The Moving Finger

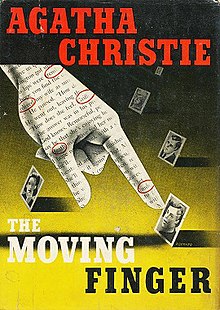

Dust-jacket illustration of the US (true first) edition. See Publication history (below) for UK first edition jacket image. | |

| Author | Agatha Christie |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Series | Miss Marple |

| Genre | Crime novel |

| Publisher | Dodd, Mead and Company |

Publication date | July 1942 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 229 (first edition, hardcover) |

| ISBN | 978-0-00-712084-0 |

| Preceded by | Five Little Pigs (publication) The Body in the Library (series) |

| Followed by | Towards Zero (publication) A Murder Is Announced (series) |

The Moving Finger is a detective novel by British writer Agatha Christie, first published in the USA by Dodd, Mead and Company in July 1942[1] and in the UK by the Collins Crime Club in June 1943.[2] The US edition retailed at $2.00[1] and the UK edition at seven shillings and sixpence.[2]

The Burtons, brother and sister, arrive in the village of Lymstock in Devon, and soon receive an anonymous letter accusing them of being lovers, not siblings. They are not the only ones in the village to receive such letters. A prominent resident is found dead with one such letter found next to her. This novel features the elderly detective Miss Marple in a relatively minor role, "a little old lady sleuth who doesn't seem to do much".[3] She enters the story in the final quarter of the book, in a handful of scenes, after the police have failed to solve the crime.

The novel was well received when it was published: "Agatha Christie is at it again, lifting the lid off delphiniums and weaving the scarlet warp all over the pastel pouffe."[4] One reviewer noted that Miss Marple "sets the stage for the final exposure of the murderer."[3] Another said this was "One of the few times Christie gives short measure, and none the worse for that."[5] The male narrator was both praised and panned.

Title

The book takes its name from quatrain 51 of Edward FitzGerald's translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám:

- The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

- Moves on: not all thy Piety nor Wit

- Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

- Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.

The poem, in turn, refers to Belshazzar's feast as related in the Book of Daniel, where the expression the writing on the wall originated.

The title shows in the story figuratively and literally. The anonymous letters point blame from one town resident to another.[3] The police detective determines that the envelopes were all "typed by someone using one finger" to avoid a recognisable 'touch'.[6]

Plot summary

Jerry and Joanna Burton, a brother and sister from London, take up residence in a house owned by Miss Emily Barton near the quiet town of Lymstock for the last phase of Jerry's recovery from injuries suffered in a crash landing. Shortly after moving in and meeting their neighbours, they receive an anonymous letter which makes the false accusation that the pair are lovers, not siblings.

The Burtons quickly learn that such poison pen letters have been received by many in the town. Despite the letters containing false accusations, many recipients are upset by them and fear something worse may happen. Mrs Symmington, the local solicitor's wife, is found dead after receiving a letter stating that her husband Richard was not the father of her second son. Her body is discovered with the letter, a glass containing potassium cyanide, and a torn scrap of paper that reads, "I can't go on".

While the inquest rules that Mrs. Symmington's death was suicide, the police begin a hunt for the anonymous letter writer. An inspector arrives from Scotland Yard to help with the investigation. He concludes that the letter writer is a middle-aged woman among the prominent citizens of Lymstock. Mrs Symmington's daughter by a previous marriage, Megan Hunter, an awkward, frumpy 20-year-old, stays with the Burtons for a few days after losing her mother.

The Burtons' housekeeper, Partridge, receives a call from Agnes, the Symmingtons' maidservant, who is distraught and seeks advice. Agnes fails to arrive for their planned meeting; nor is she found at the Symmingtons' when Jerry calls in the evening to check on her. The following day, her body is discovered by Megan in the under-stairs cupboard at the Symmington house.

Progress in the murder investigation is slow until the Reverend's wife, Mrs. Dane Calthrop, invites Miss Marple to investigate. Jerry conveys many facts about the case to her from his observations, and tells her some of his ideas on why Agnes was killed. Meanwhile, Elsie Holland, the governess for the Symmington boys, receives an anonymous letter. The police observe Aimée Griffith, sister of the local doctor Owen Griffith, typing the address on the same typewriter used for all the previous letters, and arrest her for writing the letter.

