Thalattosauria

| Thalattosauria Temporal range: Middle-Late Triassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

| A collage of thalattosaur fossils. Clockwise from upper left: Askeptosaurus italicus (an askeptosauroid), Endennasaurus acutirostris (an askeptosauroid), Gunakadeit joseeae (a thalattosauroid), Thalattosaurus alexandrae (a thalattosauroid) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Neodiapsida |

| Order: | †Thalattosauria Merriam, 1904 |

| Superfamilies | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Thalattosauria (Greek for "sea lizards") is an extinct order of marine reptiles that lived in the Middle to Late Triassic. Thalattosaurs were diverse in size and shape, and are divided into two superfamilies: Askeptosauroidea and Thalattosauroidea. Askeptosauroids were endemic to the Tethys Ocean, their fossils have been found in Europe and China, and they were likely semiaquatic fish eaters with straight snouts and decent terrestrial abilities.[1] Thalattosauroids were more specialized for aquatic life and most had unusual downturned snouts and crushing dentition. Thalattosauroids lived along the coasts of both Panthalassa and the Tethys Ocean, and were most diverse in China and western North America.[2] The largest species of thalattosaurs grew to over 4 meters (13 feet) in length, including a long, flattened tail utilized in underwater propulsion. Although thalattosaurs bore a superficial resemblance to lizards, their exact relationships are unresolved. They are widely accepted as diapsids, but experts have variously placed them on the reptile family tree among Lepidosauromorpha (squamates, rhynchocephalians and their relatives),[3][4] Archosauromorpha (archosaurs and their relatives),[5] ichthyosaurs,[6] and/or other marine reptiles.[7][8]

Description

Thalattosaurs have moderate adaptations to marine lifestyles, including long, paddle-like tails and slender bodies with more than 20 dorsal vertebrae. There are few unique traits of the postcranial skeleton shared by all thalattosaurs, but the skeleton is still useful for distinguishing between askeptosauroids and thalattosauroids. Askeptosauroids are characterized by elongated necks with short neural spines and at least 11 vertebrae, while thalattosauroids have shorter necks sometimes involving as few as four vertebrae. Thalattosauroids also have tall neural spines on their neck, back, and especially the tail vertebrae, increasing the surface area for swimming via lateral undulation. Thalattosauroids additionally possess short, wide limb bones poorly adapted for movement on land. In this superfamily, the humerus is widest near the shoulder, the femur is widest near the knee, the radius is reniform ("kidney-shaped"), and phalanges are long and plate-like. Askeptosauroids retain hourglass-shaped limb bones like land reptiles, but even they share specializations with thalattosauroids such as a short tibia and fibula, with the latter expanding near the ankle.[1][9][2]

Skull

Thalattosaurs are diapsid reptiles, meaning that they have temporal fenestrae, two holes in the head behind the orbit (eye socket). However, many thalattosaurs have a vestigial upper temporal fenestra which is slit-like, and some have it fully closed up by surrounding bones.[10] Thalattosaurs lack a quadratojugal bone, leaving the lower temporal fenestra open from below. They also lack postparietal and tabular bones, while the squamosal bone is small, the supratemporal bone is extensive, and the quadrate bone is large. When seen from above, the rear edge of the skull bears a large, triangular embayment that reaches further forwards than the quadrates.[5]

Thalattosaurs have a rostrum (snout) significantly longer than the portion of the skull behind the eyes. A majority of this length is formed from the premaxillary bones, and the nares (nostril holes) are shifted back close to the eyes. The premaxillae stretch back very far and are incised into the frontal bones. This leads to an unusual trait that is characteristic of thalattosaurs, where the left and right nasal bones are separated from each other and restricted to a small portion of the snout near the nares. The lacrimal bone is typically lost or fused to the large crescent-shaped prefrontal bone in front of the orbit, mirroring the postfrontal bone which is usually fused to the three-pronged postorbital bone behind the orbit.[10][11][5]

