Syncretism

Syncretism (/ˈsɪŋkrətɪzəm, ˈsɪn-/)[1] is the practice of combining different beliefs and various schools of thought. Syncretism involves the merging or assimilation of several originally discrete traditions, especially in the theology and mythology of religion, thus asserting an underlying unity and allowing for an inclusive approach to other faiths. While syncretism in art and culture is sometimes likened to eclecticism, in the realm of religion, it specifically denotes a more integrated merging of beliefs into a unified system, distinct from eclecticism, which implies a selective adoption of elements from different traditions without necessarily blending them into a new, cohesive belief system. Syncretism also manifests in politics, known as syncretic politics.

The English word is first attested in the early 17th century [2]. It is from Modern Latin syncretismus, drawing on the συγκρητισμός (synkretismos), supposedly meaning "Cretan federation." However, this is a spurious etymology derived from the naive idea in Plutarch's 1st-century AD essay on "Fraternal Love (Peri Philadelphias)" in his collection Moralia. He cites the example of the Cretans, who compromised and reconciled their differences and came together in alliance when faced with external dangers. "And that is their so-called Syncretism [Union of Cretans]." A more likely etymology is from sun- ("with") plus kerannumi ("mix") and its related noun, krasis ("mixture").

Social and political roles

Overt syncretism in folk belief may show cultural acceptance of an alien or previous tradition, but the "other" cult may survive or infiltrate without authorized syncresis. For example, some conversos developed a sort of cult for martyr-victims of the Spanish Inquisition, thus incorporating elements of Catholicism while resisting it.

The Kushite kings who ruled Upper Egypt for approximately a century and the whole of Egypt for approximately 57 years, from 721 to 664 BCE, constituting the Twenty-fifth Dynasty in Manetho's Aegyptiaca, developed a syncretic worship identifying their own god Dedun with the Egyptian Osiris. They maintained that worship even after they had been driven out of Egypt. A temple dedicated to this syncretic god, built by the Kushite ruler Atlanersa, was unearthed at Jebel Barkal.[3][4]

Syncretism was common during the Hellenistic period, with rulers regularly identifying local deities in various parts of their domains with the relevant god or goddess of the Greek Pantheon as a means of increasing the cohesion of their kingdom. This practice was accepted in most locations but vehemently rejected by the Jews, who considered the identification of Yahweh with the Greek Zeus as the worst of blasphemy.

The Roman Empire continued the practice, first by the identification of traditional Roman deities with Greek ones, producing a single Greco-Roman pantheon, and then identifying members of that pantheon with the local deities of various Roman provinces.

Some religious movements have embraced overt syncretism, such as the case of melding Shintō beliefs into Buddhism or the amalgamation of Germanic and Celtic pagan views into Christianity during its spread into Gaul, Ireland, Britain, Germany and Scandinavia. In later times, Christian missionaries in North America identified Manitou, the spiritual and fundamental life force in the traditional beliefs of the Algonquian groups, with the God of Christianity. Similar identifications were made by missionaries at other locations in the Americas and Africa who encountered a local belief in a Supreme God or Supreme Spirit of some kind.

Indian influences are seen in the practice of Shi'i Islam in Trinidad. Others have strongly rejected it as devaluing and compromising precious and genuine distinctions; examples include post-Exile Second Temple Judaism, Islam, and most of Protestant Christianity.[further explanation needed][citation needed]

Syncretism tends to facilitate coexistence and unity between otherwise different cultures and world views (intercultural competence), a factor that has recommended it to rulers of multiethnic realms. Conversely, the rejection of syncretism, usually in the name of "piety" and "orthodoxy", may help to generate, bolster or authenticate a sense of uncompromised cultural unity in a well-defined minority or majority.

All major religious conversions of populations have had elements from prior religious traditions incorporated into legends or doctrine that endure with the newly converted laity.[5]

Religious syncretism

Religious syncretism is the blending of two or more religious belief systems into a new system, or the incorporation into a religious tradition of beliefs from unrelated traditions. This can occur for many reasons, and the latter scenario happens quite commonly in areas where multiple religious traditions exist in proximity and function actively in a culture, or when a culture is conquered, and the conquerors bring their religious beliefs with them, but do not succeed in entirely eradicating the old beliefs or (especially) practices.

