Shropshire Union Railways and Canal Company

| Shropshire Union Railways and Canal Co | |

|---|---|

The Shropshire Union Canal near Norbury Junction | |

| Specifications | |

| Maximum boat length | 70 ft 0 in (21.34 m) |

| Maximum boat beam | 7 ft 0 in (2.13 m) |

| Status | Most open |

| Navigation authority | Canal and River Trust |

| History | |

| Original owner | Ellesmere and Chester Canal Co |

| Date of act | 1846 |

| Date of first use | 1846 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Ellesmere Port |

| End point | Autherley Junction |

| Branch(es) | Middlewich Branch; Llangollen Branch; Montgomery Canal; Shrewsbury Canal; Shropshire Canal; Stafford to Shrewsbury Railway |

The Shropshire Union Railways and Canal Company was a Company in England, formed in 1846, which managed several canals and railways. It intended to convert a number of canals to railways, but was leased by the London and North Western Railway (LNWR) from 1847, and although they built one railway in their own right, the LNWR were keen that they did not build any more. They continued to act as a semi-autonomous body, managing the canals under their control, and were critical of the LNWR for not using the powers which the Shropshire Union Company had obtained to achieve domination of the markets in Shropshire and Cheshire by building more railways.

The company grew out of the amalgamation of the Chester Canal with its branch to Middlewich and the Birmingham and Liverpool Junction Canal, which ran from Nantwich to Autherley. They took over the Eastern and Western branches of the Montgomery Canal, the Shrewsbury Canal and leased the Shropshire Canal. Although plans to convert them to railways had been dropped by 1849, the LNWR bought the Shropshire Canal outright in 1857, following severe subsidence, and used it as the route for a railway to Coalport, opened in 1861.

Most of the profits came as a result of the company acting as a carrier, rather than from tolls. In addition to running narrow boats on the canals, they had a thriving business carrying goods across the River Mersey, between Liverpool, Ellesmere Port, and Birkenhead. They made a healthy operating profit until the 1870s, but this then diminished during the next 30 years. They looked at upgrading the canal to take larger vessels in the 1890s, prompted by the opening of the Manchester Ship Canal, but this did not occur. They saw a brief improvement in their financial position in the early 20th century, but this collapsed with the onset of the First World War. Government subsidies sustained them until 1920, but rising wage costs and the 8-hour day resulted in them ceasing to act as a carrier, and the LNWR bought the company in late 1922. On 1 January 1923, the LNWR became part of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS), with the passing of the Railways Act 1921 (Grouping Act). The Montgomery Canal closed in 1936 after a major breach, and most of the canals were closed under the provisions of an abandonment order obtained in 1944.

The Ellesmere Port to Autherley section and the branch to Middlewich remained open, and have since been named the Shropshire Union Canal. The branch to Llangollen, which was retained as a water feeder, has been reopened in the leisure age as the Llangollen Canal, and parts of the Montgomery Canal have been restored, with ongoing plans for a full restoration. A fledgling scheme to conserve and reopen the Shrewsbury Canal is having some success, and a small part of the Shropshire Canal is now part of the Ironbridge Gorge Museums. Part of the Stafford to Shrewsbury Line, the only railway built by a canal company, remains open from Shrewsbury to Wellington, and is served by Transport for Wales.

History

In 1844, the Ellesmere and Chester Canal Company, which owned the broad canals from Ellesmere Port to Chester and from Chester to Nantwich, with a branch to Middlewich, began discussions with the narrow Birmingham and Liverpool Junction Canal, which ran from Nantwich to Autherley, where it joined the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal. The two companies had always worked together, in a bid to maintain their profits against competition from the railways, and amalgamation seemed to be a logical step. An agreement was worked out by August, and the two companies then sought an act of Parliament to authorise the takeover. This was granted as the Ellesmere and Chester Canal Company Act 1845 (8 & 9 Vict. c. ii) on 8 May 1845, when the larger Ellesmere and Chester Canal Company was formed.[1]

