Temporal dynamics of music and language

The temporal dynamics of music and language describes how the brain coordinates its different regions to process musical and vocal sounds. Both music and language feature rhythmic and melodic structure. Both employ a finite set of basic elements (such as tones or words) that are combined in ordered ways to create complete musical or lingual ideas.

Neuroanotomy of language and music

Key areas of the brain are used in both music processing and language processing, such as Brocas area that is devoted to language production and comprehension. Patients with lesions, or damage, in the Brocas area often exhibit poor grammar, slow speech production and poor sentence comprehension. The inferior frontal gyrus, is a gyrus of the frontal lobe that is involved in timing events and reading comprehension, particularly for the comprehension of verbs. The Wernickes area is located on the posterior section of the superior temporal gyrus and is important for understanding vocabulary and written language.

The primary auditory cortex is located on the temporal lobe of the cerebral cortex. This region is important in music processing and plays an important role in determining the pitch and volume of a sound.[1] Brain damage to this region often results in a loss of the ability to hear any sounds at all. The frontal cortex has been found to be involved in processing melodies and harmonies of music. For example, when a patient is asked to tap out a beat or try to reproduce a tone, this region is very active on fMRI and PET scans.[2] The cerebellum is the "mini" brain at the rear of the skull. Similar to the frontal cortex, brain imaging studies suggest that the cerebellum is involved in processing melodies and determining tempos. The medial prefrontal cortex along with the primary auditory cortex has also been implicated in tonality, or determining pitch and volume.[1]

In addition to the specific regions mentioned above many "information switch points" are active in language and music processing. These regions are believed to act as transmission routes that conduct information. These neural impulses allow the above regions to communicate and process information correctly. These structures include the thalamus and the basal ganglia.[2]

Some of the above-mentioned areas have been shown to be active in both music and language processing through PET and fMRI studies. These areas include the primary motor cortex, the Brocas area, the cerebellum, and the primary auditory cortices.[2]

Imaging the brain in action

The imaging techniques best suited for studying temporal dynamics provide information in real time. The methods most utilized in this research are functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI, and positron emission tomography known as PET scans.[3]

Positron emission tomography involves injecting a short-lived radioactive tracer isotope into the blood. When the radioisotope decays, it emits positrons which are detected by the machine sensor. The isotope is chemically incorporated into a biologically active molecule, such as glucose, which powers metabolic activity. Whenever brain activity occurs in a given area these molecules are recruited to the area. Once the concentration of the biologically active molecule, and its radioactive "dye", rises enough, the scanner can detect it.[3] About one second elapses from when brain activity begins to when the activity is detected by the PET device. This is because it takes a certain amount of time for the dye to reach the needed concentrations can be detected.[4]

Functional magnetic resonance imaging or fMRI is a form of the traditional MRI imaging device that allows for brain activity to be observed in real time. An fMRI device works by detecting changes in neural blood flow that is associated with brain activity. fMRI devices use a strong, static magnetic field to align nuclei of atoms within the brain. An additional magnetic field, often called the gradient field, is then applied to elevate the nuclei to a higher energy state.[5] When the gradient field is removed, the nuclei revert to their original state and emit energy. The emitted energy is detected by the fMRI machine and is used to form an image. When neurons become active blood flow to those regions increases. This oxygen-rich blood displaces oxygen depleted blood in these areas. Hemoglobin molecules in the oxygen-carrying red blood cells have different magnetic properties depending on whether it is oxygenated.[5] By focusing the detection on the magnetic disturbances created by hemoglobin, the activity of neurons can be mapped in near real time.[5] Few other techniques allow for researchers to study temporal dynamics in real time.

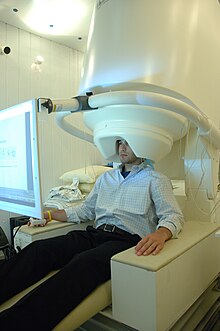

Another important tool for analyzing temporal dynamics is magnetoencephalography, known as MEG. It is used to map brain activity by detecting and recording magnetic fields produced by electrical currents generated by neural activity. The device uses a large array of superconducting quantum interface devices, called SQUIDS, to detect magnetic activity. Because the magnetic fields generated by the human brain are so small the entire device must be placed in a specially designed room that is built to shield the device from external magnetic fields.[5]

Other research methods

Another common method for studying brain activity when processing language and music is transcranial magnetic stimulation or TMS. TMS uses induction to create weak electromagnetic currents within the brain by using a rapidly changing magnetic field. The changes depolarize or hyper-polarize neurons. This can produce or inhibit activity in different regions. The effect of the disruptions on function can be used to assess brain interconnections.[6]

Recent research

Many aspects of language and musical melodies are processed by the same brain areas. In 2006, Brown, Martinez and Parsons found that listening to a melody or a sentence resulted in activation of many of the same areas including the primary motor cortex, the supplementary motor area, the Brocas area, anterior insula, the primary audio cortex, the thalamus, the basal ganglia and the cerebellum.[7]

A 2008 study by Koelsch, Sallat and Friederici found that language impairment may also affect the ability to process music. Children with specific language impairments, or SLIs were not as proficient at matching tones to one another or at keeping tempo with a simple metronome as children with no language disabilities. This highlights the fact that neurological disorders that effect language may also affect musical processing ability.[8]

Walsh, Stewart, and Frith in 2001 investigated which regions processed melodies and language by asking subjects to create a melody on a simple keyboard or write a poem. They applied TMS to the location where musical and lingual data. The research found that TMS applied to the left frontal lobe had affected the ability to write or produce language material, while TMS applied to the auditory and Brocas area of the brain most inhibited the research subject's ability to play musical melodies. This suggests that some differences exist between music and language creation.[9]

Developmental aspects

The basic elements of musical and lingual processing appear to be present at birth. For example, a French 2011 study that monitored fetal heartbeats found that past the age of 28 weeks, fetuses respond to changes in musical pitch and tempo. Baseline heart rates were determined by 2 hours of monitoring before any stimulus. Descending and ascending frequencies at different tempos were played near the womb. The study also investigated fetal response to lingual patterns, such as playing a sound clip of different syllables, but found no response to different lingual stimulus. Heart rates increased in response to high pitch loud sounds compared to low pitched soft sounds. This suggests that the basic elements of sound processing, such as discerning pitch, tempo and loudness are present at birth, while later-developed processes discern speech patterns after birth.[10]

A 2010 study researched the development of lingual skills in children with speech difficulties. It found that musical stimulation improved the outcome of traditional speech therapy. Children aged 3.5 to 6 years old were separated into two groups. One group heard lyric-free music at each speech therapy session while the other group was given traditional speech therapy. The study found that both phonological capacity and the children's ability to understand speech increased faster in the group that was exposed to regular musical stimulation.[11]

Applications in Rehabilitation

Recent studies found that the effect of music in the brain is beneficial to individuals with brain disorders.[12][13][14][15] Stegemöller discusses the underlying principles of music therapy being increased dopamine, neural synchrony and lastly, a clear signal which are important features for normal brain functioning.[15] This combination of effects induces the brain's neuroplasticity which is suggested to increase an individual's potential for learning and adaptation.[16] Existing literature examines the effect of music therapy on those with Parkinson's disease, Huntington's Disease and Dementia among others.

Parkinson's disease

Individuals with Parkinson's disease experience gait and postural disorders caused by decreased dopamine in the brain.[17] One of hallmarks of this disease is shuffling gait, where the individual leans forward while walking and increases his speed progressively, which results in a fall or contact with a wall. Parkinson's patients also have difficulty in changing direction when walking. The principle of increased dopamine in music therapy would therefore ease parkinsonian symptoms.[15] These effects were observed in Ghai's study of various auditory feedback cues wherein patients with Parkinson's disease experience increased walking speed, stride length as well as decreased cadence.[12]

Huntington's disease

Huntington's disease affects a person's movement, cognitive as well as psychiatric functions which severely affects his or her quality of life.[18] Most commonly, patients with Huntington's Disease most commonly experience chorea, lack of impulse control, social withdrawal and apathy. Schwarz et al. conducted a review over the published literature concerning the effects of music and dance therapy to patients with Huntington's disease. The fact that music is able to enhance cognitive and motor abilities for activities other than those of music related ones suggests that music may be beneficial to patients with this disease.[13] Although studies concerning the effects of music on physiologic functions are essentially inconclusive, studies find that music therapy enhances patient participation and long term engagement in therapy[13] which are important in achieving the maximum potential of a patient's abilities.

Dementia

Individuals with Alzeihmer's disease caused by dementia almost always become animated immediately when hearing a familiar song.[14] Särkämo et al. discusses the effects of music found through a systemic literature review in those with this disease. Experimental studies on music and dementia find that although higher level auditory functions such as melodic contour perception and auditory analysis are diminished in individuals, they retain their basic auditory awareness involving pitch, timbre and rhythm.[14] Interestingly, music-induced emotions and memories were also found to be preserved even in patients suffering from severe dementia. Studies demonstrate beneficial effects of music on agitation, anxiety and social behaviors and interactions.[14] Cognitive tasks are affected by music as well, such as episodic memory and verbal fluency.[14] Experimental studies on singing for individuals in this population enhanced memory storage, verbal working memory, remote episodic memory and executive functions.[14]

References

- ^ a b Ghazanfar, A. A.; Nicolelis, M. A. (2001). "Feature Article: The Structure and Function of Dynamic Cortical and Thalamic Receptive Fields". Cerebral Cortex. 11 (3): 183–193. doi:10.1093/cercor/11.3.183. PMID 11230091.

- ^ a b c Theunissen, F; David, SV; Singh, NC; Hsu, A; Vinje, WE; Gallant, JL (2001). "Estimating spatio-temporal receptive fields of auditory and visual neurons from their responses to natural stimuli". Network: Computation in Neural Systems. 12 (3): 289–316. doi:10.1080/net.12.3.289.316. PMID 11563531. S2CID 199667772.

- ^ a b Baird, A.; Samson, S. V. (2009). "Memory for Music in Alzheimer's Disease: Unforgettable?". Neuropsychology Review. 19 (1): 85–101. doi:10.1007/s11065-009-9085-2. PMID 19214750. S2CID 14341862.

- ^ Bailey, D.L; Townsend, D.W.; Valk, P.E.; Maisey, M.N. (2003). Positron Emission Tomography: Basic Sciences. Secaucus, NJ: Springer-Verlag. Springer. ISBN 978-1852337988.

- ^ a b c d Hauk, O; Wakeman, D; Henson, R (2011). "Comparison of noise-normalized minimum norm estimates for MEG analysis using multiple resolution metrics". NeuroImage. 54 (3): 1966–74. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.053. PMC 3018574. PMID 20884360.

- ^ Fitzgerald, P; Fountain, S; Daskalakis, Z (2006). "A comprehensive review of the effects of rTMS on motor cortical excitability and inhibition". Clinical Neurophysiology. 117 (12): 2584–2596. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2006.06.712. PMID 16890483. S2CID 31458874.

- ^ Brown, S.; Martinez, M. J.; Parsons, L. M. (2006). "Music and language side by side in the brain: A PET study of the generation of melodies and sentences". European Journal of Neuroscience. 23 (10): 2791–2803. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.530.5981. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04785.x. PMID 16817882. S2CID 15189129.

- ^ Jentschke, S.; Koelsch, S.; Sallat, S.; Friederici, A. D. (2008). "Children with Specific Language Impairment Also Show Impairment of Music-syntactic Processing". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 20 (11): 1940–1951. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.144.5724. doi:10.1162/jocn.2008.20135. PMID 18416683. S2CID 6678801.

- ^ Stewart, L.; Walsh, V.; Frith, U. T. A.; Rothwell, J. (2001). "Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Produces Speech Arrest but Not Song Arrest". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 930 (1): 433–435. Bibcode:2001NYASA.930..433S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.671.9203. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05762.x. PMID 11458860. S2CID 31971115.

- ^ Granier-Deferre, C; Ribeiro, A; Jacquet, A; Bassereau, S (2011). "Near-term fetuses process temporal features of speech". Developmental Science. 14 (2): 336–352. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.00978.x. PMID 22213904.

- ^ Gross, W; Linden, U; Ostermann, T (2010). "Effects of music therapy in the treatment of children with delayed speech development -results of a pilot study". BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 10 (1): 39. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-10-39. PMC 2921108. PMID 20663139.

- ^ a b Ghai, S; Ghai, I (2018). "Effect of rhythmic auditory cueing on parkinsonian gait: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 508. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8..506G. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-16232-5. PMC 5764963. PMID 29323122.

- ^ a b c Schwarz, AE; van Walsen, MR (2019). "Therapeutic Use of Music, Dance and Rhythmic Auditory Cueing for Patients with Huntington's Disease: A Systematic Review". Journal of Huntington's Disease. 8 (4): 393–420. doi:10.3233/JHD-190370. PMC 6839482. PMID 31450508.

- ^ a b c d e f Särkämo, T; Sihbonen, AJ (2018). "Golden oldies and silver brains: Deficits, preservation, learning and rehabilitation effects of music in ageing-related neurological disorders". Cortex. 109: 104–123. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2018.08.034. hdl:10138/311678. PMID 30312779. S2CID 52971959.

- ^ a b c Stegemöller, Elizabeth (2014). "Exploring a Neuroplasticity Model of Music Therapy". Journal of Music Therapy. 51 (3): 211–217. doi:10.1093/jmt/thu023. PMID 25316915 – via Oxford Academic.

- ^ Weinstein, CJ; Kay, DB (2015). "Translating the science into practice". Sensorimotor Rehabilitation - at the Crossroads of Basic and Clinical Sciences. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 218. pp. 331–360. doi:10.1016/bs.pbr.2015.01.004. ISBN 9780444635655. PMID 25890145 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Tiarhou, Lazaros (2013). "Dopamine and Parkinson's Disease". Madame Curie Bioscience Database – via NCBI.

- ^ Mayo Clinic Staff (May 16, 2018). "Huntington's disease". Mayo Clinic.