Steppe Route

The Steppe Route was an ancient overland route through the Eurasian Steppe that was an active precursor of the Silk Road. Silk and horses were traded as key commodities; secondary trade included furs, weapons, musical instruments, precious stones (turquoise, lapis lazuli, agate, nephrite) and jewels. This route extended for approximately 10,000 km (6,200 mi).[1] Trans-Eurasian trade through the Steppe Route preceded the conventional date for the origins of the Silk Road by at least two millennia.[2]

Geography

The Steppe Route centered on the North Asian steppes and connected eastern Europe to northeastern China.[3] The Eurasian Steppe has a wide and plane topography, and a unique ecosystem.[4] The Steppe Route extended from the mouth of the Danube River to the Pacific Ocean. It was bounded on the north by the forests of Russia and Siberia. There was no clear southern boundary, although the southern semi-deserts and deserts impeded travel. The principal characteristic of the steppe landscape is its continental climate and the deficiency of moisture, which creates unstable conditions for farming. The steppe is interrupted at three points: the Ural mountains, the Altai mountains which gradually turn into the Sayan mountains in the east, and the Greater Khingan range; these divided the steppe into four segments that could be crossed by horsemen. The altitude of some mountainous barriers, such as the Altai Mountains, with elevations up to 4,000 metres (13,000 ft), originally kept some regions self-contained.

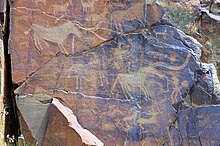

The vast territory stretching alongside the Steppe Route is diversified and includes dry steppe, desert, mountains, oases, lakes, rivers and river deltas, lowland steppe, mountain steppe, and forest steppe regions.[5] Its wildlife was a permanent source of inspiration for artists and early craftsmanship. Hippocrates reflected on the impact of climatic changes, on subsistence, and advanced the idea of their influence on the organisation of human communities, as an explanation to populations migration. The demographic pressure on farming areas adjacent to the Steppe Route probably led the more fragile groups located at the periphery of those farming areas to migrate in search of better living conditions. Since rich pastures were not always available, it fostered the transition to a nomadic existence. This lifestyle fostered a military culture necessary to protect herds and to conquer new territories. The specific geography of the steppe created an ecosystem capable of diffusing critical development features, including the spread of modern humans, animal domestication and animal husbandry, spoke-wheeled chariot and cavalry warfare, early metal production (copper) and trade, Indo-European languages, and the political rise of nomadic states.

Communities

In the absence of discovered written language records from early Eurasian nomads, it is difficult to determine how they referred to themselves, and the various earliest cultures along the Steppe Road are mostly identified by distinctive burial arrangements and delicate artifacts.[6] The quality of the artifacts are a testimony of the degree of sophistication of the nomadic preliterate culture and craftmanship which tends to undermine notions that nomadic communities were necessarily less developed than sedentary ones. The nomadic practices of herding and simultaneously farming, in which horse-riding warfare practised by an elite played a central role[7] spread in the area from around 1000 BCE.[8] The later steppe nomads typically were organized communities, rotating their homes a few times a year between summer and winter pastures and being recognized and expected by other neighboring communities. These groups seem to have interacted often, and they also traded and preyed upon settled communities.[9]

A common view is that the early communities of the Eurasian steppe were clustered but not necessarily closely related ethnically. On the one hand, each population may have had its own history. On the other hand, communities maintained close contacts with both their neighbors and with those further distant. French historian Fernand Braudel saw the presence of pastoral nomads as a disruptive force often interrupting periods of slow historical processes, allowing for rapid change and cultural oscillation.

Newly studied archaeological sites such as Berel[10] in Kazakhstan, an elite burial ground of the Pazyryk culture located near the borders with Russia, Mongolia, and China at the junction of the Altai and Tarbagatai mountains along the Kara-Kaba River, showed that much work still needs to be performed to better understand the communities bordering this intercultural transportation route and to assess unexcavated sites in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan. The work confirmed that the semi-nomadic groups of the late fourth and early third centuries BCE, known to Herodotus as the Arimaspians, were not only breeding horses for trade. They were also metallurgists, builders, potters, jewelers, woodcarvers and painters who left a durable influence at the confluent of the Eastern and Western world.

