Administrative divisions of Albania

| Administrative divisions of Albania Ndarja Administrative e Republikës së Shqipërisë (Albanian) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Category | Unitary state |

| Location | Albania |

| Number | 12 counties 61 municipalities 373 administrative units 2,972 villages |

| Populations | Total: 2,845,955 |

| Areas | Total: 28,748 km2 (11,100 sq mi) |

| Administrative divisions of Albania |

|---|

|

The administrative divisions of Albania comprise 12 counties, 61 municipalities, 373 administrative units, and 2,972 villages. Since its 1912 Declaration of Independence, Albania has reorganized its domestic administrative divisions 21 times. Its internal boundaries have been enlarged or subdivided into prefectures, counties, districts, subprefectures, municipalities, communes, neighborhoods or wards, villages, and localities.[1][2][3] The most recent changes were made in 2014 and enacted in 2015.

Main administrative divisions

Counties

The first level of government is constituted by the 12 counties (Albanian: qarqe/qarqet), organized into their present form in the year 2000.[3] They are run by a prefect (prefekti) and a county council (këshill/këshilli i qarkut). Prefects are appointed as representatives of the national Council of Ministers.[4]

Municipalities

The second level of government is constituted by the 61 municipalities (bashki/bashkitë). They are run by a mayor (kryebashkiak/kryebashkiaku) and a municipal council (këshill/këshilli bashkiak), elected every 4 years. Before 2015, a bashki was an urban municipality and only covered the jurisdiction of such cities. After 2015, the jurisdiction of the bashki was expanded to cover the nearby rural municipalities.[5][6]

Administrative units

The third level of government is constituted by the 373 administrative units (njësia/njësitë administrative) or units of local administration (njësia/njësite të qeverisjes vendore). Most of these were former rural municipalities or communes (komuna/komunat), which functioned as second-level divisions of the country until 2015. Parts of the administrative units are still further subdivided into Albania's 2,972 villages (fshatra/fshatrat).

History

Ottoman Albania

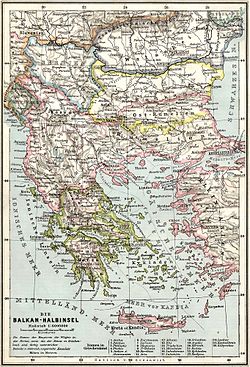

At the beginning of the 20th century, the territory which now forms Albania was divided among the four separate vilayets (Albanian: vilajete/vilajetet) of Scutari, Janina, Manastir, and Kosovo. This helped mix Albanians with the surrounding Greeks, Serbs, and other groups. The four vilayets were divided into the sanjaks (sanxhaqe/sanxhaqet) of Scutari, Durrës, Ioannina, Ergiri, Preveze, Berat, Manastir, Serfiğe, Dibra, Elbasan, Görice, Üsküp, Priştine, İpek, Prizren, and Novi Pazar. The sanjaks were in turn further divided into kazas (kazaja/kazajat) at the town level and nahiyes (nahije/nahijet) at the village level.

Revolutionary Albania

Following the successful War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire in 1912, the first Albanian government led by Ismail Kemal initially retained the former Turkish divisions and offices. This was revised by the "Canon of Albanian Civil Administration" on 22 November 1913, which created a new three tier system. The primary division was into the 8 prefectures (prefektura/prefekturat) of Durrës, Berat, Dibër, Elbasan, Gjirokastër, Korcë, Shkodër, and Vlorë. Each of these was to be overseen by a prefect. The prefectures were divided into subprefectures (nënprefektura/nënprefekturat), which were divided into regions or provinces (krahina/krahinat) for local administration.[7] The authority of this provisional government was never recognized by the Great Powers or the Republic of Central Albania; never administered territory outside Vlorë, Berat, and Lushnjë; and was forced to dissolve after the discovery of its plot to restore some Turkish control to gain more territory and better resist Serbia.

