Victoria Rooms, Bristol

| Victoria Rooms | |

|---|---|

The Victoria Rooms now house the University of Bristol's Department of Music. | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Greek revival |

| Town or city | Bristol |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 51°27′29″N 2°36′33″W / 51.458°N 2.6091°W |

| Construction started | 1838 |

| Completed | 1842 |

| Cost | £23,000 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Charles Dyer |

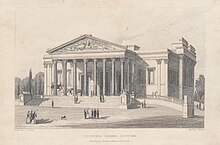

The Victoria Rooms, also known as the Vic Rooms, houses the University of Bristol's music department in Clifton, Bristol, England, on a prominent site at the junction of Queens Road and Whiteladies Road. The building, originally assembly rooms, was designed by Charles Dyer and was constructed between 1838 and 1842 in Greek revival style, and named in honour of Queen Victoria, who had acceded to the throne in the previous year. An eight column Corinthian portico surmounts the entrance, with a classical relief sculpture designed by Musgrave Watson above. The construction is of dressed stonework, with a slate roof. A bronze statue of Edward VII, was erected in 1912 at the front of the Victoria Rooms, together with a curved pool and several fountains with sculptures in the Art Nouveau style.

The Victoria Rooms contain a 665-seat auditorium, a lecture theatre, recital rooms, rehearsal rooms and a recording studio. Jenny Lind and Charles Dickens performed at the Victoria Rooms. It was also the venue for important dinners and assemblies, including banquets to commemorate the opening of the Clifton Suspension Bridge and the quatercentennial anniversary of Cabot's discovery of North America, meetings which led to the establishment of the University College, Bristol, an early congress of the British Association for the Advancement of Science and suffragettes "at-homes". The building was purchased and given to the university in 1920 as a home for the student union and, circa 1924, it spent a brief period as a cinema. Following a fire in 1934, the building was refurbished by the university. It remained as the base of the student union until purpose-built facilities were opened in Queens Road in the 1960s. The Victoria Rooms then became an exhibition and conference centre, before housing the music department in 1996. They remain in use in the 21st century for concerts, exhibitions, plays, recitals and lectures.

The building

The Victoria Rooms, also known colloquially as the Vic Rooms,[1] are situated at the junction of Queen's Road and Whiteladies Road, in Clifton, Bristol, "occupying one of the finest sites in Clifton," according to a 1906 visitor's guide.[2] Gomme, in Bristol: an architectural history (1979), described it as a key building on a prominent intersection.[3] The building was designed as assembly rooms by Charles Dyer. The foundation stone was laid on 24 May 1838, the 19th birthday of Queen Victoria, in whose honour the building was named.[4][5]

Building works in the Greek revival style, incorporating an eight-columned Corinthian portico which is 30 feet (9.1 m) tall, were completed in 1842.[6][7] It is constructed of ashlar (dressed stone work) with steps leading up to the portico. The roof is of slate.[8] Two sloping ramps were built to allow the passage of carriages into the building.[9] The pediment in the blind attic above the columns has a relief carving attributed to Musgrave Watson "depicting Wisdom in her chariot ushering in the morning, and followed by the Three Graces", according to Andrew Foyle in Pevsner's Guide. He adds that the main hall was disappointingly remodelled in 1935, following a fire the previous year.[10] In 1838, the design of the interior was described as "nothing either particularly remarkable or new in regard to design" in the Civil Engineer and Architects' Journal.[11] In 1849, the interior of the hall was described by Chilcott, in his Descriptive history of Bristol as being decorated in a Greek theme, to match the exterior of the building.[12] Gomme describes the pediment sculpture as "Minerva in car driven by Apollo, accompanied by the Hours and Graces", attributing the sculpture to Jabez Tyley.[3] Henry Lonsdale, writing in 1866, explains this anomaly by revealing that Tyley created the sculpture in Bath Stone from a plaster of paris model by Watson.[13] The architecture of the building is described by English Heritage as "a product of European trends of the time, moving away from Neoclassicism and towards Roman Corinthian design."[8] It has been designated by English Heritage as a Grade II* listed building.[14]

Inside the main entrance is a vestibule which then leads via an octagonal room, with a bowed cast-iron railed balcony and a domed ceiling, to the main auditorium. A correspondent of the Bristol Mercury, in 1846, described an ingenious central heating system consisting of a cast iron stove which heated and circulated air, "using less than half a cwt. [25 kilograms (55 lb)] of Welsh anthracite in twenty-four hours", kept the interior of the building some 30 to 40 °F (16 to 22 °C) higher than the external temperature.[15] Much of the interior was remodeled in the mid-20th century, although some period plaster decorations remain in the Regency room.[14] From 1873 the main auditorium housed a large organ originally built for the Royal Panopticon of Arts and Science in Leicester Square, from where it was removed to St Paul's Cathedral and thence to the Victoria Rooms. In July 1899 it was decided to replace this with an electric organ, which could be played from a keyboard at a considerable distance from the organ itself. The organ was built by Norman & Beard, and was first played by Edwin Lemare on 31 October 1900;[16] On 1 December 1934, a fire started under the stage of the great hall or auditorium, quickly spreading. The Times reported that "The brigades were able to no more than prevent the fire from extending to the Lesser Hall and the recreation rooms. The fine electric organ was completely destroyed."[17][18]

