St John the Baptist's Church, Crawley

| St John the Baptist, Crawley | |

|---|---|

The church from the southeast | |

| 51°6′50″N 0°11′19″W / 51.11389°N 0.18861°W | |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Churchmanship | Modern Catholic, Informal Charismatic |

| History | |

| Dedication | John the Baptist |

| Administration | |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Diocese | Chichester |

| Archdeaconry | Horsham |

| Deanery | East Grinstead |

| Parish | Crawley, St John the Baptist |

| Clergy | |

| Priest(s) | Rev. Steve Burston |

St John the Baptist's Church is an Anglican church in Crawley, West Sussex, England. It is the parish church of Crawley, and is the oldest building in the town centre, dating from the 1250[1][2]—although many alterations have been made since, and only one wall remains of the ancient building.[2] In September 2017, a team from St Peter's Brighton began a new phase in the life of St John's Crawley. St John's offer a variety of services, traditional and informal, and contemporary services.

St John's is a Holy Trinity Brompton (HTB) network church.

History

In the Norman era, Slaugham and Cuckfield were the most important places in the north of the county of Sussex.[2] When Crawley first started to develop as a village in the 13th century, it was in the parish of Slaugham[1] in the Hundred of Buttinghill (hundreds were ancient divisions of land covering several parishes).[3] As the new village was distant from the parish church at Slaugham (St Mary's), several miles south, a stone church was built as a chapel of ease.[2] It is known to have existed before 1267, when it was passed on in a will,[4] and it was still the daughter church of Slaugham in 1291; but by the early 15th century it was referred to as a "free" church and a "permanent chantry".[2] The parish of Crawley was therefore established separate from Slaugham at some point, probably by the end of the 14th century,[5] and St John the Baptist's was regarded as its parish church by the time chantries were abolished in the 1540s.[6] Crawley was a small, very narrow, split parish, and did not cover the whole of the village of Crawley: the boundary between it and the parish of Ifield—and between the Hundred of Buttinghill and the Hundred of Burbeach, in which Ifield lay—ran up the middle of the High Street.[7][8] The detached part of Crawley parish consisted of heavily forested land and one farm near Pease Pottage.[8] The total area of the parish was less than 800 acres (300 ha); Ifield parish was six times larger, in contrast.[7]

The first additions to the structure came in the 15th century, when a tall tower was added at the western end, the windows in the nave were enlarged and a rood screen was installed between the chancel and the nave.[9] The nave roof was also rebuilt at this time, and the earliest surviving memorial carvings and stones in the church are also 15th-century.[5][10]

By the 16th century, Crawley's development into a thriving market village meant that its parish was much more important than that of Slaugham, and the connection between their two churches was legally severed.[11] At least 150 people regularly attended the church,[12] but its income was modest and priests frequently moved on to richer parishes.[13] The building fell into disrepair in the 17th and 18th centuries. In the Chichester Diocesan Survey of 1724, it gives:

"4 bells, but onely one in order, 3 being crackt". These bells were melted down, and Thomas Lester of Whitechapel cast 2 bells out of them in 1742. The treble and tenor weighed 3-3-15cwt and 6-0-11cwt respectively. They were inscribed:

1 (Treble): THOMAS LESTER OF LONDON MADE ME 1742 / FRANCIS SMITH CH WARDEN

2 (Tenor) : FRANCIS SMITH CH WARDEN 1742 T.L. FECIT

Lester (master of the Whitechapel foundry between 1738 - 1769) gave Sussex many bells, our closest surviving examples are at Horsham, St Mary the Virgin. [14][15]

Major changes took place in the 19th century. The tower partially rebuilt and heightened by 1814, although the original stone was reused.[6][10][16] Some more work took place in 1845,[6] but the greatest changes happened in 1879 and 1880. A new north aisle was added, a porch was built on the north side, the chancel was completely rebuilt and reordered, and an organ chamber was built.[6][10][16][17] Nikolaus Pevsner has criticised the resulting appearance of the church, calling it "dully Victorian" and noting that its best feature is the unrestored 15th-century nave roof.[16]

At the same time, the church decided to restore their church bells. The two bells by Lester became cracked, and their frame had rotted away. It was decided to install a new peal of 8 bells in the tower by the late Croydon firm Gillett, Bland & Company. The bells are inscribed as follows (A / denotes the end of line):

1 (Treble): CAST BY GILLETT, BLAND & Co, CROYDON, 1880. / GLORY

2: CAST BY GILLETT, BLAND & Co, CROYDON, 1880. / SIR . W . W . BURRELL / HONOUR

3: CAST BY GILLETT, BLAND & Co, CROYDON, 1880. / PRAISE

4: CAST BY GILLETT, BLAND & CO, CROYDON, 1880. / THANKSGIVING

5: CAST BY GILLETT, bLAND & CO, CROYDON, 1880. / JOY

6: CAST BY GILLETT, BLAND & CO, CROYDON, 1880. / SIR . R . B . LENNARD / BROTHERLY LOVE

7: CAST BY GILLETT, BLAND & CO, CROYDON, 1880. / J . B . LENNARD RECTOR / WORSHIP

8 (Tenor): CAST BY GILLETT, BLAND & CO, BELL FOUNDERS & CLOCK MAKERS CROYDON 1880 / R LODER / PRAYER

Bell 8 also has a few floral ornaments inscribed. The bells are hung in an oak bell frame arranged in what's known as an 8.3 layout.

