Sting (musician)

Sting | |

|---|---|

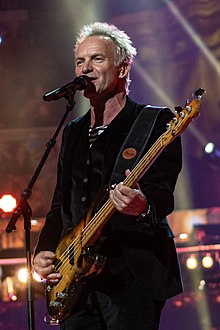

Sting in 2018 | |

| Born | Gordon Matthew Thomas Sumner 2 October 1951 Wallsend, England |

| Alma mater | Northern Counties College of Education |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1969–present |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 6, including Joe, Mickey and Eliot |

| Awards | Full list |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | |

| Formerly of | |

| Website | sting |

| Signature | |

| |

Gordon Matthew Thomas Sumner (born 2 October 1951), known as Sting, is an English musician, activist and actor. He was the frontman, principal songwriter and bassist for new wave band the Police from 1977 until their breakup in 1986. He launched a solo career in 1985 and has included elements of rock, jazz, reggae, classical, new-age, and worldbeat in his music.[4]

Sting has sold a combined total of more than 100 million records as a solo artist and as a member of the Police.[5][6] He has received three Brit Awards, including Best British Male Artist in 1994 and Outstanding Contribution to Music in 2002; a Golden Globe; an Emmy; and four Academy Award nominations.[7] As a solo musician and as a member of the Police, Sting has received 17 Grammy Awards.[8] He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of the Police in 2003. Sting has received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame; the Ivor Novello Award for Lifetime Achievement from the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors; a CBE from Queen Elizabeth II for services to music; Kennedy Center Honors;[9] and the Polar Music Prize.[10] In May 2023, he was made an Ivor Novello Fellow.[6]

Early life

Gordon Matthew Thomas Sumner was born at Sir G B Hunter Memorial Hospital in Wallsend, Northumberland, England, on 2 October 1951,[11][12][13] the eldest of four children of Audrey (née Cowell), a hairdresser, and Ernest Matthew Sumner, a milkman and former fitter at an engineering works.[14] He grew up near Wallsend's shipyards, which made an impression on him. As a child, he was inspired by the Queen Mother waving at him from a Rolls-Royce to divert from the shipyard prospect towards a more glamorous life.[15][16] He helped his father deliver milk and by ten was "obsessed" with an old Spanish guitar left by an emigrating friend of his father.[17]

Sting attended St Cuthbert's Grammar School in Newcastle upon Tyne. He visited nightclubs such as Club A'Gogo to see Cream and Manfred Mann, who influenced his music.[18] He learned to sing and play simultaneously by listening to records at 78 rpm.[19] After leaving school in 1969, he enrolled at the University of Warwick in Coventry, but left after a term. After working as a bus conductor, building labourer, and tax officer, he attended the Northern Counties College of Education (now Northumbria University) from 1971 to 1974 and qualified as a teacher.[20] He taught at St Paul's First School in Cramlington for two years.[21]

Sting performed jazz in the evenings, on weekends, and during breaks from college and teaching, playing with the Phoenix Jazzmen, Newcastle Big Band and Last Exit.[22] He gained his nickname after his habit of wearing a black and yellow jumper with hooped stripes with the Phoenix Jazzmen. Bandleader Gordon Solomon thought he looked like a bee (or according to Sting himself, "they thought I looked like a wasp"), which prompted the name "Sting".[23][24] In the 1985 documentary Bring On the Night a journalist called him Gordon, to which he replied, "My children call me Sting, my mother calls me Sting, who is this Gordon character?"[25] In 2011, he told Time that "I was never called Gordon. You could shout 'Gordon' in the street and I would just move out of your way".[26] Despite this, he chose not to legally change his name to "Sting".[27]

Musical career

1977–1984: The Police and early solo work

In January 1977, Sting joined Stewart Copeland and Henry Padovani (soon replaced by Andy Summers) to form the Police, becoming the band's lead singer, bass player, and primary songwriter. From 1978 to 1983, the Police had five UK chart-topping albums, won six Grammy Awards and won two Brit Awards (for Best British Group and for Outstanding Contribution to Music).[28][29] Their initial sound was punk-inspired, but they switched to reggae rock and minimalist pop. Their final album, Synchronicity, was nominated for five Grammy Awards including Album of the Year in 1983. It included their most successful song, "Every Breath You Take", written by Sting.

Even though logic would say, "Are you out of your mind? You're in the biggest band in the world – just bite the bullet and make some money." But there continued to be some instinct, against logic, against good advice, [that] told me I should quit.

According to Sting, appearing in the documentary Last Play at Shea, he decided to leave the Police while onstage during a concert of 18 August 1983 at Shea Stadium in New York City because he felt that playing that venue was "[Mount] Everest".[31] While never formally breaking up, after Synchronicity, the group agreed to concentrate on solo projects.[32] As the years went by, the band members, especially Sting, dismissed the possibility of reforming. In 2007, however, the band did reform temporarily for the purpose of undertaking a reunion tour.[33]

Four of the band's five studio albums appeared on Rolling Stone's list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time and two of the band's songs, "Every Breath You Take" and "Roxanne", each written by Sting, appeared on Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.[34] In addition, "Every Breath You Take" and "Roxanne" were among the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's 500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll. In 2003, the band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[35] They were also included in Rolling Stone's and VH1's lists of the "100 Greatest Artists of All Time".[36][37]

In 1978, Sting collaborated with members of Hawkwind and Gong as the Radio Actors on the one-off single "Nuclear Waste".[38] In September 1981, Sting made his first live solo appearance, on all four nights of the fourth Amnesty International benefit The Secret Policeman's Other Ball in London's Drury Lane theatre at the invitation of producer Martin Lewis. He performed solo versions of "Roxanne" and "Message in a Bottle". He also led an all-star band (dubbed "the Secret Police") on his own arrangement of Bob Dylan's "I Shall Be Released". The band and chorus included Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Robin Gibb, Cliff Richard, Phil Collins, Bob Geldof and Midge Ure, all of whom (except Beck and Gibb) later performed at Live Aid. His performances were in the album and movie of the show. The Secret Policeman's Other Ball began his growing involvement in political and social causes.[citation needed] In 1982 he released a solo single, "Spread a Little Happiness" from the film of the Dennis Potter television play Brimstone and Treacle. The song was a reinterpretation of the 1920s musical Mr. Cinders by Vivian Ellis and a Top 20 hit in the UK.[39]

1985–1989: Solo debut

His first solo album, 1985's The Dream of the Blue Turtles, featured jazz musicians including Kenny Kirkland, Darryl Jones, Omar Hakim and Branford Marsalis. It included the hit singles "If You Love Somebody Set Them Free" (backed with the non-LP song "Another Day"), "Fortress Around Your Heart", "Love Is the Seventh Wave" and "Russians", the latter of which was based on a theme from the Lieutenant Kijé Suite.[40] Within a year, the album reached Triple Platinum. The album received Grammy nominations for Album of the Year, Best Male Pop Vocal Performance, Best Jazz Instrumental Performance and Best Engineered Recording.[41]

In November 1984, Sting was part of Band Aid's "Do They Know It's Christmas?", which raised money for famine victims in Ethiopia.[42] Released in June 1985, Sting sang the line "I Want My MTV" on "Money for Nothing" by Dire Straits.[43] In July 1985, Sting performed Police hits at the Live Aid concert at Wembley Stadium in London. He also joined Dire Straits in "Money for Nothing" and he sang two duets with Phil Collins.[44][45] In 1985, Sting provided spoken vocals for the Miles Davis album You're Under Arrest, taking the role of a French-speaking police officer. He also sang backing vocals on Arcadia's single "The Promise", on two songs from Phil Collins' album No Jacket Required, and contributed "Mack the Knife" to the Hal Willner-produced tribute album Lost in the Stars: The Music of Kurt Weill. In September 1985, he performed "If You Love Somebody Set Them Free" at the 1985 MTV Video Music Awards at the Radio City Music Hall in New York.[46] The 1985 film Bring On the Night, directed by Michael Apted, documented the formation of his solo band and its first concert in France.[47]

