Great Purge

| Great Purge | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Bolshevik Party purges | |

People of Vinnytsia searching through the exhumed victims of the Vinnytsia massacre, 1943 | |

| Location | Soviet Union, Xinjiang, Mongolian People's Republic |

| Date | Main phase: 19 August 1936 – 17 November 1938 (2 years, 2 months, 4 weeks and 1 day) |

| Target | Political opponents, Trotskyists, Red Army leadership, kulaks, religious activists and leaders |

Attack type | |

| Deaths | 681,692 executions and 116,000 deaths in the Gulag system (official figures)[1]

700,000 to 1.2 million (estimated)[1] [2][3] |

| Perpetrators | Joseph Stalin, the NKVD (Genrikh Yagoda, Nikolai Yezhov, Lavrentiy Beria, Ivan Serov and others), Vyacheslav Molotov, Andrey Vyshinsky, Lazar Kaganovich, Kliment Voroshilov, Robert Eikhe and others |

| Motive | Elimination of political opponents,[4] consolidation of power,[5] fear of counterrevolution,[6] fear of party infiltration[7] |

| Mass repression in the Soviet Union |

|---|

| Economic repression |

| Political repression |

| Ideological repression |

| Ethnic repression |

| Part of a series on the |

| History of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Communism |

|---|

|

|

|

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (Russian: Большой террор, romanized: Bol'shoy terror), also known as the Year of '37 (37-й год, Tridtsat' sed'moy god) and the Yezhovshchina (Ежовщина [(j)ɪˈʐofɕːɪnə], lit. 'period of Yezhov'), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. It sought to consolidate Joseph Stalin's power over the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and aimed at removing the remaining influence of Leon Trotsky within the Soviet Union.[8] The term great purge was popularized by the historian Robert Conquest in his 1968 book The Great Terror, whose title was an allusion to the French Revolution's Reign of Terror (sometimes referred to as "les épurations").[9]

The purges were largely conducted by the NKVD (People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs), which functioned as the interior ministry and secret police of the USSR. Starting in 1936, the NKVD under chief Genrikh Yagoda began the removal of the central party leadership, Old Bolsheviks, government officials, and regional party bosses.[10] Soviet politicians who opposed or criticized Stalin were removed from office and imprisoned or executed by the NKVD. Eventually, the purges were expanded to the Red Army and military high command, which had a disastrous effect on the military.[11][12] The campaigns also affected many other categories of society: the intelligentsia, wealthy peasants—especially those lending out money or wealth (kulaks)—and professionals.[13] As the scope of the purge widened, the omnipresent suspicion of saboteurs and counter-revolutionaries, known collectively as wreckers, began affecting civilian life. The purge reached its peak between September 1936 and August 1938, when the NKVD was under chief Nikolai Yezhov, hence the name Yezhovshchina. The campaigns were carried out according to the general line of the party, often by direct orders of the politburo, headed by Stalin.[14] Hundreds of thousands of people were accused of various political crimes (espionage, wrecking, sabotage, anti-Soviet agitation, conspiracies to prepare uprisings and coups, and more). They were executed by shooting, or sent to the Gulag labor camps. The NKVD targeted certain ethnic minorities with particular force, such as the Volga Germans or Soviet citizens of Polish origin, who were subjected to forced deportation and extreme repression. Throughout the purge, the NKVD sought to strengthen control over civilians through fear, and frequently used imprisonment, torture, violent interrogation, and executions during its mass operations.[15]

In 1938, Stalin reversed his stance on the purges, criticized the NKVD for carrying out mass executions, and oversaw the execution of NKVD chiefs Genrikh Yagoda and Nikolai Yezhov. Scholars estimate the death toll for the Great Purge (1936–1938) to be roughly 700,000–1.2 million.[16][17][18][19] Despite the end of the Great Purge, the widespread surveillance and atmosphere of mistrust continued for decades. Similar purges took place in Mongolia and Xinjiang. While the Soviet government desired to put Trotsky on trial during the purge, his exile prevented this. Trotsky survived the purge, though he would be assassinated in 1940 by the NKVD in Mexico, on the orders of Stalin.[20][21]

Background

Following the death of Vladimir Lenin in 1924, a power vacuum opened in the Communist Party, the ruling party in the Soviet Union (USSR). Various established figures in Lenin's government attempted to succeed him. By 1928, Joseph Stalin, the party's General Secretary, had triumphed over his opponents and gained control of the party.[22] Initially, Stalin's leadership was widely accepted; his main political adversary, Trotsky, was forced into exile in 1929, and Stalin's doctrine of "socialism in one country" became enshrined party policy. However, in the early 1930s, party officials began to lose faith in his leadership, largely due to the human cost of the first five-year plan and the collectivization of agriculture, notably including the Holodomor famine in Ukraine.

From 1930 onwards, the Party and police officials feared the "social disorder" caused by the upheavals of forced collectivization of peasants and the resulting famine of 1930–1933, as well as the massive and uncontrolled migration of millions of peasants into cities. The threat of war heightened Stalin's and generally Soviet perception of marginal and politically suspect populations as the potential source of an uprising in case of invasion. Stalin began to plan for the preventive elimination of such potential recruits for a mythical "fifth column of wreckers, terrorists, and spies."[23][24][25]

The term "purge" in Soviet political slang was an abbreviation of the expression purge of the Party ranks. In 1933, for example, the Party expelled some 400,000 people. But from 1936 until 1953, the term changed its meaning, because being expelled from the Party came to mean almost certain arrest, imprisonment, and often execution.

The political purge was primarily an effort by Stalin to eliminate challenge from past and potential opposition groups, including the left and right wings led by Leon Trotsky and Nikolai Bukharin, respectively. Following the Civil War and reconstruction of the Soviet economy in the late 1920s, veteran Bolsheviks no longer thought necessary the "temporary" wartime dictatorship, which had passed from Lenin to Stalin. Stalin's opponents inside the Communist Party chided him as undemocratic and lax on bureaucratic corruption.[26]

This opposition to current leadership may have accumulated substantial support among the working class by attacking the privileges and luxuries the state offered to its high-paid elite. The Ryutin affair seemed to vindicate Stalin's suspicions. Ryutin was working with the even larger secret Opposition Bloc in which Leon Trotsky and Grigory Zinoviev participated,[27][28] and which later led to both of their deaths. Stalin enforced a ban on party factions and demoted those party members who had opposed him, effectively ending democratic centralism.

In the new form of Party organization, the Politburo, and Stalin in particular, were the sole dispensers of ideology. This required the elimination of all Marxists with different views, especially those among the prestigious "old guard" of revolutionaries. As the purges began, the government (through the NKVD) shot Bolshevik heroes, including Mikhail Tukhachevsky and Béla Kun, as well as the majority of Lenin's Politburo, for disagreements in policy. The NKVD attacked the supporters, friends, and family of these "heretical" Marxists, whether they lived in Russia or not. The NKVD nearly annihilated Trotsky's family before killing him in Mexico; the NKVD agent Ramón Mercader was part of an assassination task force put together by Special Agent Pavel Sudoplatov, under the personal orders of Stalin.[29]

By 1934, several of Stalin's rivals, such as Trotsky, began calling for Stalin's removal and attempted to break his control over the party.[30] In this atmosphere of doubt and suspicion, the popular high-ranking official Sergei Kirov was assassinated. The assassination, in December 1934, led to an investigation that revealed a network of party members supposedly working against Stalin, including several of Stalin's rivals.[31] Many of those arrested after Kirov's murder, high-ranking party officials among them, also confessed plans to kill Stalin themselves, albeit often under duress.[32] The validity of these confessions is debated by historians, but there is consensus that Kirov's death was the flashpoint at which Stalin decided to take action and begin the purges.[33][34] Some later historians came to believe that Stalin arranged the murder, or at least that there was sufficient evidence to reach such a conclusion.[35] Kirov was a staunch Stalin loyalist, but Stalin may have viewed him as a potential rival because of his emerging popularity among the moderates. The 1934 Party Congress elected Kirov to the central committee with only three votes against, the fewest of any candidate, while Stalin received 292 votes against. After Kirov's assassination, the NKVD charged the ever-growing group of former oppositionists with Kirov's murder as well as a growing list of other offenses, including treason, terrorism, sabotage, and espionage.