In the 21st century, the building houses a 665-seat auditorium and rehearsal rooms. The auditorium is approximately 418 square metres (4,500 sq ft), with an adjacent lecture theatre of some 119 square metres (1,280 sq ft) and a recital room of 139 square metres (1,500 sq ft). The purpose-built composition and recording studios are in regular use for research and the creation of works.[19] Other facilities include a bar, common rooms, a resource centre and practice rooms.[20]

Forecourt

The building was originally surrounded by iron railings as shown in 19th century photographs, but these are no longer there, possibly removed during the Second World War as part of a nationwide scrap drive.[21]

A memorial statue of Edward VII, designed by Edwin Alfred Rickards and executed by Henry Poole RA, was erected in 1912 at the front of the Victoria Rooms, together with a curved pool, lamps, steps, balustrades, ornamental crouching lions and fountains with sculptures in the Art Nouveau style.[8][22] Two sphinxes, which had previously guarded the building, were removed for these new works.[23] The statue and fountains are regarded as fine examples of Rickards and Poole's work and have been Grade II* listed.[24] An interesting feature of the fountains is that the water flow is controlled by an anemometer "so that on windy days the pressure is reduced in order that the water does not blow across the adjacent roadway."[25]

History

At the laying of the foundation stone on 24 May 1838 the President of the Victoria Rooms, Thomas Daniel, opened the ceremony by saying 'I congratulate you, my friends, that this, the birth-day of our amiable and virtuous Queen, has been selected to lay the foundation-stone of these rooms, which are intended for Conservative purposes – rooms where all may meet to assert their loyalty and attachment to the throne, and to support their religion, and the best interests of their country.' P. F. Aiken Esq went on to make a speech including the following: '... The stately edifice we are going to erect, our children's children will look upon with admiring eyes, and generations yet unborn will throng its spacious halls... public buildings are memorials of the age, the city, the country in which they are erected, and indicate their progress in civilization to future generations.'[26]

The Victoria Rooms were opened on 24 May 1842; building had begun in 1838, and cost about £23,000.'.The money was raised by a "body of Conservative citizens".[6]

Jenny Lind[27] and Charles Dickens[6] were just two of the artists known to have performed there. Numerous private subscription balls were held at the rooms, in competition with those organised at the assembly rooms in the Mall, Clifton. This rivalry occasioned disputes between the promoters and accusations of prejudice and snobbery.[28] Other uses included what was the first public demonstration of electric lighting in Bristol in 1863.[29] It was also the scene for large banquets, such as that to celebrate the opening of the Clifton Suspension Bridge in 1864,[1] and the celebrations, in 1897, of the four hundredth anniversary of John Cabot's 'discovery' of North America.[30]

On 11 June 1874 the Victoria Rooms hosted a meeting to promote what was described as a College of Science and Literature for the West of England and South Wales, which became University College, Bristol, an educational institution which existed from 1876 to 1909.[31] It was the predecessor institution to the University of Bristol, which gained a royal charter in 1909.[32] The meeting was attended by the then President of the British Association and Sir William Thompson (later Lord Kelvin). This meeting has been described as a partial success, as it gained the support of Albert Fry and Lewis Fry,[33] members of the influential Fry family (the Fry name being known for the chocolate business set up by their grandfather and developed by their father Joseph Storrs Fry). Lewis Fry was a Quaker, lawyer and later a Liberal and Unionist Member of Parliament from 1885 to 1892 and from 1895 to 1890 for the constituency Bristol North.[34] In 1898 the third congress of the British Association for the Advancement of Science was held at the rooms.[35]

In the early twentieth century, Annie Kenney and Clara Codd, local organisers of the Women's Social and Political Union (the suffragettes), used the Victoria Rooms to host "at homes", to which all were invited.[36] In 1920, the rooms were purchased from the original private company by wealthy local industrialist Sir George Wills and given to the university to house the students' union.[37] It appears that the university briefly leased the building for use as the Clifton Cinema which was situated there in March 1924, when local photographer Reece Winstone took a photograph. All seats were priced at 1/3d.[38] The Victoria Rooms remained the base for the student union until 1964 when a purpose-built facility was constructed in nearby Queen's Road. The building then became a conference and exhibition centre, hosting occasional concerts such as those by Pink Floyd in 1967 and 1969.[39] In 1987 the building housed the first incarnation of the Exploratory founded by Richard Gregory – a hands-on science centre and precursor of At-Bristol – until 1989.[40][41] The University Music Department was moved into the Victoria Rooms in 1996.[8]

The venue, in the 21st century, has a regular programme of concerts, theatrical performances, lectures and conferences,[42] serving a similar purpose to that for which the building was constructed in the nineteenth century.[43]

References

- ^ a b "The Victoria Rooms". Bristol University. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ Arrowsmith, John (1906). How to see Bristol. J W Arrowsmith. pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b Gomme, Andor Harvey; Jenner, Michael; Little, Bryan (1979). Bristol: an architectural history. Lund Humphries. p. 245. ISBN 0853314098.

