Stuart (1895), Madras District Manuals - South Canara (Volume-II), Madras Government Press

- Government of Madras (1905), Madras District Gazetteers: Statistical Appendix for South Canara District, Madras Government Press

- Government of Madras (1915), Madras District Gazetteers South Canara (Volume-II), Madras Government Press

- Government of Madras (1953), 1951 Census Handbook- South Canara District (PDF), Madras Government Press

- J. I. Arputhanathan (1955), South Kanara, The Nilgiris, Malabar and Coimbatore Districts (Village-wise Mother-tongue Data for Bilingual or Multilingual Taluks) (PDF), Madras Government Press

- Rajabhushanam, D. S. (1963), Statistical Atlas of the Madras State (1951) (PDF), Madras (Chennai): Director of Statistics, Government of Madras

See also

External links

- Tulu Alphabet - Tulu Lipi: Tulu Akshara Male by GVS Ullal

- Lessons on Tulu alphabets by Karnataka Tulu Sahitya Academy

- Tending to the Inheritance of Tulu Script