Askeptosauroidea have narrow, straight-edged snouts which are often elongated and filled with conical teeth. One askeptosauroid, Endennasaurus, is entirely toothless[12] while another, Miodentosaurus, has a short, blunt snout.[13] Most members of the second thalattosaur group, Thalattosauroidea, have more distinctive downturned snouts. Clarazia and Thalattosaurus both have snouts that taper into a narrow tip. Most of the snout is straight, but premaxillae at the tip are downturned. Xinpusaurus and Concavispina also have downturned premaxillae, but the end of the maxillae are sharply upturned, forming a notch in their skull. In Hescheleria (and potentially Nectosaurus and Paralonectes), the premaxillae are abruptly downturned at the end of the snout, nearly forming a right angle with the rest of the jaw. In these forms, the end of the snout is a toothy hook separated from the rest of the jaw by a space called a diastema. Thalattosauroids also have heterodont dentition, with pointed piercing teeth at the front of the snout and low crushing teeth further back.[11] The exception to this rule is Gunakadeit, which has a straight snout and many slender teeth.[2] Thalattosaurs often have a pronounced retroarticular process at the rear of the mandible. Thalattosauroids are more specialized than askeptosauroids in jaw anatomy, as they have evolved a large peak-like coronoid bone and an angular bone that extends far forwards along the lower edge of the jaw. Palatal dentition is extensive in thalattosauroids but absent in askeptosauroids.[14][2]

Paleobiology

Thalattosaurs are only known from marine deposits, indicating that they were all primarily aquatic reptiles. The retracted nostrils and long, paddle-shaped tail are further evidence for aquatic habits. Thalattosauroids seemingly spent all of their time in the water, with short, wide limbs, poorly developed wrist and ankle bones, and tall vertebrae adapted for swimming via lateral undulation. Even so, they retained strong claws and functional digits which had not transformed into flippers, in contrast to ichthyosaurs and sauropterygians. Unlike these other marine reptiles, there is no evidence that thalattosaurs fully adapted to a pelagic life out in the open ocean, and instead they probably all lived in warm waters close to the coast. Askeptosauroids had stronger limbs more typical of terrestrial reptiles, indicating they would have been capable of moving around on land to some extent. They likely primarily used their tails when swimming, while thalattosauroids may have utilized their body and tail in conjunction.[3][1][12][2][15]

Thalattosaurs had diverse diets, though they probably all involved marine animals in one way or another. Endennasaurus probably predated small animals like fish fry or small crustaceans due to its lack of teeth.[12] Various thalattosauroids (like Thalattosaurus, Xinpusaurus, and Concavispina) had large fang-like teeth at the front of the mouth and thick button-like teeth at the back of the mouth. Based on Massare (1987)'s[16] technique of correlating diet with tooth shape, the taller teeth were suited for a "crunching" diet, involving armored fish, large crustaceans, and thin-shelled ammonites. The low, robust teeth would have been useful for a "crushing" diet specialized in large molluscs or other thick-shelled prey.[14][17] Gunakadeit's slender teeth correlated with the "Pierce II" guild of Massare (1987), indicating it likely fed on soft, fast-moving fish and squid. It also had a large hyoid apparatus which may have played a role in suction feeding.[2] Thalattosaurs also fell prey to other marine reptiles: the torso of a ~4 meter (13 feet) long Xinpusaurus xingyiensis has been found within the body cavity of a 5-meter (16 feet) long skeleton of the predatory ichthyosaur Guizhouichthyosaurus. This is the oldest known predatory interaction between marine reptiles, and Xinpusaurus may also be the largest prey item preserved within another marine reptile.[18]

Distribution

It is not certain where thalattosaurs originated from. During the Triassic period, the earth had one giant supercontinent, Pangaea, which was surrounded by the superocean Panthalassa. The eastern portion of Pangaea was incised by a massive tropical inland sea, the Tethys Ocean, which extended all the way from China to Western Europe. While thalattosauroids are known from worldwide Triassic marine deposits, askeptosauroids are only known in Tethyan deposits. Assuming Endennasaurus and Askeptosaurus were the most basal askeptosauroids, Askeptosauroidea would have originated in the Western Tethys Ocean, now the Alpine region of Europe.[1] However, if Miodentosaurus is more basal, a Western Tethys (European) origin would be significantly less likely.[19] Although the sister group to Thalattosauria is still debated, one possibility, the icthyosauromorphs, seemingly evolved in the Eastern Tethys (China) during the early Triassic or earlier.[8]

