Suppression of Mokotów

The Suppression of Mokotów was a wave of mass murders, looting, arson and rapes that swept through the Warsaw district of Mokotów during the Warsaw Uprising in 1944. Crimes against prisoners of war and civilians of the district were committed by the Germans until the capitulation of Mokotów on September 27, 1944, although they intensified in the first days of the uprising.

German crimes on the first day of the uprising

On August 1, 1944, at 5 p.m., Home Army soldiers hit German facilities in all districts of occupied Warsaw. On that day the units of the 5th Home Army District "Mokotów" suffered heavy losses during unsuccessful attacks on the heavily strengthened German resistance points on Rakowiecka and Puławska Streets. The insurgents also failed to gain many other targets - such as barracks in schools on Kazimierzowska and Woronicza Streets, Fort Mokotów, or horse racing track in Służewiec.[1] As a result of this defeat, a significant part of the units of the 5th District withdrew to the Kabaty Forest. On the other hand, five companies of the "Baszta" regiment under the command of Colonel Stanisław Kamiński "Daniel" manned residential flats in a square formed by streets: Odyńca - Goszczyński - Puławska - Niepodległości.[2] However, in the following days the insurgents managed to expand their possessions and organize a strong resistance centre in Upper Mokotów.

On the night of August 1–2, 1944, SS, police and Wehrmacht units committed a number of war crimes in Mokotów. Insurgents taken captive were shot, wounded were killed. The Germans disregarded the fact that the Home Army soldiers conducted the fight openly and had the legal markings of a soldier, i.e. they fought in accordance with the Hague Convention.[3] All Polish soldiers captured during the attack on German resistance points on Rakowiecka Street were murdered,[1] as well as several dozen prisoners from the Home Army "Karpaty" battalion, which attacked the horse racing track in Służewiec.[4][5] The Germans also shot at least 19 wounded and captured insurgents from the Home Army "Olza" battalion, which was crushed during the attack on Fort Mokotów. Some of the victims were buried alive, which was confirmed by the results of the exhumation carried out in 1945.[6][7]

The first massacre of civilians from Mokotów also took place that night. After the repulse of the Polish attack, the Luftwaffe soldiers belonging to the Fliegerhorst-Kommandantur Warschau-Okecie personnel (English: "Command of the Okęcie Military Airfield") gathered nearly 500 civilians on the territory of Fort Mokotów. The displacements were accompanied by immediate executions. Many inhabitants of Bachmacka, Baboszewska and Syrynska Streets were murdered at that time. In the house at 97 Racławicka Street, the Germans gathered almost fourteen residents in a cellar and then murdered them with grenades.[8][9] The murders of prisoners and civilians were ordered by the commander of the Okęcie garrison, General Doerfler.[8]

Hitler's order on the destruction of Warsaw and its execution in Mokotów

In the wake of the outbreak of the uprising, Hitler gave an oral order to Reichsführer-SS Himmler and the Chief of Staff of the Supreme Command of the Land Forces (OKH), General Heinz Guderian, to level Warsaw with the ground and murder all its inhabitants.[10] According to the SS-Obergruppenführer Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski, who was appointed commander of the forces appointed to suppress the uprising, the order was more or less as follows: "Every inhabitant should be killed, no prisoners should be taken. Warsaw is to be razed to the ground and in this way a terrifying example is to be created for the whole of Europe".[11] Hitler's order to destroy Warsaw was also given to the commanders of the German garrison in Warsaw. SS-Oberführer Paul Otto Geibel, commander of the SS and the police (SS- und Polizeiführer) for the Warsaw district, testified after the war that on the evening of August 1, Himmler ordered him by phone: "You should destroy tens of thousands".[12] On August 2, the commander of the Warsaw garrison, General Reiner Stahel, ordered the Wehrmacht units subordinate to him to murder all men considered to be actual or potential insurgents and to take hostages from the civilian population (including women and children).[13]

Mokotów was manned by strong German units at that time - among others, the 3rd reserve SS armoured grenadier battalion in the barracks at Rakowiecka Street (SS-Stauferkaserne), anti-aircraft artillery batteries in the Mokotów Field, Luftwaffe infantry units in the Mokotów Fort and anti-aircraft artillery barracks in Puławska Street (Flakkaserne), and a gendarmerie unit in the district command building in Dworkowa Street. Despite this, the execution of Hitler's extermination order did not bring such tragic results in Mokotów as in Wola, Ochota or in the Southern Downtown (Śródmieście Południowe). The district was considered to be a peripheral section, so for a long time Germans did not carry out major offensive activities there. However, the German troops, passively behaving towards the insurgents, massacred the Polish civilians who were within their reach.[14] House burnings, looting and rape of women were also carried out.[15][16] The survivors were expelled from their homes and sent to the transit camp in Pruszków, from where many people were later deported to concentration camps or sent to forced labour in the Third Reich.