Reformation as a joint canal–railway company

Shropshire Union Canals | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Almost immediately, a committee was set up to look at options for converting all or part of the canals into railways, and extending the network. Although they had already tried using a steam tug to haul a train of boats, they realised that not all of their canals were suitable for such use, and that a locomotive on a railway with good gradients offered a better solution. The Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal were alarmed by the announcement that many of the canals might close, on the basis that removal of one would have a serious effect on another, and sought to oppose the action.[2]

The committee met with the railway engineer Robert Stephenson on 24 July 1845, who suggested that various schemes should be joined together to avoid competition in Parliament. George Loch, who was on the board of the Ellesmere and Chester Canal, worked on the details for what would become the Shropshire Union, which involved amalgamation of several railway and canal companies. Among the canals to be included in the larger scheme were the Eastern and Western branches of the Montgomery Canal, the Shrewsbury Canal and the Shropshire Canal. While much of the canal network would be converted to railways, some 80 to 90 miles (130 to 140 km) would be retained in water, including the Shrewsbury Canal, the Shropshire Canal, and the line from Ellesmere Port via Barbridge to Middlewich, which served the trade in salt.[3]

Four new railways were proposed. The first would run from Crewe to Newtown, via Nantwich, Whitchurch, Ellesmere, Oswestry and Welshpool, with a branch from Whitchurch to Wem. At Newtown, it would meet with a projected railway to Aberystwyth. The second would run from the North Staffordshire Railway at Stone or Norton Bridge to Stafford, continuing through Newport, Donnington and Wellington to Shrewsbury. A third would follow the course of the River Severn from Shrewsbury to Worcester, with a branch from Ironbridge to Donnington and Wellington. The final one would connect Wolverhampton to the Chester and Crewe Railway, passing through Market Drayton and Nantwich. The proposed capital for the venture was £1.4 million, and the engineers were listed as William Cubitt, Robert Stephenson and W. A. Provis, the resident engineer for the Ellesmere and Chester Canal.[3]

| Shropshire Union Railways and Canal (Chester and Wolverhampton Line) Act 1846 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for making a Railway from the Chester and Crewe Branch of the Grand Junction Railway at Calveley to Wolverhampton; and for other Purposes connected therewith. |

| Citation | 9 & 10 Vict. c. cccxxii |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 3 August 1846 |

| Shropshire Union Railways and Canal (Shrewsbury and Stafford Railway) Act 1846 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for making a Railway from Shrewsbury to Stafford, with a Branch to Stone; and for other Purposes. |

| Citation | 9 & 10 Vict. c. cccxxiii |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 3 August 1846 |

| Shropshire Union Railways and Canal (Newton to Crewe with Branches) Act 1846 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for making a Railway from Newtown in the County of Montgomery to Crewe in the County of Chester, with Branches; and for other Purposes connected therewith. |

| Citation | 9 & 10 Vict. c. cccxxiv |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 3 August 1846 |

The joint company obtained acts of Parliament in 1846, the Shropshire Union Railways and Canal (Newton to Crewe with Branches) Act 1846 (9 & 10 Vict. c. cccxxiv), Shropshire Union Railways and Canal (Shrewsbury and Stafford Railway) Act 1846 (9 & 10 Vict. c. cccxxiii), and the Shropshire Union Railways and Canal (Chester and Wolverhampton Line) Act 1846 (9 & 10 Vict. c. cccxxii), to cover the first three of the four railways, and to reform itself as the Shropshire Union Railways and Canal Company (SUR&CC). The new company was authorised to take over the Shrewsbury Canal and to buy the Montgomery Canal and the Shropshire Canal.[4] The intent behind the acts was to build railways at a reduced cost, by using the existing routes of the canals the company owned.[5] New share capital of £3.3 million could be raised, with an additional £1.1 million if required. Holders of shares in the existing canal companies exchanged them for new shares. The Ellesmere and Chester was valued at £250,004, the Birmingham and Liverpool Junction at £150,000, and the Shrewsbury at £75,000. The company carried forward debts and liabilities of £800,207.[6]

