Theria

| Theria Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Clade: | Tribosphenida |

| Subclass: | Theria Parker & Haswell, 1897[1] |

| Subgroups | |

| |

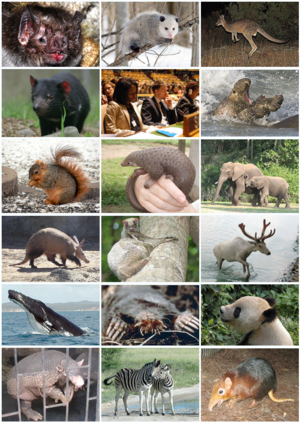

Theria (/ˈθɪəriə/ or /ˈθɛriə/; from Ancient Greek θηρίον (thēríon) 'wild beast') is a subclass of mammals[2] amongst the Theriiformes. Theria includes the eutherians (including the placentals) and the metatherians (including the marsupials) but excludes the egg-laying monotremes and various extinct mammals evolving prior to the common ancestor of placentals and marsupials.

Characteristics

Therians give birth to live young without a shelled egg. This is possible thanks to key proteins called syncytins which allow exchanges between the mother and its offspring through a placenta, even rudimental ones such as in marsupials. Genetic studies have suggested a viral origin of syncytins through the endogenization process.[3]

The marsupials and the placentals evolved from a common therian ancestor that gave live birth by suppressing the mother's immune system. While the marsupials continued to give birth to an underdeveloped fetus after a short pregnancy, the ancestors of placentals gradually evolved a prolonged pregnancy.[4]

An approximately 21-28 day estrous cycle/menstrual cycle occurs in therian females.[5]

The exit openings of the urogenital system and the rectal opening (anus) are separated.

The mammary glands lead to the teats.

Therians no longer have the coracoid bone, unlike their cousins, monotremes.

Pinnae (external ears) are also a distinctive trait that is a therian exclusivity, though some therians, such as the earless seals, have lost them secondarily.[6]

The flexible and protruding nose in therians is not found in any other vertebrates, and is the product of modified cells involved in the development of the upper jaw in other tetrapods.[7]

Almost all therians have whiskers.[8]

The SRY gene is a protein in therians that helps initiate male sex determination.[9]

Evolution

The earliest known therian mammal fossil is Juramaia, from China's Late Jurassic (Oxfordian stage). However, the age estimates of the site are disputed based on the geological complexity and the geographically widespread nature of the Tiaojishan Formations.[10][11] Further, King and Beck in 2020 argue for an Early Cretaceous age for Juramaia sinensis, in line with similar early mammaliaformes.[12]

A recent review of the Southern Hemisphere Mesozoic mammal fossil record has argued that triosphenic mammals arose in the Southern Hemisphere during the Early Jurassic, around 50 million years prior to the clade's earliest undisputed appearance in the Northern Hemisphere.[13]

Molecular data suggests that therians may have originated even earlier, during the Early Jurassic.[14] Therian mammals began to diversify 10-20 million years before the dinosaur extinction.[15]

Taxonomy

The rank of "Theria" may vary depending on the classification system used. The textbook classification system by Vaughan et al. (2000)[16] gives the following:

|

Class Mammalia

|

In the above system, Theria is a subclass. Alternatively, in the system proposed by McKenna and Bell (1997)[17] it is ranked as a supercohort under the subclass Theriiformes:

|

Class Mammalia

|

Another classification proposed by Luo et al. (2002)[18] does not assign any rank to the taxonomic levels, but uses a purely cladistic system instead.

See also

References

- ^ ITIS Standard Report Page: Theria

- ^ Myers, P.; R. Espinosa; C. S. Parr; T. Jones; G. S. Hammond & T. A. Dewey. "Subclass Theria". Animal Diversity Web.

- ^ Cornelis, G.; Vernochet, C.; Carradec, Q.; Souquere, S.; Mulot, B.; Catzeflis, F.; Nilsson, M. A.; Menzies, B. R.; Renfree, M. B.; Pierron, G.; Zeller, U.; Heidmann, O.; Dupressoir, A.; Heidmann, T. (2015). "Retroviral envelope gene captures and syncytin exaptation for placentation in marsupials". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (5): E487 – E496. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112E.487C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1417000112. PMC 4321253. PMID 25605903.