Massacre in the Mokotów prison

When the uprising broke out, there were 794 prisoners in the Mokotów prison at Rakowiecka Street 37, including 41 minors.[17] On August 1, the building was attacked by Home Army soldiers who managed to enter the prison and occupy the administrative building, but were unable to reach the penitentiary buildings.[18]

On August 2, the court inspector Kirchner, who was the head of the prison, was summoned to the nearby SS barracks at 4 Rakowiecka Street, SS-Obersturmführer Martin Patz, the commander of the 3rd SS reserve battalion of armoured grenadiers, told him that General Reiner Stahel had ordered the execution of all the prisoners. This decision was also approved by SS-Oberführer Geibel, who additionally ordered the execution of Polish guards. Kirchner then drew up a takeover report, on the basis of which he placed at Patz's disposal all the prisoners in the prison.[19] The same day, in the afternoon, an SS unit entered the prison. Nearly 60 prisoners were forced to dig three mass graves in the prison yard, after which they were shot with machine guns. Then the Germans started taking the remaining prisoners out of their cells and murdering them over the dug graves. Over 600 people imprisoned in Mokotów prison died during the several hours of execution.[17][20]

The slaughter that took place in the prison courtyard was perfectly visible from the windows of the cells, and the prisoners who watched it realized that they were sentenced to death and that they had nothing to lose. The prisoners from units 6 and 7 on the second floor decided to take a desperate step and attacked the perpetrators. Later, under cover of night and with the help of the population of the surrounding houses, from 200[17] to 300[21] prisoners managed to get to the area controlled by the insurgents.

Massacre in the Jesuit monastery at Rakowiecka Street

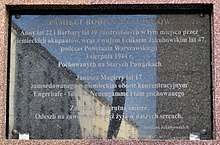

On the first day of the uprising, the House of Writers of the Society of Jesus at 61 Rakowiecka Street was not included in the fighting. A dozen or so civilians hid in the monastery as the shooting prevented them from returning home. In the morning of August 2, the House of Writers was bombarded by German anti-aircraft guns from the nearby Mokotow Field, and soon afterwards it was invaded by an SS unit of about 20 people, most probably sent from the nearby Stauferkaserne. The SS officers accused the people staying in the monastery of shooting German soldiers from the building. After a brief search, which did not lead to finding any evidence to support these accusations, the Germans led Father Edward Kosibowicz, the Superior of the monastery, out of the building, allegedly to provide additional explanations to the command. In fact, he was murdered with a shot to the back of his head in the Mokotow Field.[22][23]

After some time, other Poles were crowded in a small room located in the basement of the monastery, after which couple of grenades were thrown in. The methodical killing of the injured lasted for many hours. More than 40 people fell victims to the massacre, including 8 priests and 8 brothers of the Society of Jesus. The bodies of the murdered were covered with gasoline and set on fire.[Comments 1] Fourteen people (mostly injured) survived as they managed to get out of the pile of bodies and escape from the monastery after the Germans left for a moment.[22][23]

Murdering the civilian population

In the first days of August, German troops in Mokotów - both SS and police units, as well as the Wehrmacht - repeatedly made trips to terrorize the Polish civilian population. These actions were usually accompanied by ad-hoc executions combined with the burning of houses. On August 2, SS soldiers from the barracks on Rakowiecka Street went to Madalińskiego Street, where they started murdering civilians. At that time, at least several dozen residents of houses no. 18, 20, 19/21, 22, 23 and 25 (mostly men) were shot dead.[24][25] Six residents of the house at 76 Kazimierzowska Street were also murdered (three women and a baby).[25][26] In the house at 27 Madalińskiego Street, the Germans locked ten men in a small carpentry workshop, where they were burned alive.[24][25]