Takeovers

Stafford– Shrewsbury line |

|---|

The Shropshire Union Company bought the eastern branch of the Montgomery Canal in February 1847, for £78,210. Three years later, on 5 February 1850, they paid £42,000 for the western branch. The Shropshire Canal had been valued at £72,500, but rather than buy it, the company decided to lease it from 1 November 1849, paying £3,125 per year. They also started work on the Shrewsbury and Stafford Railway, confident that it would not result in the canals losing revenue.[6]

However, dealing with ever-expanding railway companies proved difficult. They had originally formed a contract with the Shrewsbury, Wolverhampton, Dudley and Birmingham project, which was subsequently leased to the London and Birmingham Railway. The London and Birmingham saw the Shropshire Union's fourth railway proposal, from Wolverhampton to Crewe, as an important part of their main line to Holyhead, and formed an alliance with the Crewe and Holyhead Railway and the Manchester and Birmingham Railway. The three companies would support the Shropshire Union, against the Grand Junction Railway, who were proposing an alternative route between Wolverhampton and Crewe. The support was short-lived, as the London and Birmingham Railway, the Manchester and Birmingham Railway, and the Grand Junction Railway amalgamated on 1 January 1846, to become the London and North Western Railway (LNWR), and suddenly the Shropshire Union route was a threat.[7]

By the autumn of 1846, the LNWR had offered to lease the Shropshire Union, and the directors felt that a guaranteed income from a powerful company was probably better than most other options. They agreed to the terms in December, and the LNWR obtained an act of Parliament[which?] in June 1847 to authorise the arrangement. The Shrewsbury and Stafford Railway was opened on 1 June 1849, and lease payments began a month later on 1 July. The arrangement of the lease was not fully completed until 25 March 1857, but the LNWR, struggling with their own success, persuaded the Shropshire Union not to build any more railways, in exchange for a commitment to servicing the canal debts. The Shropshire Union thus lost its independence after a very short period, but continued to manage the canals under its control, and in this they had a remarkably free hand.[8]

By 1849, the plan to turn the canals into railways had been dropped,[5] and the company were leasing the Shropshire Canal, which ran from Wrockwardine Wood where there was a junction with the Trench branch of the Shrewsbury Canal, to Coalport, on the River Severn.[9] Following the Great Western Railway's take-over of the Shrewsbury and Birmingham's railway line through Oakengates and its branch from Madeley Wood to Lightmoor on 1 September 1854, the Shropshire Union manager, Robert Skey, recommended to the LNWR that the Shropshire Canal should be converted to a railway in January 1855, but no action was taken. However, after a series of breaches later that year and in 1856, the LNER were faced with spending £30,000 on repairing the canal. Instead, they obtained an Act of Parliament in 1857, which allowed them to buy the canal for £62,500, close the northern section from Wrockwardine Wood to the Windmill inclined plane, and build a railway line along its course. The closure was delayed until 1 June 1858, and the railway branch to Coalport opened in mid-1861.[10]

Competition

The LNWR had sought to build a railway connecting Shrewsbury, Welshpool, Oswestry and Newtown in 1853, but had withdrawn the bill from Parliament after discussions with the Great Western Railway. The Oswestry and Newtown Railway was subsequently built by the Great Western, with support from former shareholders of the Montgomery Canal, who had hoped that selling the canal to the Shropshire Union would result in it being converted to a railway. It was completed in June 1861, and ran parallel to the Montgomery Canal. Another line opened in 1864, the Oswestry, Ellesmer and Whitchurch Railway, which was part of the Cambrian Railway. The Shorpshire Union negotiated with both companies on rates, and managed to keep the canal rates slightly lower than those on the railways.[11]