Sting released ...Nothing Like the Sun in 1987, including singles, "We'll Be Together", "Fragile", "Englishman in New York" and "Be Still My Beating Heart", dedicated to his mother, who had recently died. It went Double Platinum. "The Secret Marriage" from this album was adapted from Hanns Eisler and "Englishman in New York" was about Quentin Crisp. The album's title is from William Shakespeare's Sonnet 130.[48] The album won Best British Album at the 1988 Brit Awards and in 1989 received three Grammy nominations including his second consecutive nomination for Album of the Year. "Be Still My Beating Heart" earned nominations for Song of the Year and Best Male Pop Vocal Performance. In 1989, ...Nothing Like the Sun was ranked number 90 and his Police album Synchronicity was ranked number 17 on Rolling Stone's 100 greatest albums of the 1980s.[49]

In February 1988, he made Nada como el sol, four songs from Nothing like the Sun he sang in Spanish and Portuguese. In 1987, jazz arranger Gil Evans placed him in a big band setting for a live album of Sting's songs, and on Frank Zappa's 1988 Broadway the Hard Way he performed an arrangement of "Murder by Numbers", set to "Stolen Moments" by Oliver Nelson and dedicated to evangelist Jimmy Swaggart. In October 1988 he recorded a version of Igor Stravinsky's The Soldier's Tale with the London Sinfonietta conducted by Kent Nagano. It featured Vanessa Redgrave, Ian McKellen, Gianna Nannini and Sting as the soldier.[50]

1990–1997: Greater solo success

His 1991 album, The Soul Cages, was dedicated to his late father. It included "All This Time" and the Grammy-winning title track. The album, which went platinum, included an Italian version of "Mad About You".[citation needed] Also in 1991, he appeared on Two Rooms: Celebrating the Songs of Elton John and Bernie Taupin. He performed "Come Down in Time" for the album, which also features other popular artists and their renditions of John/Taupin songs.[citation needed]

In England, our house is surrounded by barley fields, and in the summer it's fascinating to watch the wind moving over the shimmering surface, like waves on an ocean of gold. There's something inherently sexy about the sight, something primal, as if the wind were making love to the barley. Lovers have made promises here, I'm sure, their bonds strengthened by the comforting cycle of the seasons.

Sting's fourth album Ten Summoner's Tales peaked at two in the UK and US album charts in 1993 and went triple platinum in just over a year.[39][52] The album was recorded at his Elizabethan country home, Lake House in Wiltshire. Ten Summoner's Tales was nominated for the Mercury Prize in 1993 and for the Grammy for Album of the Year in 1994. The title is a wordplay on his surname, Sumner and "The Summoner's Tale", one of The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer. Hit singles on the album include "Fields of Gold", a song inspired by the barley fields next to his Wiltshire home, with the music video featuring a silhouette of Sting walking through a village containing common features seen throughout the UK during that time such as a red telephone box and "If I Ever Lose My Faith in You", the latter earning his second award for best male pop singer at the 36th Grammy Awards.[53]

In May 1993, he covered his own Police song from the Ghost in the Machine album, "Demolition Man", for the Demolition Man film. With Bryan Adams and Rod Stewart, Sting performed "All for Love" for the film The Three Musketeers. The song stayed at the top of the U.S. charts for three weeks, topped multiple other charts worldwide and reached number two in the UK. In February, he won two Grammy Awards and was nominated for three more.[53] Berklee College of Music awarded him his second honorary doctorate of music in May. In November, he released the compilation, Fields of Gold: The Best of Sting, which was certified Double Platinum. That year, he sang with Vanessa Williams on "Sister Moon" and appeared on her album The Sweetest Days. At the 1994 Brit Awards in London, he was Best British Male.[54]

Sting's 1996 album, Mercury Falling debuted strongly, with the single "Let Your Soul Be Your Pilot" reaching number 15 in the UK Singles Chart, but the album soon dropped from the charts. He reached the UK Top 40 with two further singles the same year with "You Still Touch Me" (number 27 in June) and "I Was Brought To My Senses" (number 31 in December). The song "I'm So Happy I Can't Stop Crying" from this album also became a US country music hit in 1997 in a version with Toby Keith. Sting recorded music for the Disney film Kingdom of the Sun, which was reworked into The Emperor's New Groove. The film's overhauls and plot changes were documented by Sting's wife, Trudie Styler, as the changes resulted in some songs not being used.[55]

On 4 September 1997, Sting performed "I'll Be Missing You" with Puff Daddy at the 1997 MTV Video Music Awards in tribute to Notorious B.I.G.[56] On 15 September 1997, Sting appeared at the Music for Montserrat concert at the Royal Albert Hall, London, performing with fellow English artists Paul McCartney, Elton John, Eric Clapton, Phil Collins and Mark Knopfler.[57]

1998–2005: Brand New Day and soundtrack work

A period of relative musical inactivity followed from 1997, before Sting eventually re-emerged in September 1999, with a new album Brand New Day, which gave him two more UK Top 20 hits in the title track "Brand New Day" (a UK number 13 hit featuring Stevie Wonder on harmonica) and "Desert Rose" (a UK number 15 hit). The album went Triple Platinum by January 2001. In 2000, he won Grammy Awards for Brand New Day and the song of the same name. At the awards ceremony, he performed "Desert Rose" with his collaborator on the album version, Cheb Mami.

In 2000, the soundtrack for The Emperor's New Groove was released with complete songs from the previous version of the film. The final single used to promote the film, "My Funny Friend and Me", was Sting's first nomination for an Academy Award for Best Song.[53]

In February 2001, he won another Grammy for "She Walks This Earth (Soberana Rosa)" on A Love Affair: The Music Of Ivan Lins. His "After the Rain Has Fallen" made it into the Top 40. His next project was a live album at his villa in Figline Valdarno, released as a CD and DVD as well as being broadcast on the internet. The CD and DVD were to be entitled On Such a Night and intended to feature re-workings of Sting favourites such as "Roxanne" and "If You Love Somebody Set Them Free". The concert, scheduled for 11 September 2001, was altered due to the terrorist attacks in America that day. The webcast shut after one song (a reworked version of "Fragile"), after which Sting let the audience decide whether to continue the show. They decided to go ahead and the album and DVD appeared in November as ...All This Time, dedicated "to all those who lost their lives on that day". He performed "Fragile" with Yo-Yo Ma and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir during the opening ceremonies of the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City, Utah, US.[58]

In 2002, he won a Golden Globe Award for "Until..." from the film Kate & Leopold.[53] Written and performed by him, "Until..." was his second nomination for an Academy Award for Best Song.[53] At the 2002 Brit Awards in February, Sting received the prize for Outstanding Contribution to Music.[54] In May 2002 he received the Ivor Novello Award for Lifetime Achievement from the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors.[59] In the Queen's Birthday Honours 2003 Sting was made a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire For services to the Music Industry.[60] At the 54th Primetime Emmy Awards in September, Sting won an Emmy Award for Outstanding Individual Performance in a Variety Or Music Program, for his A&E special, Sting in Tuscany... All This Time.[53]

In 2003, Sting released Sacred Love, a studio album featuring collaborations with hip-hop artist Mary J. Blige and sitar performer Anoushka Shankar. He and Blige won a Grammy for their duet, "Whenever I Say Your Name". The song is based on Johann Sebastian Bach's Praeambulum 1 C-Major (BWV 924) from the Klavierbuechlein fuer Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, though Sting said little about this adaptation.[61] In 2004, he was nominated for the third time for an Academy Award for Best Song,[53] for "You Will Be My Ain True Love", from Cold Mountain, sung in duet with Alison Krauss. The pair performed the song at the 76th Academy Awards.[62]

His autobiography Broken Music was published in October. He embarked on a Sacred Love tour in 2004 with performances by Annie Lennox.[63] Sting went on the Broken Music tour, touring smaller venues, with a four-piece band, starting in Los Angeles on 28 March 2005 and ending on 14 May 2005. Sting was on the 2005 Monkey Business CD by hip-hop group the Black Eyed Peas, singing on "Union", which samples his Englishman in New York. Continuing with Live Aid, he appeared at Live 8 at Hyde Park, London in July 2005.[64]

2006–2010: Experimental albums and the Police reunion

In 2006, Sting was on the Gregg Kofi Brown album, with "Lullaby to an Anxious Child" produced and arranged by Lino Nicolosi and Pino Nicolosi of Nicolosi Productions.[65]

In October 2006, he released an album entitled Songs from the Labyrinth featuring the music of John Dowland (an Elizabethan-era composer) and accompaniment from Bosnian lute player Edin Karamazov. Sting's interpretation of this English Renaissance composer and his cooperation with Edin Karamazov brought recognition in classical music.[66] As promotion of this album, he appeared on the fifth episode of Studio 60 to perform a segment of Dowland's "Come Again" as well as his own "Fields of Gold" in arrangement for voice and two archlutes.