Another justification for the purge was to remove any possible "fifth column" in case of a war. Vyacheslav Molotov and Lazar Kaganovich, participants in the repression as members of the Politburo, maintained this justification throughout the purge; they each signed many death lists.[36] Stalin believed war was imminent, threatened both by an explicitly hostile Germany and an expansionist Japan. The Soviet press portrayed the country as threatened from within by fascist spies.[35]

From the October Revolution[37] onward,[38] Lenin had used repression against perceived and legitimate enemies of the Bolsheviks as a systematic method of instilling fear and facilitating control over the population in a campaign called the Red Terror. As the Russian Civil War drew to a close, this campaign was relaxed although the secret police did remain active. From 1924 to 1928, the mass repression—including incarceration in the Gulag system—dropped significantly.[39]

By 1929, Stalin had defeated his political opponents and gained full control over the party. He organized a committee to begin the process of industrialization of the Soviet Union. Backlash against industrialization and the collectivization of agriculture escalated, which prompted Stalin to increase police presence in rural areas. Soviet authorities increased repression against the kulaks (i.e., wealthy peasants that owned farmland) in a policy called dekulakization. The kulaks responded by destroying crop yields and other acts of sabotage against the Soviet government.[40] The food shortage led to a mass famine across the USSR and slowed the Five Year Plan.

A distinctive feature of the Great Purge was that, for the first time, members of the ruling party were included on a massive scale as victims of the repression. In addition to ordinary citizens, prominent members of the Communist Party were also targets for the purges.[41] The purge of the Party was accompanied by the purge of the whole society. Soviet historians organize the Great Purge into three corresponding trials. The following events are used for the demarcation of the period:

- 1936, the first Moscow trial.

- 1937, introduction of NKVD troikas for implementation of "revolutionary justice."

- 1937, passage of Article 58-14 about "counter-revolutionary sabotage."

- 1937, the second Moscow trial

- 1937, the military purge.[42]

- 1938, the third Moscow trial.

Moscow trials

First and second Moscow trials

Between 1936 and 1938, three very large Moscow trials of former senior Communist Party leaders were held, in which they were accused of conspiring with fascist and capitalist powers to assassinate Stalin and other Soviet leaders, dismember the Soviet Union and restore capitalism. These trials were highly publicized and extensively covered by the outside world, which was mesmerized by the spectacle of Lenin's closest associates confessing to most outrageous crimes and begging for death sentences:[original research?]

- The first trial was of 16 members of the so-called "Trotskyite-Kamenevite-Zinovievite-Leftist-Counter-Revolutionary Bloc," held in August 1936,[43] at which the chief defendants were Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev, two of the most prominent former party leaders, who had indeed been members of a Conspiratorial Bloc that opposed Stalin, although its activities were exaggerated.[27] Among other accusations, they were incriminated with the assassination of Kirov and plotting to kill Stalin. After confessing to the charges, all were sentenced to death and executed.[44]

- The second trial in January 1937 involved 17 lesser figures known as the "anti-Soviet Trotskyite-centre" which included Karl Radek, Yuri Piatakov and Grigory Sokolnikov, and were accused of plotting with Trotsky, who was said to be conspiring with Germany. Thirteen of the defendants were eventually executed by shooting and the rest received sentences in labor camps where they soon died.[45]

- There was also a secret trial before a military tribunal of a group of Red Army commanders, including Mikhail Tukhachevsky, in June 1937.[46]

It is now known that the confessions were given only after great psychological pressure and torture had been applied to the defendants.[47] From the accounts of former OGPU officer Alexander Orlov and others, the methods used to extract the confessions are known: such tortures as repeated beatings, simulated drownings, making prisoners stand or go without sleep for days on end, and threats to arrest and execute the prisoners' families. For example, Kamenev's teenage son was arrested and charged with terrorism. After months of such interrogation, the defendants were driven to despair and exhaustion.[48]

Zinoviev and Kamenev demanded, as a condition for "confessing", a direct guarantee from the Politburo that their lives and that of their families and followers would be spared. This offer was accepted, but when they were taken to the alleged Politburo meeting, only Stalin, Kliment Voroshilov, and Yezhov were present. Stalin claimed that they were the "commission" authorized by the Politburo and gave assurances that death sentences would not be carried out. After the trial, Stalin not only broke his promise to spare the defendants, he had most of their relatives arrested and shot.[49]

Dewey Commission

In May 1937, the Commission of Inquiry into the Charges Made against Leon Trotsky in the Moscow Trials, commonly known as the Dewey Commission, was set up in the United States by supporters of Trotsky, to establish the truth about the trials. The commission was headed by the noted American philosopher and educator John Dewey. Although the hearings were obviously conducted with a view to proving Trotsky's innocence, they brought to light evidence which established that some of the specific charges made at the trials could not be true.[50]

For example, Georgy Pyatakov testified that he had flown to Oslo in December 1935 to "receive terrorist instructions" from Trotsky. The Dewey Commission established that no such flight had taken place.[51] Another defendant, Ivan Smirnov, confessed to taking part in the assassination of Sergei Kirov in December 1934, at a time when he had already been in prison for a year.

The Dewey Commission later published its findings in a 422-page book titled Not Guilty. Its conclusions asserted the innocence of all those condemned in the Moscow Trials. In its summary, the commission wrote

Independent of extrinsic evidence, the Commission finds:

- That the conduct of the Moscow Trials was such as to convince any unprejudiced person that no attempt was made to ascertain the truth.

- That while confessions are necessarily entitled to the most serious consideration, the confessions themselves contain such inherent improbabilities as to convince the Commission that they do not represent the truth, irrespective of any means used to obtain them.

- That Trotsky never instructed any of the accused or witnesses in the Moscow trials to enter into agreements with foreign powers against the Soviet Union [and] that Trotsky never recommended, plotted, or attempted the restoration of capitalism in the USSR.

The commission concluded: "We therefore find the Moscow Trials to be frame-ups."[52]

Implication of the Rightists

In the second trial, Karl Radek testified that there was a "third organization separate from the cadres which had passed through [Trotsky's] school,"[53] as well as "semi-Trotskyites, quarter-Trotskyites, one-eighth-Trotskyites, people who helped us, not knowing of the terrorist organization but sympathizing with us, people who from liberalism, from a Fronde against the Party, gave us this help."[54]

By the "third organization," he meant the last remaining former opposition group called the Rightists, led by Bukharin, whom he implicated by saying:

I feel guilty of one thing more: even after admitting my guilt and exposing the organisation, I stubbornly refused to give evidence about Bukharin. I knew that Bukharin's situation was just as hopeless as my own, because our guilt, if not juridically, then in essence, was the same. But we are close friends, and intellectual friendship is stronger than other friendships. I knew that Bukharin was in the same state of upheaval as myself. That is why I did not want to deliver him bound hand and foot to the People's Commissariat of Home Affairs. Just as in relation to our other cadres, I wanted Bukharin himself to lay down his arms.[53]

Third Moscow trial

The third and final trial, in March 1938, known as the Trial of the Twenty-One, is the most famous of the Soviet show trials, because of persons involved and the scope of charges which tied together all loose threads from earlier trials. Meant to be the culmination of previous trials,[neutrality is disputed] it included 21 defendants alleged to belong to the "Bloc of Rightists and Trotskyites", supposedly led by Nikolai Bukharin, the former chairman of the Communist International, former premier Alexei Rykov, Christian Rakovsky, Nikolai Krestinsky, and Genrikh Yagoda, recently disgraced head of the NKVD.[27]

Although an Opposition Bloc led by Trotsky and with zinovievites really existed, Pierre Broué asserts that Bukharin was not involved.[27] Differently from Broué, one of his former allies,[55] Jules Humbert-Droz, said in his memoirs that Bukharin told him that he formed a secret bloc with Zinoviev and Kamenev in order to remove Stalin from leadership.[56]

The fact that Yagoda was one of the accused showed the speed at which the purges were consuming their own. It was now alleged that Bukharin and others sought to assassinate Lenin and Stalin from 1918, murder Maxim Gorky by poison, partition the USSR and hand its territories to Germany, Japan, and Great Britain, and other charges.[citation needed]

Even previously sympathetic observers who had accepted the earlier trials found it more difficult to accept these new allegations as they became ever more absurd, and the purge expanded to include almost every living Old Bolshevik leader except Stalin and Kalinin.[citation needed] No other crime of the Stalin years so captivated Western intellectuals as the trial and execution of Bukharin, who was a Marxist theorist of international standing.[57] For some prominent communists such as Bertram Wolfe, Jay Lovestone, Arthur Koestler, and Heinrich Brandler, the Bukharin trial marked their final break with communism, and even turned the first three into fervent anti-communists eventually.[58][59] To them, Bukharin's confession symbolized the depredations of communism, which not only destroyed its sons but also conscripted them in self-destruction and individual abnegation.[57]