At their annual meeting in September 1861, Robert Skey stated that the canals brought some £60,000 in trade to the LNWR each year. However, the relationship with the LNWR was not always smooth, who were castigated at the 1862 meeting for failing to use powers which the Shropshire Union already had, to gain control of Shropshire and Montgomeryshire through the construction of new railways.[12] At that time, the Shropshire Union were busy converting and extending a tramway which ran from Pontcysyllte to Afon-eitha to allow locomotives to run on it. The work was finished in 1867, and ran for a time with a borrowed locomotive, until they bought their own from Crewe works in 1870. To save money on the maintenance of Trench Inclined Plane on the Shrewsbury Canal, the company leased Lubstree Wharf on the Humber Arm of the Newport Branch from 1870, and built a railway to Lilleshall Works, which provided most of the traffic on the Shrewsbury Canal.[13]

By 1869, the Shropshire Union had a thriving business carrying goods from a base at Chester Basin, Liverpool, across the River Mersey to Ellesmere Port and Birkenhead. The LNWR was also involved in cross-river trade, using private carriers, and this was transferred to the Shropshire Union in 1870, after they had suggested it. The company bought out the lighterage business of William Oulton in 1870, moved their base from Chester Basin to Manchester Basin, and bought the Mersey Carrying Co in 1883. Under the terms of the lease with the LNWR, the company was limited in the types of goods they could carry, and although they made a healthy operating profit until the late 1860s, this did not cover the interest on debts or dividends. Between 1850 and 1870, receipts had risen from £104,638 to £145,976, but costs had risen much faster, and the average surplus had fallen from £45,885 to £11,717. Most of the income was generated by their carrying business, rather than by tolls for use of the canal network.[14]

Haulage of their boats by horses had been contracted out to Bishtons until the mid-1860s, when the company took that function back, so that they could use steam haulage if that proved desirable, but in practice the only route where steam tugs were used was on the Ellesmere Port to Chester section. Horses were still thought to be cheaper, and remained in use until the carrying business ceased.[15] In order to fulfill the carrying business, they owned 213 narrowboats in 1870, rising to 395 in 1889 and 450 in 1902.[5] In 1888 they experimented with locomotive haulage, running on 18 in (457 mm) gauge tracks, at Worleston on the Middlewich Branch. Their engineer, G R Jebb, wrote a report on the experiment, but no further action was taken.[16]

The next development was at Ellesmere Port, where the Manchester Ship Canal cut off the Port from the River Mersey. From 16 July 1891, all traffic from the port had to pass along the canal, and entered the river through Eastham Lock. Access to the river had previously been by a tidal basin, but this was fitted with double gates where it connected to the ship canal. The Shropshire Union spent £37,850 constructing a new quay next to the gates, 1,800 feet (550 m) long, and suitable for ships up to 4,000 tons. While the ship canal was under construction, the Shropshire Union investigated the cost of upgrading their line from Ellesmere Port to Autherley to take larger barges. Jebb estimated that it would cost around £13,500 per mile (£8,400 per km), so the total cost would have been £891,475. In the autumn of 1890, they were discussing plans for a large canal from the Mersey to Birmingham via the Potteries with the North Staffordshire Railway. Neither scheme came to fruition, but the Shropshire Union spent large amounts of money on building better wharves and warehouses at many of the Pottery towns.[17]

Decline

For the final 30 years of the 19th century, the Shropshire Union network had made a small operating surplus, although it did not cover dividends or interest in its debts.[18] The situation improved during the early years of the 20th century, but collapsed again at the start of the First World War. Government subsidies propped up the operation when hostilities ceased, but wages had increased significantly, the eight-hour day had been extended to boatmen and rivermen, and raw materials were more expensive. When subsidies were withdrawn from 14 August 1920, the operation was no longer viable. Boating families who lived on 202 boats were told that all carrying would cease, although the waterways would stay open, in the hope that private boats might use them. The Ellesmere Port facilities were leased to the Manchester Ship Canal, for a period of 50 years, while the Great Western Railway took over those at Liverpool.[19]