On 11 February 2007, he reunited with Police to open the 2007 Grammy Awards, singing "Roxanne", and announced a reunion tour, the first concert of which was in Vancouver on 28 May 2007 for 22,000 fans. The Police toured for more than a year, beginning with North America and crossing to Europe, South America, Australia, New Zealand and Japan. Tickets for the British tour sold out within 30 minutes, the band playing two nights at Twickenham Stadium, southwest London on 8 and 9 September 2007.[67] The last concert was at Madison Square Garden on 7 August 2008, during which his three daughters appeared with him.[citation needed]

"Brand New Day" was the final song of the night for the Neighborhood Ball, one of ten inaugural balls honouring President Barack Obama on Inauguration Day, 20 January 2009. Sting was joined by Stevie Wonder on harmonica.[68]

Sting entered the studio in early February 2009 to begin work on a new album, If on a Winter's Night...,[69] released in October 2009.[70] Initial reviews by fans that had access to early promotional copies were mixed, and some questioned Sting's artistic direction with this album.[71] In 2009, Sting appeared at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame 25th anniversary concert, playing "Higher Ground" and "Roxanne" with Stevie Wonder and "People Get Ready" with Jeff Beck.[72][73] Sting himself was inducted in 2003, as a member of the Police.[74][75]

In October 2009, Sting played a concert in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, for an arts and cultural festival organised by the Forum of Culture and Arts of Uzbekistan Foundation. Despite claiming he thought the concert was sponsored by UNICEF, he faced criticism in the press for receiving a payment of between one and two million pounds from Uzbek president Islam Karimov for the performance. Karimov is accused by the UN and Amnesty of human rights abuses and UNICEF stated they had no connection with the event.[76]

2010–2016: The Last Ship and joint tours with Paul Simon and Peter Gabriel

In 2010–2011, Sting continued his Symphonicity Tour, touring South Korea, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, South America and Europe.[77] In the second half of 2011, Sting began his Back to Bass Tour, which would continue (with periodic breaks) through 2013.[78] In October 2010, Sting played two concerts in Arnhem, Netherlands, for Symphonica in Rosso. In 2011, Time magazine named Sting one of the 100 most influential people in the world.[79] On 26 April he performed "Every Breath You Take", "Roxanne" and "Desert Rose" at the Time 100 Gala in New York City.[80]

Sting recorded a song called "Power's Out" with Nicole Scherzinger. The song, originally recorded in 2007, was to have been included on Scherzinger's shelved album Her Name is Nicole. The song was released on Scherzinger's 2011 debut album Killer Love. Sting recorded a new version of the song "Let Your Soul Be Your Pilot" as a duet with Glee actor/singer Matthew Morrison, which appears on Morrison's 2011 eponymous debut album.[81] On 15 September 2011, Sting performed "Fragile" at the 92nd Street Y in New York City, to honour the memory of his friend, financier-philanthropist Herman Sandler, who died in the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center.[82]

For several years, Sting worked on a musical, The Last Ship, inspired by Sting's own childhood experiences and the shipbuilding industry in Wallsend.[83] The Last Ship tells a story about the demise of the British shipbuilding industry in 1980s Newcastle and debuted in Chicago in June 2014 before transferring to Broadway in the autumn.[84][85][86] Sting's eleventh studio album, titled The Last Ship and inspired by the play, was released on 24 September 2013.[87][88] The album features guest artists with roots in northeast England, including Brian Johnson, vocalist from AC/DC.[89]

In February 2014, Sting embarked on a joint concert tour titled On Stage Together with Paul Simon, playing 21 concerts in North America.[90] The tour continued in early 2015, with ten shows in Australia and New Zealand,[91][92] and 23 concerts in Europe,[93] ending on 18 April 2015. On 26 June 2015 in Bergen, Norway (at the Bergen Calling Festival), Sting embarked on a 21-date Summer 2015 solo tour of Europe in Trondheim, Norway (at the Olavsfestdagene), visiting Denmark, France, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Italy and Sweden.[94]

On 28 August 2015, "Stolen Car", a duet with French singer Mylène Farmer was released.[95] It is a cover from Sting's 2003 seventh solo studio album Sacred Love and will serve as the first single from Farmer's tenth studio album, Interstellaires.[96] On its release, the song went straight to number one over French iTunes music download charts, subsequently hitting number one on the main French singles chart and giving Sting his first number one in France.[97] In 2016, Sting performed a 19-date joint concert summer tour of North America with Peter Gabriel.[98]

2016–2020: 57th & 9th, 44/876 and My Songs

On 18 July 2016, Sting's first rock album in many years was announced. 57th & 9th was released on 11 November 2016. The title is a reference to the New York City intersection he crossed every day to get to the studio where much of the album was recorded.[99][100] It has contributions by long-time band members Vinnie Colaiuta and Dominic Miller, and Jerry Fuentes and Diego Navaira of the Last Bandoleros. The album was produced by Sting's manager, Martin Kierszenbaum. On 9 November 2016, Sting performed two shows at Irving Plaza, in Manhattan, New York City, playing songs from 57th & 9th for the first time live in concert: a "57th & 9th iHeartRadio Album Release Party" show and a Sting Fan Club Member Exclusive Show later that night.[101][102] Named the 57th & 9th Tour, a world tour of theatres, clubs and arenas in support of 57th & 9th (with special guests Joe Sumner and the Last Bandoleros) began on 1 February 2017 in Vancouver at the Commodore Ballroom and continued into October.[103][104]

On 4 November 2016, management of the Bataclan theatre announced that Sting would perform an exclusive concert in Paris on 12 November 2016 for the re-opening of the Bataclan, a year after the terrorist attack at the venue.[105] The Police's former guitar player, French native Henry Padovani, joined the band on stage for "Next to You", one of the encores.[nb 1][106]

Sting was announced as the joint winner of the 2017 Polar Music Prize, a Swedish international award given in recognition of excellence in the world of music. The award committee stated: "As a composer, Sting has combined classic pop with virtuoso musicianship and an openness to all genres and sounds from around the world."[10] In 2018, he scheduled a musical and story-telling performance at the Metropolitan Museum of Art honouring Hudson River School artist Thomas Cole.[107]

For the first time in 22 years, BMI has a new top song in our repertoire with Sting's timeless hit "Every Breath You Take", a remarkable achievement that solidifies its place in songwriting history.

