Strand School

| Strand School | |

|---|---|

| |

| Address | |

Elm Park , England | |

| Information | |

| Type | Grammar School |

| Motto | Advance |

| Religious affiliation(s) | Church of England |

| Established | 1893 |

| Founder | William Braginton |

| Closed | c.1979 |

| Gender | boys |

| Age | 11 to 18 |

| Alumni | Old Strandians |

Strand School was a boys' grammar school in the Tulse Hill area of South London. It moved there in 1913 from its original location at King's College in London's Strand.

Distinguished in its heyday for its contribution of young men to the civil service, it finally closed its doors in 1979 after hotly contested attempts by the education authorities from the early 1950s onwards to turn it into a comprehensive school.

Former pupils included a leader of the Greater London Council, figures prominent in the world of entertainment, and the scientist and environmentalist James Lovelock, originator of the Gaia hypothesis.

History

Origins

Strand School got its name from the fact that it originated in the evening department of King's College in London's Strand. The teaching of evening classes commenced there in 1848; under Alfred Barry, principal between 1868 and 1883, these were "considerably extended":[1]

- When in 1875 the government extended the range of the Civil Service entry examination, William Braginton ... set up private classes in rooms at King's College in the Strand, for those seeking entry into the lower grades. The prestige of being associated with the university college was an added benefit.[1]

The Civil Service Department, as it was known in the early years, started with an intake of 172 men: it did not yet constitute a school for boys. In 1892 Braginton got permission to run a correspondence course, and day classes, for pupils wishing to compete for "boy clerkships" and "boy copyistships". Thus, in 1893, began Strand School.[1][dead link]

The school's name was not apparent, however, till 1897, when King's College School moved to Wimbledon, making it possible for the commercial school to move into the college basement. Examinations on offer had by this time increased beyond those of the civil service as such, to include telegraph learners, assistant surveyorships, as well as those for customs and excise appointments.[2] The success rate of Strand pupils was noteworthy.[2] Many Old Strandians, as they became known, went on to distinguished careers in the civil service.[3] In 1900 the London County Council (LCC) agreed that intermediate county scholarships could be held there, and in 1905 it was allowed to become a centre for the training of pupil teachers.[2]

Relocation to South London

In 1907 the Board of Education determined that a mere basement was insufficient for a school. The threat of withdrawal of grant support caused the LCC to undertake to provide new buildings in Elm Park, between Tulse Hill and Brixton Hill in South London. In 1909 government of the school was handed over to a committee, which included LCC representatives.[2] As a condition of the incorporation of King's College into the University of London, under the terms of the King's College London (Transfer) Act 1908 (8 Edw. 7. c. xxxix), the civil service classes for adults had to be placed under separate administration, so Braginton agreed to make the necessary arrangements: he relinquished the headmastership in 1909, to run St George's College for women, Red Lion Square, and St George's College for men in Kingsway. R.B. Henderson took over as headmaster of Strand School in 1910, and he it was who supervised the move to South London in 1913.[2]

After the move to its new red brick premises, Strand flourished as a grammar school. Though its priority had been to prepare candidates for the civil service, it went on to offer courses leading to the Ordinary and Advanced level GCE examinations. Extra-curricular activities included a variety of sports such as football, cricket, swimming, athletics, boxing and fives. Games and social activities were organised on a House system, with boys being allocated a house on entering the school and thereafter being guided by a housemaster. There was active competition between the school's six houses: Arundel, Bedford, Exeter, Kings, Lancaster, and Salisbury. These are the names of streets off the Strand, plus Kings College. Salisbury Street no longer exists.[4] The school had an annual sports day, which was held on the school field until 1952, when Tulse Hill Comprehensive was built there.[5]

There were a number of societies, including a debating society, a dramatic society and, in later years, a film society. The cadet force, had air force and army sections, the latter affiliated to the Kings Royal Rifle Corps.[3] The school published each July and December The Strand School Magazine. A printing press in the gallery above the main hall turned out three school calendars a year, one for each term, visiting cards, membership cards for school societies and letter-headings, as well as programmes for school plays.[6]

1936: Tragedy in the Black Forest

The school suffered a major tragedy on 17 April 1936 when a hiking party of 27 were caught in a blizzard in the Black Forest, near Freiburg, Germany, and five boys froze to death. They had set out on a three-hour hike between hostels, via Schauinsland, 4200 feet.[7] The master in charge, Kenneth Keast ignored local terrain, the weather reports indicating severe weather, and multiple warnings from locals, directing his group up the steepest flank of the Schauinsland in severe weather, ultimately stranding his group on the southeastern mountain flank.[8] The event was used by the Nazi regime as a propaganda tool in which Keast was absolved from blame. Initially commended for his courage by the London County Council's committee of enquiry,[9] subsequent investigative reports, including a 2016 article in The Guardian highlighted the negligence of the master in charge. [10]

In 1938 the Engländerdenkmal ("Monument to Englishmen") of architect Hermann Alker was erected by the Hitler Youth in commemoration.[11]

World War II

During the Second World War Strand School was evacuated to Effingham in Surrey.

Crossword security alarm

The school in 1944, via its then-headmaster Leonard Dawe, was involved in what became known as the D-Day Daily Telegraph crossword security alarm.

1956: Tulse Hill Comprehensive School and the final years

Strand served its surrounding area for most of the twentieth century as the local boys' grammar school, with nearby St Martin-in-the Fields High School providing for girls.

In the mid-1950s came the first serious threat to Strand School's existence, when two large comprehensive schools were opened locally: Dick Sheppard School for girls in 1955,[12] and the giant Tulse Hill School for boys in 1956, the latter built on what had been the Strand playing fields.[13] Only by a narrow margin – following an intense campaign by parents, old boys and school governors – had the school beaten off a plan to abolish it as a grammar school, and turn it into one of the two comprehensives: what became Tulse Hill Comprehensive was to have been known as "Strand Comprehensive."

The successful campaign provided what was to prove, in the end, only temporary respite. With the abolition of the tripartite system in education, the Inner London Education Authority took the decision to go fully comprehensive. So in 1972 the ILEA again proposed that Strand, described by Labour's Roy Hattersley as a "small maintained boys' grammar school in an elderly building," be turned into a comprehensive; its pupils were to be transferred to Dick Sheppard, with the Strand and Tulse Hill buildings merged to form a single new comprehensive school. Battle once again commenced.

Margaret Thatcher, at the time Secretary of State for Education, later approved the closure, but not the Tulse Hill School alterations. Strand parents this time chose to contest the closure in the courts: in May 1972 an injunction was granted forbidding closure. The Labour-controlled ILEA was forced to abandon immediate closure of Strand, but made a second application to the minister in July 1972.

Thatcher turned down this application in January 1973, saying that the change of heart was because she had "listened to the parents and watched their fight to save a small school which provided an opportunity for anyone who got there on a basis of merit, whatever his background."[14]

Around 1979 Strand School was closed down.[15] Its remnants were merged with Dick Sheppard School, which became, for the time that remained, a mixed school. Of all four schools, the only one to survive the rigours of improvement and shifting education policy was St Martin-In-The-Fields High School for Girls. Tulse Hill School closed in 1990, and Dick Sheppard School in 1994.

Subsequent history of the building

After Strand School's closure, the buildings became known as the Strand Centre and had various uses. They were used as temporary premises for schools being renovated and by an Albanian Youth Group.[16] In 2000 they were converted for use as a primary school to temporarily house Brockwell Primary School, while the new Jubilee Primary School was being built on Brockwell's site. When Jubilee Primary finally opened in 2003 the Strand premises again fell vacant.

2009, Elm Court School

In 2007, to house Elm Court School, major renovation were made at the former Strand School site.[17] Elm Court is a special educational needs school with capacity for 100 pupils at key stages 3 and 4,[18] "aged 9 to 19 years who have learning difficulties with associated social and communication needs. Many ... pupils have autism".[19] The school moved from Elmcourt Road in West Norwood to make way for the new Elmgreen secondary school. Elm Court School opened in Elm Park SW2 in March 2009.[18]

The school's architecture

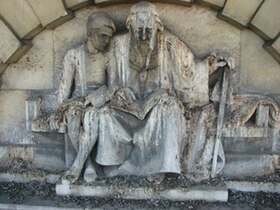

The buildings near the southern end of Elm Park were built by the London County Council between 1912 and 1914 under the direction of the chief architect W.E. Riley.[20] The style employed was Edwardian, with a red brick frontage decorated with Portland stone dressings, enlivened by a central stone arched window incorporating a sculpture.[20]

Other features of the school were its main hall with its war memorial to pupils and former pupils who died in the First and Second World Wars, in the form of a large organ bought by public subscription, the gymnasium at the rear of the main building, and, on the top floor, what were laboratories and the dining hall.[3] In the 1960s a two-storey art and woodkwork/metalwork block was built next to the gymnasium.

The school has been described as, "one of the finest secular buildings in terms of its architectural quality and character" and, "a splendid local landmark of significant historic and architectural interest in its own right."[20] A less obvious feature is[when?] the two fives courts located behind the school. These are similar to those required for Rugby fives. A photograph showing the right hand court in use (from 1914) exists in the Frith Collection.

Headmasters

Brixton from 1913

- Bernard Fenton, 1974-1979

- Martin Reed, 1969-1974

- J. E. Cox, headmaster: 1956–1969. Died during summer holidays in 1969 whilst still Headmaster.[21][additional citation(s) needed]

- Leonard Dawe (1889–1963): 1926–56.[22]

- Ronald Gurner (1890–1939): 1920–26.[23]

- R. B. Henderson: September 1913 – 1919.[24]

King's College, from 1893

- Ralph Bushill Henderson: 1911–13.[25] He then continued at Brixton.

- William Braginton: 1893–1910.[26]

Notable former pupils

Former pupils are known as Old Strandians.[3] They include the following:

- Rev. Donald Aird, Vicar of St Marks Church, Hamilton Terrace, London NW8 (1979–1995), founder of the Society of Christians and Jews.