Principality of Albania

Separately, the International Control Commission drafted and enacted the Organic Statute (Statuti Organik)—Albania's first constitution—on 10 April 1914.[8] Primarily functioning as a compromise among the Great Powers of the era, it established the Principality of Albania as a constitutional monarchy to be headed by the German prince Wilhelm Wied and his heirs in primogeniture.[9]

An entire chapter of the Organic Statute was devoted to the administrative division of Albania, explicitly preserving Ottoman names and terms. The primary division was into the 7 sanjaks of Durrës, Berat, Dibër, Elbasan, Gjirokastër, Korçë, and Shkodër.[10] Each would be administered from its namesake city except Dibër.[11] The former Ottoman sanjak of Dibra had been divided among other countries and the city of Debar remained outside the principality's borders.[8] The Albanian sanjak of Dibër, however, expanded a bit with the inclusion of districts of the former sanjak of Prizren.[12] Areas of Chameria that had been in the former sanjak of Ioannina were added to Gjirokastër and the kaza of Leskovik was added to Korçë.[12][13] Each sanjak was overseen by a mutasarrif (mytesarif/mytesarifi) appointed by the central government[14] and a sanjak council (këshill/këshilli i sanxhakut) consisting of five members appointed by law—a secretary, a comptroller, a director of agriculture and trade, a director of public education, and a director of public works—and one member from each of the sanjak's kazas,[15] elected by the local councils and approved by the mutasarrif.[16] The mutasarrif was personally responsible for maintaining public order,[17] controlling the local gendarmerie and police directly.[18] He also controlled local budgets in consultation with the council,[19] providing for public education[20] and inspecting each of the local kazas at least once a year.[21]

The sanjaks were again divided into kaza, each administered by a kaymakam (kajmekam/kajmekami) and his council (këshill/këshilli i kazasë),[22] consisting of three members appointed by law—a secretary, a comptroller, and a director of land taxes—and four members appointed by the local councils and approved by the kaymakam.[23] The kaymakam was responsible for the kaza's finances and public services, including issuing passports,[24] and was required to answer to the sanjak's mutasarrif for a number of issues. The kaza was named and administered from the chief town in its district, headquartered at a city hall (bashki/bashkia).[a] Each municipal council was obliged to hold meetings at the city hall at least once a week.[8]

The kaza were again divided into nahiye, which consisted of a group of villages together representing a population of 4000–7000 people.[25] They were administered by a mudir (mudir/mudiri) and the local council (këshill/këshilli komunal),[26] consisting of the local secretary and 4 members chosen by public election by the mukhtars (muhtarë/muhtarët) of the local villages assembled before the mudir.[27] The mudir was responsible for announcing and enacting the central government's laws, carrying out the census, and collecting taxes;[28] the council was charged with ensuring public hygiene, maintaining local water supplies and roads, and overseeing agricultural development and the use of public lands.[29]

Kingdom of Albania

Under King Zog, Albania reformed its internal administration under the "Municipal Organic Law" of 1921 and the "Civil Code" of February 1928.

The primary division was into 10 prefectures, each led by a prefect. The secondary division was into subprefectures, of which there were 39 in 1927 and 30 by 1934. The subprefects were nominated by the prefects.[30]

The subprefectures were initially divided into 69 provinces, which oversaw local administration through the chiefs of the 2351 villages.[7] In 1928, urban centers were reorganized as municipalities governed by a mayor and municipal council popularly elected every three years and rural areas were organized as 160 communes.[7]

Occupied Albania

Following the Italian occupation of Albania, the country was organized into 10 prefectures, 30 subprefectures, 23 municipalities, 136 communes, and 2551 villages.[7]