On 7 February 2018, Sting performed as special guest at the Italian Sanremo Music Festival, singing "Muoio per te", the Italian version of "Mad About You", the lyrics of which were written by his friend and colleague Zucchero Fornaciari and "Don't Make Me Wait" with Shaggy. 44/876, Sting and Shaggy's first studio album as a duo,[109] was released in April 2018. On 21 April 2018, Sting was among the artists to perform at The Queen's Birthday Party held at the Royal Albert Hall.[110] In 2019, he received a BMI Award when "Every Breath You Take", a hit single by the Police, became the most-played song in radio history.[111]

Sting's fourteenth album, titled My Songs, was released on 24 May 2019. The album features 14 studio (and one live) re-recorded versions of his songs released throughout his solo career and his time with the Police.[112][113] In support of the album, a world tour named the My Songs Tour started on 28 May 2019 at La Seine Musicale in Paris and ended on 2 September 2019 at Kit Carson Park in Taos, New Mexico.[114] A 16-date residency from 22 May to 2 September 2020 at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, Nevada was rescheduled due to COVID-19, with the first date taking place on 29 October 2021.[115][116] His 6 nights at the London Palladium were rescheduled to April 2022.[117]

On 14 April 2020, Sting recorded a duet cover of "Message in a Bottle" with the girl group All Saints.[118] The same year, he appeared on the song "Simple" available on the EP Pausa by Ricky Martin.[119] Also in 2020, Sting was listed as number 32 on Rolling Stone's list of the top 50 greatest bassists of all time.[120]

2021–present: Duets and The Bridge

On 19 March 2021, Sting released Duets, a compilation album comprising 17 tracks of collaborations with various artists including Eric Clapton, Mary J. Blige, Shaggy, Annie Lennox and Sam Moore.[121]

Sting released his fifteenth studio album The Bridge on 19 November 2021. It was preceded by the release of the lead single "If It's Love" on 1 September 2021. Sting wrote the set of pop-rock songs "in a year of global pandemic, personal loss, separation, disruption, lockdown and extraordinary social and political turmoil".[122][123] On 20 November 2021, Sting's single "What Could Have Been", with Ray Chen, was featured in the third act of the League of Legends animated series Arcane; this single was released the same day.[124][125] Sting then opened The Game Awards 2021 with the song;[126] Todd Marten, for the Los Angeles Times, wrote "The Game Awards began this year with an opening that might have launched the Grammy Awards".[127]

In February 2022, Sting collaborated with Swedish DJ supergroup Swedish House Mafia, releasing a song and music video titled "Redlight". The song used lyrics from the Police's 1979 hit "Roxanne" with a dark electronic feeling. Sting made an appearance in the music video, the song being part of the new album from Swedish House Mafia titled Paradise Again.[128] In February 2022, it was announced that Universal Music Group purchased Sting's catalogue of solo works and those with the Police for an undisclosed amount.[129] Forbes ranked him as the highest-paid solo musician of 2022, with an estimated earnings of $210 million.[130]

The Wall Street Journal reported that Sting gave a private performance on 17 January 2023 for fifty top Microsoft executives at the 2023 World Economic Forum at Davos. The next day Microsoft announced plans to lay off 10,000 people in what some employees called "as a bad look" for the company. "Some employees thought it wasn't the right time for a company-sponsored Sting concert," wrote Tom Dotan and Sam Schechner. "The theme of the event was sustainability."[131] The event quickly went viral.[132]

Activism

Sting's involvement in human rights began in September 1981, when Martin Lewis included him in the fourth Amnesty International gala, The Secret Policeman's Other Ball, a benefit show co-founded by Monty Python member John Cleese.[133] Sting states, "before [the Ball] I did not know about Amnesty, I did not know about its work, I did not know about torture in the world."[134] Following the example set at the 1979 show by Pete Townshend, Sting performed "Roxanne" and "Message in a Bottle" appearing on all four nights at Theatre Royal in London. He also led other musicians (The Secret Police) including Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Phil Collins, Donovan, Bob Geldof and Midge Ure in the finale – Sting's reggae-tinged arrangement of Bob Dylan's "I Shall Be Released". The event was the first time that Sting worked with Geldof. His association with Amnesty continued throughout the 1980s and beyond and he took part in Amnesty's human rights concerts.[135]

Sting had shown his interest in social and political issues in his 1980 song "Driven to Tears", an indictment of apathy to world hunger. In November 1984, he joined Band Aid, a charity supergroup primarily made up of the biggest British and Irish musicians of the era, and sang on "Do They Know It's Christmas?" which was recorded at Sarm West Studios in Notting Hill, London.[136] This led to the Live Aid concert in July 1985 at Wembley Stadium, in which Sting performed with Phil Collins and Dire Straits.[45] On 2 July 2005, Sting performed at the Live 8 concert at Hyde Park, London, the follow-up to 1985's Live Aid.[64] In 1984, Sting sang a re-worded version of "Every Breath You Take", titled "Every Bomb You Make" for episode 12 of the first series of the British satirical puppet show Spitting Image. The video for the song shows the puppets of world leaders and political figures of the day, usually with the figure matching the altered lyrics.[137]

In June 1986, Sting reunited with the Police for the last three shows of Amnesty's six-date A Conspiracy of Hope concerts in the US. The day after the final concert, he told NBC's Today Show: "I've been a member of Amnesty and a support member for five years."[138] In 1988, he joined musicians including Peter Gabriel and Bruce Springsteen for a six-week Human Rights Now! tour commemorating the 40th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[135]

With his wife, Trudie Styler and Raoni Metuktire, a Kayapo Indian leader in Brazil, Sting founded the Rainforest Foundation Fund to help save the rainforests and protect indigenous peoples there. In 1989, he flew to the Altamira Gathering to offer support while promoting his charity.[139] His support continues and includes an annual benefit concert at Carnegie Hall, which has featured Billy Joel, Elton John, James Taylor and others. A species of Colombian tree frog, Dendropsophus stingi, was named after him for his "commitment and efforts to save the rainforest".[140] In 1988, the single "They Dance Alone (Cueca Sola)" chronicled the plight of the mothers, wives and daughters of the "disappeared", political opponents killed by the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile.[141]

On 15 September 1997, Sting joined Paul McCartney, Eric Clapton, Elton John, Phil Collins and Mark Knopfler at London's Royal Albert Hall for Music for Montserrat, a benefit for the Caribbean island devastated by a volcano. Sting and Styler were awarded the Peace Abbey Courage of Conscience award in Sherborn, Massachusetts, on 30 June 2000.[142] In September 2001, Sting took part in America: A Tribute to Heroes singing "Fragile" to raise money for families of victims of the 9/11 attacks in the US.[143] In February 2005, Sting performed the Leeuwin Estate Concert Series in Western Australia: the concert raised $4 million for the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami relief.[144][145][146]

In 2007, Sting joined Andy Summers and Stewart Copeland for the closing set at the Live Earth concert at Giants Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey. Joined by John Mayer and Kanye West, Sting and the Police ended the show singing "Message in a Bottle"[147] In 2008 Sting contributed to Songs for Tibet to support Tibet and the Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso.[148] On 22 January 2010, Sting performed "Driven to Tears" during Hope for Haiti Now.[149] On 25 April 2010, he performed on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. in the 40th anniversary celebration of Earth Day.[150] Sting is a patron of the Elton John AIDS Foundation.[151]

In 2011, Sting joined more than 30 others in an open letter to British Prime Minister David Cameron for "immediate decriminalisation of drug possession" if a policy review showed it had failed. Sting was quoted: "Giving young people criminal records for minor drug possession serves little purpose — it is time to think of more imaginative ways of addressing drug use in our society."[152]

On 4 July 2011, Sting cancelled a concert for the Astana Day Festival in Astana, Kazakhstan. Amnesty International convinced him to cancel due to concerns over the rights of Kazakh oil and gas workers and their families. On 2 November 2012, Sting appeared on Hurricane Sandy: Coming Together and sang a version of "Message in a Bottle" to raise funds for those affected by a storm on the east coast of the US that week. The show reportedly raised $23 million.[153] Sting also participated as a co-host and musician during the day-long 2015 Norwegian TV campaign, dedicated to the preservation of the rainforest.[154]

In August 2014, Sting was one of 200 public figures who were signatories to a letter to The Guardian expressing their hope that Scotland would vote to reject Scottish independence from the UK in September's referendum on the issue.[155]

Sting publicly opposed Brexit and supported remaining in the European Union. On 23 June 2016, in a referendum, the British public voted to leave. In October 2018, Sting was among a group of British musicians who signed an open letter sent to then Prime Minister Theresa May, drafted by Bob Geldof, calling for "a 2nd vote", stating that Brexit will "impact every aspect of the music industry. From touring to sales, to copyright legislation to royalty collation", the letter added: "We dominate the market and our bands, singers, musicians, writers, producers and engineers work all over Europe and the world and, in turn, Europe and the world come to us. Why? Because we are brilliant at it ... [Our music] reaches out, all inclusive, and embraces anyone and everyone. And that truly is what Britain is."[156]