Heading to London to see his doctor, Jerry impulsively takes Megan along with him and takes her to Joanna's dressmaker for a complete makeover. He realises he has fallen in love with Megan. When they return to Lymstock, Jerry asks Megan to marry him; she turns him down. He asks Mr Symmington for his permission to pursue Megan. Miss Marple advises Jerry to leave Megan alone for a day, as she has a task for her.

Megan blackmails her stepfather later that evening, implying that she has proof that he killed Mrs. Symmington. Mr. Symmington coolly pays her an initial instalment of money while not admitting his guilt. Later in the night, after giving Megan a sleeping drug, he attempts to murder her by putting her head in the gas oven. Jerry and the police are lying in wait for him. Jerry rescues Megan, and Symmington confesses. The police arrest him for murdering his wife and Agnes.

Miss Marple, knowing human nature, reveals that she knew all along that the letters were a diversion, and not written by a local woman, because none contained true accusations - something locals would be sure to gossip about. Only one person benefited from Mrs Symmington's death: her husband. He is in love with the beautiful Elsie Holland. Planning his wife's murder, he modelled the letters on those in a past case known to him from his legal practice. The police theory about who wrote them was completely wrong. The one letter that Symmington did not write was the one to Elsie; Aimée Griffith, who had been in love with Symmington for years, wrote that. Knowing it would be hard to prove Symmington's guilt, Miss Marple devised the scheme to expose him, enlisting Megan to provoke him to attempt to kill her.

Following the successful conclusion of the investigation, Megan realises that she does love Jerry. Jerry buys Miss Barton's house for them. His sister Joanna marries Owen Griffith and also stays in Lymstock. Meanwhile, Emily Barton and Aimée Griffith go on a cruise together.

Characters

- Jerry Burton: pilot who was injured in a crash. After a long stint in hospital, he seeks a quiet place for the last stage of healing. Wealthy. He narrates the story.

- Joanna Burton: Jerry's sister, younger and very attractive, who accompanies her brother to Lymstock from their usual home in London.

- Miss Emily Barton: youngest daughter of a large and prim family of sisters, now in her sixties. She owns a house named 'Little Furze', which she rents to the Burtons. Like many in Lymstock, she has received a poison pen letter, but she is unwilling to admit it.

- Florence Elford: the Barton family's former maid, now married, who invites Emily Barton to live with her while she rents 'Little Furze' to the Burtons.

- Partridge: maid at 'Little Furze', who agrees to stay on for the Burtons. She trained Agnes.

- Beatrice Baker: maid at 'Little Furze', who leaves service after she receives an anonymous letter.

- Mrs Baker: mother of Beatrice, who seeks the aid of Jerry when Beatrice's young man receives a letter accusing Beatrice of seeing another man, which is not true.

- Inspector Graves: a detective from Scotland Yard.

- Superintendent Nash: County Detective Superintendent.

- Mr Richard Symmington: solicitor in Lymstock, second husband to Mona, father of two young sons, and stepfather of Megan Hunter.

- Mrs Mona Symmington: mother of Megan Hunter, and of two young sons with Richard Symington. She is the first murder victim, though her murder was made to appear a suicide, fooling the police for a long while.

- Miss Megan Hunter: woman of 20, back home for one year from boarding school, coltish, usually shy, but more comfortable with Jerry and Joanna Burton. She blossoms under their attention. She bravely undertakes a risky ploy at the direction of Miss Marple, exposing the murderer.

- Elsie Holland: beautiful nanny of the two young Symmington sons. Jerry Burton, initially attracted, is turned off by the quality of her voice, but Mr Symmington sees only her beauty.

- Dr Owen Griffith: local doctor in Lymstock, who falls in love with Joanna Burton.

- Aimée Griffith: sister of Owen, who lives with him in Lymstock, is active in the town and for years has been in love with Richard Symmington.

- Miss Jane Marple: a shrewd judge of human nature, resident of the village of St. Mary Mead and a friend of Mrs. Dane Calthrop, who asks her to help in the investigation.

- Agnes Woddell: house parlourmaid at Symmington home, who is the second murder victim.

- Rose: the Symmingtons' cook; talks too much and is given to dramatics.

- Miss Ginch: Symmington's clerk, who quits her post after receiving a poison pen letter, Jerry Burton observes that she seems to be enjoying getting the poison pen letter.

- Reverend Caleb Dane Calthrop: local vicar, academic in his style, given to Latin quotes, understood by no one around him.