The oldest known thalattosauroids (Thalattosaurus, Paralonectes, and Agkistrognathus of British Columbia's Sulphur Mountain Formation) lived in eastern Panthalassa, along what is now the western coast of North America. Müller (2005, 2007) argued that at least one branch of thalattosauroids had managed to spread worldwide early in their evolution.[1][20] However, this is based on the hypothesis that Nectosaurus (from California), Xinpusaurus (from China), and an unnamed species from Austria formed a clade basal to other thalattosaurs, a classification scheme which contrasts with many other studies.[9] The worldwide distribution of Thalattosauroidea is intriguing considering that thalattosaurs are considered to be poorly adapted for traversing open oceans, which would have been a necessity for spreading between the eastern coast of Panthalassa and the Tethys Ocean.[20] Coastal "refuges" such as volcanic island arcs and guyots may have facilitated the ability of thalattosaurs to spread between ocean basins.[10] Hescheleria-like forms were previously only reported from North America and Europe,[21] but in 2021 a Hescheleria-like snout fragment was reported from China, indicating that they also had a widespread distribution.[22] Trans-Panthalassa connections are also observed in other Triassic marine life such as pistosaurs and ammonites.[10] Evidently thalattosaurs were capable of dispersing throughout major marine regions multiple times before the group's extinction, with thalattosauroids likely more prolific at spreading than askeptosauroids due to their greater aquatic adaptations.[2]

Classification

Early hypotheses

When first named by Merriam in 1904, Thalattosauria was only known by the species Thalattosaurus alexandrae. Based primarily on the overall skull shape, it was hypothesized to have been close to the reptile order Rhynchocephalia, which includes Sphenodon (the living tuatara). Nevertheless, Thalattosaurus was recognized as distinct enough to be given its own order, and was tentatively grouped along with Rhynchocephalia in the group Diaptosauria, a collection of various "primitive" reptiles now known to be polyphyletic. Within Diaptosauria, thalattosaurs were also considered very closely related to choristoderes and "Proganosauria" (parareptiles). Comparisons were also made with Parasuchia (phytosaurs), Lacertilia (lizards), and Proterosuchus, but dismissed as incompatible with proposed evolutionary schemes.[23]

Further discussion by Merriam (1905) considered a relationship with ichthyosaurs due to their similar ecology, but questioned why their skull and vertebral anatomy would diverge so widely if they had a close common ancestor. He proposed that potential similarities were best explained as convergent evolution. The possibility that thalattosaurs diverged from reptiles close to lizards (such as Paliguana) was described in more detail, with thalattosaurs serving as a short-lived early attempt for near-lizards to return to the sea, an evolutionary process later repeated more successfully when mosasaurs evolved from true lizards. Nevertheless, Merriam found no clear evidence that any previously known reptile group was directly ancestral to thalattosaurs or vice versa. They were probably descended from land-dwelling Permian reptiles, and not closely related to other marine reptile groups which first evolved in the Triassic.[3] Later 20th-century workers typically placed thalattosaurs close to rhynchocephalians or squamates as part of the group now known as Lepidosauromorpha.[14]

Modern classification and external relationships

The rising popularity of cladistics in the late 1980s had some effects on thalattosaur classification. Continued research has helped cement some aspects of reptile classification, such as how Sauria (a major clade of diapsids including all living reptiles) split in the Permian into two branches: Lepidosauromorpha (which leads to lizards, snakes, and the tuatara) and Archosauromorpha (which leads to crocodilians and dinosaurs, including birds). While many paleontologists still consider thalattosaurs probable lepidosauromorphs, a few studies (such as a phylogenetic analysis by Evans, 1988) have instead suggested that they may be on the archosauromorph branch of Sauria.[5] Rieppel (1998)'s re-evaluation of the thalattosaur-like pachypleurosaur Hanosaurus argued that thalattosaurs have affinities with the aquatic reptile order Sauropterygia, which itself is aligned with turtles within an expansive interpretation of Lepidosauromorpha.[4]