In January 2018, it was reported that Sting had joined the board of advisors of an impact investing fund of JANA Partners LLC named JANA Impact Capital, aimed at serving environmental and social causes.[157] On 6 January 2018, JANA Partners, together with the California State Teachers' Retirement System issued a public letter imploring Apple Inc. to take a more responsible approach towards smartphone addiction among children. The letter cited several pieces of evidence that show that smartphone use by children increases the risk of their having mental health problems and worsens academic performance.[158]

Personal life

Sting married actress Frances Tomelty on 1 May 1976. They had two children: Joseph (b. 23 November 1976), and Fuschia Katherine "Kate" (b. 17 April 1982) Sumner. In 1980, Sting became a tax exile[159][160][161] in Galway, Ireland. In 1982, after the birth of his second child, he separated from Tomelty.[162] Tomelty and Sting divorced in 1984[163] following Sting's affair with actress Trudie Styler.[164] The split was controversial; as The Independent reported in 2006, Tomelty "just happened to be Trudie's best friend (Sting and Frances lived next door to Trudie in Bayswater, west London, for several years before the two of them became lovers)".[165]

Sting married Styler at Camden Registry Office on 20 August 1992, and the couple had their wedding blessed two days later in the twelfth-century parish church of St Andrew in Great Durnford, Wiltshire, south-west England.[162] Sting and Styler have four children, three of whom were born before their marriage: Brigitte Michael "Mickey" (b. 19 January 1984), Jake (b. 24 May 1985), Eliot Paulina "Coco" (b. 30 July 1990), and Giacomo Luke (b. 17 December 1995) Sumner. Coco is founder and lead singer of the group I Blame Coco. Giacomo Luke is the inspiration behind the name of Kentucky Derby-winning horse Giacomo.[166]

In April 2009, the Sunday Times Rich List estimated Sting's wealth at £175 million and ranked him the 322nd wealthiest person in Britain.[167] A decade later, Sting was estimated to have a fortune of £320 million in the 2019 Sunday Times Rich List, making him one of the ten wealthiest people in the British music industry.[168]

Both of Sting's parents died of cancer: his mother in 1986 and his father in 1987. He did not attend either funeral, in order not to draw media attention to them.[169]

In 1989, a western film written specifically for Sting was organized by his own and former Police video director Lol Creme. Sting's manager at the time Miles Copeland became involved, and the project was later passed to director Ridley Scott, but was never undertaken from there.[170]

In 1995, Sting gave evidence in court against his former accountant (Keith Moore), who had misappropriated £6 million of his money. Moore was jailed for six years.[171] Sting owns several homes worldwide, including Lake House and its sixty-acre estate near Salisbury, Wiltshire; a penthouse at 220 Central Park South in New York City; and the Villa Il Palagio estate in Figline Valdarno, Tuscany.[172] He owned a house in Highgate, 2 The Grove for a number of years, which had previously been the home of violinist Yehudi Menuhin.[173]

For much of his life, Sting's spare time interests and activities have revolved around mental and physical fitness. For many years, he ran five miles (8 km) a day and also performed aerobics. He participated in running races at Parliament Hill and charity runs (including the Race Against Time for Sport Aid in both 1986 and 1988). Around 1990, Danny Paradise introduced him to yoga and he began practising the Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga series, though he now practises Tantra and Jivamukti Yoga as well.[174] He wrote a foreword to Yoga Beyond Belief,[175] written by Ganga White in 2007. In 2008, he was reported to practise Maharishi Mahesh Yogi's Transcendental Meditation technique.[176] He also practises pilates regularly.[177]

Also a keen chess player, Sting played chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov in an exhibition game in 2000, along with four bandmates: Dominic Miller, Jason Rebello, Chris Botti and Russ Irwin. Kasparov beat all five simultaneously within fifty minutes.[178]

In 1969, Sting read the Gormenghast trilogy by Mervyn Peake and later bought the film rights. He named pets, a racehorse, his publishing company and one of his daughters (Fuschia, in the books actually Fuchsia) after characters from the books.[179]

Sting supports his hometown Premier League football club Newcastle United and in 2009 backed a supporters' campaign against the plan of owner Mike Ashley to sell off naming rights of the club's home stadium St James' Park.[180] He wrote a song in support of Newcastle, called "Black and White Army (Bringing The Pride Back Home)".[181]

In a 2011 interview in Time, Sting said that he was agnostic and that the certainties of religious faith were dangerous.[26]

In August 2014, Sting donated money to The Friends of Tynemouth Outdoor Pool to regenerate the 1920s lido at the southern end of Longsands Beach in Tynemouth, northeast England, a few miles from where he was born.[182]

Sting is vegetarian.[citation needed]

Awards and nominations

Discography

Studio albums

- The Dream of the Blue Turtles (1985)

- ...Nothing Like the Sun (1987)

- The Soul Cages (1991)

- Ten Summoner's Tales (1993)

- Mercury Falling (1996)

- Brand New Day (1999)

- Sacred Love (2003)

- Songs from the Labyrinth (2006)

- If on a Winter's Night... (2009)

- Symphonicities (2010)

- The Last Ship (2013)

- 57th & 9th (2016)

- 44/876 (2018) (with Shaggy)

- My Songs (2019)

- The Bridge (2021)[122][123]

Filmography

As actor

- Quadrophenia (1979) – The Ace Face, the King of the Mods, a.k.a. the Bell Boy in the film adaptation of the Who album.

- Radio On (1979) – Just Like Eddie

- The Great Rock 'n' Roll Swindle (1980) – Leader of the Blow Waves. The footage was cut but it later reappeared in the DVD version and in the documentary The Filth and the Fury (2000).

- Artemis 81 (1981) – The angel Helith (BBC TV film)

- Brimstone and Treacle (1982) – Martin Taylor, a drifter

- Dune (1984) – Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen

- Titus Groan (1984) – Steerpike (BBC Radio 4 broadcast based on the Mervyn Peake novel)

- Gormenghast (1984) – Steerpike (BBC Radio 4 broadcast based on the Mervyn Peake novel)

- Plenty (1985) – Mick, a black-marketeer

- The Bride (1985) – Baron Frankenstein

- Walking to New Orleans (1985) – Busker, singing Moon Over Bourbon Street.

- Julia and Julia (1987) – Daniel, a British gentleman

- The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988) – a "heroic officer"

- Stormy Monday (1988) – Finney, a nightclub owner

- The Grotesque (1995), a/k/a Gentlemen Don't Eat Poets and Grave Indiscretion – Fledge

- Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels (1998) – J.D., Eddie's father and owner of a bar.

- Kaamelott: The First Chapter (2021) – Horsa

As himself

- Urgh! A Music War (1982)

- Bring On the Night (1985)

- Saturday Night Live (1991) – host, various

- The Simpsons episode "Radio Bart" (1992)

- The Smell of Reeves and Mortimer Episode 5 (1995)

- The Larry Sanders Show episode "Where Is the Love?" (1996)

- Ally McBeal season four episode "Cloudy Skies, Chance of Parade" (2001)

- Everyone Stares: The Police Inside Out (2006)

- Studio 60 on Sunset Strip (2006)

- Vicar of Dibley Comic Relief special (2007)

- Bee Movie (2007)

- Little Britain USA (2008)

- Brüno (2009)

- Still Bill (2009)

- Do It Again (2010)

- Life's Too Short (2011)

- 2012: Time for Change (2011)

- Can't Stand Losing You: Surviving the Police (2012)

- The Michael J. Fox Show (2013) (singing "August Wind" from The Last Ship)

- 20 Feet from Stardom (2013)

- Zoolander 2 (2016)

- Have a Good Trip: Adventures in Psychedelics (2020)

- Only Murders in the Building (2021)

- The Book of Solutions (2023)

Theatre

Broadway and Tour credits

| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1982 | Rock 'N Roll! The First 5,000 Years | Writer: "Message in a Bottle" |

| 1989 | 3 Penny Opera | Role: Macheath |

| 2014 | The Last Ship | Music and lyrics Role: Jackie White |

| 2019 | ||

| 2020 |

Publications

- Broken Music. New York: Simon & Schuster. 2003. ISBN 0-7434-5081-7.