Religions may have syncretic elements to their beliefs or history, but adherents of so-labeled systems often frown on applying the label, especially adherents who belong to "revealed" religious systems, such as the Abrahamic religions, or any system that exhibits an exclusivist approach. Such adherents sometimes see syncretism as a betrayal of their pure truth. By this reasoning, adding an incompatible belief corrupts the original religion, rendering it no longer true. Indeed, critics of a syncretistic trend may use the word or its variants as a disparaging epithet, as a charge implying that those who seek to incorporate a new view, belief, or practice into a religious system pervert the original faith. Non-exclusivist systems of belief, on the other hand, may feel quite free to incorporate other traditions into their own. Keith Ferdinando notes that the term "syncretism" is an elusive one,[6] and can refer to substitution or modification of the central elements of a religion by beliefs or practices introduced from elsewhere. The consequence under such a definition, according to Ferdinando, can lead to a fatal "compromise" of the original religion's "integrity".[7]

In modern secular society, religious innovators sometimes construct new faiths or key tenets syncretically, with the added benefit or aim of reducing inter-religious discord. Such chapters often have a side-effect of arousing jealousy and suspicion among authorities and ardent adherents of the pre-existing religion. Such religions tend to inherently appeal to an inclusive, diverse audience. Sometimes the state itself sponsored such new movements, such as the Living Church founded in Soviet Russia and the German Evangelical Church in Nazi Germany, chiefly to stem all outside influences.

Cultures and societies

According to some authors, "Syncretism is often used to describe the product of the large-scale imposition of one alien culture, religion, or body of practices over another that is already present."[8] Others such as Jerry H. Bentley, however, have argued that syncretism has also helped to create cultural compromise. It provides an opportunity to bring beliefs, values, and customs from one cultural tradition into contact with, and to engage different cultural traditions. Such a migration of ideas is generally successful only when there is a resonance between both traditions. While, as Bentley has argued, there are numerous cases where expansive traditions have won popular support in foreign lands, this is not always so.[9]

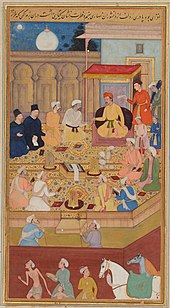

Din-i Ilahi

In the 16th century, the Mughal emperor Akbar proposed a new religion called the Din-i Ilahi ("Divine Faith"). Sources disagree with respect to whether it was one of many Sufi orders or merged some of the elements of the various religions of his empire.[10][11] Din-i Ilahi drew elements primarily from Islam and Hinduism but also from Christianity, Jainism, and Zoroastrianism. More resembling a personality cult than a religion, it had no sacred scriptures, no priestly hierarchy, and fewer than 20 disciples, all hand-picked by Akbar himself. It is also accepted that the policy of sulh-i-kul, which formed the essence of the Dīn-i Ilāhī, was adopted by Akbar as a part of general imperial administrative policy. Sulh-i-kul means "universal peace".[12][13]

Enlightenment

The syncretic deism of Matthew Tindal undermined Christianity's claim to uniqueness.[14] The modern, rational, non-pejorative connotations of syncretism arguably date from Denis Diderot's Encyclopédie articles Eclecticisme and Syncrétistes, Hénotiques, ou Conciliateurs. Diderot portrayed syncretism as the concordance of eclectic sources. Scientific or legalistic approaches of subjecting all claims to critical thinking prompted at this time much literature in Europe and the Americas studying non-European religions such as Edward Moor's The Hindu Pantheon of 1810, much of which was almost evangelistically appreciative by embracing spirituality and creating the space and tolerance in particular disestablishment of religion (or its stronger form, official secularisation as in France) whereby believers of spiritualism, agnosticism, atheists and in many cases more innovative or pre-Abrahimic based religions could promote and spread their belief system, whether in the family or beyond.[citation needed]

See also

- Confederacy

- Conflation

- Cultural appropriation

- Cultural assimilation

- Multiculturalism

- Multiple religious belonging

- New religious movement

- Religious pluralism

Notes

- ^ "syncretism". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ The Oxford English Dictionary first attests the word syncretism in English in 1618.