An analysis by Müller (2004) has even considered thalattosaurs to belong just outside of Sauria. Unusually, thalattosaurs have an affinity to shift near ichthyosaurs (in the group Ichthyosauromorpha) when certain basal saurians or near-saurians are excluded from the data set.[6] Some analyses derived from Müller (2004) group thalattosaurs in a "marine superclade" with ichthyosauromorphs and sauropterygians, and sometimes with turtles, archosauromorphs, or lepidosauromorphs as well. For example, Simões et al (2022) classify thalattosaurs as the sister group of the sauropterygians, with their clade being sister to the ichthyosauromorphs, and all three being basal archosauromorphs. However, cladograms generated by these analyses change in unpredictable ways through alterations to their methodology (such as including or excluding aquatic adaptations or switching between parsimony and bayesian inference), leading some to have concerns over the validity of the "marine superclade".[7][8][24][25][26] While thalattosaurs are almost certainly diapsids, the large degree of uncertainty surrounding their outgroup relations has led most modern paleontologists to classify them as Diapsida incertae sedis.

Internal relationships

One of the first phylogenetic analyses specifically focusing on thalattosaurs was part of Nicholls (1999)'s reevaluation of Thalattosaurus and Nectosaurus. She used a restricted definition of Thalattosauria which referred to a clade including all reptiles more closely related to Nectosaurus and Hescheleria than to Endennasaurus or Askeptosaurus. The more inclusive group including Askeptosaurus, Endennasaurus, and traditional thalattosaurs was given the name Thalattosauriformes.[14][1][20]

However, most studies focusing on the group have preferred to retain a broader definition of Thalattosauria equivalent to Nicholls' Thalattosauriformes clade, including reptiles close to both Askeptosaurus and Thalattosaurus. In these studies, Thalattosauria is divided into two branches, one leading to relatives of Askeptosaurus and the other leading to relatives of Thalattosaurus. The clade containing reptiles closer to Thalattosaurus than to askeptosaurids is given the name Thalattosauroidea (and sometimes called Thalattosauridea[9][19]). Meanwhile, the clade containing reptiles closer to askeptosaurids is termed Askeptosauroidea[10][13][2] or Askeptosauridea.[9][19]

Subsequent studies since Nicholls (1999) started to include more taxa, including newly described Chinese taxa such as Anshunsaurus and Xinpusaurus.[10][27] However, uncertainty over Endennasaurus's thalattosaurian ancestry led to it being excluded from these analyses. After Müller et al. (2005) re-affirmed that Endennasaurus was closely related to Askeptosaurus,[12] all thalattosaurs known at the time were finally combined into phylogenetic analyses.[9][20] Studies by Rieppel, Liu, Cheng, Wu, and others continued to identify new Chinese taxa such as Miodentosaurus and various species of Anshunsaurus and Xinpusaurus, though homoplasy in these new taxa has led to little resolution in the structure of the two major branches of Thalattosauria.[13][28] In an attempt to remedy this problem, new phylogenetic analyses were developed by Liu et al. (2013) during the description of Concavispina,[19] and Druckenmiller et al. (2020) during the description of Gunakadeit.[2]

The internal relationships of thalattosaurs is still considered tentative and inconclusive, although the fundamental structure of the group (a monophyletic Thalattosauria clade split into askeptosauroids and thalattosauroids) is very stable. Some paleontologists have attempted to divide thalattosaurs into families. One family, Askeptosauridae, is typically considered to include Askeptosaurus and Anshunsaurus,[9] with a few studies also placing Miodentosaurus[13] or Endennasaurus[12] within it. Another family, Thalattosauridae, was originally used to group Thalattosaurus and Nectosaurus,[3] was later redefined to exclude Nectosaurus,[14] and later still encompassed practically all thalattosauroids.[19] Many thalattosaur-focused paleontologists avoid using family names due to their inconsistent usage and questionable validity.

The cladogram presented here is based on the largest and most recent analysis of thalattosaur ingroup relations, Druckenmiller et al. (2020). It shows all thalattosaur genera except for the fragmentary Agkistrognathus.[2]

| Thalattosauria | |

List of genera

Other thalattosaurs include unnamed or indeterminate species from the Kössen Formation of Austria,[20] the Sulphur Mountain[29] and Pardonet Formations[30] of British Columbia, the Natchez Pass Formation of Nevada,[30][21] and the Vester Formation of Oregon.[31][32] Blezingeria, a fragmentary marine reptile from the Muschelkalk of Germany, has also been considered a thalattosaur by some authors but this assignment is uncertain at best.[1] Neosinasaurus, a poorly-known reptiles from the Xiaowa Formation of China, has also been considered a thalattosaur.[13] Thalattosaurian fragments are known from Spanish Muschelkalk.[33] A previously unnamed specimen from Alaska[34] was described as Gunakadeit in 2020.[2]

| Name | Year | Formation | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agkistrognathus | 1993 | Sulphur Mountain Formation (Middle Triassic?) | A poorly-known thalattosauroid with strong jaws | ||

| Anshunsaurus | 1999 | Zhuganpo Formation, Xiaowa Formation (Middle Triassic-Late Triassic, Ladinian?-Carnian?) | A large askeptosauroid known from three species. One of the few thalattosaurs for which a growth series is known |

| |

| Askeptosaurus | 1925 | Grenzbitumenzone (Middle Triassic, Anisian?) | The namesake of Askeptosauroidea and one of the most well-known European thalattosaurs |

| |

| Clarazia | 1936 | Grenzbitumenzone (Middle Triassic, Anisian?) | A thalattosauroid related to Hescheleria |

| |

| Concavispina | 2013 | Xiaowa Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian?) | The largest known thalattosauroid, a close relative of Xinpusaurus |

| |

| Endennasaurus | 1984 | Zorzino Limestone (Late Triassic, Norian) | An unusual askeptosauroid with a pointed, toothless snout |

| |

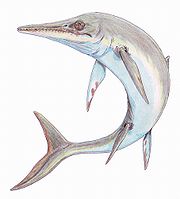

| Gunakadeit | 2020 | Hound Island Volcanics (Late Triassic, Norian) | A basal thalattosauroid, the most well-preserved specimen from North America |

| |

| Hescheleria | 1936 | Grenzbitumenzone (Middle Triassic, Anisian?) | A hook-snouted thalattosauroid | ||

| Miodentosaurus | 2007 | Xiaowa Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian?) | A very large askeptosauroid with a short snout |

| |

| Nectosaurus | 1905 | Hosselkus Limestone (Late Triassic) | One of the first thalattosaurs to be described, along with Thalattosaurus |

| |

| Paralonectes | 1993 | Sulphur Mountain Formation (Middle Triassic?) | A poorly-known thalattosauroid with a downcurved snout | ||

| Pachystropheus | 1935 | Westbury Formation (Late Triassic, Rhaetian) | A small askeptosauroid, youngest known thalattosaur.[35] | ||

| Wapitisaurus | 1988 | Sulphur Mountain Formation (Early Triassic) | A thalattosauroid initially described as a weigeltisaurid.[36] | ||

| Wayaosaurus | 2000 | "Wayao Member" (Late Triassic, Carnian?) | A large askeptosauroid similar to Miodentosaurus. Initially described as a pachypleurosaur.[37] | ||

| Thalattosaurus | 1904 | Hosselkus Limestone, Sulphur Mountain Formation (Middle Triassic-Late Triassic) | The namesake of Thalattosauria and the first genus to be described. Known from at least two species |

| |

| Xinpusaurus | 2000 | Zhuganpo Formation, Xiaowa Formation (Middle Triassic-Late Triassic, Ladinian?-Carnian?) | A thalattosauroid with an unusual notched skull. Known from four species, though not all may be valid |

|

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Müller, Johannes (2005). "The anatomy of Askeptosaurus italicus from the Middle Triassic of Monte San Giorgio, and the interrelationships of thalattosaurs (Reptilia, Diapsida)". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 42 (7): 1347–1367. Bibcode:2005CaJES..42.1347M. doi:10.1139/e05-030.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Druckenmiller, Patrick S.; Kelley, Neil P.; Metz, Eric T.; Baichtal, James (4 February 2020). "An articulated Late Triassic (Norian) thalattosauroid from Alaska and ecomorphology and extinction of Thalattosauria". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 1746. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.1746D. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-57939-2. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7000825. PMID 32019943.