- Lyrics by – Sting. New York: Simon & Schuster. 2007. ISBN 978-1-84737-167-6.

See also

- List of artists who reached number one in the United States

- List of artists who reached number one on the U.S. Dance Club Songs chart

- List of Billboard number-one dance club songs

- List of music artists by net worth

- Lists of Billboard number-one singles

- Mononymous persons

Notes

- ^ About the 2016 Bataclan re-opening show, Sting stated: "In re-opening the Bataclan, we have two important tasks to reconcile. First, to remember and honour those who lost their lives in the attack a year ago, and second to celebrate the life and the music that this historic theatre represents. In doing so we hope to respect the memory as well as the life affirming spirit of those who fell. We shall not forget them."[106]

References

- ^ "Readers Poll: Ten Best Post-Band Solo Artists – 7. Sting". Rolling Stone. 2 May 2012.

- ^ Seely, Mike (1 September 2004). "The Ten Most Hated Men in Rock". The Riverfront Times. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ Collins, Robert (21 February 2014). "Review: Sting and Paul Simon serenade Vancouver". CTV Vancouver News.

- ^ Stephen Thomas Erlewine. Sting Biography. AllMusic. Retrieved 7 November 2010

- ^ "Sting releases new album My Songs today". Universal Music Canada. Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ^ a b Dartford, Katy (19 May 2023). "Sting awarded a Fellowship at the Ivor Novello Awards". euronews.com.

- ^ Vain, Madison (26 February 2017). "Oscars 2017: Sting performs 'The Empty Chair'". ew.com.

- ^ Smith, Connor (15 July 2024). "Sting added to Bourbon & Beyond lineup, replaces Neil Young". spectrumnews1.com.

- ^ "Tom Hanks, Sting, others saluted at Kennedy Center Honors". cbsnews.com. 7 December 2014.

- ^ a b Chow, Andrew R. (7 February 2017). "Sting and Wayne Shorter Win Polar Music Prize". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ^ Hutchinson, Ken (15 May 2015). Wallsend History Tour. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-4863-7.

- ^ Garrard, Aranda (2009). "Proud history and lively community; the region: Wallsend has grown out of its Roman and shipbuilding roots into a thriving community with plenty to offer buyers looking for a bargain". TheFreeLibrary.com. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ "Sting". The Biography Channel. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ Sting: The Secret Life of Gordon Sumner, Wensley Clarkson, Blake, 1996, p. 2

- ^ Sobel, Jon (27 October 2014). "Sting Thanks Queen Elizabeth for Touching Off the Ambition Leading to Last Night's Broadway Opening of His Musical 'The Last Ship'". Classicalite. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

On waving to the Queen as she rolled by in her Rolls Royce .. 10-year-old Gordon Sumner was "infected with the idea that I didn't want to be in this street, I didn't want to live in this house, I didn't want to end up in the shipyard—I wanted to be in that f*ing car."

- ^ "Sting: How I started writing songs again – TED Talk Subtitles and Transcript". TED Talk. 30 May 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

12:58.. big, black Rolls-Royce. Inside the Rolls-Royce is the Queen Mother. This is a big deal. So the procession is moving at a stately pace down my street, and as it approaches my house, I start to wave my flag vigorously, and there is the Queen Mother. I see her, and she seems to see me. She acknowledges me. She waves, and she smiles. And I wave my flag even more vigorously. We're having a moment, me and the Queen Mother. She's acknowledged me. And then she's gone. 13:50 Well, I wasn't cured of anything. It was the opposite, actually. I was infected. I was infected with an idea. I don't belong in this street. I don't want to live in that house. I don't want to end up in that shipyard. I want to be in that car. (Laughter) I want a bigger life. I want a life beyond this town. I want a life that's out of the ordinary. It's my right. It's my right as much as hers.

- ^ Sting (2003). Broken Music. Simon & Schuster.

- ^ Clarkson 1999, p. 17.

- ^ "Sting". Rolling Stone Australia. 2 July 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ "Notable Alumni". Northumbria University. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ Berryman, James (2000). A Sting in the tale. Mirage Publishing. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-902578-13-2. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ Cannell (2012), Kindle location 400–410.

- ^ Egan, Sean (8 August 2003). "The Police: Every Little Thing They Sang Was Magic". Goldmine. 29 (16): 14.

- ^ "Sting: A Renaissance man". CBS Sunday Morning. 22 September 2016. Archived from the original on 27 October 2021 – via YouTube.

I used to wear these yellow and black sweaters. They thought I looked like a wasp, and they'd joke. They called me 'Sting'. They thought it was hilarious. They kept calling me St... That became my name.

- ^ Periale, Elizabeth (4 October 2011). "Sting Turns 60 – How Did that Happen?". omg!. Archived from the original on 18 June 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ a b Luscombe, Belinda (21 November 2011). "10 Questions for Sting". Time. Archived from the original on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ Stern, Howard (5 February 2023). "Sting on How He Got His Nickname and Writing "Roxanne" (2016)". YouTube. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ "Brit Awards: The Police | BRITs Profile". Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ "The Police Chart history". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 August 2014

- ^ Billboard, 13 Dec 2003. p. 26

- ^ "'Last Play at Shea' documentary tells stadium's story". Newsday. New York. 20 April 2010. Archived from the original on 4 August 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ Fricke, David (22 January 2015). "The Police: A Fragile Truce". Rolling Stone.

- ^ "Reunited Police start world tour". BBC News. 30 May 2007. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. 31 May 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ "The Police: Timeline". Rock on the Net. Retrieved 16 October 2012

- ^ "The Greatest Artists of All Time". VH1/Stereogum. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ Flowers, Brandon. "The Police: 100 Greatest Artists of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ Lazell, Barry (1997). Indie Hits 1980–1989'. Cherry Red Books. p. 183. ISBN 0-9517206-9-4.

- ^ a b Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums. London: Guinness World Records Limited.

- ^ Analysis of this song, the H. Eisler-adaption The Secret Marriage and the J.S. Bach-quote in Whenever I Say Your Name in: Michael Custodis, chapter "Sting als Songwriter zwischen Prokofiev, Eisler, Bach und Dowland", in: Klassische Musik heute. Eine Spurensuche in der Rockmusik, Bielefeld transcript-Verlag 2009 ISBN 978-3-8376-1249-3

- ^ "Grammy Awards – Sting". National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 12 November 2014

- ^ Looking Back At Live Aid, 25 Years Later MTV. Retrieved 1 December 2011

- ^ "When Mark Knopfler and Sting Connected for 'Money for Nothing'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Live Aid – DVD Boxed Set AllMusic. Retrieved 15 September 2011

- ^ a b "Live Aid: The show that rocked the world". BBC News. 5 April 2000. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ^ 1985 MTV Video Music Awards MTV. Retrieved 4 December 2011

- ^ New York Times Film Reviews. The New York Times Company. 1988. p. 160.

- ^ Nothing Like the Sun Album Review Archived 3 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Rolling Stone. 29 December 2011

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Albums of the 80s." Rolling Stone. Special Issue 1990. Retrieved 19 November 2011

- ^ Barry Lazell (1989). Rock movers & shakers p.487. Billboard Publications, Inc., 1989

- ^ "Lyrics by Sting – to be published as a Dial Press Hardcover on October 23, 2007...". Sting.com. Retrieved 21 May 2017

- ^ Billboard: Ten Summoner's Tales AllMusic. Retrieved 1 December 2011

- ^ a b c d e f g Rock on the Net: Sting Rock on the Net. Retrieved 29 December 2011

- ^ a b "Brit Awards: Sting | BRITs Profile". Archived from the original on 15 January 2010. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ "Sting.com > Discography > SOUNDTRACK: The Emperor's New Groove". sting.com. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ 1997 Video Music Awards MTV. Retrieved 1 December 2011

- ^ "Billboard 6 September 1997". p.59. Billboard. Retrieved 7 January 2012

- ^ Sting sings at Winter Olympics BBC. Retrieved 29 December 2011

- ^ "The 47th Ivor Novello Awards" Archived 22 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The Ivors. Retrieved 31 December 2017

- ^ "No. 56963". The London Gazette (1st supplement). 14 June 2003. p. 9.