Bukharin's confession

On the first day of trial, Krestinsky caused a sensation when he repudiated his written confession and pleaded not guilty to all the charges. However, he changed his plea the next day after "special measures", which dislocated his left shoulder among other things.[60]

Anastas Mikoyan and Vyacheslav Molotov later claimed that Bukharin was never tortured, but it is now known[neutrality is disputed] that his interrogators were given the order "beating permitted", and were under great pressure to extract confession out of the "star" defendant. Bukharin initially held out for three months, but threats to his young wife and infant son, combined with "methods of physical influence" wore him down. But when he read his confession amended and corrected personally by Stalin, he withdrew his whole confession. The examination started all over again, with a double team of interrogators.[61]

Bukharin's confession in particular became subject of much debate among Western observers, inspiring Koestler's acclaimed novel Darkness at Noon and philosophical essay by Maurice Merleau-Ponty in Humanism and Terror. His confessions were somewhat different from others in that while he pleaded guilty to "sum total of crimes", he denied knowledge when it came to specific crimes. Some astute observers noted that he would allow only what was in written confession and refuse to go any further.[citation needed]

The result was a curious mix of fulsome confessions (of being a "degenerate fascist" working for "restoration of capitalism") and subtle criticisms of the trial. One observer noted that after disproving several charges against him, Bukharin "proceeded to demolish or rather showed he could very easily demolish the whole case."[62] He continued by saying that "the confession of the accused is not essential. The confession of the accused is a medieval principle of jurisprudence" in a trial that was based solely on confessions. He finished his last plea with the words:[63]

[T]he monstrousness of my crime is immeasurable especially in the new stage of struggle of the U.S.S.R. May this trial be the last severe lesson, and may the great might of the U.S.S.R. become clear to all.

Romain Rolland and others wrote to Stalin seeking clemency for Bukharin, but all the leading defendants were executed except Rakovsky and two others (who were killed in NKVD prisoner massacres in 1941). Despite the promise to spare his family, Bukharin's wife, Anna Larina, was sent to a labor camp, but she survived to see her husband posthumously rehabilitated a half-century later by the Soviet state under Mikhail Gorbachev in 1988.[citation needed]

"Ex-kulaks" and other "anti-Soviet elements"

On 2 July 1937, in a top secret order to regional Party and NKVD chiefs Stalin instructed them to produce the estimated number of "kulaks" and "criminals" in their districts. These individuals were to be arrested and executed, or sent to the gulag camps. The party chiefs complied and produced these lists within days, with figures which roughly corresponded to the individuals who were already under secret police surveillance.[25]

On 30 July 1937, the NKVD Order No. 00447 was issued, directed against "ex-kulaks" and other "anti-Soviet elements" (such as former officials of the Tsarist regime, former members of political parties other than the communist party, etc.). They were to be executed or sent to Gulag prison camps extrajudicially, under the decisions of NKVD troikas.

The following categories appear to have been on index-cards, catalogues of suspects assembled over the years by the NKVD and were systematically tracked down: "ex-kulaks" previously deported to "special settlements" in inhospitable parts of the country (Siberia, the Urals, Kazakhstan, and the Far North), former tsarist civil servants, former officers of the White Army, participants in peasant rebellions, members of the clergy, persons deprived of voting rights, former members of non-Bolshevik parties, ordinary criminals, like thieves, known to the police and various other "socially harmful elements".[64]

However, a large number of people were arrested at random in sweeps, on the basis of denunciations or because they were related to, were friends with or knew people already arrested. Engineers, peasants, railwaymen, and other types of workers were arrested during the "Kulak Operation" based on the fact that they worked for or near important strategic sites and factories where work accidents had occurred due to "frantic rhythms and plans". During this period the NKVD reopened these cases and relabeled them as "sabotage" or "wrecking."[65]

The Orthodox clergy, including active parishioners, was nearly annihilated: 85% of the 35,000 members of the clergy were arrested. Particularly vulnerable to repression were also the so-called "special settlers" (spetzpereselentsy) who were under permanent police surveillance and constituted a huge pool of potential "enemies" to draw on. At least 100,000 of them were arrested in the course of the Great Terror.[66]

Common criminals such as thieves, "violators of the passport regime", etc. were also dealt with in a summary way. In Moscow, for example, nearly one third of the 20,765 persons executed on the Butovo firing range were charged with a non-political criminal offence.[66]

To carry out the mass arrests, the 25,000 officers of the State Security personnel of NKVD were complemented with units of ordinary police, and Komsomol (Young Communist League) and civilian Communist Party members. Seeking to fulfill the quotas, the police rounded up people in markets and train stations, with the purpose of arresting "social outcasts".[25] Local units of the NKVD, in order to meet their "casework minimums" and force confessions out of arrestees worked long uninterrupted shifts during which they interrogated, tortured and beat the prisoners. In many cases those arrested were forced to sign blank pages which were later filled in with a fabricated confession by the interrogators.[25]

After the interrogations the files were submitted to NKVD troikas, which pronounced the verdicts in the absence of the accused. During a half-day-long session a troika went through several hundred cases, delivering either a death sentence or a sentence to the Gulag labor camps. Death sentences were immediately enforceable. The executions were carried out at night, either in prisons or in secluded areas run by the NKVD and located as a rule on the outskirts of major cities.[64]

The "Kulak Operation" was the largest single campaign of repression in 1937–38, with 669,929 people arrested and 376,202 executed, more than half the total of known executions.[67]

Campaigns targeting nationalities

A series of mass operations of the NKVD was carried out from 1937 through 1938 targeting specific nationalities within the Soviet Union, on the order of Nikolai Yezhov.

The Polish Operation of the NKVD was the largest of this kind.[68] The Polish operation claimed the largest number of the NKVD victims: 143,810 arrests and 111,091 executions according to records. Snyder estimates that at least eighty-five thousand of them were ethnic Poles.[68] The remainder were 'suspected' of being Polish, without further inquiry.[69]

Red Army Air Forces, fell victim to the "Latvian Operation" in 1938

Poles comprised 12.5% of those who were killed during the Great Terror, while comprising only 0.4% of the population. Overall, national minorities targeted in these campaigns composed 36%[70] of the victims of the Great Purge, despite being only 1.6%[70] of the Soviet Union's population. 74%[70] of ethnic minorities arrested during the Great Purge were executed while those sentenced during the Kulak Operation had only a 50% chance of being executed,[70] (though this may have been due to the Gulag camp's lack of space in the late stages of the Purge rather than deliberate discrimination in sentencing).[70]

The wives and children of those arrested and executed were dealt with by the NKVD Order No. 00486. The women were sentenced to forced labour for 5 or 10 years.[71] Their minor children were put in orphanages. All possessions were confiscated. Extended families were purposely left with nothing to live on, which usually sealed their fate as well, affecting up to 200,000–250,000 people of Polish background depending on the size of their families.[71] National operations of the NKVD were conducted on a quota system using album procedure. The officials were mandated to arrest and execute a specific number of so-called "counter-revolutionaries", compiled by administration using various statistics but also telephone books with names sounding non-Russian.[citation needed]

The Polish Operation of the NKVD served as a model for a series of similar NKVD secret decrees targeting a number of the Soviet Union's diaspora nationalities: the Finnish, Latvian, Estonian, Bulgarian, Afghan, Iranian, Greek, and Chinese.[72] Of the operations against national minorities, it was the largest one, second only to the "Kulak Operation" in terms of the number of victims. According to Timothy Snyder, ethnic Poles constituted the largest group of victims in the Great Terror, comprising less than 0.5% of the country's population but comprising 12.5% of those executed.[73]

Timothy Snyder attributes 300,000 deaths during the Great Purge to "national terror" including ethnic minorities and Ukrainian "kulaks" who had survived dekulakization and the Holodomor famine that had been used to kill millions in the early 1930s.[74] Lev Kopelev wrote "In Ukraine 1937 began in 1933", referring to the earlier Soviet political repressions in Ukraine.[75]: 418 There was also deadly persecution of Ukrainian cultural elites, who are referred to as the Executed Renaissance. Statistics of Ukraine's Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicate that about 200,000 victims of the Great Purge were Ukrainians.[76]