- ^ "Ancient "genomic parasites" spurred evolution of pregnancy in mammals". UChicago Medicine. January 29, 2015. Archived from the original on Jan 14, 2024.

- ^ Hill, M. A. (2021, April 6) Embryology Estrous Cycle. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Estrous_Cycle

- ^ SUMIYAMA K; MIYAKE T; GRIMWOOD J; STUART A; DICKSON M; SCHMUTZ J; RUDDLE FH; MYERS RM; AMEMIYA CT (2012). "Theria-Specific Homeodomain and cis-Regulatory Element Evolution of the Dlx3–4 Bigene Cluster in 12 Different Mammalian Species". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 318 (8): 639–650. Bibcode:2012JEZB..318..639S. doi:10.1002/jez.b.22469. PMC 3651898. PMID 22951979.

- ^ Higashiyama, H.; Koyabu, D.; Hirasawa, T.; Werneburg, I.; Kuratani, S.; Kurihara, H. (2021). "Mammalian face as an evolutionary novelty". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (44): e2111876118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11811876H. doi:10.1073/pnas.2111876118. PMC 8673075. PMID 34716275.

- ^ Andrew M. Baker (2023). Strahan's Mammals of Australia. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-39941-420-3. Retrieved 10 December 2024.

- ^ Berta P, Hawkins JR, Sinclair AH, Taylor A, Griffiths BL, Goodfellow PN, Fellous M (November 1990). "Genetic evidence equating SRY and the testis-determining factor". Nature. 348 (6300): 448–50. Bibcode:1990Natur.348..448B. doi:10.1038/348448A0. PMID 2247149. S2CID 3336314.

- ^ Bi, Shundong; Zheng, Xiaoting; Wang, Xiaoli; Cignetti, Natalie E.; Yang, Shiling; Wible, John R. (June 2018). "An Early Cretaceous eutherian and the placental-marsupial dichotomy". Nature. 558 (7710): 390–395. Bibcode:2018Natur.558..390B. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0210-3. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 29899454. S2CID 49183466.

- ^ Meng, Jin (2014). "Mesozoic mammals of China: implications for phylogeny and early evolution of mammals". National Science Review. 1 (4): 521–542. doi:10.1093/nsr/nwu070.

- ^ King, Benedict; Beck, Robin M. D. (2020-06-10). "Tip dating supports novel resolutions of controversial relationships among early mammals". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 287 (1928): 20200943. doi:10.1098/rspb.2020.0943. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 7341916. PMID 32517606.

- ^ Flannery, Timothy F.; Rich, Thomas H.; Vickers-Rich, Patricia; Veatch, E. Grace; Helgen, Kristofer M. (2022-10-02). "The Gondwanan Origin of Tribosphenida (Mammalia)". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 46 (3–4): 277–290. Bibcode:2022Alch...46..277F. doi:10.1080/03115518.2022.2132288. ISSN 0311-5518.

- ^ Hugall, A.F. et al. (2007) Calibration choice, rate smoothing, and the pattern of tetrapod diversification according to the long nuclear gene RAG-1. Syst Biol. 56(4):543-63.

- ^ Golembiewski, Kate (2 June 2016). "Mammals began their takeover long before the death of the dinosaurs". Field Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ^ Vaughan, Terry A., James M. Ryan, and Nicholas J. Czaplewski. 2000. Mammalogy: Fourth Edition. Saunders College Publishing, 565 pp. ISBN 0-03-025034-X

- ^ McKenna, Malcolm C., and Bell, Susan K. 1997. Classification of Mammals Above the Species Level. Columbia University Press, New York, 631 pp. ISBN 0-231-11013-8

- ^ Luo, Z.-X., Z. Kielan-Jaworowska, and R. L. Cifelli. 2002. In quest for a phylogeny of Mesozoic mammals. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 47:1-78.