- Mrs Maud Dane Calthrop: the vicar's wife who tries to keep an eye on people. She calls her friend Miss Marple for help when the situation in town worsens with murders and poison pen letters.

- Mr Pye: resident of Lymstock who enjoys the scandal raised by the poison pen letters. He collects antiques, and is described by his neighbours as effeminate.

- Colonel Appleton: resident of Combeacre, a village about 7 miles from Lymstock. He is intrigued by Joanna Burton and admires the beautiful Elsie Holland.

- Mrs Cleat: woman who lives in Lymstock, described as the local witch. She is the first person assumed by townspeople to be the writer of the poison pen letters, but she turns out to have no involvement.

Literary significance and reception

Maurice Willson Disher in The Times Literary Supplement of 19 June 1943 was mostly positive, starting, "Beyond all doubt the puzzle in The Moving Finger is fit for experts" and continued "The author is generous with her clues. Anyone ought to be able to read her secret with half an eye – if the other one-and-a-half did not get in the way. There has rarely been a detective story so likely to create an epidemic of self indulgent kicks." However, some reservations were expressed: "Having expended so much energy on her riddle, the author cannot altogether be blamed for neglecting the other side of her story. It would grip more if Jerry Burton, who tells it, was more credible. He is an airman who has crashed and walks with the aid of two sticks. That he should make a lightning recovery is all to the good, but why, in between dashing downstairs two at a time and lugging a girl into a railway carriage by main force, should he complain that it hurts to drive a car? And why, since he is as masculine in sex as the sons of King Gama does he think in this style, "The tea was china and delicious and there were plates of sandwiches and thin bread and butter and a quantity of little cakes"? Nor does it help verisimilitude that a bawling young female gawk should become an elegant beauty in less than a day."[7]

Maurice Richardson in The Observer wrote: "An atmosphere of perpetual, after-breakfast well-being; sherry parties in a country town where nobody is quite what he seems; difficult slouching daughters with carefully concealed coltish charm; crazy spinsters, of course; and adulterous solicitors. Agatha Christie is at it again, lifting the lid off delphiniums and weaving the scarlet warp all over the pastel pouffe." And he concluded, "Probably you will call Mrs Christie's double bluff, but this will only increase your pleasure."[4]

An unnamed reviewer in the Toronto Daily Star of 7 November 1942 said, "The Moving Finger has for a jacket design a picture of a finger pointing out one suspect after another and that's the way it is with the reader as chapter after chapter of the mystery story unfolds. It is not one of [Christie's] stories about her famous French [sic] detective, Hercule Poirot, having instead Miss Marple, a little old lady sleuth who doesn't seem to do much but who sets the stage for the final exposure of the murderer."[3]

The writer and critic Robert Barnard wrote "Poison pen in Mayhem Parva, inevitably leading to murder. A good and varied cast list, some humour, and stronger than usual romantic interest of an ugly-duckling-into-swan type. One of the few times Christie gives short measure, and none the worse for that."[5]

In the "Binge!" article of Entertainment Weekly of December 2014 – January 2015, the writers picked The Moving Finger as a Christie favourite on the list of the "Nine Great Christie Novels".[8]

Adaptations

Television

The Moving Finger was first adapted for television by the BBC in two episodes with Joan Hickson in the series Miss Marple. It first aired on 21 and 22 February 1985.[9][10] The adaptation is generally faithful to the novel, apart from making changes to names: the village of Lymstock became Lymston, Mona and Richard Symmington were renamed Angela and Edward Symmington and their sons Colin and Brian were renamed Robert and Jamie, Aimee Griffith became Eryl Griffith and had a much meeker personality, the characters of Agnes and Beatrice were combined and Miss Marple was brought into the story sooner than the novel does.

A second television adaptation was made with Geraldine McEwan as Miss Marple in the TV series, Agatha Christie's Marple and was filmed in Chilham, Kent.[11] It first aired on 12 February 2006.[12] This adaptation changes the personality of Jerry. The story is set a little later than in the novel, as mentioned in a review of the episode: "Miss Marple, observing the tragic effects of these missives on relationships and reputations, is practically in the background in this story, watching closely as a nihilistic young man (James D'Arcy) comes out of his cynical, alcohol-laced haze to investigate the source of so much misery." and is "set shortly after World War II."[13]

A third adaptation came as part of the French television series Les Petits Meurtres d'Agatha Christie. The episode aired in 2009.