Concerning diaspora minorities, the vast majority of whom were Soviet citizens and whose ancestors had resided for decades and sometimes centuries in the Soviet Union and Russian Empire, "this designation absolutized their cross-border ethnicities as the only salient aspect of their identity, sufficient proof of their disloyalty and sufficient justification for their arrest and execution" (Martin, 2001: 338).[77] Some scholars have called the national operations of the NKVD genocidal.[78][79][80][81] Norman Naimark called Stalin's policy towards Poles in the 1930s "genocidal".[81] However, he does not consider the Great Purge entirely genocidal because it also targeted political opponents.[81]

Some scholars, however, focus on the security dilemma in the border areas suggesting the need to secure the ethnic integrity of Soviet space vis-à-vis neighboring capitalistic enemy states.[72] They stress the role of international relations and believe that representatives of these minorities were killed not because of their ethnicity, but because of their possible relations to countries hostile to the USSR and fear of disloyalty in the case of an invasion.[72] Nevertheless, little proof exists to suggest that Russia's and Stalin's alleged prejudices played a central causal role in the Great Purge.[82]

Purge of the army

The purge of the Red Army and Military Maritime Fleet removed three of five marshals (then equivalent to four-star generals), 13 of 15 army commanders (then equivalent to three-star generals),[83] eight of nine admirals (the purge fell heavily on the Navy, who were suspected of exploiting their opportunities for foreign contacts),[84] 50 of 57 army corps commanders, 154 out of 186 division commanders, 16 of 16 army commissars, and 25 of 28 army corps commissars.[85]

At first, it was thought 25–50% of Red Army officers had been purged; the true figure is now known to be in the area of 3.7–7.7%. This discrepancy was the result of a systematic underestimation of the true size of the Red Army officer corps, and it was overlooked that most of those purged were merely expelled from the Party. Thirty percent of officers purged in 1937–1939 were allowed to return to service.[86]

The purge of the army was claimed to be supported by German-forged documents (alleged correspondence between Marshal Tukhachevsky and members of the German high command).[87] This claim is unsupported by facts, as by the time the documents were supposedly created, two of Tukhachevsky's group were already imprisoned, and by the time the document was said to reach Stalin, the purging process was already underway. Furthermore, actual evidence introduced at trial was obtained from forced confessions.[88]

The purge had a significant effect on German decision making in World War II: many German generals opposed an Invasion of Russia, but Hitler disagreed, arguing that the Red Army was less effective after its intellectual leadership had been eliminated in the purge.[89]

Wider purge

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Russian Trotskyist historian Vadim Rogovin argued that Stalin had destroyed thousands of foreign communists capable of leading socialist change in their respective countries. He referenced 600 active Bulgarian communists that perished in his prison camps along with the thousands of German communists that were handed over from Stalin to the Gestapo after the signing of the German-Soviet Pact. Rogovin also noted that sixteen members of the Central committee of the Communist Party of Germany became victims of Stalinist terror. Repressive measures were also enforced upon the Hungarian, Yugoslav and other Polish Communist parties.[90]

According to historian Eric D. Weitz, 60% of German exiles in the Soviet Union were liquidated during the Stalinist terror, and a higher proportion of the KPD Politburo membership had died in the Soviet Union than had died in Nazi Germany. Weitz also noted that hundreds of German citizens, the majority of whom were Communists, were handed over to the Gestapo from Stalin's administration.[91] Many Jewish figures such as Alexander Weissberg-Cybulski and Fritz Houtermans were arrested in 1937 by the NKVD and turned over to the German Gestapo.[92] Joseph Berger-Barzilai, co-founder of the Communist Party of Palestine, spent twenty five years in Stalin's prisons and concentrations camps after the purges in 1937.[93][94]

External purges were also conducted in Spain, in which the NKVD oversaw purges of anti-Stalinist elements in the Spanish Republican forces including Trotskyist and anarchist factions.[95] Notable cases involved the execution of Andreu Nin, Spanish POUM and former government minister, Jose Robles, a left-wing academic and translator along with many members of the POUM faction.[96][97][98]

Out of six members of the original Politburo during the October Revolution who lived until the Great Purge, Stalin himself was the only one who remained in the Soviet Union, alive.[37] Four of the other five were executed; the fifth, Leon Trotsky, had been forced into exile outside the Soviet Union in 1929, but was assassinated in Mexico by Soviet agent Ramón Mercader in 1940. Of the seven members elected to the Politburo between the October Revolution and Lenin's death in 1924, four were executed, one (Tomsky) committed suicide, and two (Molotov and Kalinin) lived.[citation needed]

A series of documents discovered in the Central Committee archives in 1992 by Vladimir Bukovsky demonstrate that there were limits for arrests and executions as for all other activities in the planned economy.[citation needed]

The victims were convicted in absentia and in camera by extrajudicial organs—the NKVD troikas sentenced indigenous "enemies" under NKVD Order No. 00447 and the two-man dvoiki (NKVD Commissar Nikolai Yezhov and Main State Prosecutor Andrey Vyshinsky, or their deputies) those arrested along national lines.[citation needed][99]

The victims were executed at night, either in prisons, in the cellars of NKVD headquarters, or in a secluded area, usually a forest. The NKVD officers shot prisoners in the head using pistols.[66][100] Other methods of dispatching victims were used on an experimental basis. In Moscow, the use of gas vans to kill the victims during their transportation to the Butovo firing range has been documented.[101]

Intelligentsia

Those who perished during the Great Purge include:

- Theoretical physicist Matvei Bronstein and pioneer of quantum gravity[103] was arrested, accused of fictional "terroristic" activity and shot in 1938.[104][105]

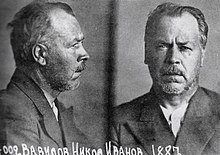

- Nikolai Vavilov was a prominent Russian geneticist and botanist that made several contributions to agricultural science such as the law of homologous series in variation and centres of origins of cultivated plants.[106] He was removed from his formal positions in 1935 and perished in prison in 1943 following his conflicts with Trofim Lysenko. The controversy would also contribute to a wider decline in genetic research in the Soviet Union.[107]

- Experimental physicist Lev Shubnikov considered the "Soviet founding father of Soviet low-temperature physics"[108] He was known for the discovery of the Shubnikov–de Haas effect and type-II superconductivity.[108] He also one of the first to discover antiferromagnetism.[109] Shubnikov was executed in 1937.[110]

- Soviet economist Nikolai Kondratiev was a proponent for the New Economic Policy and developed the business cycle theory known as Kondratiev waves.[111] Kondratiev was executed in 1938.[112]

- Valerian Obolensky, was a Soviet economist, chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the National Economy[113] and Professor of the Agricultural Academy[114][115] in Moscow but was eventually executed on fabricated charges in 1938.

- Isaak Rubin, Soviet economist and ranked among the most influential contributors to the classical Marxist tradition. He is noted for his seminal work, Essays on Marx's Theory of Value. Rubin was arrested and executed in 1937.[116][117]

- Vladimir Milyutin, Russian economist, politician and statistician, supporter of a socialist coalition government in 1917 and worker's control.[118][119] Perished under Stalin's purges in 1937.[120]

- Astronomer Boris Numerov, founder of the Computing Institute in 1919 and was noted for his specialism in applied celestial mechanics before the Second World War. He was executed in 1941.[121]

- Soviet engineer and inventor Ivan Kleymyonov who among the key founders of Soviet rocketry, chief of the Gas Dynamics Laboratory.[122] Kleymyonov was executed in 1938.