On August 3, SS-Oberführer Geibel, having reinforced the Gendarmerie unit of the district command at Dworkowa Street with several tanks, ordered a murder of civilians to be carried out in the area of Puławska Street.[27] The gendarmes commanded by Oberleutnant Karl Lipscher made a trip, moving along Puławska Street in a southern direction. On Szustra Street (present Jarosław Dąbrowskiego) they shot about 40 residents of houses no. 1 and 3.[28] Then they reached Boryszewska Street, shooting at the escaping civilians, whose bodies covered Pulawska Street and it's crossroads. On that day, most of the residents of the houses located in the area of Puławska - Belgijska - Boryszewska - Wygoda streets were murdered.[27][29][30] At least 108 residents of houses at 69, 71 and 73/75 Puławska Street and several dozen residents of houses at Belgijska Street died at that time. Many women and children were murdered.[31] On the other hand, the Germans and their Ukrainian collaborators took over 150 people out of their homes at 49 and 51 Puławska Street, most of them women and children. The detainees were arranged in triples and led to the headquarters of the gendarmerie at Dworkowa Street. When the column reached the edge of the slope, the stairs leading towards Belwederska Street (now Morskie Oko park), the Germans moved the barbed wire entanglements suggesting that they allowed civilians to cross into the territory controlled by the insurgents. Some of the group had already walked down the steps when the gendarmes unexpectedly opened fire from machine guns. About 80 people died, including many children.[32][33] During the execution, Edward Malicki (a.k.a. Maliszewski), who served as a Volksdeutsch in the gendarmerie, stood out with particular ruthlessness.[34] In addition, German airmen murdered between 10 and 13 people in the house at 25 Bukowińska Street on the same day.[35]

In the morning of August 4, two companies of Regiment "Baszta" made a failed attack on the Gendarmerie headquarters in Dworkowa Street. After the rebels were repulsed, the Germans decided to take revenge on the civilian population.[36] The gendarmes from Dworkowa, supported by a unit of Ukrainian collaborators from the school on Pogodna Street, tightly blocked small Olesińska Street (situated opposite the gendarmerie command). Several hundred residents of houses no. 5 and 7 were put in cellars and murdered with grenades. Those who tried to get out of the cellars, turned into mass graves, were killed with machine guns.[37] Between 100[38] and 200[36] people fell victim to the massacre. It was one of the biggest German crimes committed in Mokotów during the Warsaw Uprising.[37]

The area around Rakowiecka Street was also suppressed on August 4. SS-men from the Stauferkaserne barracks and aviators from the barracks on Puławska Street rushed into the houses, throwing grenades and shooting at the people opening their doors. At that time, about 30 residents of houses at 5, 9 and 15 Rakowiecka Street and at least 20 residents of houses at 19/21 and 23 Sandomierska Street were murdered.[39] Two wounded women were left in a burning tenement house to be burned alive.[40]

A number of crimes against the population of Mokotów were also committed by the Germans on August 5. In the evening, SS men and policemen sent from the seat of Sicherheitspolizei in Szucha Avenue surrounded a quarter of houses closed with Puławska - Skolimowska - Chocimska streets - and the Mokotów marketplace.[41] They then murdered about 100 residents of houses at 3 and 5 Skolimowska Street and about 80 residents of the house at 11 Puławska Street.[42] Among the victims was a large number of hiding insurgents, including Captain Leon Światopełk-Mirski "Leon" - the commander of the Third District in District 5 "Mokotów" of the Home Army. The bodies of those shot were drenched in gasoline and burned.[41] On the same day, German pilots murdered 10 to 15 people hiding in a shelter at 61 Bukowińska Street.[35]

In the following days, the Germans continued to set fire to the houses and evicte the population from the occupied quarters of Mokotów.[43] There were also cases of executions of civilians. On August 11, about 20 residents of the tenement house at 132/136 Niepodległości Avenue (including several women) were murdered.[44] On August 21, about 30 residents of the house at 39/43 Madalińskiego Street were shot, and the next day, 7 residents of the house at 29A Kielecka Street were also shot.[45] There are also accounts saying that at the turn of August and September 1944, in the area of gardens on Rakowiecka Street, the Germans executed nearly 60 civilians, including women, the elderly and children.[46]