A fourth adaptation was developed in Korea as part of the 2018 television series Ms. Ma, Nemesis.

Radio

A radio adaptation was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in May 2001 in the Saturday Play slot, starring June Whitfield as Miss Marple.[14]

Publication history

The work is dedicated to Christie's friends, the artist Mary Winifrid Smith and her husband Sidney Smith, an Assyriologist:[15]

To my Friends

Sydney and Mary Smith

Editions include:

- 1942, Dodd Mead and Company (New York), July 1942, Hardcover, 229 pp

- 1943, Collins Crime Club (London), June 1943, Hardcover, 160 pp

- 1948, Avon Books, Paperback, 158 pp (Avon number 164)

- 1948, Pan Books, Paperback, 190 pp (Pan number 55)

- 1953, Penguin Books, Paperback, 189 pp (Penguin number 930)

- 1961, Fontana Books (Imprint of HarperCollins), Paperback, 160 pp

- 1964, Dell Books, Paperback, 189 pp

- 1968, Greenway edition of collected works (William Collins), Hardcover, 255 pp

- 1968, Greenway edition of collected works (Dodd Mead), Hardcover, 255 pp

- 1970, Ulverscroft Large-print Edition, Hardcover, 331 pp; ISBN 0-85456-670-8

- 2005, Marple Facsimile edition (Facsimile of 1943 UK first edition), 12 September 2005, Hardcover; ISBN 0-00-720845-6

The novel's first true publication was the US serialisation in Collier's Weekly in eight instalments from 28 March (Volume 109, Number 13) to 16 May 1942 (Volume 109, Number 20) with illustrations by Mario Cooper.

The UK serialisation was as an abridged version in six parts in Woman's Pictorial from 17 October (Volume 44, Number 1136) to 21 November 1942 (Volume 44, Number 1141) under the slightly shorter title of Moving Finger. All six instalments were illustrated by Alfred Sindall.

This novel is one of two to differ significantly in American editions (the other being Three Act Tragedy), both hardcover and paperback. Most American editions of The Moving Finger have been abridged by about 9000 words to remove sections of chapters, and strongly resemble the Collier's serialisation which, mindful of the need to bring the magazine reader into the story quickly, begins without the leisurely introduction to the narrator's back-story that is present in the British edition, and lacks much of the characterisation throughout.

Christie admitted that this book was one of her favourites, stating, "I find that another [book] I am really pleased with is The Moving Finger. It is a great test to re-read what one has written some seventeen or eighteen years before. One's view changes. Some do not stand the test of time, others do."[16]

References

- ^ a b "The Classic Years: 1940 – 1944". American Tribute to Agatha Christie. May 2007. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ a b Peers, Chris; Spurrier, Ralph; Sturgeon, Jamie (March 1999). Collins Crime Club – A checklist of First Editions (Second ed.). Dragonby Press. p. 15.

- ^ a b c d "Review". Toronto Daily Star. 7 November 1942. p. 9.

- ^ a b Richardson, Maurice (13 June 1943). "Review". The Observer. p. 3.

- ^ a b Barnard, Robert (1990). A Talent to Deceive – an appreciation of Agatha Christie (Revised ed.). Fontana Books. p. 197. ISBN 0-00-637474-3.

- ^ Christie, Agatha (1942). The Moving Finger. p. Chapter 3.

- ^ Disher, Maurice Willson (19 June 1943). "Review". The Times Literary Supplement. p. 297.

- ^ "Binge! Agatha Christie: Nine Great Christie Novels". Entertainment Weekly. No. 1343–44. 26 December 2014. pp. 32–33.

- ^ The Moving Finger Part 1 (1985) at IMDb

- ^ The Moving Finger Part 2 (1985) at IMDb

- ^ Kent Film Office (4 February 2006). "Kent Film Office Miss Marple – The Moving Finger Film Focus". Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ Marple: The Moving Finger (2006) at IMDb

- ^ "Agatha Christie's Marple: Series 2, Editorial Reviews". Amazon. 5 August 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ^ "The Moving Finger". BBC Radio 4. 5 May 2001. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ "Mary Winifrid Smith: an artist lost in Mesopotamia". Art UK. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ Christie, Agatha (1977). An Autobiography. Collins. p. 520. ISBN 0-00-216012-9.

External links

- The Moving Finger at the official Agatha Christie website

- The Moving Finger (1985) at IMDb

- Marple: The Moving Finger (2006) at IMDb