- ^ Latimer (1887), p.241

- ^ Basil Cottle (1951). The life of a university. Published for the University of Bristol by J. W. Arrowsmith. p. 94. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- ^ a b c Latimer (1887), p.329

- ^ The Penny Magazine. 1838. p. 504. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Detailed Result: Victoria Rooms". Pastscape. English Heritage. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ L. (September 1846). "Architectural Study and Records". The Westminster Review. XLV: 50.

- ^ Foyle, p.228

- ^ Civil engineer and architects' journal, incorporated with the Architect. William Laxton. 1838. p. 224. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- ^ John Chilcott (1849). Chilcott's descriptive history of Bristol. p. 269. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- ^ Lonsdale, Henry (1866). The Life and Works of Musgrave Lewthwaite Watson. George Routledge and Sons. pp. 130–132.

- ^ a b National Monuments Record. "Victoria Rooms and attached railings and gates". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 23 March 2007.

- ^ Jeffery, MD, J (6 June 1846). "Warming and Ventilation". Bristol Mercury.

- ^ Arrowsmith's Dictionary of Bristol, 1906.

- ^ James Boeringer; Andrew Freeman (1989). Organa britannica: Organs in Great Britain 1660–1860 : a complete edition of the Sperling notebooks and drawings in the library of the Royal College of Organists. Associated University Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-8387-5044-5. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- ^ Staff (3 December 1934). "Outbreak after a Dance". The Times, archived at Times Digital archive.

- ^ "Composition and Recording Studios". Bristol University. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ "Facilities in the Department of Music". Bristol University. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ Stamp, Gavin (27 August 2010). "Architecture – Bring Back the Railings". Apollo Magazine. Press Holdings. Archived from the original on 4 September 2010. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ Historic England. "Fountains, Lamps, Balustrades, Railings And Statues To Front of Victoria Rooms (1218308)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ Crick, Clare (1975). Victorian buildings in Bristol. Bristol & West Building Society. p. 24.

- ^ National Monuments Record. "Fountains, lamps, balustrades, railings and statues to front of Victoria Rooms". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 23 March 2007.

- ^ "Bristols Fascinating Fountains" (PDF). Temple Local History Group. 27 September 1994. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ^ "Royal Victoria Rooms". Bristol Mercury. 26 May 1838.

- ^ Latimer (1887), p.259

- ^ Latimer (1887), p.320-321

- ^ "Conservation Area 5: Clifton & Hotwells – Character Appraisal & Management Proposals)". Environment and Planning. Bristol City Council. June 2010. p. 68. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ Latimer (1902), p.60

- ^ "NNDB". Bristol University, Educational Institution. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- ^ "Bristol University History". Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- ^ Carleton, Don (1984). University for Bristol: A History in Text and Pictures. Bristol: University of Bristol. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-86292-200-9.

- ^ "Leigh Rayment's Peerage Page". The House of Commons Constituencies beginning with "B". Archived from the original on 10 August 2009. Retrieved 4 June 2008.

- ^ Latimer (1902), p.73

- ^ Crawford, Elizabeth (2006). The women's suffrage movement in Britain and Ireland: a regional survey. Routledge. p. 132. ISBN 0-415-38332-3.

- ^ Official guide to the city of Bristol. J.W. Arrowsmith. 1938. pp. 57–59.

- ^ Winstone, Reece (1971). Bristol in the 1920s. Reece Winstone. ISBN 0-900814-38-1.

Plate 79 – the book has no page numbers

- ^ Povey, Glen (2007). Echoes: the complete history of Pink Floyd. pp. 1952, 1969. ISBN 978-0-9554624-0-5.

- ^ Braddick, Oliver (26 May 2010). "Richard Gregory obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ "History of The Exploratory". The Exploratory. 1 September 1999. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- ^ "Conferences and Hospitality: Victoria Rooms". Bristol University. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ Charles Knight (1854). The English cyclopaedia: a new dictionary of Universal Knowledge. Bradbury and Evans. p. 59. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

Works cited

- Foyle, Andrew (2004). Bristol: Pevsner Architectural Guides. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10442-4.

- Latimer, John (1887). The Annals of Bristol in the Nineteenth Century. Clare Street, Bristol: W A F Morgan.

- Latimer, John (1902). The Annals of Bristol in the Nineteenth Century (concluded). Bristol: William George & Sons.

External links

- Bristol University Music Department

- Victoria Rooms floor plan Archived 6 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine