Talk:Pomerania in the High Middle Ages

| This article is rated C-class on Wikipedia's content assessment scale. It is of interest to the following WikiProjects: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Foundation of towns

Hi. Tinynanorobots, Volunteer Marek, you guys just can't be serious about removing such an extensive section of the article without even having a consent on the talk page or even giving proper reasons to do this. Either you outsource this to a separate article, or to another article. And you'll have to explain why you think this should be taken out. That's how the Wiki project works fellows. -- Horst-schlaemma (talk) 11:47, 5 April 2014 (UTC)

Extracted:

Extended content |

|---|

Foundation of townsBefore the Ostsiedlung, urban settlements of the emporia[clarification needed] and gard[nb 1] types existed for example the city of Szczecin (Stettin) which counted between 5,000 to 9,000 inhabitants,[1][2] and other locations like Demmin, Wolgast, Usedom, Wollin/Wolin, Kolberg/Kołobrzeg, Pyritz/Pyrzyce and Stargard, though many of the coastal ones declined during the 12th century warfare.[3] Previous theories that urban development was "in its entirety" brought to areas such as Pomerania, Mecklenburg or Poland by Germans are now discarded, and studies show that these areas had already growing urban centres in process similar to Western Europe[4] These population centres were usually centered around a gard, which was a fortified castle which housed the castellan as well as his staff and the ducal craftsmen. The surrounding town consisted of suburbs, inhabited by merchants, clergy and the higher nobles. According to Piskorski this portion usually included "markets, taverns, butcher shops, mints, which also exchanged coins, toll stations, abbeys, churches and the houses of nobles".[5] Important changes connected to Ostsiedlung included

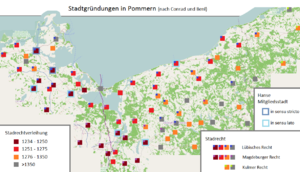

Medieval Greifswald with the checkerboard-type layout typical for Ostsiedlung towns.[15] Locators set up rectangular blocs in an area resembling an oval with a central market, and organized the settlement. "Foundation"[clarification needed] of towns in the area of the later Pomeranian province, superimposed on OSM. Most towns with Lübeck law appealed to Greifswald, most towns with Magdeburg law to Stettin.[16] Between 1234 and 1299, 34 towns[15] were founded[17] in the Pomeranian duchy, this number increased to 58 in the late Middle Ages.[15] The towns were built on behalf of the Pomeranian dukes or ecclesiastic bodies like monasteries and orders.[18] Most prominent on this issue was Barnim I of Pomerania-Stettin, who since was entitled "the towns' founder". The towns build on his behalf were granted Magdeburg Law and settled predominantly by people from the western Margraviate of Brandenburg, while the towns founded in the North (most on behalf of the Rugian princes and Wartislaw III of Pomerania-Demmin were granted Lübeck Law and were settled predominantly by people from Lower Saxony. The first towns were Stralsund (Principality of Rügen, 1234), Prenzlau (Uckermark, then Pomerania-Stettin, 1234), Bahn (Knights Templar, about 1234), and Stettin (1237/43), Gartz (Oder) (Pomerania-Stettin, 1240), and Loitz (by Detlev of Gadebusch, 1242). Other towns built in the 1240s were Demmin, Greifswald (by Eldena Abbey), Altentreptow.[19] According to Rădvan (2010), "a relevant example for how towns were founded (civitas libera) is Prenzlau today within German boundaries, close to Poland. It was here that, a short distance from an older Slavic settlement, duke Barnim I of Pomerania entrusted in 1234-35 the creation of a new settlement to eight contractors (referred to as fondatores) originating from Stendal, Saxony. The eight, who were probably relatives to some degree, were granted 300 Hufen (around 4800 ha) that were to be distributed to settlers, each one of the fondatores being entitled to 160 ha for himself and the right to build mills; one of them became the duke's representative. The settlers' land grant was tax exempt for three years, and it was to be kept in eternal and hereditary possession. A 1.5 km (1 mi) perimeter around the settlement was provided for unrestricted use by the community of pastures, forests, or fishing. Those trading were dispensed of paying taxes for land under ducal authority. Without being mentioned in the founding act, the old Slavic community persisted as nothing more that a suburb to the new town. Aside from several topical variations, many settlements in medieval Poland and other areas followed a similar pattern."[20] Many towns with a gard in close proximity had the duke level the castle when they grew in power. Stettin, where the castle was inside the town, had the duke level it already in 1249,[21] other towns were to follow. The fortified new towns had succeeded the gards as strongholds for the country's defense. In many cases, the former Slavic settlement would become a suburb of the German town ("Wiek", "Wieck"). In Stettin, two "Wiek" suburbs were set up anew outside the walls, to which most Slavs from within the walls were resettled. Such Wiek settlements did initially not belong to the town, but to the duke, although they were likely to come into possession of the town in the course of the 14th century. Also in the 14th century, Slavic Wiek suburbs lost their Slavic character.[22] In western Pomerania, including Rugia, the process of Ostsiedlung differed from how it took place in other parts of Eastern Europe in that a high proportion of the settlers was composed of Scandinavians, especially Danes, and migrants from Scania. The highest Danish influence was on the Ostsiedlung of the then Danish Rugian principality. In the possessions of the Rugian Eldena Abbey, a Danish establishment, settlers who opened a tavern would respectively be treated according to Danish, German and Wendish law.[23] Wampen, Ladebow, and other villages near Greifswald are of Danish origin.[24] Yet, many Scandinavian settlers in the Pomeranian towns were of German origin, moving from older German merchants' settlements in Sweden to the newly founded towns at the Southern Baltic shore.[25] Refs

|

HS, yes, this section is way too extensive and way too long (not to mention that it has some POV problems). Most of it, if not all, *already* is "outsourced" to another article, Ostsiedlung where it belongs. This is a general level article.

BTW, the talk page isn't the place to fork content. I've collapsed rather than deleted the text but it really shouldn't be here.Volunteer Marek (talk) 12:12, 5 April 2014 (UTC)

- There's NO consensus to do this. Stop the edit-warring and reverting. We need more input/opinions here if something like this is to be done. I say keep it. -- Horst-schlaemma (talk) 15:32, 6 April 2014 (UTC)

- More opinions? How do you propose I gain more opinions? I discussed it with everyone who would discuss it, and gave other's quite some time to discuss it. I am still willing to discuss it. However, people only seem to want to discuss changes after they happen. Please, give you opinions on why any part of it should stay in this article. Tinynanorobots (talk) 18:58, 22 April 2014 (UTC)

Cite error: There are <ref group=nb> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=nb}} template (see the help page).