History

Upper paleolithic

By the end of the Pliocene, tectonic activity had created the major mountain ranges and lowlands, including the Aral and Caspian Sea basins and the Sarykamysh depression; the primitive Syr Darya, Zeravshan, Amu Darya, Uzboy, Murghab, Tedzhen, Atrek, and Gorgan river systems were formed.[11] Cyclical climatic changes during the Pleistocene and Holocene epochs finally produced a warmer and less dry climate in the greater part of western Asia that led to the present-day configuration and ecology of the region. The first modern humans to migrate to Asia and Europe were hunter gatherers; they probably started to move from Africa at the time of the Green Sahara episode. Fossils excavated in Mount Carmel, Israel in 2002, show that Homo sapiens arrived earlier than previously thought at the gate of the Steppe Route 194,000–177,000 years ago and possibly interbred with Neanderthals who inhabited some parts of Eurasia.[12] The overall migration pattern of these populations is still unclear. The hunter-gatherers were slowly replaced around 9000 BCE by new immigrants from the Near East who had greater subsistence capacities due to their knowledge of primitive farming.

The dominant position occupied by nomadic communities in the steppe ecological niche was a result of their nomadic military and technical superiority and is thought to have originated in the North Caucasian steppes as early as the 8th millennium BCE. The post-glacial period was marked by a gradual rise of temperatures, which peaked in the 5th and 4th millennia BCE. These more hospitable conditions provided humans with grasslands and more stable food supplies and resulted in a sharp increase in their numbers. The regular collection of wild cereals led to the empirical breeding and selection of cereals (wheat, barley) that could be cultivated. It also led to the domestication of animals (donkeys, asses, horses, sheep, goats) for stockbreeding.[13] Although the quality and quantity of artifacts varies from site to site, the general impression is that the development of craftsmanship contributed to more stable settlements and a more precise definition of routes connecting certain communities with each other. The Aurignacian culture spread through Siberia, and as a testimony of its presence, an Aurignacian Venus figurine was found near Irkutsk, on the Upper Angara River.[14] Traces of the Magdalenian culture were also identified in Manchuria, Siberia and Hebei. Pastoralism introduced a major leap in social development and prepared the necessary base for the creation of ancient semi-nomadic states along the Eurasian Steppe Route.[13]

The analysis of carbon and nitrogen isotopes in skeletal collagen of these same human remains has helped to classify their dietary background and to characterize the economy of the steppe communities. Strontium isotope analysis has helped to identify faunal and human movements between various regions. Oxygen isotope analysis is applied to reconstruct early drinking habits and climatic change's impact on populations.[15] The combination of these factors has aimed at reconstructing a more precise picture of the living conditions of the time. The analysis of 1,500 mitochondrial genome lineages helped to date the arrival in different regions of Europe of hunter-gatherers who later developed a knowledge of farming. It was found that in central and southwest Europe, these could mainly be traced to the Neolithic. In the central and eastern Mediterranean, the arrival of the first human migrants can be dated to the much earlier Late Pleistocene period.[16]

Neolithic

The early acquaintance with a food-producing economy in the Pontic-Caspian Steppe is assigned to this period. The transition from a food-gathering to a food-producing economy through farming and stock-keeping led to profound social and cultural changes. Hunting and river fishing likely continued to play a significant role in subsistence, especially in the forest steppe areas. The transition to animal husbandry played a critical role in the history of the rise of human society, and it was a significant contributor to the "Neolithic revolution". Simultaneously, a new way of life emerged with the construction of more comfortable settlements for plant and animal domestication, craft activities (resulting in the wide use of ornaments) and burial practices, including the erection of the first burial mounds in the Chalcolithic or Eneolithic period (the transition between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age).