- ^ Kendall, Timothy; Ahmed Mohamed, El-Hassan (2016). "A Visitor's Guide to The Jebel Barkal Temples" (PDF). The NCAM Jebel Barkal Mission. Khartoum: Sudan. Nubian Archeological Development Organization (Qatar-Sudan): 34 & 94.

- ^ Török, László (2002). The Image of the Ordered World in Ancient Nubian Art: The Construction of the Kushite Mind, 800 BC–300 AD. Probleme der Ägyptologie. Vol. 18. Leiden: Brill. p. 158. ISBN 9789004123069.

- ^ Olupona, Jacob K. (2014). African Religions: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-19-979058-6. OCLC 839396781.

- ^ Ferdinando, K. (1995). "Sickness and Syncretism in the African Context" (PDF). In Antony Billington; Tony Lane; Max Turner (eds.). Mission and Meaning: Essays Presented to Peter Cotterell. Paternoster Press. ISBN 978-0853646761.

- ^

Ferdinando, Keith (1995). "Sickness and Syncretism in the African Context". In Billington, Antony; Turner, Max (eds.). Mission and Meaning: Essays Presented to Peter Cotterell (PDF). Paternoster Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0853646761. Retrieved 2018-06-30.

The Christian faith is inevitably assimilated in terms of the existing structures of thought of its adherents, whatever their culture. Nevertheless, there are points at which the worldview of any people will be found to be incompatible with central elements of the gospel; if conversion to Christianity is to be more than purely nominal, it will necessarily entail the substantial modification of the traditional worldview at such points. Where this does not occur it is the Christian faith which is modified and thus relativised by the worldview, and the consequence is syncretism. [...] The term 'syncretism' [...] is employed here of the substitution or modification of central elements of Christianity by beliefs of practices introduced from elsewhere. The consequence of such a process is fatally to compromise its integrity.

- ^ Peter J. Claus and Margaret A. Mills, South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia: (Garland Publishing, Inc., 2003).

- ^ Jerry Bentley, Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), viii.

- ^ "Dīn-i Ilāhī | Indian religion". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-02-25.

- ^ Roychoudhury, Makhanlal (1941). The Din-i-Ilahi, or, The Religion of Akbar. University of Calcutta. p. 306. OCLC 3312929.

Din-i-Ilahi ... was not a new religion; it was a Sufi order ... in which all the principles enunciated are to be found in the Quran and in the practices in the contemporary Sufi orders.

- ^ "Why putting less Mughal history in school textbooks may be a good idea". 7 March 2016. [verification needed]

- ^ "Finding Tolerance in Akbar, the Philosopher-King". 10 April 2013. [verification needed]

- ^ Harding, A.J. (1995). The Reception of Myth in English Romanticism. Tall Buildings and Urban Environment. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1007-4. Retrieved 2023-02-11.

Further reading

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Assmann, Jan (1997). Moses the Egyptian: The Memory of Egypt in Western Monotheism. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-58738-0.

- Assmann, Jan (2008). "Translating Gods: Religion as a Factor of Cultural (Un)Translatability". In de Vries, Hent (ed.). Religion: Beyond a Concept. Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0823227242.

- HadžiMuhamedović, Safet (2018) Waiting for Elijah: Time and Encounter in a Bosnian Landscape. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- HadžiMuhamedović, Safet (2018) "Syncretic Debris: From Shared Bosnian Saints to the ICTY Courtroom". In: A. Wand (ed.) Tradition, Performance and Identity Politics in European Festivals (special issue of Ethnoscripts 20:1).

- Cotter, John (1990). The New Age and Syncretism, in the World and in the Church. Long Prairie, Minn.: Neumann Press. 38 p. N.B.: The approach to the issue is from a conservative Roman Catholic position. ISBN 0-911845-20-8

- Pakkanen, Petra (1996). Interpreting Early Hellenistic Religion: A Study Based on the Mystery Cult of Demeter and the Cult of Isis. Foundation of the Finnish Institute at Athens. ISBN 978-951-95295-4-7.

- Smith, Mark S. (2010) [2008]. God in Translation: Deities in Cross-Cultural Discourse in the Biblical World. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6433-8.

External links

Media related to Syncretism at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Syncretism at Wikimedia Commons