In late 1922, the LNWR bought out the company, under the provisions of the L&NWR (SUR&CC) Preliminary Absorption Scheme, by exchanging all remaining Shropshire Union stock for LNWR stock. A few days afterwards, at the start of 1923, the LNWR was absorbed into the London Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) as part of the Grouping, under which most of the railways of Britain were formed into four groups.[20]

A period of steady decline set in, with reduced maintenance making it more difficult for boats to operate. The Weston Branch of the Montgomery Canal had closed in 1917, following a breach near Hordley,[21] and most of the main line was closed in February 1936 when a breach occurred just to the north of the aqueduct over the River Perry, about a mile (1.6 km) from Frankton Junction.[22]

Finally, the London Midland and Scottish Railway obtained an act of Parliament, the London Midland and Scottish Railway (Canals) Act 1944 (8 & 9 Geo. 6. c. ii) allowing abandonment in 1944, which resulted in the closure of 175 miles (280 km) of canals under their control. For the Shropshire Union system, this included the Montgomery Canal, the Shrewsbury Canal, and the remaining short section of the Shropshire Canal,[21] leaving only the main line from Ellesmere to Autherley, and the branch to Middlewich. The branch to Llangollen was also retained, but only as a feeder to supply water to the canal. The other main sources of water were the Belvide Reservoir, near the A5 road at Brewood, and the outflow from the Barnhurst Sewage Treatment Works at Autherley Junction.[5]

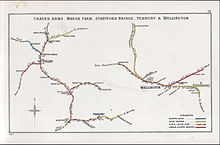

Shropshire Union railways

The Shropshire Union Company constructed and ran one of the few railways in England which were built by a canal company. The railway was the Stafford to Shrewsbury Line, via Newport and Wellington. The Shropshire Union Company were solely responsible for the section from Stafford to Wellington, but the building and operation of the 10.5-mile (17 km) long section between Shrewsbury and Wellington was shared with the Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway.[23][24]

After the LNWR take over of the Shropshire Union network, the Shrewsbury and Wellington Railway was operated as a Joint railway by the Great Western Railway and the LNWR.[24] The Stafford to Shrewsbury Railway opened on 1 June 1849 and was 29.25 miles (47 km) in length.[25] The London and North Western Railway leased the line from July 1847, before it was complete.

Shropshire Union railways today

The Shrewsbury and Wellington section is still in use today by West Midlands Trains and Transport for Wales.

Passenger services on the Stafford to Wellington section ended on 7 September 1964. Goods services ceased between Stafford and Newport on 1 August 1966 and this branch from Wellington was cut back to Donnington on 22 November 1969.

In June 2009, the Association of Train Operating Companies, in its Connecting Communities: Expanding Access to the Rail Network report, which proposed a £500m scheme to open 33 stations on 14 lines closed in the Beeching Axe, including seven new parkway stations, identified the line from Stafford to Wellington as a potential link that could feasibly be re-opened.[26][27]

The canals today

As of 2017, the main line from Ellesmere Port to Autherley and the branch to Middlewich are still open; they are known as the Shropshire Union Canal. The branch from Hurleston Junction to Llangollen has been reopened for navigation, having been promoted as suitable for pleasure boating from the mid-1950s, and has been re-branded as the Llangollen Canal.[5]

The Montgomery Canal has been partially re-opened. The first section restored was at Welshpool, when the line of the canal was threatened by a bypass, and this isolated section was reopened in 1969.[28] The section southwards from Frankton Junction has been restored and opened progressively since 1987,[29] with additions in 1995,[30] 1996,[31] 2003, 2007 and the stretch from Redwith Bridge to Pryce's Bridge in July 2014. In 2023 an extension to Crickheath Wharf was opened allowing boats to navigate from Gronwen ,the previous limit of navigation. Also in 2023, work began on rebuilding Schoolhouse Bridge which had been filled-in in the 1960's and is the last obstruction of the channel in Shropshire. There are ongoing efforts to complete the restoration of most of the remaining un-navigable sections.[32] The Welsh Government have announced the spending of Levelling Up Fund money on removing two dropped bridges west of Llanymynech and other works.

A Trust has been set up to conserve the remains of the Shrewsbury Canal, with a view to reopening it in the longer term.[33] A feasibility study and a detailed engineering report were commissioned and completed in 2004, and concluded that there were no major engineering obstacles to a full reopening.[34][35]

A short section of the Shropshire Canal including the Hay Inclined Plane has been incorporated into the Ironbridge Gorge Museums. The canal contains water near the derelict Madeley Wood Brick and Tile Works, and the section at the bottom of the inclined plane at Coalport is also in water.[36] The inclined plane was partially restored in the 1970s, and further restoration took place in the 1990s.[37]

References

- ^ Hadfield 1985, pp. 188–189

- ^ Hadfield 1985, pp. 231–232.

- ^ a b Hadfield 1985, p. 232.

- ^ "Shropshire Routes to Roots: 8. The Shropshire Union". Shropshire County Council. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Nicholson 2006, p. 81.

- ^ a b Hadfield 1985, p. 233.

- ^ Hadfield 1985, pp. 233–234.

- ^ Hadfield 1985, pp. 234–235.

- ^ "Shropshire Routes to Roots: 9. From canal to railway". Shropshire County Council. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ Hadfield 1985, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Hadfield 1985, p. 238.

- ^ Hadfield 1985, pp. 238–239.

- ^ Hadfield 1985, p. 239.

- ^ Hadfield 1985, p. 240.

- ^ Hadfield 1985, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Hadfield 1985, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Hadfield 1985, p. 245.

- ^ Hadfield 1985, pp. 247–248.

- ^ Hadfield 1985, pp. 248–249.

- ^ Hadfield 1985, pp. 249–250.

- ^ a b Hadfield 1985, p. 250.

- ^ Nicholson 2006, p. 66.

- ^ "The Shrewsbury & Birmingham Railway". Wolverhampton University. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ a b Casserley 1968.

- ^ Awdry 1990, pp. 42, 102–103.

- ^ "Connecting Communities – Expanding Access to the Rail Network" (PDF). London: Association of Train Operating Companies. June 2009. p. 21. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ "BBC NEWS - England - Operators call for new rail lines". BBC News. 15 June 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ^ Squires 2008, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Squires 2008, p. 123.

- ^ Squires 2008, p. 137.

- ^ Squires 2008, p. 139.

- ^ Nicholson 2006, p. 65.

- ^ The Shrewsbury and Newport Canals Trust

- ^ "Trust news report, quoting Inland Waterways Association annual report 2006". Shrewsbury & Newport Canals Trust. Archived from the original on 30 June 2007. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ "Inland waterway restoration & development projects in England, Wales & Scotland" (PDF). IWAAC. 2006. p. 43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ "Shropshire Canal". Shropshire History. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ "Hay Inclined Plane - Description". The Transport Trust. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

Bibliography

- Awdry, Christopher (1990). Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies. London: Guild Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85260-049-5.

- Casserley, H C (April 1968). Britain's Joint Lines. Shepperton: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0024-7.

- Hadfield, Charles (1985). The Canals of The West Midlands (3rd ed.). Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-8644-6.

- Nicholson (2006). Nicholson Guides Vol 4: Four Counties and the Welsh Canals. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-721112-8.

- Rolt, L. T. C. (1970). The Inland Waterways of England (5th Impression). London: George Allen and Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-386003-8.

- Squires, Roger (2008). Britain's restored canals. Landmark Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84306-331-5.