The lands of the Inner Eurasian steppe were occupied, possibly since the fourth millennium BCE, by nomadic communities, namely those of the Proto-Indo-Iranian speaking Andronovo Culture, practicing extensive forms of horse pastoralism, moving from place to places.[4] This ensured that the pastoralists' contacts and influence would extend over large areas. The earliest evidence for riding comes from the Sredny Stog communities of eastern Ukraine and from south Russia with the domestication of the Bactrian camel[17] dating to c. 4000 BCE. This two*humped heavy load carrier is one of the most adaptive animals in the world, capable of withstanding temperatures from 40 °C to -30 °C. In eastern Eurasia, agriculture was likely started by Indo-European communities (Tocharians) established in the Tarim Basin of northwestern China) around 4000 BCE.[18] In western Eurasia, the revolutionary introduction of writing, dated to the same period, apparently originated to serve accounting needs but developed with the Sumerian concern to leave messages for the afterlife.[19][20] In Inner China, which represented about half of the territory of the modern Chinese state (i.e., excluding Manchuria, Mongolia, Xinjiang and the Qinghai-Tibet plateau,[21] there have been discoveries of tortoise-shell carvings of Jiahu symbols dating back to c. 6200-6600 BCE. For now, they seem to qualify as symbols rather than as evidence of systematic writing.[22] Writing and accounting likely started independently in various areas of Eurasia, including the Mediterranean Basin and Mesopotamia, but they appear to have spread relatively rapidly along the Steppe Route.

Bronze Age

The transition period to the Bronze Age shows varying patterns in the different geographical regions of the Steppe Route. However, numerous craft activities involved the manufacture of ornaments, instrumental goods and domestic commodities. As early as the 6th-5th millennium BCE (Vinča culture, situated in what is now Serbia), the Pontic-Caspian steppe can be traced as the homeland of copper production, which then spread throughout the entire steppe zone over the following two millennia.[23] At the beginning of the fourth millennium, copper technology was introduced in the Altai region by steppe herders. The Bronze Age was marked by an abrupt cooling of the climate, which at the turn of the 3rd-2nd millennium B.C. gave way to a new temperature rise more favourable to farming and herding. The dual use of a prehistoric cavalry and metal weapons probably laid the framework of a much more militarized and possibly more hostile environment, triggering the migration of the most peaceful - or weakest - Homo sapiens populations to more remote parts of the Steppe route.[24]

Advanced craftsmanship such as metal-smelting and pottery production (painted vessels and terracotta sculpture) are found side by side with large areas covered with wastes from the production of ornaments made of semiprecious stones (lapis-lazuli, turquoise, spinel, quartz.[25] Economic prosperity led to an exceptional richness of artistic expression that was to be found in the smaller forms, particularly in painted ceramics, small carved objects, ornaments inspired by wildlife, and funerary gifts. It was also conducive to a more complex organization of society.[23]

The first Bronze Age of Korea began with the expansion of the Seima-Turbino metallurgy phenomenon (1500–900 BCE). Scytho-Saka Culture and the Lute-shaped Dagger Culture existed in Manchuria. Upper Xiajiadian culture formed and interacted with that of the Karasuk and early Scytho-Saka periods in 1100–700 BCE. During this time, Karasuk-style bronzeware spread not only to the Upper Xiajadian, but also to North Korea, the Liaoning area, and the far eastern region of Russia (Primorisky). During this time, the Lute-shaped Dagger Culture was clearly present in Manchuria and the northern part of the Korean peninsula.[26] The trading patterns on the Steppe Route show that the East Asian silk did not only come from China. The Neolithic remains (4000-3000 BCE) of the Goguryeo kingdom (Korea) showed earthenware with silkworm and mulberry leaf patterns and small carvings in rock of silkworms. The Records of the Three Kingdoms [27] noted that both confederacies of Byeonhan and Jinhan (later known as Silla and Gaya kingdoms in Korea), “had many mulberry trees and silkworms”, indicating that the silk produced on the Korean Peninsula was known in other countries from ancient times. In the late 3rd millennium BCE, military-oriented stockbreeding communities settled in eastern Central Asia (Sayan-Altai, Mongolia). The Nephrite (Jade) Road materialized; the mineral was quarried in Khotan and Yarkand and sold to China.[17] Communities were even more mobile on the Steppe Route after the introduction of carts.[28]

The end of the Bronze Age on the Eurasian Steppe route shows that production and a new economic organisation led to the accumulation of riches by a number of families and new economic interactions.[29] Their male leaders then became warlords, clashing and striking alliances for the control of the best pastures or migrating to start what might become new states.

Dynastic ages

By 2000 BCE the network of Steppe Routes exchanges started to transition to the Silk Road. By the middle of this millennium, the “steppe route” cultures were well-established. Slow-moving groups following a heavy chariot with four solid wheels led by hunters and fishermen were gradually replaced or enslaved by herdsmen from the steppes and semi-deserts. Nomads rode small horses and knew how to fight from horseback, primarily with a bow that was the distinctive weapon from the steppe and sometimes even with a sword or a saber when the rider was more affluent.[9] Members of these mobile, energetic and resourceful communities used light war-chariots with wheels having a diameter up to one meter with 10 spokes and drawn by horses,[30] The pattern spread in many different directions and strengthened an already-robust system of vigorous and widespread exchanges within and sometimes beyond the inner Eurasian steppes. These early systems of exchange depended largely on the role of intertwined pastoralist communities.[31] The result was a complex pattern of migratory movements, transformations and cultural interactions alongside the steppe route. In the 2nd millennium BCE there were major shifts of population over a wide area of Central Asia, and the whole picture of ethnocultural development changed.

According to the writings of Roman historian Dio Cassius, Romans saw high-quality silk for the first time in 53 BCE, in the form of Parthian banners unfurled before the Roman defeat at the battle of Carrhae.[2]

Various artifacts, including glassware, excavated from tombs in the Korean kingdom of Silla were similar to those found in the Mediterranean part of the Roman Empire, showing that exchange did take place between the two extremities of the steppe road.[32] It is estimated that the travel time for commercial goods from Constantinople (Istanbul) in Turkey to reach Gyeongju in Korea would not have exceeded six months. This Roman glass and other artifacts were passed through Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and Manchuria to Gyeongju. The traded goods show that trade through the Steppe Route was still active in 600 CE.[33] The interrelation of China with the Steppe Route may have contributed to the brilliant progress of Chinese civilization in the Yin (Shang 商) dynasty, based on the appearance of three major innovations probably imported from the Eurasian steppe's western communities: wheeled transport, the horse, and metallurgy.[17] The influences that had traveled along the Steppe Route from the Mediterranean to the Korean Peninsula can be seen in similar techniques, styles, cultures, religions, and even disease patterns.

See also

Gallery

- Steppe of East Ayagoz region, Kazakhstan.

- Mongolian-Manchurian grassland region of the eastern Eurasian Steppe in Mongolia.

References

- ^ "The Horses of the Steppe: The Mongolian Horse and the Blood-Sweating Stallions | Silk Road in Rare Books". dsr.nii.ac.jp. Retrieved 2017-02-22.

- ^ a b Christian, David (2000-03-01). "Silk Roads or Steppe Roads? The Silk Roads in World History". Journal of World History. 11 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1353/jwh.2000.0004. ISSN 1527-8050. S2CID 18008906.

- ^ Miho Museum News (Shiga, Japan), Volume 23, March 2009 (22 February 2017). "Eurasian winds toward Silla". Archived from the original on 2016-04-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Gan, Fuxi (2009-01-01). Ancient Glass Research Along the Silk Road. World Scientific. p. 44. ISBN 9789812833570.

- ^ Davis-Kimball, Jeannine; Bashilov, V. A.; I͡Ablonskiĭ, Leonid Teodorovich (1995-01-01). Nomads of the Eurasian Steppes in the Early Iron Age. Zinat Press. ISBN 9781885979001.

- ^ Bryant, Edwin; Bryant, Edwin Francis (2001-09-06). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 205. ISBN 9780195137774.

- ^ Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW) at New York University (NYU), News Release (28 February 2012). "Nomads and Networks: The Ancient Art and Culture of Kazakhstan".

- ^ Jean-Paul Desroches, chief curator of the Musée National des Arts Asiatiques Guimet, Paris, France (3 February 2001). "L'Asie des steppes d'Alexandre le Grand à Gengis Khån, page 4" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hildinger, Erik (1997). Warriors Of The Steppe: Military History Of Central Asia, 500 Bc To 1700 Ad. Da Capo Press. p. 6. ISBN 0306810654.

- ^ Gerling, Claudia (2015-07-01). Prehistoric Mobility and Diet in the West Eurasian Steppes 3500 to 300 BC: An Isotopic Approach. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 71–72. ISBN 9783110311211.

- ^ Harris, David R. (2011-09-01). Origins of Agriculture in Western Central Asia: An Environmental-Archaeological Study. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 19–21. ISBN 978-1934536513.

- ^ Callaway, Ewen (2018-01-25). "Israeli fossils are the oldest modern humans ever found outside of Africa". Nature. 554 (7690): 15–16. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-01261-5. PMID 29388957.

- ^ a b Sariadini, Viktor. History of Civilization of Central Asia, Volume I, Food-producing and other neolithic communities in Khorasan and Transoxonia: Eastern Iran Soviet Central Asia and Afghanistan (PDF). UNESCO Publishing. pp. 105, 125–126. ISBN 978-92-3-102719-2.

- ^ Grousset, René (1970-01-01). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Rutgers University Press. pp. 3. ISBN 9780813513041.

steppe route.

- ^ Gerling, Claudia (2015-07-01). Prehistoric Mobility and Diet in the West Eurasian Steppes 3500 to 300 BC: An Isotopic Approach. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 4. ISBN 9783110311211.

- ^ Pereira, Joana B., with Pr Richards and Dr Luisa Pereira of the Institute of Molecular Pathology and Immunology, University of Porto, Reconciling evidence from ancient and contemporary genomes: a major source for the European Neolithic within Mediterranean Europe, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2017). doi:10.1098/rspb.2016.1976

- ^ a b c Kuzmina, E. E. (2008-01-01). The Prehistory of the Silk Road. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 70, 88. ISBN 978-0812240412.

- ^ "An Overview of the Silk Road: Time, Space and Themes | Silk Road in Rare Books". dsr.nii.ac.jp. Retrieved 2017-02-26.

- ^ Denise., Schmandt-Besserat (1992-01-01). From counting to cuneiform. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292707832. OCLC 225899662.

- ^ Schmandt-Besserat, Denise (25 January 2014). "The evolution of writing (abstract)" (PDF).

- ^ Thorp, Robert L. (2006-01-01). China in the Early Bronze Age: Shang Civilization. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 2–10. ISBN 0812239105.

- ^ "BBC NEWS | Science/Nature | 'Earliest writing' found in China". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-02-26.

- ^ a b Cunliffe, Barry (2015-09-24). By Steppe, Desert, and Ocean: The Birth of Eurasia. OUP Oxford. pp. 107–108. ISBN 9780191003356.

- ^ Chernykh, Evgenij Nikolaevich (September 2008). "Formation of the Eurasian Steppe Belt of Stockbreeding cultures: viewed from the prism of archeometallurgy and radiocarbon dating". Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia (Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia ed.). Elsevier: 36–53, Volume 35, Issue 3. doi:10.1016/j.aeae.2008.11.003.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ M. Tosi, S. Malek Shahmirzadi and M. A. Joyenda (1992). History of civilization of central Asia, Volume 1, The bronze age in Iran and Afghanistan (PDF). Unesco Publishing. p. 198. ISBN 9789231027192.

- ^ Kang, In-Uk (2020). "Archaeological Perspectives on the Early Relations of the Korean Peninsula with the Eurasian Steppe" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers: 34p.

- ^ Chen Shou [280s or 290s]. Pei Songzhi, ed. (1977). Record of the Three Kingdoms, 三國志. Taipei: Dingwen Printing.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Chernykh, E.N. (2008). "Formation of the Eurasian 'steppe belt' of stockbreeding cultures: viewed through the prism of archaeometallurgy and radiocarbon dating". Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia. 35 (3). Archaeology Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia 35 (3), Elsevier: 36–53. doi:10.1016/j.aeae.2008.11.003.

- ^ Yuri, Rassamakin. "Levine M., Rassamakin Yu., Kislenko A. and Tatarintseva N. (with an introduction by C.Renfrew), 1999. Late Prehistoric Exploitation of the Eurasian Steppe. McDonald Institute Monographs, University of Cambridge, 216 pp.: pp. 59-182".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Masson, V.M. (1992). History of civilization of Central Asia, Volume 1, The decline of the Bronze age and the movement of the tribes (PDF). Unesco Publishing. pp. 326–330. ISBN 92-3-102719-0.

- ^ "Stark, S., Rubinson, K., Samashev, Z., et al., eds.: Nomads and Networks: The Ancient Art and Culture of Kazakhstan. (Hardcover)". press.princeton.edu. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- ^ "Republic of Korea | SILK ROAD". en.unesco.org. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ Park, Chun Soo (2018). "Roman Glass, not through China's central region, but through eastern Eurasia". The Dong-a Ilbo.