- Vernon Butcher, Organist of the Chapel Royal.[27]

- David Guthrie Catcheside, seminal figure in the development of post-war genetics.[28]

- Charles Alfred Fisher, Professor of Geography, School of Oriental & African Studies.[29]

- Fruitbat (Les Carter), rock musician, co-founder of Carter USM.

- Leonard Christopher Gilley, artist.[30]

- Sir Reg Goodwin, politician and former Leader of the Greater London Council.

- Leonard Hussey, explorer.[31]

- David Jacobs, CBE, broadcaster, long-time presenter of BBC's Juke Box Jury and Any Questions.[14]

- Lord Sydney Jacobson, newspaper executive and editor.

- George Barker Jeffery, mathematical physicist, translator of papers by Einstein, Lorentz & other fathers of relativity theory.[32]

- Mick Jones, rock musician, lead guitarist and vocalist, The Clash.[33]

- James Lovelock, CH, CBE, FRS, scientist and environmentalist, best known for the Gaia hypothesis.[34]

- Richard Valentine Moore, winner of the George Cross.[35]

- Sir Arnold Plant, economist.[36]

- Leroy Rosenior, professional footballer, coach and broadcaster.

- Tim Roth, Academy award-nominated, BAFTA-winning movie actor and director

- Jeremy Spencer, rock musician, founder-member of Fleetwood Mac.[37]

- Euan Uglow, artist.[30]

- Colin Hyams, Mayor of Huntingdon 2012–2013

References

- ^ a b c "Strand School/ King's College London Archives". Archived from the original on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Keith Dakin-White, 'History of Strand School, 1875–1913', written for MA in Science Education, Chelsea College, University of London, 1984

- ^ a b c d London County Council, (1962), Secondary Schools in Bermondsey, Lambeth and Southwark, Division 8, page 22

- ^ "The Strand, southern tributaries – continued", British History online

- ^ The Strand School Magazine, Vol. XII, no. 8, December 1953, p. 19.

- ^ The Strand, Vol. X11, no. 13, July 1956, p. 29.

- ^ The Times, 20 April 1936, p. 15.

- ^ "Fatal hike became a nazi propaganda coup" by Kate Connolly, The Guardian online

- ^ The Times, 20 May 1936, p. 13.

- ^ "Fatal hike became nazi propaganda coup" by Kate Connolly, The Guardian online

- ^ Egon Schwär: Sagen in Oberried und seinen Ortsteilen Hofsgrund, St. Wilhelm, Zastler und Weilersbach. 3. Auflage. Freiburger Echo Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-86028-199-4, S. 60; The Times, 9 Nov 1938, p. 11.

- ^ London County Council, (1962), Secondary Schools in Bermondsey, Lambeth and Southwark, Division 8

- ^ London County Council, Secondary Schools: Division 8, April 1962, page 24.

- ^ a b House of Commons Speech by Margaret Thatcher (Secondary Education (Opposition motion)), (1 February 1973), (Hansard HC [849/1639-68])

- ^ "King's College, London archives, show pupils' details 1946–1979". Archived from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ Lambeth Planning Applications Committee, Case No. 06/02778/RG3, Page 100, (Lambeth Planning)

- ^ Lambeth Planning Applications Committee, Case 06/02778/RG3 The Strand Centre, (2006), (Lambeth Planning)

- ^ a b › Services

- ^ Elm Court School

- ^ a b c Edmund Bird, (January 1997), Consultation Draft Report & Character Assessment Statement for the Proposed Brixton Hill Conservation Area, (London Borough of Lambeth Environmental Services)

- ^ The Strand, Vol. XII, no. 13, July 1956, p. 3.

- ^ Holley, Duncan; Chalk, Gary (1992). The Alphabet of the Saints. ACL & Polar Publishing. p. 97. ISBN 0-9514862-3-3.

- ^ The Times, 10 March 1920, p, 13.

- ^ The Times, 13 December 1911, p. 11.

- ^ The Times, 16 February 1911, p. 11.

- ^ The Times, 16 Dec 1910, p. 12.

- ^ Watkins Shaw, The Succession of Organists of the Chapel Royal and the Cathedrals of England and Wales from c. 1538, Also of the Organists of the Collegiate Churches of Westminster and Windsor, Certain Academic Choral Foundations, and the Cathedrals of Armagh and Dublin, (1991), (Oxford Univ Pr)

- ^ Australian Academy of Science

- ^ Obituary: Charles Alfred Fisher, MA, D. Lit., 1916–1982 The Geographical Journal, Vol. 148, No. 2 (Jul., 1982), pp. 296–297: [1]

- ^ a b Dolman, Bernard, (1927), Who's who in Art, (Art Trade Press)

- ^ HMS ENDURANCE Visit and Learn website Archived 26 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Royal Society (Great Britain), (1955), Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, (Royal Society (Great Britain)

- ^ "Mick Jones: interview - Time Out London 40th birthday heroes". Archived from the original on 17 November 2015.

- ^ Lovelock's autobiography

- ^ George Cross Database

- ^ Ronald Henry Coase, (1995), Essays on Economics and Economists, Page 176, (University of Chicago Press)

- ^ "An Interview with Jeremy Spencer of Fleetwood Mac: True blues music seems to have a healing quality for the heart".

External links