- ^ Analysis of the piece in: Michael Custodis, chapter Sting als Songwriter zwischen Prokofiev, Eisler, Bach und Dowland, in: Klassische Musik heute. Eine Spurensuche in der Rockmusik, Bielefeld transcript-Verlag 2009 ISBN 978-3-8376-1249-3

- ^ Lowry, Brian (29 February 2004). "Review: "The 76th Annual Academy Awards"". Variety. Archived from the original on 10 October 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ Culture (7 October 2011). "Annie Lennox: career timeline". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ a b "Live 8 – Sting". BBC. Retrieved 12 November 2014

- ^ "Guest Appearances – GREGG KOFI BROWN: Together As One". Sting.com. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ^ "Sting and Edin Karamazov: 'Songs from the Labyrinth'". Flyinginkpot.com. 22 February 1999. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ "Police tickets sell out in minutes" Archived 12 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine. TVNZ. One News.

- ^ "Stevie Wonder and Sting Inaugural Balls image" Archived 7 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone. Retrieved 12 November 2014

- ^ "Sting at Guitar Art Festival in Belgrade..." Sting.com. 10 February 2009. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009.

- ^ "Sting set to release new recording If on a Winter's Night..." (Press release). Sting.com. 17 June 2009. Archived from the original on 20 June 2009.

- ^ StingUs-team (6 October 2009). "Fan Reviews of 'If on a Winter's Night' New CD by Sting". Stingus.net. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ Anderson, Kyle (30 October 2009). "Tom Morello, John Legend, Sting brought out as special guests at Rock and Roll Hall of Fame 25th anniversary concert". MTV. Archived from the original on 31 December 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ Pareles, John (30 October 2009). "Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Concert: Set List". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ "The Police: inducted in 2003". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Pareles, John (11 March 2003). "Clash, Costello and Police Enter Rock Hall of Fame". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Barnes, Ed (13 April 2010). "Rocker Sting Stung by Controversy Over Secret Concert for Dictator's Daughter". Fox News. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ^ Powers, Ann (16 June 2010). "Symphonicity tour: A few thoughts on Sting and strings". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Mapes, Jillian (24 January 2013). "Sting Announces 2013 'Back To Bass' Tour, Includes 3 New England Dates". WZLX. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ "The 2011 TIME 100: Sting". Time. Archived from the original on 25 April 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ "Hive Five: Things Sting Saves". mtvhive.com. MTV. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ "Matthew Morrison (Glee)". HMV. Archived from the original on 18 June 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Sting and the Kalichstein-Laredo-Robinson Trio at 92nd Street Y". Goldstar Events. 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ "Sting and Brian Yorkey Embark on a New Musical, 'The Last Ship'". The New York Times. 1 September 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ "STING'S THE LAST SHIP – New Album From the 16-Time Grammy® Award Winner". Sting.com. 5 June 2013. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ^ "Sting's Visceral, Emotional 'The Last Ship' Arrives on Broadway". Rolling Stone. 3 November 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ^ Morgan, Scott C (11 October 2013). "Sting sails into Chicago to promote 'Last Ship'". Daily Herald. Chicago. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ Sullivan, Caroline (19 September 2013). "Sting: The Last Ship – review". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ Decurtis, Anthony (24 September 2013). "The Last Ship". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ "Sting to release first new original album in 10 years, 'The Last Ship'". Daily News. New York. 5 June 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ Graff, Gary (10 February 2014). "Paul Simon and Sting Q&A: Tour Mates on Shared Music DNA and Future 'Writing'". Billboard. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ "Sting & Paul Simon: On Stage Together – Second & Final Perth Show Added!". Sting.com. 10 July 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ "Sting & Paul Simon: On Stage Together – Final New Zealand Show Confirmed!". Sting.com. 25 August 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ "BELFAST DATE ADDED FOR 'PAUL SIMON & STING: ON STAGE TOGETHER' 2015 EUROPEAN TOUR". PaulSimon.com. 13 November 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ "Summer : 2015". Sting.com. February 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ "Stolen Car – Single par Mylène Farmer & Sting". iTunes Store. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ Presse, Prisma (15 September 2015). "Mylène Farmer: Un nouvel album au titre évocateur – Gala". Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ^ "iTunesCharts.net: 'Stolen Car' by Mylène Farmer & Sting (French Songs iTunes Chart)". itunescharts.net. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ^ "Sting, Peter Gabriel to headline Summerfest on July 10". 19 January 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ "Inside Sting's First Rock Album in Decades – How Prince's death, climate change inspired "impulsive" new LP". Rolling Stone. 18 July 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ "Sting announces new rock album 57th & 9th – "It's rockier than anything I've done in a while."". Consequence of Sound. 18 July 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ "Upcoming..." Sting.com. November 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ "Exclusive Sting.com Fan Club 57th & 9th Album Release Party Announced – November 9 at Irving Plaza in NYC!". Sting.com. 3 November 2016. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ "Sting '57th & 9th' Tour – Theatre, Club and Arena Tour Announced..." Sting.com. 14 November 2016. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ^ "Sting's Son to Join Him for Croatia Concert". Croatia Week. 10 April 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ Lutaud, Lena (4 November 2016), "Avec Sting, le monde entier va voir le Bataclan revivre!", Le Figaro, retrieved 5 November 2016

- ^ a b "Sting to Perform an Exclusive Concert in Paris for the Re-opening of the Bataclan on November 12". Sting.com. 4 November 2016. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ "Sting Will (Gently) Rock the Met in honour of Hudson River School great Thomas Cole | artnet News". artnet News. 5 January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ "BMI Announces Top Honors for its 67th Annual Pop Awards". BMI. Retrieved 9 June 2019

- ^ "Inside Sting and Shaggy's Unlikely, Caribbean-Inflected New Album (How the former Police bassist and Jamaican dancehall star teamed up for a wild, Caribbean-inflected LP)". Rolling Stone. 25 January 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ "The Queen celebrates her 92nd birthday in style with star-studded concert". Evening Standard. 21 April 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ "Sting's "Every Breath You Take" Is the Most Played Song on Radio [Video]". GuardianIv. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ "Hear Sting Rework Three Classics for New Album 'My Songs'". Rolling Stone. 28 March 2019.

- ^ "STING TEASES NEW ALBUM WITH 'RE-IMAGINED' VERSIONS OF HIS HITS". Ultimate Classic Rock. 10 January 2019.

- ^ "Sting is coming to Taos". Taos News. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ "Sting Launches Las Vegas Residency 'My Songs' At The Colosseum At Caesars Palace". PR Newswire. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ "Sting Announces Las Vegas Residency at Caesars Palace". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ "STING Fri 15 April 2022 – Thu 21 April 2022 Booking at The London Palladium SOLD OUT". LW Theatres. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ "All Saints Covers a Police Hit ... With None Other Than Sting: Listen". Billboard. Retrieved 5 May 2020

- ^ Huston-Crespo, Marysabel E (29 May 2020). "Ricky Martin sorprende con "Pausa", un EP en el que muestra su lado más vulnerable durante la cuarentena" (in Spanish). CNN en Español. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "The 50 Greatest Bassists of All Time". au.rollingstone.com. 2 July 2020.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Duets – Sting". AllMusic. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Sting has 'no truck' with his rock peers who oppose vaccines: 'I'm old enough to remember polio'". Los Angeles Times. 25 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Sting Readying Album of New Songs, Called "The Bridge," for November Release with Single, "If It's Love"". Showbiz411.com. 25 August 2021.

- ^ Esguerra, Tyler (26 October 2021). "Riot's Arcane soundtrack features Imagine Dragons, Sting, Denzel Curry, Pusha T, Bea Miller, and more". Dot Esports. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ "Arcane: League of Legends – Every Song, Ranked". ScreenRant. 3 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ "The DeanBeat: The Game Awards and the game industry are back". VentureBeat. 10 December 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ Marten, Todd (10 December 2021). "Game Awards, with audience in the millions, must now be bold and address industry issues". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ "Swedish House Mafia officially release new song 'Redlight'". Los Angeles Times. 3 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Koc, Cagan (10 February 2022). "Sting Is the Latest Rock Star to Sell His Song Catalog to Universal". Bloomberg.