Crimes in the Stauferkaserne

From August 2, the Germans had been expelling the Polish population from the quarters of Mokotów they occupied. The huge SS barracks at 4 Rakowiecka Street (the so-called SS-Stauferkaserne)[Comments 2] were then turned into a provisional prison. Most of the prisoners were men, who were taken hostage and subjected to concentration camp rigours.[47] Poles imprisoned in Stauferkaserne were detained in inhumane conditions and treated with great brutality. Prisoners received minimal food rations (for example, the first group of prisoners received food after one entire day). Continuous beating was a common occurrence.[48] The detained men were forced to do exhausting work, which included, amongst others: cleaning latrines with bare hands, dismantling insurgent barricades, cleaning tanks, burial of corpses, earthworks on barracks (e.g. digging connecting ditches), cleaning streets, or moving and loading goods robbed by the Germans onto cars. Many of these works were aimed only at the exhaustion and humiliation of the detainees.[48] The difficult living and working conditions soon led to the complete exhaustion of the prisoners. An epidemic of dysentery broke out among them.[48]

During the uprising, the Germans murdered at least 100 Poles in Stauferkaserne.[49] On August 3, the Germans quickly chose from among the prisoners about 45 men, whom they then led out in groups of 15 and shot outside the barracks.[50] The next day, about 40 men from a house located at the corner of Narbutta and Niepodległości Streets were murdered in the courtyard of the barracks.[47][51] Single executions, usually ordered by SS-Obersturmführer Patz, often took place in the barracks. There is a known case of hanging a prisoner in public.[52] Moreover, some of the men imprisoned in Stauferkaserne were taken away by Gestapo "kennels" in an unknown direction and all their traces disappeared. They were probably murdered in the vicinity of the Sipo headquarters in Szucha Avenue. The women from Mokotów imprisoned in the barracks were rushed in front of the tanks towards the insurgents' barricades.[47][53]

Suppression of Sadyba

Since 19 August, the Sadyba[Comments 3] residential complex has been occupied by Home Army units coming from the Chojnów Forests. Sadyba, while in Polish hands, shielded the insurgents' positions in Lower Mokotów from the south. General Günther Rohr, who commanded German forces in the southern districts of Warsaw, was given a task of conquering the settlement by SS-Obergruppenführer Bach, which was to be the first step on the way to expelling the insurgents from the banks of the Vistula River.[54] From August 29, German troops had been attacking Sadyba. The estate was heavily bombarded by German aviation and shot by heavy artillery. In the end, on September 2, the Rohr troops attacking from several sides managed to completely conquer Sadyba. About 200 defenders died. Only a few Home Army soldiers managed to withdraw to the area controlled by the insurgents.[55]

After capturing Sadyba, the Germans murdered all the insurgents who had been taken captive. The wounded were also killed.[56][57] There have also been a number of crimes against civilians. German soldiers - especially those who belonged to the Luftwaffe infantry formations - threw grenades at cellars where civilians were sheltering and carried out ad hoc executions, the victims of which were not only young men suspected of participating in the uprising, but also women, the elderly and children. The bodies of eight naked women with arms tied with barbed wire were later found in one of the mass graves.[56][58] After the fall of Sadyba, at least 80 residents of Podhale, Klarysewska and Chochołowska Streets were murdered.[59] One of the victims of the massacre was Józef Grudziński, an activist of the people's movement, deputy chairman of the underground Council of National Unity.[58] The testimonies of the witnesses show that German soldiers murdering the inhabitants of Sadyba referred to the orders of the command, which spoke about the elimination of all the inhabitants of Warsaw.[56]

After the final seizure of Sadyba, the Germans gathered several thousand surviving civilians in the Piłsudski Fort, where they were saved from execution by an intervention of a German general.[60] It was probably the SS-Obergruppenführer Bach himself who wrote in his diary that he was riding "along thousands of prisoners and civilians" making "flaming speeches" in which he “guaranteed their lives".[61] However, a number of young men suspected of participating in the uprising were murdered on the fort grounds.[60]

