The Bottle (etchings)

The Bottle is a series of eight etchings by British caricaturist George Cruikshank published in 1847. The etchings depict a family brought to ruin by alcohol. It was inspired by William Hogarth's' Rake's Progress.

The Bottle was very popular, selling 100,000 copies within days of its first printing, and was adapted into several plays and a novel.[1] It was followed by a sequel, The Drunkard's Children (1848), consisting of another eight plates.

Background

George Cruikshank began his career around 1809 as a caricaturist and graphic satirist, later focusing on book illustration, with his illustrations of works by Charles Dickens being among his best remembered work today. Beginning around 1845, Cruikshank entered into the final "temperance phase" of his career, lasting until his death in 1878. During this period, his work evinced an ardent support for the temperance movement. The Bottle and its successor, The Drunkard's Children, are the best known of the works that Cruikshank produced during this period.[2]

Cruikshank had been a heavy drinker during his life, and his father, Isaac Cruikshank, had died during a drinking contest.[3] Cruikshank was not a teetotaler at the time he created The Bottle, though he became one shortly thereafter.[1]

Description

The first plate in the series depicts a prosperous family- consisting of a husband and wife and three children- enjoying a meal at home. The husband holds in his hands a bottle of liquor and a glass, and, according to the caption, invites his wife "just to take a drop". The room in which the first drawing is set is also the setting for most of the following plates, though the scene degrades by the gradual disappearance of the furnishings and decorations that lend the initial plate its aura of coziness and respectability.[1]

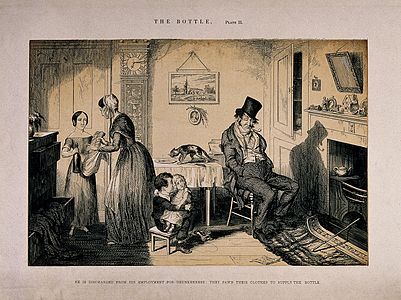

In the second plate, we are told the husband has lost his job, and the family must pawn their clothing to pay for alcohol. In plate 3, most of their furniture is seized to repay their debts. In plate 4, the family is reduced to begging for money on the streets, and by plate 5 we learn that the family's youngest child has died of "cold, misery, and want".

In plate 6, the husband strikes his wife, to the distress of their children. In plate 7, the wife lies dead, apparently killed by the husband with a liquor bottle.

The final scene, set some years later, shows the husband, now "a hopeless maniac", being visited in a mad-house by his surviving son and daughter.[1] The caption says the son and daughter have been "brought... to vice and to the streets", which is further reinforced by their gaudy appearance.

A bottle of liquor appears as a recurring visual motif in every plate up to the seventh, in which it appears in pieces on the floor, having been used by the husband as a murder weapon.

- Eight plates of The Bottle with original captions

- (1) The bottle is brought out for the first time. The husband induces his wife 'Just to take a drop.'

- (2) He is discharged from his employment for drunkenness: They pawn their clothes to supply the bottle.

- (3) An execution[a] sweeps off the greater part of their furniture. They comfort themselves with the bottle.

- (4) Unable to obtain employment, they are driven by poverty into the streets to beg, and by this means they still supply the bottle.

- (5) Cold, misery and want destroy their youngest child: They console themselves with the bottle.

- (6) Fearful quarrels and brutal violence are the natural consequences of the frequent use of the bottle.

- (7) The husband, in a state of furious drunkenness, kills his wife with the instrument of all their misery.

- (8) The bottle has done its work. It has destroyed the infant and the mother, it has brought the son and the daughter to vice and to the streets, and has left the father a hopeless maniac.

Analysis

Many observers have commented on the significance of the setting of the plates. Most are set in the same room (and even the asylum in the final plate echoes the layout of this room), though it radically transforms over time, in a way that mirrors the degradation of its inhabitants. In the first plate, the room is richly furnished with objects indicative of the family's security and respectability, including a painting of a church, an open cupboard stocked with china, a well-fed cat, and a number of figurines over the mantle.[4]

The changes to the objects on the mantle over the sequence are one indicator of the family's misfortune. In the second plate, the figurine of a man has tipped over, and in the third, the figurines of the man and woman have been replaced by a tankard. By the sixth plate, all that remains over the fireplace is a bottle and a glass.[4]

Further symbolism is found in the room's door. In the first plate, it is secured shut with a prominently displayed lock.[4] In the third plate, the door hangs open, exposing the room to the outside world, and in the fifth plate the door's lock plate is missing, replaced by a simple latch.

A small crack appears in the wall in the third plate, which widens in later scenes, exposing the building's inner structure.[5]

Impact

The Bottle was very popular, and has been described as possibly the greatest success of Cruikshank's career.[1] The initial printing of 100,000 copies of The Bottle apparently sold out within a few days.[1] It was cheaply produced using the technique of glyphography, and sold at the price of one shilling.[3][6] Finer reproductions were also sold for 6s and 2s 6d.[6]

The Bottle was dramatised around eight times,[1] including a dramatisation by Tom Taylor (credited "T. P. Taylor").[7] It inspired a penny novel,[1] poetry, sermons, magic lantern slides, and a variety of other merchandise.[6] Cruikshank did not control the copyright for the drawings, which allowed imitations and derivative works to flourish.[6]

- Comparison with unauthorized imitations

- Detail from Cruikshank's original third plate (1847).

- Detail from a reproduction which appeared in Timothy Shay Arthur's Temperance tales, or, six nights with the Washingtonians (1848). The copies are signed "Pilliner", and no credit was given to Cruikshank.[8]

- From an 1884 lithograph by M. Marques. The family's clothing and hairstyles have been updated to suit the times.

Notes

- ^ This is a now-dated sense of the word execution referring to the seizure of goods from a person in debt by a sheriff's officer.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h James, Louis (1978). "Cruikshank and Early Victorian Caricature". History Workshop. 6 (6): 107–120. doi:10.1093/hwj/6.1.107. JSTOR 4288194.

- ^ Steig, Michael (1975). "A Chapter of Noses: George Cruikshank's Psychonography of the Nose". Criticism. 17 (4): 308–325. JSTOR 23099570.

- ^ a b Mellby, Julie L. (13 April 2011). "More than 100,000 copies sold in the first few days". Graphic Arts.

- ^ a b c Allingham, Philip V. (7 August 2017). "Plate 1, "The Bottle. In Eight Plates" — George Cruikshank's cautionary Hogarthian progress (1847)". The Victorian Web. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ Allingham, Philip V. (9 August 2017). "Plate 5, "The Bottle. In Eight Plates" — George Cruikshank's cautionary Hogarthian progress (1847)". The Victorian Web. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d Paisana, Joanne (2004). "George Cruikshank and his bottle" (PDF). O Lago de Todos os Recursos (PDF). Universidade de Lisboa. Centro de Estudos Anglísticos (CEAUL). ISBN 972-8886-02-0.

- ^ Booth, MR (1964). "The Drunkard's Progress: Nineteenth-Century Temperance Drama" (PDF). The Dalhousie Review.

- ^ Railton, Stephen. "The Bottle (from Temperance Tales, 1848)". Uncle Tom's Cabin & American Culture. University of Virginia. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

![(3) An execution[a] sweeps off the greater part of their furniture. They comfort themselves with the bottle.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e8/A_drunken_man_sits_at_home_with_his_family_while_bailiffs_re_Wellcome_V0019403.jpg/411px-A_drunken_man_sits_at_home_with_his_family_while_bailiffs_re_Wellcome_V0019403.jpg)

![Detail from a reproduction which appeared in Timothy Shay Arthur's Temperance tales, or, six nights with the Washingtonians (1848). The copies are signed "Pilliner", and no credit was given to Cruikshank.[8]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6e/The_Bottle_3_family_detail_Pilliner.jpg/456px-The_Bottle_3_family_detail_Pilliner.jpg)