- Soviet astrophysicist and astronomer, Boris Gerasimovich who was director of the Pulkovo Observatory. Gerasimovich was arrested along with 13 other astronomers and was personally executed in 1938.[123]

- Soviet engineer and chairman of the Supreme Council of the National Economy, Pyotr Bogdanov, who oversaw Soviet construction projects and nationalization of the chemical industry. Bogdanov was executed in 1939.[124]

- Soviet military theorist and general, Alexander Svechin, was a leading thinker in the field during the 1920s and noted for his seminal work, Strategy, before he was purged in 1938.[125][126][127]

- Poet Aleksei Gastev, director of Central Institute of Labour and pioneering theorist of scientific management of labour in the Soviet Union.[128][129] His son, Yuri Gastev became a prominent Soviet cybernetician, emigre and eventual political dissident.[130][131]

- Jewish German mathematician Fritz Noether had fled persecution from Nazi Germany in 1934. He was also the sibling of prominent mathematician Emmy Noether who made various contributions to abstract algebra. He had contributed to the Herglotz–Noether theorem in special relativity. Albert Einstein had futilely pleaded for his case prior to his eventual execution due to accusations of working as a German spy.[132][133][134]

- Poet Osip Mandelstam was arrested for reciting his famous anti-Stalin poem Stalin Epigram to his circle of friends in 1934. After intervention by Nikolai Bukharin and Boris Pasternak (Stalin jotted down in Bukharin's letter with feigned[according to whom?] indignation: "Who gave them the right to arrest Mandelstam?"), Stalin instructed NKVD to "isolate but preserve" him, and Mandelstam was "merely" exiled to Cherdyn for three years, but this proved to be a temporary reprieve. In May 1938, he was arrested again for "counter-revolutionary activities".[135] On 2 August 1938, Mandelstam was sentenced to five years in correction camps and died on 27 December 1938 at a transit camp near Vladivostok.[136] Pasternak himself was nearly purged, but Stalin is said to have crossed Pasternak's name off the list, saying "Don't touch this cloud dweller."[137]

- Writer Isaac Babel was arrested in May 1939, and according to his confession paper (which contained a blood stain) he "confessed" to being a member of a Trotskyist organization and being recruited by French writer André Malraux to spy for France. In the final interrogation, he retracted his confession and wrote letters to the prosecutor's office stating that he had implicated innocent people, but to no avail. Babel was tried before an NKVD troika and convicted of simultaneously spying for the French, Austrians and Trotsky, as well as "membership in a terrorist organization". On 27 January 1940, he was shot in Butyrka prison.[138]

- Nikolai Sukhanov, chronicler of the Russian Revolution of 1917, agrarian economist, revolutionary intellectual and editor of the opposition paper.[139] Initially, arrested during the Menshevik Trials in 1931, arrested again in 1937 for alleged espionage before he was ultimately executed in 1940.[140]

- Writer Boris Pilnyak was arrested on 28 October 1937 for counter-revolutionary activities, spying and terrorism. One report alleged that "he held secret meetings with [André] Gide, and supplied him with information about the situation in the USSR. There is no doubt that Gide used this information in his book attacking the USSR." Pilnyak was tried on 21 April 1938. In the proceeding that lasted 15 minutes, he was condemned to death and executed shortly afterward.[138]

- Theatre director Vsevolod Meyerhold was arrested in 1939 and shot in February 1940 for "spying" for Japanese and British intelligence. His wife, the actress Zinaida Raikh, was murdered in her apartment.[141] In a letter to Molotov dated 13 January 1940, Meyerhold wrote:

The investigators began to use force on me, a sick 65-year-old man. I was made to lie face down and beaten on the soles of my feet and my spine with a rubber strap ... For the next few days, when those parts of my legs were covered with extensive internal hemorrhaging, they again beat the red-blue-and-yellow bruises with the strap and the pain was so intense that it felt as if boiling water was being poured on these sensitive areas. I howled and wept from the pain. I incriminated myself in the hope that by telling them lies I could end the ordeal. When I lay down on the cot and fell asleep, after 18 hours of interrogation, in order to go back in an hour's time for more, I was woken up by my own groaning and because I was jerking about like a patient in the last stages of typhoid fever.[138]

- Georgian poet Titsian Tabidze was arrested on 10 October 1937 on a charge of treason and was tortured in prison. In a bitter humor, he named only the 18th-century Georgian poet Besiki as his accomplice in anti-Soviet activities.[142] He was executed on 16 December 1937.

- Tabidze's lifelong friend and fellow poet, Paolo Iashvili, having earlier been forced to denounce several of his associates as the enemies of the people, shot himself with a hunting gun in the building of the Writers' Union.[143] He witnessed and was even forced to participate in public trials that ousted many of his associates from the Writers' Union, effectively condemning them to death. When Lavrentiy Beria, chief of the Soviet security and secret police apparatus under Stalin and subsequently head of the NKVD, further pressured Iashvili with the alternatives of denouncing Tabidze or being arrested and tortured by the NKVD, Iashvili killed himself.[142]

- In early 1937, poet Pavel Nikolayevich Vasiliev is said to have defended Nikolai Bukharin as "a man of the highest nobility and the conscience of peasant Russia" at the time of his denunciation at the Pyatakov Trial (Second Moscow Trial) and damned other writers then signing the routine condemnations as "pornographic scrawls on the margins of Russian literature". He was promptly shot on 16 July 1937.[144]

- Jan Sten, philosopher and deputy head of the Marx-Engels Institute, was Stalin's private tutor when Stalin was trying hard to study Hegel's dialectic. (Stalin received lessons twice a week from 1925 to 1928, but he found it difficult to master even some of the basic ideas. Stalin developed enduring hostility toward German idealistic philosophy, which he called "the aristocratic reaction to the French Revolution".) Sten eventually became a member of an underground opposition group, and this group later joined the Bloc of Soviet Oppositions which was led by Leon Trotsky.[27] In 1937, Sten was seized on the direct order of Stalin, who declared him one of the chiefs of "Menshevizing idealists". On 19 June 1937, Sten was put to death in Lefortovo prison.[145]

- David Riazanov, Soviet historian and founder of the Marx-Engels Institute. He had been an old associate of Leon Trotsky.[146] Arrested and put to death in 1938.[147]

- Poet Nikolai Klyuev was arrested in 1933 for contradicting Soviet ideology. He was shot in October 1937.

- Russian linguist Nikolai Durnovo, born into the Durnovo noble family, was executed on 27 October 1937. He created a classification of Russian dialects that served as a base for modern scientific linguistic nomenclature.[148]

- Mari poet and playwright Sergei Chavain was executed in Yoshkar-Ola on 11 November 1937. The State prize of Mari El is named after Chavain.

- Ukrainian theater and movie director Les Kurbas, considered by many to be the most important Ukrainian theater director of the 20th century, was shot on 3 November 1937.

- Russian writer and explorer Maximilian Kravkov was arrested on a charge of his alleged participation in the "Japanese-SR Terrorist Subversive Espionage Organization". He was executed on 12 October 1937.

- Russian Esperanto writer and translator Nikolai Nekrasov was arrested in 1938, and accused of being "an organizer and leader of a fascist, espionage, terrorist organization of Esperantists". He was executed on 4 October 1938. Another Esperanto writer Vladimir Varankin was executed on 3 October 1938.

- Playwright and avant-garde poet Nikolay Oleynikov was arrested and executed for "subversive writing" on 24 November 1937.

- Yakut writer Platon Oyunsky, seen as one of the founders of modern Yakut literature, died in prison in 1939.

- Russian dramaturge Adrian Piotrovsky, responsible for creating the synopsis for Sergei Prokofiev's ballet Romeo and Juliet, was executed on 21 November 1937.

- Boris Shumyatsky, de facto executive producer for the Soviet film monopoly from 1930 to 1937, was executed as a "traitor" in 1938, following a purge of the Soviet film industry.

- Sinologist Julian Shchutsky was convicted as a "Japanese spy" and executed on 2 February 1938.

- Russian linguist Nikolai Nevsky, an expert on East Asian languages, was arrested by the NKVD on the charge of being a "Japanese spy". On 27 November 1937 he was executed, along with his Japanese wife Isoko Mantani-Nevsky.

- Ukrainian drama writer Mykola Kulish was executed on 3 November 1937. He is considered to be one of the lead figures of Executed Renaissance.