In 1931, bell 3 was recast by Mears & Stainbank after it cracked. At the same time, the tenor was rehung on plain bearings. The rest of the bells were rehung on ball bearings 4 years later by John Taylor & Co. Some of the wheels were replaced in 1985, and the 5th was rehung on a new headstock by Whitechapel in 1999. When the bells were restored in 1880, an Ellacombe and Seage's apparatus were installed so that the bells could be controlled by 1 person, and that they could be rung in silence.[18]

The church's location just east of the High Street[16] meant that it was very close to the boundary of Ifield parish. People who lived on or around the west side of the High Street would often attend St John the Baptist's although their parish church was St Margaret's. One such worshipper was Mark Lemon, founding editor of the satirical magazine Punch. Having adopted Crawley as his home town, he lived at Vine Cottage on the west side of the High Street, and regularly attended St John the Baptist's instead of St Margaret's.[19] However, his substantial girth caused him problems: he had to sit in the gallery because there were no pews large enough to accommodate him in the nave.[20]

The church, graveyard and church walk are reportedly haunted a number of paranormal sightings have happened over the years. The churchyard contains the war graves of two soldiers of World War I and an airman of World War II.[21]

Architecture

The church is built of Sussex limestone. The chancel roof is tiled, but the rest of the church is roofed with slabs of local stone.[10] The south wall of the nave is original,[16] although it has some 15th-century alterations; the nave ceiling is also from this era, and features wind bracing and tie beams. The tower, rebuilt in the 19th century, is in three stages and features mediaeval carvings.[10][16] The pulpit is 17th-century;[16] the altar rails are from that century or early in the 18th.[10][16] There is some stained glass in the 19th-century north aisle and the east end of the chancel.[16] The oldest internal fixture is the marble font, which is 13th-century.[10]

The parish

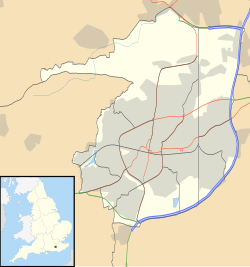

In October 2017, the parish size was reduced to include Crawley town centre, its northernmost point being where Kilnmead road meets the London road, and southernmost where Goffs Park road meets the Brighton Road.

The previous parish covered by the church was much larger than the ancient parish of Crawley. It covered most of the town west and north of the railway line between Gatwick Airport and Crawley railway stations, and up to the boundary of the airport. The boundary was defined by the A23 London Road from its junction with the Horsham Road in Southgate to the edge of the Manor Royal industrial estate at County Oak; the southern perimeter road of Gatwick Airport—incorporating all the land and buildings in the former village of Lowfield Heath; some farmland and residential development east of the railway line at Tinsley Green; the railway line from Tinsley Green to Southgate Avenue, near Crawley railway station; and the northern part of the Southgate neighbourhood.[22]

There are five extant churches in the parish.[22] St Peter's in West Green predates the New Town, having been built between 1892 and 1893 to a design by architect W. Hilton Nash.[23] Richard Cook, owner of one of Crawley's main building firms, constructed it.[20] It replaced a chapel of ease to St Margaret's Church, Ifield: although West Green was in the parish of Ifield at the time, it was remote from the parish church. Although the Diocese of Chichester would not pay for a separate church, it accepted St Peter's, which was built with private money, when it was offered.[24] The church later gained its own parish, which was then absorbed by the parish of St John the Baptist. St Elizabeth's in the centre of the Northgate neighbourhood was built in 1965, and like St John the Baptist's follows a "Modern Catholic" style of worship.[25] St Richard's is another modern church serving the Three Bridges neighbourhood. A fifth church, St Michael and All Angels, is notionally within the parish but is no longer used for Anglican worship. William Burges designed and built this yellow sandstone 13th century-style French Gothic[26] church in 1867[27] to serve the village of Lowfield Heath, which was then in the parish of Charlwood in Surrey.[28] The establishment and rapid development of Gatwick Airport next to Lowfield Heath swamped the small village, eventually destroying it: all buildings except the church, which was listed at Grade II* in 1948,[26] were demolished to make way for warehouses and extensions to the airport boundary.[29] (The church is approximately 500 feet (150 m) from the runway.) The Diocese of Chichester stopped using the church for services in 2004; in March 2008 it allowed a Seventh-day Adventist congregation to use the building as its place of worship.[28] Horley Seventh-Day Adventist Church was formed as a church plant in May 2005 and was formally established in January 2008.[30]

The Church Today

In September 2017 a team led by Steve and Liz Burston from St Peter's Brighton began a new phase in the life of St John's. There are a variety of services, traditional and informal, contemporary services in order to seek to honour the past, navigate the present and build for the future.