Fall of Mokotów

On September 24, 1944, German troops launched a general assault on Upper Mokotów. After four days of fierce fighting, the district fell.[62] Just like in other districts of Warsaw, German soldiers murdered the wounded and medical staff in the insurgent hospitals they conquered. On August 26, several wounded lying in the insurgent hospital at 17 Czeczota Street and in the bandage point at 19 Czeczota Street[63] were shot or burnt alive. On the same day, in the insurgent hospital at 117/119 Niepodległości Avenue, the Germans shot a nurse Ewa Matuszewska "Mewa", and murdered an unknown number of wounded with grenades.[64] After the capitulation of Mokotów (September 27), SS-Obergruppenführer Bach guaranteed the lives of the insurgents who had been taken captive. Despite this, the Germans murdered an unknown number of severely wounded Poles lying in the cellars of houses on Szustra Street (the section between Bałuckiego and Puławska streets), as well as set fire to the insurgent hospital on Puławska 91 Street, where over 20 people died.[65][66]

The Germans brutally expelled the inhabitants from the captured quarters of Mokotów, plundering and setting houses on fire.[67] More than 70 men suspected of taking part in the uprising were shot on Kazimierzowska Street.[68] After the battle was over, the Germans gathered civilians together with injured insurgents on the horse racing track in Służewiec, and then transported them to the transit camp in Pruszków.[69]

Executions at Dworkowa Street

After a few days of the German assault, it became clear that the collapse of the district was inevitable due to the huge advantage of the enemy. In the evening of September 26, on the order of Lieutenant Colonel Józef Rokicki "Daniel" the commanding officer of Mokotów defense, the units of the 10th Infantry Division of the Home Army began evacuating through the sewers to Śródmieście, which was still in Polish hands.[70]

During the chaotic evacuation some of the insurgents got lost in the sewers and after several hours of heavy march they mistakenly left the sewers in the area occupied by the Germans. The captured insurgents and civilians were led to the nearby command of the gendarmerie at Dworkowa Street. There, the Germans separated civilians and some nurses and liaison officers from the rest, while the Home Army soldiers who had been taken captive were ordered to kneel at the fence on the edge of the nearby slope. When one of the insurgents did not endure the tension and tried to take a weapon from the guard, the policemen from Schutzpolizei shot all the captured Home Army soldiers.[69][71] About 140 prisoners fell victim to the massacre.[72]

Another 98 insurgents, captured after leaving the sewers, were shot at Chocimska Street.[73] Before the execution, the Germans tortured the prisoners, forcing them to kneel with their hands raised and beating them with rifle butts.[74]

Liability of the perpetrators

On August 8, 1944, during the uprising, Home Army soldiers accidentally captured the SS-Untersturmführer Horst Stein, who had been leading the massacre on Olesińska Street four days earlier. Stein was brought before an insurgent field court, which sentenced him to death. The sentence was enforced.[75]

In 1954, the Provincial Court for the capital city of Warsaw sentenced Paul Otton Geibel, a SS-Brigadeführer who held formal command over the SS and police units that committed a number of crimes in Mokotów in the first days of August 1944, to life imprisonment. On October 12, 1966, Geibel committed suicide in the Mokotów prison.[76] Dr Ludwig Hahn - Commander-in-Chief of the SD and the Security Police in Warsaw, head of the defence of the "police district", lived for many years in Hamburg under his real name. He was not brought to court until 1972 and was sentenced to 12 years' imprisonment after a one-year trial. During the revision process, the Hamburg sworn court increased the sentence to life imprisonment (1975). Hahn, however, was released in 1983 and died three years later.[77]

In 1980, the Cologne court found SS-Obersturmführer Martin Patz, commander of the SS' 3rd Spare Armored Grenadier Battalion, guilty of murdering 600 prisoners of the Mokotów prison and sentenced him to 9 years in prison. Karl Misling, who was tried in the same trial, received a 4-year prison sentence.[78]

Comments

References

- ^ a b Adam Borkiewicz: Powstanie warszawskie. Zarys działań natury wojskowej. Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy „Pax”, 1969. p. 70-71

- ^ Adam Borkiewicz: Powstanie warszawskie. Zarys działań natury wojskowej. Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy „Pax”, 1969. p. 82

- ^ Antoni Przygoński: Powstanie warszawskie w sierpniu 1944 r. T. I. Warszawa: PWN, 1980. ISBN 83-01-00293-X. p. 239

- ^ Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 204

- ^ Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 207

- ^ Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 177, 180-181

- ^ Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 132

- ^ a b Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 180-181

- ^ Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 131

- ^ Antoni Przygoński: Powstanie warszawskie w sierpniu 1944 r. T. I. Warszawa: PWN, 1980. ISBN 83-01-00293-X. p. 221

- ^ Antoni Przygoński: Powstanie warszawskie w sierpniu 1944 r. T. I. Warszawa: PWN, 1980. ISBN 83-01-00293-X. p. 223

- ^ Szymon Datner, Kazimierz Leszczyński (red.): Zbrodnie okupanta w czasie powstania warszawskiego w 1944 roku (w dokumentach). Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1962. p. 418

- ^ Antoni Przygoński: Powstanie warszawskie w sierpniu 1944 r. T. I. Warszawa: PWN, 1980. ISBN 83-01-00293-X. p. 241

- ^ Adam Borkiewicz: Powstanie warszawskie. Zarys działań natury wojskowej. Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy „Pax”, 1969. p. 330

- ^ Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 343

- ^ Szymon Datner, Kazimierz Leszczyński (red.): Zbrodnie okupanta w czasie powstania warszawskiego w 1944 roku (w dokumentach). Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1962. p. 113-115

- ^ a b c Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 135

- ^ Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 189

- ^ Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 277

- ^ Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 278

- ^ Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 278-279

- ^ a b Szymon Datner, Kazimierz Leszczyński (red.): Zbrodnie okupanta w czasie powstania warszawskiego w 1944 roku (w dokumentach). Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1962. p. 124-127

- ^ a b Felicjan Paluszkiewicz: Masakra w Klasztorze. Warszawa: wydawnictwo Rhetos, 2003. ISBN 83-917849-1-6. p. 10-12

- ^ a b Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 86-87

- ^ a b c Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 275-276

- ^ Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 134

- ^ a b Antoni Przygoński: Powstanie warszawskie w sierpniu 1944 r. T. I. Warszawa: PWN, 1980. ISBN 83-01-00293-X. p. 250-251

- ^ Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 160

- ^ Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 289-290

- ^ Ludność cywilna w powstaniu warszawskim. T. I. Cz. 2: Pamiętniki, relacje, zeznania. Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1974. p. 115-116

- ^ Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 17, 129-130

- ^ Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 290

- ^ Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 38-39

- ^ Szymon Datner, Kazimierz Leszczyński (red.): Zbrodnie okupanta w czasie powstania warszawskiego w 1944 roku (w dokumentach). Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1962. p. 133-135

- ^ a b Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 22

- ^ a b Adam Borkiewicz: Powstanie warszawskie. Zarys działań natury wojskowej. Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy „Pax”, 1969. p. 118

- ^ a b Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 306-308

- ^ Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 113-114

- ^ Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 133-134

- ^ Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 305-306

- ^ a b Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 321-322

- ^ Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 128

- ^ Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 342-343

- ^ Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 102

- ^ Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 69, 78

- ^ Szymon Datner, Kazimierz Leszczyński (red.): Zbrodnie okupanta w czasie powstania warszawskiego w 1944 roku (w dokumentach). Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1962. p. 114

- ^ a b c Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 276

- ^ a b c Szymon Datner, Kazimierz Leszczyński (red.): Zbrodnie okupanta w czasie powstania warszawskiego w 1944 roku (w dokumentach). Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1962. p. 110-112

- ^ Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 133

- ^ Szymon Datner, Kazimierz Leszczyński (red.): Zbrodnie okupanta w czasie powstania warszawskiego w 1944 roku (w dokumentach). Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1962. p. 116

- ^ Szymon Datner, Kazimierz Leszczyński (red.): Zbrodnie okupanta w czasie powstania warszawskiego w 1944 roku (w dokumentach). Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1962. p. 121

- ^ Szymon Datner, Kazimierz Leszczyński (red.): Zbrodnie okupanta w czasie powstania warszawskiego w 1944 roku (w dokumentach). Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1962. p. 110-112, 117, 123

- ^ Szymon Datner, Kazimierz Leszczyński (red.): Zbrodnie okupanta w czasie powstania warszawskiego w 1944 roku (w dokumentach). Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1962. p. 110, 117

- ^ Adam Borkiewicz: Powstanie warszawskie. Zarys działań natury wojskowej. Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy „Pax”, 1969. p. 345, 347

- ^ Adam Borkiewicz: Powstanie warszawskie. Zarys działań natury wojskowej. Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy „Pax”, 1969. p. 348-352

- ^ a b c Adam Borkiewicz: Powstanie warszawskie. Zarys działań natury wojskowej. Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy „Pax”, 1969. p. 352

- ^ Adam Borkiewicz: Powstanie warszawskie. Zarys działań natury wojskowej. Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy „Pax”, 1969. p. 461

- ^ a b Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 465-466

- ^ Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 27, 70, 122–123.