- ^ a b c d Merriam, John C. (1905). "The Thalattosauria: a group of marine reptiles from the Triassic of California". Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences. 5 (1): 1–52.

- ^ a b c Rieppel, Olivier (1998-09-15). "The systematic status of Hanosaurus hupehensis (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) from the Triassic of China". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 18 (3): 545–557. Bibcode:1998JVPal..18..545R. doi:10.1080/02724634.1998.10011082. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ a b c d e Evans, Susan E. (1988). "The early history and relationships of the Diapsida". In Benton, M. J. (ed.). The Phylogeny and Classification of the Tetrapods, Volume 1: Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 221–260.

- ^ a b c Müller, Johannes (2004). "The relationships among diapsid reptiles and the influence of taxon selection". In Arratia, G; Wilson, M.V.H.; Cloutier, R. (eds.). Recent Advances in the Origin and Early Radiation of Vertebrates. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. pp. 379–408. ISBN 978-3-89937-052-2.

- ^ a b c Chen, Xiao-hong; Motani, Ryosuke; Cheng, Long; Jiang, Da-yong; Rieppel, Olivier (2014-07-11). "The Enigmatic Marine Reptile Nanchangosaurus from the Lower Triassic of Hubei, China and the Phylogenetic Affinities of Hupehsuchia". PLOS ONE. 9 (7): e102361. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j2361C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0102361. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4094528. PMID 25014493.

- ^ a b c Motani, Ryosuke; Jiang, Da-Yong; Chen, Guan-Bao; Tintori, Andrea; Rieppel, Olivier; Ji, Cheng; Huang, Jian-Dong (5 November 2014). "A basal ichthyosauriform with a short snout from the Lower Triassic of China". Nature. 517 (7535): 485–488. Bibcode:2015Natur.517..485M. doi:10.1038/nature13866. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 25383536. S2CID 4392798.

- ^ a b c d e f Liu, J.; Rieppel, O. (2005). "Restudy of Anshunsaurus huangguoshuensis (Reptilia: Thalattosauria) from the Middle Triassic of Guizhou, China" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3488): 1–34. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2005)488[0001:roahrt]2.0.co;2. ISSN 0003-0082. S2CID 55642315.

- ^ a b c d e f Rieppel, O.; Liu, J.; Bucher, H. (2000-09-25). "The first record of a thalattosaur reptile from the Late Triassic of southern China (Guizhou Province, PR China)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 20 (3): 507–514. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020[0507:TFROAT]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 140706921.

- ^ a b Rieppel, O.; Müller, J.; Liu, J. (2005). "Rostral structure in Thalattosauria (Reptilia, Diapsida)". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 42 (12): 2081–2086. Bibcode:2005CaJES..42.2081R. doi:10.1139/e05-076.

- ^ a b c d e Müller, Johannes; Renesto, Silvio; Evans, Susan E. (2005). "The marine diapsid reptile Endennasaurus from the Upper Triassic of Italy". Palaeontology. 48 (1): 15–30. Bibcode:2005Palgy..48...15M. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2004.00434.x. ISSN 1475-4983.

- ^ a b c d e Wu, Xiao-Chun; Cheng, Yen-Nien; Sato, Tamaki; Shan, Hsi-Yin (2009). "Miodentosaurus brevis Cheng et al. 2007 (Diapsida: Thalattosauria): Its postcranial skeleton and phylogenetic relationships". Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 47 (1): 1–20.

- ^ a b c d e Nicholls, Elizabeth L. (April 15, 1999). "A reexamination of Thalattosaurus and Nectosaurus and the relationships of the Thalattosauria (Reptilia: Diapsida)". PaleoBios. 19 (1): 1–29.

- ^ Xing, Lida; Klein, Hendrik; Lockley, Martin G.; Wu, Xiao-chun; Benton, Michael J.; Zeng, Rong; Romilio, Anthony (2020-11-15). "Footprints of marine reptiles from the Middle Triassic (Anisian-Ladinian) Guanling Formation of Guizhou Province, southwestern China: The earliest evidence of synchronous style of swimming". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 558: 109943. Bibcode:2020PPP...55809943X. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.109943. ISSN 0031-0182. S2CID 221866075.

- ^ Massare, Judy A. (1987-06-18). "Tooth morphology and prey preference of Mesozoic marine reptiles". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 7 (2): 121–137. Bibcode:1987JVPal...7..121M. doi:10.1080/02724634.1987.10011647. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Li, Zhi-Guang; Jiang, Da-Yong; Rieppel, Olivier; Motani, Ryosuke; Tintori, Andrea; Sun, Zuo-Yu; Ji, Cheng (2016-11-01). "A new species of Xinpusaurus (Reptilia, Thalattosauria) from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Xingyi, Guizhou, southwestern China". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (6): e1218340. Bibcode:2016JVPal..36E8340L. doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1218340. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 132418823.

- ^ Jiang, Da-Yong; Motani, Ryosuke; Tintori, Andrea; Rieppel, Olivier; Ji, Cheng; Zhou, Min; Wang, Xue; Lu, Hao; Li, Zhi-Guang (2020-09-25). "Evidence Supporting Predation of 4-m Marine Reptile by Triassic Megapredator". iScience. 23 (9): 101347. Bibcode:2020iSci...23j1347J. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101347. ISSN 2589-0042. PMC 7520894. PMID 32822565.

- ^ a b c d e Liu, J.; Zhao, L. J.; Li, C.; He, T. (2013). "Osteology of Concavispina biseridens (Reptilia, Thalattosauria) from the Xiaowa Formation (Carnian), Guanling, Guizhou, China". Journal of Paleontology. 87 (2): 341. Bibcode:2013JPal...87..341L. doi:10.1666/12-059R1.1. S2CID 83684967.

- ^ a b c d e Müller, Johannes (2007-03-12). "First record of a thalattosaur from the Upper Triassic of Austria". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (1): 236–240. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[236:FROATF]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 85938927.

- ^ a b Sues, Hans-Dieter; Clark, James (2005). "Thalattosaurs from the Late Triassic (Carnian) of Nevada and their paleobiogeographic significance" (PDF). SVP 65th Annual Meeting Abstracts of Papers.

- ^ Chai, Jun; Jiang, Da-Yong; Rieppel, Olivier; Motani, Ryosuke; Tintori, Andrea; Druckenmiller, Patrick (4 June 2021). "A New Specimen of Thalattosauroidea (Reptilia, Thalattosauriformes) from the Middle Triassic (Ladinian) of Xingyi, Southernwestern China". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 40 (6): e1881965. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1881965. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 233970875.

- ^ Merriam, John C. (1904). "A new marine reptile from the Triassic of California". University of California Department of Geology Bulletin. 3: 419–421.

- ^ Jiang, Da-Yong; Motani, Ryosuke; Huang, Jian-Dong; Tintori, Andrea; Hu, Yuan-Chao; Rieppel, Olivier; Fraser, Nicholas C.; Ji, Cheng; Kelley, Neil P.; Fu, Wan-Lu; Zhang, Rong (2016-05-23). "A large aberrant stem ichthyosauriform indicating early rise and demise of ichthyosauromorphs in the wake of the end-Permian extinction". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 26232. Bibcode:2016NatSR...626232J. doi:10.1038/srep26232. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4876504. PMID 27211319.

- ^ Scheyer, Torsten M.; Neenan, James M.; Bodogan, Timea; Furrer, Heinz; Obrist, Christian; Plamondon, Mathieu (2017-06-30). "A new, exceptionally preserved juvenile specimen of Eusaurosphargis dalsassoi (Diapsida) and implications for Mesozoic marine diapsid phylogeny". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 4406. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.4406S. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-04514-x. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5493663. PMID 28667331.