St John's Crawley run an Alpha course every term, providing an opportunity to freely discuss some of the bigger questions of life, faith and purpose within a Christian context. They also run social outreach programmes, such as The Bridge Café and Turning Point. As well as Sunday services, there are groups that meet throughout the week, seeking to deepen faith and grow in community. As a church St John's firmly believe in the Christian witness of churches working together across Crawley, both in social mission and prayer. As a result, prayer and church unity are at the heart of their values.

See also

References

- ^ a b "St John's Church". Crawley Borough Council website. Crawley Borough Council. 2008. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Gwynne, Peter (1990). "4 – The Normans". A History of Crawley (1st ed.). Chichester: Phillimore & Co. p. 38. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ Gwynne, Peter (1990). "3 – The Saxon Settlers". A History of Crawley (1st ed.). Chichester: Phillimore & Co. p. 23. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ Gwynne, Peter (1990). "4 – The Normans". A History of Crawley (1st ed.). Chichester: Phillimore & Co. p. 40. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ a b Gwynne, Peter (1990). "3 – The Saxon Settlers". A History of Crawley (1st ed.). Chichester: Phillimore & Co. p. 57. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ a b c d Salzman, L. F., ed. (1940). "A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 7 – The Rape of Lewes". Victoria County History of Sussex. British History Online. pp. 144–147. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ^ a b Gwynne, Peter (1990). "3 – The Saxon Settlers". A History of Crawley (1st ed.). Chichester: Phillimore & Co. p. 22. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ a b Gwynne, Peter (1990). "4 – The Normans". A History of Crawley (1st ed.). Chichester: Phillimore & Co. p. 42. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ Gwynne, Peter (1990). "3 – The Saxon Settlers". A History of Crawley (1st ed.). Chichester: Phillimore & Co. p. 56. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Historic England (2007). "Parish Church of St John the Baptist, High Street (east side) (1298875)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- ^ Gwynne, Peter (1990). "7 – The Sixteenth Century: The First Building Boom". A History of Crawley (1st ed.). Chichester: Phillimore & Co. p. 74. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ Gwynne, Peter (1990). "7 – The Sixteenth Century: The First Building Boom". A History of Crawley (1st ed.). Chichester: Phillimore & Co. p. 75. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ Gwynne, Peter (1990). "7 – The Sixteenth Century: The First Building Boom". A History of Crawley (1st ed.). Chichester: Phillimore & Co. p. 76. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ https://thebellsofsussex.weebly.com/crawley-st-john-the-baptist.html [bare URL]

- ^ Gwynne, Peter (1990). "9 – Georgian England: the Peaceful Years at Home". A History of Crawley (1st ed.). Chichester: Phillimore & Co. pp. 94–96. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Nairn, Ian; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1965). The Buildings of England: Sussex. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 202. ISBN 0-14-071028-0.

- ^ "Dove Details". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers website. Sid Baldwin, Ron Johnston and Tim Jackson on behalf of the Central Council of Church Bell Ringers. 24 February 2008. Retrieved 12 March 2008.

- ^ https://thebellsofsussex.weebly.com/crawley-st-john-the-baptist.html [bare URL]

- ^ Gwynne, Peter (1990). "9 – Georgian England: the Peaceful Years at Home". A History of Crawley (1st ed.). Chichester: Phillimore & Co. p. 95. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ a b Gwynne, Peter (1990). "10 – Victorian Prosperity". A History of Crawley (1st ed.). Chichester: Phillimore & Co. p. 119. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ [1] CWGC Cemetery report, details obtained from casualty record.

- ^ a b "Crawley: St John the Baptist – About our Parish". A Church Near You website. Oxford Diocesan Publications Ltd. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- ^ Nairn, Ian; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1965). The Buildings of England: Sussex. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 205. ISBN 0-14-071028-0.

- ^ Gwynne, Peter (1990). "10 – Victorian Prosperity". A History of Crawley (1st ed.). Chichester: Phillimore & Co. pp. 121–123. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ "Crawley: St Elizabeth, Crawley". A Church Near You website. Oxford Diocesan Publications Ltd. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- ^ a b Historic England (2007). "Church of St Michael and All Angels, Church Road (1187081)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- ^ Nairn, Ian; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1965). The Buildings of England: Sussex. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 204. ISBN 0-14-071028-0.

- ^ a b "The History and Background of St Michael & All Angels, Lowfield Heath". Horley Seventh-Day Adventist Church website. Horley Seventh-Day Adventist Church. 2007. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- ^ Gwynne, Peter (1990). "12 – The New Town: Maturity". A History of Crawley (1st ed.). Chichester: Phillimore & Co. p. 170. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ "Horley Seventh-Day Adventist Church: About Us". Horley Seventh-Day Adventist Church website. Horley Seventh-Day Adventist Church. 2007. Retrieved 22 November 2008.