- After sunspot development research was judged un-Marxist, 27 astronomers disappeared between 1936 and 1938. The Meteorological Office was violently purged as early as 1933 for failing to predict weather harmful to the crops.[149]

Western émigré victims

Victims of the terror included American immigrants to the Soviet Union who had emigrated at the height of the Great Depression to find work. At the height of the Terror, American immigrants besieged the US embassy, begging for passports so they could leave the Soviet Union. They were turned away by embassy officials, only to be arrested on the pavement outside by lurking NKVD agents. Many[quantify] were subsequently shot dead at Butovo firing range.[150][better source needed] In addition, 141 American Communists of Finnish origin were executed and buried at Sandarmokh.[151] 127 Finnish Canadians were also shot and buried there.[152]

Executions of Gulag inmates

Political prisoners already serving a sentence in the Gulag camps were also executed in large numbers. NKVD Order no. 00447 also targeted "the most vicious and stubborn anti-Soviet elements in camps", they were all "to be put into the first category"—that is, shot. NKVD Order no. 00447 decreed 10,000 executions for this contingent, but at least three times more were shot in the course of the secret mass operation, the majority in March–April 1938.[66]

Mongolian Great Purge

During the late 1930s, Stalin dispatched NKVD operatives to the Mongolian People's Republic, established a Mongolian version of the NKVD troika, and proceeded to execute tens of thousands of people accused of having ties to "pro-Japanese spy rings".[153] Buddhist lamas made up the majority of victims, with 18,000 being killed in the terror. Other victims were nobility and political and academic figures, along with some ordinary workers and herders.[154] Mass graves containing hundreds of executed Buddhist monks and civilians have been discovered as recently as 2003.[155]

Xinjiang Great Purge

The pro-Soviet leader Sheng Shicai of Xinjiang province in China launched his own purge in 1937 to coincide with Stalin's Great Purge. The Xinjiang War (1937) broke out amid the purge.[156] Sheng received assistance from the NKVD. Sheng and the Soviets alleged a massive Trotskyist conspiracy and a "Fascist Trotskyite plot" to destroy the Soviet Union. The Soviet Consul General Garegin Apresoff, General Ma Hushan, Ma Shaowu, Mahmud Sijan, the official leader of the Xinjiang province Huang Han-chang and Hoja-Niyaz were among the 435 alleged conspirators in the plot. Xinjiang came under virtual Soviet control.[157]

Timeline

The Great Purge of 1936–1938 can be roughly divided into four periods:[158]

- October 1936 – February 1937

- Reforming the security organizations, adopting official plans on purging the elites.

- March – June 1937

- Purging the elites; adopting plans for the mass repressions against the "social base" of the potential aggressors, starting of purging the "elites" from opposition.

- July 1937 – October 1938

- Mass repressions against "kulaks", "dangerous" ethnic minorities, family members of oppositionists, military officers, saboteurs in agriculture and industry.

- November 1938 – 1939

- Stopping of mass operations, abolishing of many organs of extrajudicial executions, repressions against some organizers of mass repressions.

End

In the summer of 1938, Yezhov was relieved from his post as head of the NKVD and was eventually tried and executed. Lavrentiy Beria succeeded him as head. On 17 November 1938, a joint decree of Sovnarkom USSR and Central Committee of VKP(b) (Decree about Arrests, Prosecutor Supervision and Course of Investigation) and the subsequent order of the NKVD undersigned by Beria cancelled most of the NKVD orders of systematic repression and suspended implementation of death sentences. The decree signaled the end of massive Soviet purges.[citation needed]

Michael Parrish argues that while the Great Terror ended in 1938, a lesser terror continued in the 1940s.[159] Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (a Soviet Army officer who became a prisoner for a decade in the Gulag system) presents in The Gulag Archipelago his view of the timeline of all the Leninist and Stalinist purges (1918–1956), in which the 1936–1938 purge may have been simply the one that got the most attention from people in a position to record its magnitude for posterity—the intelligentsia—by directly targeting them, whereas several other waves of the ongoing flow of purges, such as the first five-year plan of 1928–1933's collectivization and dekulakization, were just as huge and just as devoid of justice but were more successfully swallowed into oblivion in the popular memory of the (surviving) Soviet public.[160]

In some cases, high military command arrested under Yezhov were later executed under Beria. Some examples include Marshal of the Soviet Union Alexander Yegorov, arrested in April 1938 and shot (or died from torture) in February 1939 (his wife, G. A. Yegorova, was shot in August 1938); Army Commander Ivan Fedko, arrested July 1938 and shot February 1939; Flagman Konstantin Dushenov, arrested May 1938 and shot February 1940; Komkor G. I. Bondar, arrested August 1938 and shot March 1939. All the aforementioned have been posthumously rehabilitated.[161]

When the relatives of those who had been executed in 1937–1938 inquired about their fate, they were told by NKVD that their arrested relatives had been sentenced to "10 years without the right of correspondence" (десять лет без права переписки). When these ten-year periods elapsed in 1947–1948 but the arrested did not appear, the relatives asked MGB about their fate again and this time were told that the arrested died in imprisonment.[162]

Western reactions

Although the trials of former Soviet leaders were widely publicized, the hundreds of thousands of other arrests and executions were not. These became known in the West only as a few former gulag inmates reached the West with their stories.[163] Not only did foreign correspondents from the West fail to report on the purges, but in many Western nations (especially France), attempts were made to silence or discredit these witnesses;[164] according to Robert Conquest, Jean-Paul Sartre took the position that evidence of the camps should be ignored so the French proletariat would not be discouraged.[164] A series of legal actions ensued at which definitive evidence was presented that established the validity of the former labor camp inmates' testimony.[165]

According to Robert Conquest in his 1968 book The Great Terror: Stalin's Purge of the Thirties, with respect to the trials of former leaders, some Western observers were unintentionally or intentionally ignorant of the fraudulent nature of the charges and evidence, notably Walter Duranty of The New York Times, a Russian speaker; the American Ambassador, Joseph E. Davies, who reported, "proof ... beyond reasonable doubt to justify the verdict of treason";[166] and Beatrice and Sidney Webb, authors of Soviet Communism: A New Civilization.[167] While "Communist Parties everywhere simply transmitted the Soviet line", some of the most critical reporting also came from the left, notably The Manchester Guardian.[168] The American journalist H. R. Knickerbocker also reported on the executions. He called them in 1941 "the great purges", and described how over four years they affected "the top fourth or fifth, to estimate it conservatively, of the Party itself, of the Army, Navy, and Air Force leaders and then of the new Bolshevik intelligentsia, the foremost technicians, managers, supervisors, scientists". Knickerbocker also wrote about dekulakization: "It is a conservative estimate to say that some 5,000,000 [kulaks] ... died at once, or within a few years."[169]

Evidence and the results of research began to appear after Stalin's death. This revealed the full enormity of the Purges. The first of these sources were the revelations of Nikita Khrushchev, which particularly affected the American editors of the Communist Party USA newspaper, the Daily Worker, who, following the lead of The New York Times, published the Secret Speech in full.[170]

Rehabilitation

The Great Purge was denounced by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev following Stalin's death. In his secret speech to the 20th CPSU congress in February 1956 (which was made public a month later), Khrushchev referred to the purges as an "abuse of power" by Stalin which resulted in enormous harm to the country. In the same speech, he recognized that many of the victims were innocent and were convicted on the basis of false confessions extracted by torture. Khrushchev later claimed in his memoirs that he had initiated the process, overcoming objections and protests from the rest of Party leadership, but the transcripts belie this, although they show differences of opinion regarding the contents.[171]

Starting from 1954, some of the convictions were overturned. Mikhail Tukhachevsky and other generals convicted in the Trial of Red Army Generals were declared innocent ("rehabilitated") in 1957. The former Politburo members Yan Rudzutak and Stanislav Kosior and many lower-level victims were also declared innocent in the 1950s. Nikolai Bukharin and others convicted in the Moscow Trials were not rehabilitated until as late as 1988. Leon Trotsky, considered a major player in the Russian Revolution and a major contributor to Marxist theory, was never rehabilitated by the USSR. The book Rehabilitation: The Political Processes of the 1930s–50s (Реабилитация. Политические процессы 30–50-х годов) (1991) contains a large amount of newly presented original archive material: transcripts of interrogations, letters of convicts, and photos. The material demonstrates in detail how numerous show trials were fabricated.[citation needed]

Number of people executed

Official figures put the total number of documentable executions during the years 1937 and 1938 at 681,692,[172][173] in addition to 116,000 deaths in the Gulag,[1] and 2,000 unofficially killed in non-article 58 shootings;[1] whereas the total estimate of deaths brought about by Soviet repression during the Great Purge ranges from 950,000 to 1.2 million, which includes executions, deaths in detention and those who died shortly after being released from the Gulag, as a result of their treatment therein.[1] There were also 16,500 to 50,000 deaths in the deportation of Soviet Koreans which correspond to the purge. According to Robert Conquest, a practice of falsification for lowering the execution numbers was disguising executions with the sentence "10 years without the right of correspondence" which almost always meant execution. All of the bodies identified from the mass graves at Vinnitsa and Kuropaty were of individuals who had received this sentence.[174] Despite this, the lower figure did roughly confirm Conquest's original 1968 estimate of 700,000 "legal" executions and in the preface to the 40th anniversary edition of The Great Terror, Conquest claimed that he had been "correct on the vital matter—the numbers put to death: about one million".[175]