- ^ "The World's 10 Highest-Paid Entertainers". Forbes. Archived from the original on 17 February 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ "Wall Street Journal. "Microsoft Hosted Sting Performance in Davos on Night Before Announcing Layoffs By Tom Dotan and Sam Schechner". Wsj.com. 19 January 2023. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ "Microsoft execs held ritzy party with rocker Sting before massive layoffs". The Seattle Times. 19 January 2023. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ "REVOLVER". The Irish Times. 10 October 2006. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ "Sting TV Interview On NBC Today Show about Amnesty concerts". 22 April 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2011 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b "How Amnesty International Rocked the World: The Inside Story" Archived 27 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone. Retrieved 12 November 2014

- ^ "Looking Back At Live Aid, 25 Years Later". MTV. Retrieved 28 October 2016

- ^ "30 facts for 30 years – The truth about 'Spitting Image'". ITV. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- ^ "Sting TV Interview on NBC Today Show about Amnesty concerts". 22 April 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2011 – via YouTube.

- ^ Turner, Terence (1993). "The Role of Indigenous Peoples in the Environmental Crisis: The Example of the Kayapo of the Brazilian Amazon". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 36 (3): 526–545. doi:10.1353/pbm.1993.0027. ISSN 0031-5982. S2CID 71983607.

- ^ M. Kaplan (1994). "A new species of frog of the genus Hyla from the Cordillera Oriental in northern Colombia with comments on the taxonomy of Hyla minuta". Journal of Herpetology. 28 (1). Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles: 79–87. doi:10.2307/1564684. JSTOR 1564684.

- ^ "Chilean Women's Resistance in the Arpillera Movement". coha.org. 19 June 2008. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ "The Courage of Conscience Award". peaceabbey.org. The Peace Abbey. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ Carman, John (22 September 2001). "Musicians, actors honor heroes, raise money for attack victims". San Francisco Chronicle. p. A1.

- ^ "Sting Concert Raises 4 m for Tsunami". The Sydney Morning Herald. 11 February 2005. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ "The original and the best: 30 years of Leeuwin Estate concerts". Perth Now. 17 February 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ^ "Willie Nelson stages Tsunami gig". BBC News. 10 January 2005. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ "The Police, West, Mayer Close Out Live Earth New York". Billboard. Retrieved 12 November 2914

- ^ "Sting, Matthews, Mayer gamer for Tibet than Beijing". E!. 22 July 2008. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008.

- ^ Karger, Dave (22 January 2010). "'Hope for Haiti Now': The telethon's 10 best performances". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ Richards, Chris (26 April 2010). "Earth Day Climate Rally features music, speeches and an assist from Mother Nature". The Washington Post. p. C.1. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ "Elton John AIDS Foundation patrons". Elton John AIDS Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ "Dame Judi Dench and Sting head drug rethink call". BBC News. 2 June 2011.

- ^ "NBC Hurricane Sandy Telethon Raises 23 Million". Rolling Stone. 5 November 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ Kaupang Jørgensen, Karina (23 September 2015). "Sting til TV-aksjonen" (in Norwegian). NRK. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ "Celebrities' open letter to Scotland – full text and list of signatories". The Guardian. London. 7 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ "UK music stars rail against Brexit in open letter to Theresa May". The Guardian. 6 October 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ "Wall Street Fighters, Do-Gooders—And Sting—Converge in New Jana Fund". The Wall Street Journal. 7 January 2018.

- ^ "Open Letter from JANA Partners and CalSTRS to Apple Inc". Think Differently About Kids. 6 January 2018. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ McMahon, Gary (August 2008). "The Returns of the Prodigal Tax Exile". Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ^ "Sting | Music's Top Twelve Tax Exiles". Comcast.net. Archived from the original on 20 January 2010. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ GQ, June 1985, Interview with Fred Schruers

- ^ a b "Sting on Love and Wife Trudie Styler: She Rocks Me". People. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ "Interview: The thing about Sting…". The Guardian. 24 September 2011.

- ^ Higginbotham, Adam (3 August 2002). "Interview: Trudie Styler". The Guardian.

- ^ "Trudie Styler: The truth about Trudie". The Independent. 4 August 2006. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ^ "Every Little Horse He Names is Magic (Or Just About)". The New York Times. 4 November 2010. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ "Search the Sunday Times Rich List 2009". The Times. London. 26 April 2009. Archived from the original on 11 May 2009. Retrieved 29 April 2009.

- ^ Mee, Emily (14 May 2019). "Who made the Sunday Times Rich List this year?". Sky News. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ Sutcliffe, Phil (October 1996). "Interview Date: October 1996". Q. Archived from the original on 5 April 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- ^ Lit 14: Sting, Ridley Scott, Others: Gil Farrington On the Devil’s Plain (September 1989), Internet Archive, 9 September 2024, retrieved 20 January 2025

- ^ "Sting's adviser jailed for pounds 6m theft from star". The Independent. 18 October 1995. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ Lippe-Mcgraw, Jordi (31 July 2019). "Sting Buys $65.7 Million Penthouse on Manhattan's Billionaires' Row". Architectural Digest.

- ^ Richardson, John (1983). Highgate: Its history since the Fifteenth Century. Eyre and Spottiswoode. ISBN 0-9503656-4-5.

- ^ "Sting and Yoga". YogaEdge. 1 June 2011. Archived from the original on 16 January 2015. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ "Yoga Beyond Belief". White Lotus Foundation. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ Shankar, Jay (6 February 2008). "Maharishi Mahesh Yogi". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- ^ "Sting Daily Routine". 16 January 2021.

- ^ Manning, Kara (30 June 2000). "Sting Battles Chess King Kasparov in Times Square". MTV. Archived from the original on 1 October 2004. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ "Police man's Peake – 'Weird and wonderful' is how superstar Sting describes the novels of Mervyn Peake..." Radio Times. December 1984. Archived from the original on 13 November 2006.

- ^ Mitchell, Terry (12 November 2009). "Newcastle United fans campaign backed by Sting". The Football Fan Census. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ "Celeb Toon fans join protest against Ashley". Metro. UK. 25 April 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ Sharma, Sonia (3 August 2013). "Geordie star Sting's cash gift to help save Tynemouth Outdoor Pool". Evening Chronicle.

Bibliography

- Berryman, James (2005). Sting and I. John Blake. ISBN 1-84454-107-X.

- Berryman, James (2000). A Sting in the Tale. Mirage Publishing. ISBN 1-902578-13-9.

- Cannell, Paul (2012). Fuckin' Hell It's Paul Cannell. Poodle Publishing. ISBN 9781475020793.

- Carr, Paul (2017). Sting: From Northern Skies to Fields of Gold. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78023-813-5.

- Clarkson, Wensley (1999) [1996]. Sting: The Secret Life of Gordon Sumner. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 1-56025-226-X.

- Gable, Christopher (2009). The Words and Music of Sting. Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-99360-3.

- Marienberg, Evyatar (2021). Sting and Religion: The Catholic-Shaped Imagination of a Rock Icon. Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books / Wipf & Stock. ISBN 978-1-7252-7226-2.

- Sandford, Christopher (1998). Sting: Demolition Man. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-0603-1.

- Sting (2003). Broken Music: A Memoir. New York: Dial Press. ISBN 0-385-33678-0.

- West, Aaron J. (2015). Sting and the Police: Walking in Their Footsteps. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-8490-8.

External links

- Sting

- Sting at AllMusic

- Sting discography at Discogs

- Sting at IMDb

- Sting at the Internet Broadway Database

- Sting discography at MusicBrainz

- Sting's Commencement Address (1994) to the Berklee College of Music

- Sting radio interview about John Dowland songs, from NPR Performance Today, 6 March 2007

- Sting Archived 20 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine live in Minsk (video) on the Belarus official website Archived 2 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine