The Boat Race 1987

| 133rd Boat Race | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | 28 March 1987 | ||

| Winner | Oxford | ||

| Margin of victory | 4 lengths | ||

| Winning time | 19 minutes 59 seconds | ||

| Overall record (Cambridge–Oxford) | 69–63 | ||

| Umpire | Colin Moynihan (Oxford) | ||

| Other races | |||

| Reserve winner | Goldie | ||

| Women's winner | Cambridge | ||

| |||

The 133rd Boat Race took place on 28 March 1987. Held annually, the Boat Race is a side-by-side rowing race between crews from the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge along the River Thames. Oxford won by four lengths. The race featured the tallest, heaviest, youngest and oldest crew members in the event's history.

Oxford's crew rebelled in the prelude to the race, with several American rowers and the cox leaving the squad in February after their coach Dan Topolski removed their compatriot Chris Clark from the crew, replacing him with Scottish rower Donald Macdonald. The rebels were replaced in the main by the reserves. Umpired by former Oxford Blue Colin Moynihan, it was the first year that the race was sponsored by Beefeater Gin, replacing Ladbrokes after ten years.

In the 23rd reserve race, Cambridge's Goldie defeated Oxford's Isis by one length. Cambridge won the 42nd Women's Boat Race.

Background

History

The Boat Race is a side-by-side rowing competition between the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge (sometimes referred to as the "Dark Blues"[1] and the "Light Blues"[1] respectively). First held in 1829, the race takes place on the 4.2-mile (6.8 km) Championship Course on the River Thames in southwest London.[2] The rivalry is a major point of honour between the two universities and is followed throughout the United Kingdom; the races are broadcast worldwide.[3][4] Cambridge went into the race as reigning champions, having won the 1986 race by seven lengths,[5] and led overall with 69 victories to Oxford's 62 (excluding the "dead heat" of 1877).[6] The 1987 race was the first race to be sponsored by Beefeater Gin.[7]

The first Women's Boat Race took place in 1927, but did not become an annual fixture until the 1960s. Up until 2014, the contest was conducted as part of the Henley Boat Races, but as of the 2015 race, it is held on the River Thames, on the same day as the men's main and reserve races.[8] The reserve race, contested between Oxford's Isis boat and Cambridge's Goldie boat has been held since 1965. It usually takes place on the Tideway, prior to the main Boat Race.[5]

Mutiny

Following defeat in the previous year's race, Oxford's first in eleven years, American Chris Clark was determined to gain revenge: "Next year we're gonna kick ass ... Cambridge's ass. Even if I have to go home and bring the whole US squad with me."[9] He recruited another four American post-graduates: three international-class rowers (Dan Lyons, Chris Huntington and Chris Penny) and a cox (Jonathan Fish),[10][11] in an attempt to put together the fastest Boat Race crew in the history of the contest.[12]

When you recruit mercenaries, you can expect some pirates.

Disagreements over the training regime of Dan Topolski, the Oxford coach, ("He wanted us to spend more time training on land than water!" lamented Lyons)[10] led to the crew walking out on at least one occasion, and resulted in the coach revising his approach.[14] A fitness test between Clark and Scottish former Blue Donald Macdonald (in which the American triumphed) resulted in a call for the Scotsman's removal; it was accompanied with a threat that the Americans would refuse to row should Macdonald remain in the crew.[14] As boat club president, Macdonald "had absolute power over selection" and after announcing that Clark would row on stroke side, his weaker side, Macdonald would row on the bow side and Briton Tony Ward was to be dropped from the crew entirely, the American contingent mutinied.[11] After considerable negotiation and debate, much of it conducted in the public eye, Clark, Penny, Huntington, Lyons and Fish were dropped and replaced by members of Oxford's reserve crew, Isis.[11]

Crews

Oxford's crew weighed an average of nearly 9 pounds (4.1 kg) a rower more than their opponents.[7] The race featured the tallest and heaviest (Oxford's stroke Gavin Stewart), youngest (Cambridge's Matthew Brittin) and oldest (Oxford's president Donald Macdonald) crew members in the event's history.[7] The Cambridge boat saw four returning Blues while Oxford welcomed back just one, in Macdonald. Oxford's coach was Topolski; his counterpart was Alan Inns.[7]

| Seat | Oxford |

Cambridge | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | College | Weight | Name | College | Weight | |

| Bow | Hugh M. Pelham | Christ Church | 13 st 9.5 lb | Ian R. Clarke | Fitzwilliam | 12 st 6.5 lb |

| 2 | Peter A. Gish | Oriel | 14 st 0 lb | Richard A. B. Spink | Downing | 14 st 0.5 lb |

| 3 | Tony D. Ward | Oriel | 13 st 9 lb | Nicholas J. Grundy | Jesus | 12 st 9 lb |

| 4 | Paul Gleeson | Hertford | 14 st 12 lb | Matthew J. Brittin | Robinson | 14 st 8.5 lb |

| 5 | Richard Hull | Oriel | 14 st 7.5 lb | Stephen M. Peel (P) | Downing | 13 st 8.5 lb |

| 6 | Donald H. M. Macdonald (P) | Mansfield | 13 st 13 lb | Jim S. Pew | Trinity | 14 st 13 lb |

| 7 | Tom A. D. Cadoux-Hudson | New College | 14 st 6 lb | Jim R. Garman | Lady Margaret Boat Club | 14 st 2 lb |