According to J. Arch Getty and Oleg V. Naumov, "popular estimates of executions in the great purges vary from 500,000 to 7 million." However, according to them, "the archival evidence from the secret police rejects the astronomically high estimates often given for the number of terror victims" and "the data available at this point make it clear that the number shot in the two worst purge years [1937–38] was more likely in the hundreds of thousands than in the millions."[176] According to historian Corrina Kuhr, 700,000 people were executed during the Great Purge out of the 2.5 million who were arrested.[2] Professor Nérard François-Xavier estimates the same number of people who were sentenced to death; however, he states that 1.3 million people were arrested.[3]

The Soviets themselves made their own estimates with Vyacheslav Molotov saying "The report written by that commission member…says that 1,370,000 arrests were made in the 1930s. That's too many. I responded that the figures should be thoroughly reviewed".[177]

Stalin's role

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Pre-leadership Leader of the Soviet Union Political ideology Works

Legacy  |

||

Historians with archival access have confirmed that Stalin was intimately involved in the purge. Russian historian Oleg V. Khlevniuk states "theories about the elemental, spontaneous nature of the terror, about a loss of central control over the course of mass repression, and about the role of regional leaders in initiating the terror are simply not supported by the historical record".[178] Besides signing Yezhov's lists, Stalin sometimes gave instructions concerning certain individuals. In one instance, he told Yezhov "Isn't it time to squeeze this gentleman and force him to report on his dirty little business? Where is he: in a prison or a hotel?" In another, while reviewing one of Yezhov's lists, he added to M. I. Baranov's name, "beat, beat!"[179] Stalin also signed 357 lists in 1937 and 1938 authorizing executions of some 40,000 people, and about 90% of these are confirmed to have been shot,[180] this was 7.4% of those executed legally.[181] While reviewing one such list, Stalin reportedly muttered to no one in particular: "Who's going to remember all this riff-raff in ten or twenty years time? No one. Who remembers the names now of the boyars Ivan the Terrible got rid of? No one."[182] Stalin had ordered for 100,000 Buddhist lamas in Mongolia to be liquidated but the political leader Peljidiin Genden resisted the order.[183][184][185]

It is quite possible that Yezhov misled Stalin about the aspects of the purge process.[186] Many people at the time, and also a few subsequent commentators, surmised that the Great Purge wasn't started by Stalin's initiative, so the idea got about that the process was entirely out of control once it had begun.[186] Stalin may have failed to anticipate the catastrophic excesses of the NKVD under Yezhov.[186] Stalin also objected to the large numbers of people that Yezhov was purging. For example, when Yezhov announced that 200,000 party members were expelled, Stalin interrupted him, said that they were "very many" and suggested instead to only expel 30,000 and 600 former Trotskyists and Zinovievists which "would be a bigger victory".[187]

Stephen G. Wheatcroft posits that while the 'purposive deaths' caused by Hitler constitute 'murder', those caused under Stalin fall into the category of 'execution', although in terms of "causing death by criminal neglect and ruthlessness (...) Stalin probably exceeded Hitler".[188] Wheatcroft elaborates:

Stalin undoubtedly caused many innocent people to be executed, but it seems likely that he thought many of them guilty of crimes against the state and felt that the execution of others would act as a deterrent to the guilty. He signed the papers and insisted on documentation. Hitler, by contrast, wanted to be rid of the Jews and communists simply because they were Jews and communists. He was not concerned about making any pretence at legality. He was careful not to sign anything on this matter and was equally insistent on no documentation.[188]

Soviet investigation commissions

At least two Soviet commissions investigated the show-trials after Stalin's death. The first was headed by Molotov and included Voroshilov, Kaganovich, Suslov, Furtseva, Shvernik, Aristov, Pospelov, and Rudenko. They were given the task to investigate the materials concerning Bukharin, Rykov, Zinoviev, Tukhachevsky, and others. The commission worked in 1956–1957. While stating that the accusations against Tukhachevsky et al. should be abandoned, it failed to fully rehabilitate the victims of the three Moscow trials, although the final report does contain an admission that the accusations have not been proven during the trials and "evidence" had been produced by lies, blackmail, and "use of physical influence". Bukharin, Rykov, Zinoviev, and others were still seen as political opponents, and though the charges against them were obviously false, they could not have been rehabilitated because "for many years they headed the anti-Soviet struggle against the building of socialism in USSR".[citation needed]

The second commission largely worked from 1961 to 1963 and was headed by Shvernik ("Shvernik Commission"). It included Shelepin, Serdyuk, Mironov, Rudenko, and Semichastny. The hard work resulted in two massive reports, which detailed the mechanism of falsification of the show-trials against Bukharin, Zinoviev, Tukhachevsky, and many others. The commission based its findings in large part on eyewitness testimonies of former NKVD workers and victims of repressions, and on many documents. The commission recommended rehabilitating every accused with the exceptions of Radek and Yagoda, because Radek's materials required some further checking, and Yagoda was a criminal and one of the falsifiers of the trials (though most of the charges against him had to be dropped too, he was not a "spy", etc.). The commission stated:

Stalin committed a very grave crime against the Communist party, the socialist state, Soviet people and worldwide revolutionary movement...Together with Stalin, the responsibility for the abuse of law, mass unwarranted repressions and death of many thousands of wholly innocent people also lies on Molotov, Kaganovich, Malenkov....

Molotov stated "We would have been complete idiots if we had taken the reports at their face value. We were not idiots." and that "the cases were reviewed and some people were released"[189]

Mass graves and memorials

In the late 1980s, with the formation of the Memorial Society and similar organisations across the Soviet Union at a time of Gorbachev's glasnost ("openness and transparency") it became possible not only to speak about the Great Terror but to begin locating the killing grounds of 1937–1938 and identifying those who lay buried there.

In 1988, for instance, the mass graves at Kurapaty in Belarus were the site of a clash between demonstrators and the police. In 1990, a boulder stone was brought from the former Solovki prison camp in the White Sea, and erected next to KGB headquarters in Moscow as a memorial to all "the victims of political repression" since 1917.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, many more mass graves filled with executed victims of the terror were discovered and turned into memorial sites.[190][191][192][193] Some, such as the Bykivnia killing fields near Kyiv, are said to contain up to 200,000 corpses.[194][195][196][better source needed]

In 2007, one such site, the Butovo firing range near Moscow, was turned into a shrine to the victims of Stalinism. Between August 1937 and October 1938, more than 20,000 people were shot and buried there.[197]

On 30 October 2017, President Vladimir Putin opened the Wall of Sorrow, an official but controversial recognition of the crimes of the Soviet regime.[198]

In August 2021, a mass grave containing between 5,000 and 8,000 skeletons was discovered in Odesa, Ukraine, during exploration works for a planned expansion of Odesa International Airport. The graves are believed to date back to the late 1930s during the purge.[199]

- "Wall of sorrow" at the first exhibition of the victims of Stalinism in Moscow, 19 November 1988

- The Krasny Bor memorial cemetery near Petrozavodsk, Russia

- A monument to victims of political repressions in Rutchenkove settlement, part of Donetsk, Ukraine

- A memorial to victims of Stalinist repression in Tomsk, Russia

- The monumental slab at the entrance to the Sandarmokh burial grounds reads: "People! do not kill one another", Russia

Historical interpretations

The Great Purge has provoked numerous debates about its purpose, scale, and mechanisms. According to one interpretation, Stalin's regime had to maintain its citizens in a state of fear and uncertainty to stay in power (Brzezinski, 1958). Robert Conquest emphasized Stalin's paranoia, focused on the Moscow show trial of "Old Bolsheviks", and analyzed the carefully planned and systematic destruction of the Communist Party. Some others view the Great Purge as a crucial moment, or rather the culmination, of a vast social engineering campaign started at the beginning of the 1930s (Hagenloh, 2000; Shearer, 2003; Werth, 2003).[25] According to an October 1993 study published in The American Historical Review, much of the Great Purge was directed against the widespread banditry and criminal activity which was occurring in the Soviet Union at the time.[200]

Historian Isaac Deutscher regarded the Moscow trials "as the prelude to the destruction of an entire generation of revolutionaries".[201]

Leon Trotsky viewed the excessive violence characteristic of the mass purges as an ideological differentiation between Stalinism and Bolshevism.[202] He summarised his view:

"The present purge draws between Bolshevism and Stalinism not simply a bloody line but a whole river of blood. The annihilation of all the older generation of Bolsheviks, an important part of the middle generation which participated in the civil war, and that part of the youth that took up most seriously the Bolshevik traditions, shows not only a political but a thoroughly physical incompatibility between Bolshevism and Stalinism. How can this not be seen?".[203]