- ^ Simões, Tiago R.; Kammerer, Christian F.; Caldwell, Michael W.; Pierce, Stephanie E. (2022-08-19). "Successive climate crises in the deep past drove the early evolution and radiation of reptiles". Science Advances. 8 (33): eabq1898. Bibcode:2022SciA....8.1898S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abq1898. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 9390993. PMID 35984885.

- ^ Jiang, Da-Yong; Maisch, Michael W.; Sun, Yuan-Lin; Matzke, Andreas T.; Hao, Wei-Cheng (2004-03-25). "A new species of Xinpusaurus (Thalattosauria) from the Upper Triassic of China". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (1): 80–88. Bibcode:2004JVPal..24...80J. doi:10.1671/1904-7. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 84809090.

- ^ Cheng, Long; Chen, Xiaohong; Zhang, Baomin; Cai, Yongjian (2011). "New Study of Anshunsaurus huangnihensis Cheng, 2007 (Reptilia: Thalattosauria): Revealing its Transitional Position in Askeptosauridae". Acta Geologica Sinica - English Edition. 85 (6): 1231–1237. Bibcode:2011AcGlS..85.1231C. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2011.00584.x. ISSN 1755-6724. S2CID 129819570.

- ^ Nicholls, Elizabeth L.; Brinkman, Donald (March 1993). "New thalattosaurs (Reptilia: Diapsida) from the Triassic Sulphur Mountain Formation of Wapiti Lake, British Columbia". Journal of Paleontology. 67 (2): 263–278. Bibcode:1993JPal...67..263N. doi:10.1017/S0022336000032194. ISSN 0022-3360. S2CID 132095082.

- ^ a b Storrs, Glenn W. (1991-12-01). "Note on a second occurrence of thalattosaur remains (Reptilia: Neodiapsida) in British Columbia". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 28 (12): 2065–2068. Bibcode:1991CaJES..28.2065S. doi:10.1139/e91-186. ISSN 0008-4077.

- ^ Metz, Eric T.; Druckenmiller, Patrick S.; Carr, Gregory (2015). "A new thalattosaur from the Vester Formation (Carnian) of Central Oregon, USA". SVP 75th Annual Meeting Abstracts of Papers.

- ^ "Triassic Reptile Skewered Clams with Teeth on Roof of Its Mouth". Live Science. 13 November 2015.

- ^ Rieppel, O.; Hagdorn, H. (1998). "Fossil reptiles from the Spanish Muschelkalk (mont-ral and alcover, province Tarragona)". Historical Biology. 13 (1): 77–97. Bibcode:1998HBio...13...77R. doi:10.1080/08912969809386575.

- ^ Petersen, C. (13 July 2011). "Recent fossil discovery near Keku Strait a first for Alaska". Capital City Weekly. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ Quinn, Jacob G.; Matheau-Raven, Evangelos R.; Whiteside, David I.; Marshall, John E. A.; Hutchinson, Deborah J.; Benton, Michael J. (2024-06-04). "The relationships and paleoecology of Pachystropheus rhaeticus, an enigmatic latest Triassic marine reptile". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. doi:10.1080/02724634.2024.2350408. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Bastiaans, Dylan; Buffa, Valentin; Scheyer, Torsten M. (November 2023). "To glide or to swim? A reinvestigation of the enigmatic Wapitisaurus problematicus (Reptilia) from the Early Triassic of British Columbia, Canada". Royal Society Open Science. 10 (11). Bibcode:2023RSOS...1031171B. doi:10.1098/rsos.231171. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 10646446. PMID 38026014.

- ^ Chai, Jun; Lu, Hao; Jiang, Da-Yong; Motani, Ryosuke; Druckenmiller, Patrick S.; Tintori, Andrea; Kelley, Neil P. (2023-10-23). "Reidentification of Wayaosaurus bellus and the conservative trunk and tail shape of Thalattosauria". Historical Biology: 1–20. doi:10.1080/08912963.2023.2264886. ISSN 0891-2963.