| Stroke | Gavin B. Stewart | Wadham | 16 st 7 lb | Paddy H. Broughton | Magdalene | 14 st 1 lb |

| Cox | Andy D. Lobbenberg | Balliol | 8 st 3 lb | Julian M. Wolfson | Pembroke | 8 st 12 lb |

| Source:[7] (P) – boat club president | ||||||

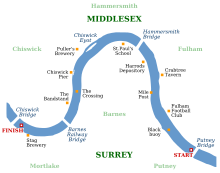

Race

With a more experienced crew and less disruption in the preparation for the race, Cambridge were considered favourites.[7] Oxford won the toss and elected to start from the Middlesex station.[15] A malfunction to umpire Colin Moynihan's barge caused a delay to the start; as a consequence the crews avoided racing in a lightning storm. Straight from the start, Oxford steered towards Middlesex to seek shelter from the inclement weather. Cambridge eventually followed, taking on water, and receiving warnings for encroaching into Oxford's water.[15] Almost a length ahead by Craven Cottage, Oxford steered across and in front of Cambridge to control the race before the Mile Post. A seven-second advantage at Hammersmith Bridge became twelve seconds by Barnes Bridge and remained so by the finishing post, with Oxford winning by four lengths in a time of 19 minutes 59 seconds.[15]

In the reserve race, Cambridge's Goldie beat Oxford's Isis by one length, their first victory in three years.[5] Cambridge won the 42nd Women's Boat Race, their fourth victory in six years.[5]

Reaction

Oxford's Macdonald was triumphant: "It was a fairy-tale."[15] Topolski acknowledged his crew's luck in winning the toss combined with the conditions: "We had been praying for rough water."[16] He also appeared conciliatory: "I wish the Americans had been there. It has nothing to do with vindication. We just won the race, that's all."[11] Cadoux-Hudson said, "I thought Cambridge would murder us but we took 20 colossal strokes and there was a primeval scream from the crew. There was a huge release."[11]

Legacy

In 1989 Topolski and author Patrick Robinson's book about the events, True Blue: The Oxford Boat Race Mutiny, was published. Seven years later, a film based on the book was released. Alison Gill, the then-president of the Oxford University Women's Boat Club wrote The Yanks in Oxford, in which she defended the Americans and claimed Topolski wrote True Blue in order to justify his own actions.[14] The journalist Christopher Dodd described True Blue as "particularly offensive".[11]

Oxford's stroke Gavin Stewart, writing in The Times in 1996, had chosen to mutiny because "Macdonald as president had lost the respect of the squad and the selection system had lost credibility".[14] In 2003, Clark had "broken his silence", stating "Mutiny is such a loaded term ... Rebellion would be a more apt description. On the face of it, I have no regrets whatsoever. However, I now lament my own personal maturity level. In hindsight my callowness had the effect of exacerbating a complicated but manageable situation."[9] On the twentieth anniversary of the race, Topolski insisted "It was just a selection dispute, an argument which every club in every sport has from time to time. The media just took the story and hyped it up."[9]

Clark, by 2023 the head coach of the Wisconsin Badgers men’s rowing programme, would conclude that he had learnt things from the experience that helped his own coaching and said that: “The entire thing was unnecessary,” admitting “I purposely never really talk much about it, only because it’s painful…it was so odd and like it or not, I was the central figure in it.” Whilst maintaining there was a “vacuum of leadership”, “no professional coaching staff”, and “no central authority…I certainly didn’t understand how much power the President had,” he said he personally held “no grudge whatsoever, If you’re going to throw a giant rock in a pool you’ve got to expect the wakes that are going to come. I understand Dan was personally hurt by it and I wish that wouldn’t have happened”.[17]

References

- ^ a b "Dark Blues aim to punch above their weight". The Observer. 6 April 2003. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ Smith, Oliver (25 March 2014). "University Boat Race 2014: spectators' guide". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "Former Winnipegger in winning Oxford–Cambridge Boat Race crew". CBC News. 6 April 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ "TV and radio". The Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Boat Race – Results". The Boat Race Company. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ "Classic moments – the 1877 dead heat". The Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Railton, Jim (28 March 1987). "Ill wind plagues Blues of 1987". The Times. No. 62728. p. 42.

- ^ "A brief history of the Women's Boat Race". The Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ a b c Baker, Andrew (6 April 2007). "When mutineers hit the Thames". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ a b Plummer, William (23 February 1987). "Oxford's U.S. Rowers Jump Ship, Leaving the Varsity Without All Its Oars in the Water". People. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Dodd, Christopher (July 2007). "Unnatural selection". Rowing News. pp. 54–63.

- ^ Roberts, Glenys (28 March 1987). "Mutiny in the boathouse". The Times. No. 62728. p. 11.

- ^ Moag, Jeff (May 2006). "Melting Pot". Rowing News. p. 40.

- ^ a b c d Johnston, Chris (25 November 1996). "Mutiny on the Isis". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d Railton, Jim (30 March 1987). "Oxford's gamblers gambol to flying fairy-tale finish". The Times. No. 62729. p. 34.

- ^ Miller, David (30 March 1987). "Oxford's win is a triumph for ethics". The Times. No. 62729. p. 36.

- ^ Mainland, Fergus (24 March 2023). "The Boat Race 'mutiny': As told by the 'villain' himself". Junior Rowing News. Retrieved 26 March 2023.