According to Nikita Khrushchev's 1956 speech, "On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences", and to historian Robert Conquest, a great number of accusations, notably those presented at the Moscow show trials, were based on forced confessions, often obtained through torture,[204] and on loose interpretations of Article 58 of the RSFSR Penal Code, which dealt with counter-revolutionary crimes. Due legal process, as defined by Soviet law in force at the time, was often largely replaced with summary proceedings by NKVD troikas.[205]

Valentin Berezhkov, who became Stalin's interpreter in 1941, suggests parallels in his memoir between Hitler's inner party purge and Stalin's mass repressions of Old Bolsheviks, military commanders and intellectuals.[206]

According to historian James Harris, contemporary archival research pokes "rather large holes in the traditional story" weaved by Conquest and others.[207] His findings, while not exonerating Stalin or the Soviet state, dispel the notion that the bloodletting was merely the result of Stalin attempting to establish his own personal dictatorship; evidence suggests he was committed to building the socialist state envisioned by Lenin. The real motivation for the terror, according to Harris, was an exaggerated fear of counterrevolution:[6]

So what was the motivation behind the Terror? The answers required a lot more digging, but it gradually became clearer that the violence of the late 1930s was driven by fear. Most Bolsheviks, Stalin among them, believed that the revolutions of 1789, 1848 and 1871 had failed because their leaders hadn't adequately anticipated the ferocity of the counter-revolutionary reaction from the establishment. They were determined not to make the same mistake.[208]

Two major lines of interpretation have emerged among historians. One argues that the purges reflected Stalin's ambitions, his paranoia, and his inner drive to increase his power and eliminate potential rivals. Revisionist historians explain the purges by theorizing that rival factions exploited Stalin's paranoia and used terror to enhance their own position. Peter Whitewood examines the first purge, directed at the Army, and comes up with a third interpretation that Stalin and other top leaders believing that they were always surrounded by capitalist enemies, always worried about the vulnerability and loyalty of the Red Army.[7] It was not a ploy—Stalin truly believed it. "Stalin attacked the Red Army because he seriously misperceived a serious security threat"; thus "Stalin seems to have genuinely believed that foreign‐backed enemies had infiltrated the ranks and managed to organize a conspiracy at the very heart of the Red Army." The purge hit deeply from June 1937 and November 1938, removing 35,000; many were executed. Experience in carrying out the purge facilitated purging other key elements in the wider Soviet polity.[209][210][211] Historians often cite the disruption as factors in the Red Army's disastrous military performance during the German invasion.[212] Robert W. Thurston reports that the purge was not intended to subdue the Soviet masses, many of whom helped enact the purge, but to deal with opposition to Stalin's rule among the Soviet elites.[213]

See also

- Leningrad affair

- Anti-Rightist Campaign

- Excess mortality in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin

- Index of Soviet Union-related articles

- Timeline of the Great Purge

- History of the Soviet Union (1927–1953)

- Armenian victims of the Great Purge

- Family members of traitors to the Motherland

- Orphans in the Soviet Union#Children of "enemies of the people", 1937–1945

- Mass killings under communist regimes

- Lustration

- Stalinist repressions in Azerbaijan

- Holodomor

Similar events

- Cultural Revolution and the Great Leap Forward (China)

- Hungarian Revolution

- Khmer Rouge genocide (Cambodia)

- 30 September killings (Indonesia)

- Prague Spring (Czechoslovakia)

Similar Polticidal Purges

- Indonesian mass killings of 1965–66 (Indonesia)

- Dirty War (Argentina)

- White Terror (Spain)

- Bodo League massacre (South Korea)

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e Ellman, Michael (2002). "Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 54 (7): 1151–1172. doi:10.1080/0966813022000017177. S2CID 43510161.

The best estimate that can currently be made of the number of repression deaths in 1937–38 is the range 950,000–1.2 million, i.e. about a million. This is the estimate which should be used by historians, teachers and journalists concerned with twentieth century Russian—and world—history

- ^ a b Kuhr, Corinna (1998). "Children of 'Enemies of The People' as Victims of the Great Purges". Cahiers du Monde russe. 39 (1/2): 209–220. doi:10.3406/cmr.1998.2520. ISSN 1252-6576. JSTOR 20171081.

According to latest estimates 2,5 million people were arrested and 700,000 of them shot. These figures are based on reliable archival materials [...]

- ^ a b François-Xavier, Nérard (27 February 2009). "The Levashovo cemetery and the Great Terror in the Leningrad region". Paris Institute of Political Studies.

The Yezhovshchina or Stalin's Great Terror [...] The precise end result of these operations is difficult to establish, but the total of the condemnations is estimated at roughly 1,300,000 of which 700,000 were sentenced to death, most of the others were sentenced to ten years in the camps (document translated in Werth, 2006: 143).

- ^ Conquest 2008, p. 53.

- ^ Brett Homkes (2004). "Certainty, Probability, and Stalin's Great Party Purge". McNair Scholars Journal. 8 (1): 13.

- ^ a b Harris 2017, p. 16.

- ^ a b James Harris, "Encircled by Enemies: Stalin's Perceptions of the Capitalist World, 1918–1941," Journal of Strategic Studies 30#3 [2007]: 513–545.

- ^ "Great Terror: 1937, Stalin & Russia". history.com. 4 October 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ Helen Rappaport (1999). Joseph Stalin: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO. p. 110. ISBN 978-1576070840. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ "Tokaev Comrade X 1956" – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Whitewood, Peter (13 June 2016). "Rethinking Stalin's Purge of the Red Army, 1937–38". University Press of Kansas Blog. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- ^ Uldricks, Teddy J. (1977). "The Impact of the Great Purges on the People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs" (PDF). Slavic Review. 36 (2): 187–204. doi:10.2307/2495035. JSTOR 2495035. S2CID 163664533.

- ^ Conquest 2008, pp. 250, 257–258.

- ^ Goldman, W. (2005). "Stalinist Terror and Democracy: The 1937 Union Campaign". The American Historical Review, 110(5), 1427–1453

- ^ Figes 2007, pp. 227–315.

- ^ Homkes, Brett (2004). "Certainty, Probability, and Stalin's Great Purge". McNair Scholars Journal.

- ^ Ellman, Michael (2002). "Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments". Europe-Asia Studies. 54 (7): 1151–1172. doi:10.1080/0966813022000017177. ISSN 0966-8136. JSTOR 826310.

- ^ Shearer, David R. (2023). Stalin and War, 1918–1953: Patterns of Repression, Mobilization, and External Threat. Taylor & Francis. p. vii. ISBN 978-1-000-95544-6.

- ^ Nelson, Todd H. (2019). Bringing Stalin Back In: Memory Politics and the Creation of a Useable Past in Putin's Russia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-4985-9153-9.

- ^ "Leon Trotsky – Exile and assassination | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Schatman, Max (1938). Behind the Moscow Trials.

- ^ "Joseph Stalin". History.com. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ Hagenloh, Paul. 2000. "Socially Harmful Elements and the Great Terror." pp. 286–307 in Stalinism: New Directions, edited by S. Fitzpatrick. London: Routledge.

- ^ Shearer, David. 2003. "Social Disorder, Mass Repression and the NKVD During the 1930s." pp. 85–117 in Stalin's Terror: High Politics and Mass Repression in the Soviet Union, edited by B. McLaughlin and K. McDermott. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- ^ a b c d e Werth, Nicolas (15 April 2019). "Case Study: The NKVD Mass Secret Operation n° 00447 (August 1937 – November 1938)". Mass Violence and Resistance – Research Network.

- ^ "Great Terror". www.marxists.org.

- ^ a b c d e Broué, Pierre. "The 'Bloc' of the Oppositions against Stalin (January 1980)". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ Kotkin, Stephen, Stalin: Paradoxes of Power 1878–1928

- ^ Andrew & Mitrokhin 2000, pp. 86–87.

- ^ "Trotsky's Struggle against Stalin". The National WWII Museum | New Orleans. 12 September 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ "Who Killed Kirov? 'The Crime of the Century'". www.wilsoncenter.org. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- ^ People's Comissariat of Justice of the U.S.S.R. (1938). Anti-Soviet 'Bloc of Rights and Trotskyites' Heard before the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the U.S.S.R., Verbatim Report. People's Comissariat of Justice of the U.S.S.R. ASIN B0711N78KN.

- ^ Knight, Amy (1999). Who Killed Kirov. Hill & Wang.

- ^ Getty, John Arch; Getty, John Archibald (1987). Origins of the Great Purges: The Soviet Communist Party Reconsidered, 1933–1938. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521335706.