- ^ a b Ludność cywilna w powstaniu warszawskim. T. I. Cz. 2: Pamiętniki, relacje, zeznania. Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1974. p. 14-15

- ^ Tadeusz Sawicki: Rozkaz zdławić powstanie. Niemcy i ich sojusznicy w walce z powstaniem warszawskim. Warszawa: Bellona, 2010. ISBN 978-83-11-11892-8. p. 82

- ^ Adam Borkiewicz: Powstanie warszawskie. Zarys działań natury wojskowej. Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy „Pax”, 1969. p. 496-501

- ^ Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 29

- ^ Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 574

- ^ Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 130, 161

- ^ Ludność cywilna w powstaniu warszawskim. T. I. Cz. 2: Pamiętniki, relacje, zeznania. Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1974. p. 101-102

- ^ Adam Borkiewicz: Powstanie warszawskie. Zarys działań natury wojskowej. Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy „Pax”, 1969. p. 496

- ^ Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 68

- ^ a b Adam Borkiewicz: Powstanie warszawskie. Zarys działań natury wojskowej. Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy „Pax”, 1969. p. 502

- ^ Adam Borkiewicz: Powstanie warszawskie. Zarys działań natury wojskowej. Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy „Pax”, 1969. p. 497

- ^ Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 595-597

- ^ Marek Getter. Straty ludzkie i materialne w Powstaniu Warszawskim. „Biuletyn IPN”. 8-9 (43-44), sierpień–wrzesień 2004. p. 66

- ^ Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994. p. 28

- ^ Szymon Datner: Zbrodnie Wehrmachtu na jeńcach wojennych w II wojnie światowej. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo MON, 1961. p. 81

- ^ Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. p. 322

- ^ Władysław Bartoszewski: Warszawski pierścień śmierci 1939–1944. Warszawa: Interpress, 1970. p. 424

- ^ Bogusław Kopka: Konzentrationslager Warschau. Historia i następstwa. Warszawa: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2007. ISBN 978-83-60464-46-5. p. 99-100

- ^ Friedo Sachser. Central Europe. Federal Republic of Germany. Nazi Trials. „American Jewish Year Book”. 82, 1982 p. 213

Bibliography

- Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07078-4.

- Władysław Bartoszewski: Warszawski pierścień śmierci 1939–1944. Warszawa: Interpress, 1970.

- Adam Borkiewicz: Powstanie warszawskie. Zarys działań natury wojskowej. Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy „Pax”, 1969.

- Szymon Datner, Kazimierz Leszczyński (red.): Zbrodnie okupanta w czasie powstania warszawskiego w 1944 roku (w dokumentach). Warszawa: wydawnictwo MON, 1962.

- Szymon Datner: Zbrodnie Wehrmachtu na jeńcach wojennych w II wojnie światowej. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo MON, 1961.

- Marek Getter. Straty ludzkie i materialne w Powstaniu Warszawskim. „Biuletyn IPN”. 8-9 (43-44), sierpień–wrzesień 2004.

- Bogusław Kopka: Konzentrationslager Warschau. Historia i następstwa. Warszawa: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2007. ISBN 978-83-60464-46-5.

- Maja Motyl, Stanisław Rutkowski: Powstanie Warszawskie – rejestr miejsc i faktów zbrodni. Warszawa: GKBZpNP-IPN, 1994.

- Felicjan Paluszkiewicz: Masakra w Klasztorze. Warszawa: wydawnictwo Rhetos, 2003. ISBN 83-917849-1-6.

- Antoni Przygoński: Powstanie warszawskie w sierpniu 1944 r. T. I. Warszawa: PWN, 1980. ISBN 83-01-00293-X.

- Friedo Sachser. Central Europe. Federal Republic of Germany. Nazi Trials. „American Jewish Year Book”. 82, 1982 (ang.).

- Tadeusz Sawicki: Rozkaz zdławić powstanie. Niemcy i ich sojusznicy w walce z powstaniem warszawskim. Warszawa: Bellona, 2010. ISBN 978-83-11-11892-8.

- Ludność cywilna w powstaniu warszawskim. T. I. Cz. 2: Pamiętniki, relacje, zeznania. Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1974.