Communist Albania

Following the liberation of Albania in World War II, Albania maintained its 10 prefectures and 61 subprefectures but abolished its municipalities and communes. A census was conducted in September 1945, and Law No. 284 (dated 22 August 1946) reformed the internal administration of the country once again. It maintained the 10 prefectures, reduced the number of subprefectures to 39, and organized local government as localities (lokalitete/lokalitetet). In 1947, the subprefectures were replaced by 2 districts (rrathë/rrathët), with local government divided between towns, villages, and localities.[31] In 1953, Law No. 1707 replaced the prefectures with 10 counties divided into 49 districts and 30 localities. In July 1958, the counties were replaced with 26 districts, including a capital district for Tirana. These districts were divided into 203 localities, which oversaw 39 cities and 2655 villages. Larger cities were further divided into neighborhoods or wards (lagje/lagjet). In 1967, the localities were replaced by "unified villages" (fshatra/fshatrat i bashkuar). By 1968, the 26 districts were divided into 65 cities or urban municipalities (divided into 178 neighborhoods) and 437 unified villages or rural municipalities (divided into 2641 villages). This was largely maintained until the late 1980s. In 1990, the 26 districts were divided into 67 cities (divided into 306 neighborhoods) and 539 unified villages (divided into 2848 villages). The capital Tirana was divided into three regions, each of which was further divided into constituent neighborhoods.[7]

See also

- Counties, municipalities, communes, and villages of Albania

- Districts of Albania

- ISO 3166 codes for Albania

- Prefectures of Albania

- Regions of Albania

Notes

- ^ This is the same word as the current municipalities of Albania but at the time referred only to the central office of local government, which provided municipal services and saw the meetings of the municipal council.

References

Citations

- ^ 61 bashkitë do të drejtohen dhe shërbejnë sipas “modelit 1958”

- ^ "HARTA AD MINIST RATIVE TERRITORIALE E BASHKIVE TË SHQIPËRISË" (PDF). Reformaterritoriale.al. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2017-09-09.

- ^ a b "HARTA AD MINIST RATIVE TERRITORIALE E QARQEVE TË SHQIPËRISË" (PDF). Reformaterritoriale.al. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-09-05. Retrieved 2017-09-09.

- ^ "LIGJ Nr. 8927, date 25.7.2002 : Per Prefektin (Ndryshuar me Ligjin Nr. 49/2012 "Për Organizimin dhe Funksionimin e Gjykatave : Administrative dhe Gjykimin r Mosmarrëveshjeve Administrative"" (PDF). Planifikimi.gov.al. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2017-09-09.

- ^ "HARTA ADMINISTRATIVE TERRITORIALE E BASHKIVE TË SHQIPËRISË" (PDF). Ceshtjetvendore.gov.al. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-06. Retrieved 2017-09-09.

- ^ "STAR 2 – Consolidation of the Territorial and Administrative Reform".

- ^ a b c d e "Reforma Territoriale – Historik". Reformaterritoriale.al. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Statuti Organik i Shqipërisë (PDF) (in Albanian).

- ^ "Lo statuto dell'Albania – Prassi Italiana di Diritto Internazionale". www.prassi.cnr.it. Retrieved 2021-12-10.

- ^ Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §95.

- ^ Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §96.

- ^ a b Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §98.

- ^ Clayer 2005, pp. 319, 324, 331.

- ^ Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §100.

- ^ Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §110.

- ^ Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §111.

- ^ Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §106.

- ^ Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §101.

- ^ Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §103.

- ^ Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §108.

- ^ Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §104.

- ^ Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §119.

- ^ Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §125.

- ^ Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §123.

- ^ Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §132.

- ^ Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §133.

- ^ Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §134.

- ^ Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §135.

- ^ Statuti Organik, Ch. VI, §136.

- ^ ""Historia e ndarjes administrative nga Ismail Qemali në '92"". Panorama.com.al. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ "Historia e ndarjes administrative nga Ismail Qemali në '92". Shtetiweb.org. 23 April 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

Bibliography

- Clayer, Nathalie (2005). "The Albanian students of the Mekteb-i Mülkiye: Social networks and trends of thought". In Özdalga, Elisabeth (ed.). Late Ottoman Society: The Intellectual Legacy. Routledge. ISBN 9780415341646.